by C.J.

Revolutionary Worker #1271, March 20, 2005, posted at rwor.org

In the autobiography Ossie Davis wrote with his wife Ruby Dee, he tells a story about living in Waycross, Georgia. He was 6 or 7; it was around 1925.

"I was on my way home from school when two policemen called out to me from their car, ’Come here, boy. Come over here.’ They told me to get in the car, I got in, and they carried me down to the precinct. They kept me there for about an hour.. Later, in joshing around, one of them reached for a jar of cane syrup and poured it over my head. They laughed as if this was the funniest thing in the world, and I laughed, too. Then the joke was over, the ritual complete. They gave me several hunks of peanut brittle and let me go.

"I never told Mama or Daddy. It didn’t seem all that important. They were just having some innocent fun at the expense of a little nigger boy. And yet, I knew I had been violated. Something very wrong had been done to me, something I never forgot. And why did I never tell anyone? Perhaps even then I feared that such information would force Daddy into a confrontation that he couldn’t win and might even leave him dead..."

—from With Ossie & Ruby, In This Life Together

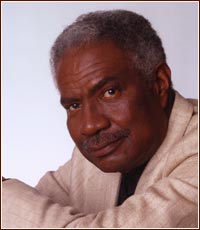

Ossie Davis—writer, actor, director, fighter for Black liberation, and public intellectual of breadth and compassion—grew up in America’s lynching belt.

You could say that Ossie’s 60 years on stage, in film, and at the frontlines of the struggle against injustice, expanded what it meant to be human in America—his unforgettable voice a kind of basso profundo for the aspirations of Black people to get free; his avuncular smile the outward projection of an inner toughness. When he died in February 2005 at the age of 87, it was a shock and a great loss to literally millions around the world.

Ossie described his father: "He couldn’t write his name, [but] he could build a railroad line from scratch, which in that day and age was considered a white man’s job." For this, the KKK threatened to shoot him "like a dog," to which Kince Davis replied, "Come right ahead, but you better shoot straight." He later became an herbalist and country healer, providing the only medical care available to many Black people in Georgia and Northern Florida.

"They took life and broke it up in pieces and fed it to us like little birds," Ossie said of his parents. He knew early on that he wanted his own life to be about telling the world the stories of such people in a way that reflected their strength and humor and courage.

In high school, Ossie studied the famous Black leaders,—the fiery abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture, and the moderate educator Booker T. Washington, and he "picked up Shakespeare for fun." He was the first child in his family to go to college. In 1935, he hitchhiked to Washington DC with $10 pinned to his shirt and enrolled in Howard University, where he would do most of his learning not in the classroom but in "bull sessions" that went on continuously in the dorms and study halls:

"In the South we mumbled our discontent to one another, clucked our teeth, and went on about our business. We tended to end such discussions in prayer, leaving the dirty work to be done by the Lord, but here the appeal was to our unaided intelligence. Howard University students not only took themselves quite seriously but Washington DC, with its Jim Crow laws and arrangements, was a particular insult to them. They were angry, hostile, and openly contemptuous of their ’racist oppressors.’ They not only spoke out quite loudly, but also seemed prepared—never mind Jesus—for a coming vengeance of their own!"

In 1939, the internationally esteemed Black opera singer Marian Anderson was prevented from singing at Constitution Hall by the management (the Daughters of the American Revolution) under a strict segregation policy. In defiance, Anderson did a concert at the Lincoln Memorial for 75,000 people. Ossie was in that crowd: "I understood fully for the first time, the importance of black song, black music, black arts. I was handed my spiritual assignment that night."

But how to enter that world?

".Dr. Alain Leroy Locke who was my professor and head of the philosophy department, black Rhodes scholar, asked me into his office one day to find out what I wanted to do with myself. When I told him I wanted to write plays, he was astounded. Have you ever been in a theater? I said oh, yes, Saturday nights we’d go to see the cowboy pictures. He said no, no, I mean a stage with live people upon it. I said no sir. You want to write for the theater and you’ve never even been in one?. When I finished Howard he said, go to New York. Go to Harlem. There’s a little group called the Rose McClendon players. Find that group. Ask them to let you join. If they will, do everything you possibly can. Then you will learn about the theater."

—from an unpublished interview with Ossie Davis by filmmaker St. Clair Bourne

The Rose McClendon players had one rule: they would only produce plays written by, about, and for Black people. The troupe became Ossie’s family, the theater his laboratory, and Harlem his adopted home.

Ossie: "Harlem was—in ugly fact—a ghetto; a teeming black pressure-cooker surrounded by two rivers, jammed in between the devil and the deep blue sea, encircled by white power at every turn. But when we set out to see what we could see, we didn’t see prison, we saw paradise. Harlem, barely thirty years old, was the new black Rome of the African Diaspora; it was a showcase for all the talents that made us powerful."

There was Micheaux’s legendary bookstore on 125th and 7th Avenue ("said to house every book ever written by and about black folks"), Father Divine’s food commissary "with pageantry," and most glorious, by Ossie’s lights: "Harlem had many churches, to be sure; but our most important religious institution, in my opinion, wasn’t called a church—it was called the Apollo Theater. [It] was our conjure, our mojo, our voodoo, our Negro empowerment zone. our black magic, in whose hallowed confines we could overcome all enemies, even white folks. Where every week, we proved to ourselves and to the world that we had something the rest of the world didn’t have, and was not only hungry for, but desperately in need of—our music!"

World War 2 interrupted Ossie’s journey into the theater. He was stationed as a medic in Liberia in an Army which was also fully segregated, right down to the African prostitutes—women from certain villages were only for the white soldiers and women from other villages were only for the Black soldiers.

Ossie returned from the war and soon appeared on Broadway, starring in the short-lived Jeb, a play about a Black soldier who loses a leg in the war and returns home to the South and same old shit, intensified.

Ossie: "We knew that every time we got a job and every time we were onstage, America was looking to make judgments about all black folks on the basis of how you looked, how you sounded, how you carried yourself." What Ossie said of the great actor Paul Robeson was also true of himself at that time: "What was the assignment of the black actors who came along when he did? We had to present a face of our people in an effort to reinstate our dignity and to establish an identity that said to the world, we are human beings."

To get a sense of the racist sludge Black actors had to wade through in the 1940s, consider this commentary in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin that was intended as a positive review of Jeb : "Negroes.as usual demonstrate the natural and remarkable histrionic talents of this race upon the stage. They seem instinctively to grasp the meaning of their part and give it an uninhibited projection. That the emotions called for are primary, need not detract from the performance."

Ossie met the actress and Harlem native Ruby Dee on stage in Jeb, an encounter which launched their lifelong collaboration as artists and soulmates. They starred together in innumerable plays and films, including the pathbreaking A Raisin in the Sun, which Ossie called "a landmark, a delicious bombshell"—the first play to reach Broadway by a Black woman playwright, Lorraine Hansberry.

Ossie, who had never intended to be an actor, would eventually appear in over 30 stage plays ( Anna Lucasta, Green Pastures, I’m Not Rappaport.), 40 films ( The Cardinal, The Hill, Slaves, Countdown at Kusini, School Daze, Do The Right Thing, Jungle Fever, Grumpy Old Men.) and in several TV series ( Roots, B.L Stryker, Evening Shade...) to name only a few.

Roger Guenveur Smith, the actor who played Smiley, the stutterer in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, spoke to the RW about his experiences with Ossie:

"He was always ready to go, which was a tremendous example to come from an actor of any age, but especially from someone who was working well into his 80s. I don’t think he ever phoned in a performance in his life... His character in Jungle Fever was just full of contradictions—the Bible come to life in a really disturbing modern way. The character in Do The Right Thing, Da Mayor, was extraordinary, and a lot of it was improvised."

In St. Clair Bourne’s documentary, The Making of ’Do The Right Thing’, Ossie talked about Da Mayor, the endearing and observant neighborhood drunk:

"I approached him from my own memories, growing up as I did in a small Southern town watching old black men, some of them too old to work, some too sick to work and some just unemployed. Every day they would be sitting at the railroad station and they would wait for the train to come. They would comment on the train as it came in, they would comment on it as it stood there, and they would comment on it as it left—as if they controlled the train, as if they made it happen. I knew powerlessness from that. I knew the pain of it, the joy of it. I knew the jokes that they told. But more than that, I knew what they were covering up."

Ossie acted in several of Spike’s films, and in this way was introduced to a whole new generation of fans. Roger: "He was a gifted writer, some of the best speeches he delivered in Get On the Bus were his own. That he would conjure up this whole story of why Jeremiah would go to DC [for the Million Man March] was extraordinary. I think people need to revisit that film for the stamp of authenticity he put on it. When I brought out my guitar on the side of the road to do the ’Shabulla’ roll call, he was ready to get it on. It was beautiful to see this man working the blues tradition inside the hip hop thing we had going on. He was exceedingly well spoken and conscious of the effect of words but he had no problem as an artist going to silence and allowing silent moments to play as effectively as words."

Ossie never stopped writing throughout his life, often typing away backstage or between takes on a film shoot. Possibly his most enduring work, Purlie Victorious, played on Broadway in 1961 and later became a musical, Purlie,and a film, Gone Are the Days. (There are plans to remount Purlie in New York City this spring.)

Purlie is the story of a "new-fangled preacher-man" from Waycross singing a fresh tune: "Ain’t gonna promise no pie in the sky / Life ever after right after you die/ I got a different banner to wave/ How ’bout some happiness this side of the grave?" Purlie leads his fellow sharecroppers into a sly caper to redistribute some wealth and power away from Ol Cap’n, the white overlord. But the piece is not what one might expect, and actually not what Ossie expected either, at first. He said it started out as an angry play, but "the meaner I made the white folks, the more they became, not humans, but caricatures. And even worse, my Negro characters, too lost their humanity. I wanted my play to bring the South to judgment.to find it guilty as charged of every crime committed against me and my people, then punish it. But no matter how angry it made me, I couldn’t read what they were doing to the superinnocent little black boy without laughing out loud!"

He transformed the play into a raucous pull-no-punches comedy—jabbing mercilessly at the local Uncle Tom, and ridiculing the arrogantly ignorant Ol Cap’n to death (literally—"the first man in this world to drop dead standing up").

It was typical of the gravitas and humor flowing from a strategic confidence in the people that Ossie brought to everything.

How to take the full measure of Ossie Davis? You could start on the cold morning in February 2005 when thousands of Black people patiently filled up block after block around New York City’s Riverside Church, hoping for a chance to say good-bye. In the lines were actors who had found their voice through hearing his, mothers bringing small children to witness history, folks on canes and walkers determined to honor a dear friend who had been a part of their lives for decades. The thousands included Cornel West, Tavis Smiley, Wynton Marsalis, Spike Lee, Bill Clinton, David Dinkins, Maya Angelou, Harry Belafonte, Malcolm X’s daughter Attallah Shabazz, Avery Brooks, Alan Alda, Sonia Sanchez and countless others who had shared in Ossie’s wide-ranging artistic and political life.

Even after it became clear that the cavernous church could hold no more, the crowds remained outside for hours as a dozen African drummers took up a vigil on the sidewalk and the limousine drivers turned up their radios so that people could hear the broadcast of the proceedings inside.

At the service, actor Burt Reynolds, who grew up in the same town as Ossie and later co-starred with him on the TV series Evening Shade, said, "As I grew to love Ossie, he took the bad part of the South out of me."

RWwriter Sunsara Taylor commented on her blog: "It says as much that Ossie could do this as it does that he would do this. He neither dismissed people narrowly, nor shut up and accepted the injustices which surrounded him."

Ossie charted a brave course. He stuck his neck out on controversial matters, and he lent support to people who were more underfire, even when he didn’t fully agree with them. He had a sense of the big questions facing humanity and a non-sectarian understanding for when uniting was a life and death matter for the oppressed.

He was influenced by the widely embraced Marxist currents of the ’40s: "We young ones in the theater, trying to fathom even as we followed, were pulled this way and that, by the swirling currents of these new dimensions of the Struggle, which split us down the middle. Black revolutionaries fighting, just like the Russians, to liberate the workers and save the world, against the black bourgeoisie fighting, at the behest of white folks, to defeat the Communist menace and save the world. I, for one, had no trouble identifying which side I was on. I was on the side with [the revolutionaries] Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois. We wanted leaders who knew about revolution, the class war, and the dictatorship of the proletariat to take charge of the Struggle." Ossie described himself as part of a "semicadre of mostly black actors, singers and dancers who saw ourselves as revolutionaries, too, and followed in Robeson’s wake whenever we could."

Ossie’s mentor, Paul Robeson, was a Black actor, singer, and intellectual of enormous power who broke open new ground in the arts in the ’40s, becoming intensely popular in America and across the world. Robeson was the target of vicious attacks by the U.S. government in the ’50s. As the U.S. threatened war against the Soviet Union, Robeson refused to back off his support for the Soviet Union (which at that time was still a socialist country). J. Edgar Hoover called him the most dangerous Black man alive.

Ossie never abandoned Robeson. As the witch hunt led by Senator McCarthy targeted any artist remotely associated with liberal or left causes, many were driven off the stage and out of the movies and concert halls.

Ossie set out his view of the situation in an interview with St. Clair Bourne:

".At the beginning of the blacklist, the artistic community which had been so vocal on the subject of [racism] and.the atom bomb—this community, particularly Broadway, was in the forefront of what to do to make this world a better place. But the powers that be were able to turn that around. And one by one, the people in Hollywood began to back away.

"The question in Hollywood was, were you or were you not a communist. And if you said you were and you wanted to get out of it, [they said] ’give us names of other people you know to have been communist.’.A lot of actors in Hollywood left Hollywood rather than answer that question. But a lot in Hollywood began to answer that question. We on Broadway looked a bit down on Hollywood on that issue. We still knew how to organize, we still knew how to protest, we still knew how to hold meetings and rallies in defense of what we thought were principles and all of that.

"On one occasion when I rose in an Equity meeting and made a motion that Equity should support Paul Robeson in his fight to get his passport back, there was pandemonium in the meeting. Now why was there pandemonium? The pandemonium was simply this—to those in the meeting who raised their hands in support of Robeson getting his passport back, their names went on a list. And before long, you would get a call.

"Since black folks didn’t work too much in Hollywood, they couldn’t get us so much on who we knew. But the question for us was, do you know Paul Robeson—have you been duped by Paul Robeson? And the way out of course was to say yes, I was duped by Paul Robeson. Some of us went that way. A lot of us didn’t. Ruby and I of course chose not to. And we were investigated, subpoenaed and I’m sure there must have been some job opportunities that we lost but you never know. Because nobody writes and tells you—’we had a job for you but we blacklisted you.’ Also at the same time, Ruby and I said well, we don’t know whether we’re unemployed for being red or being black. Even if we hadn’t said anything about Paul Robeson, there weren’t that many jobs out there for us. But yes, we were investigated. We just took it as a part of the struggle we were engaged in."

To survive those dark days, Ossie and Ruby relied on the people they had always relied on. They did readings and performances in meeting halls and churches throughout the communities of the oppressed. These were mainly Black gatherings, but they also had many ties with Jewish communities and in the trade unions.

The blacklisted ’50s were not the only lean years for Ossie and Ruby; they stood on principle throughout their career, and paid for it. But, as filmmaker St. Claire Bourne told the RW :

"Even when Ossie was on Broadway or in Hollywood, he still continued to pay attention to those small institutions - you could go to a party in the deep bowels of Bed-Stuy, and he and Ruby would be there. That was his base, and he never forgot it. It was also the source of his artistic strength, because you could observe stuff about people that you couldn’t in the great white world. The thing that amazed me about Ossie is he kept on point all the time. When it was time to fight, he did that, and he did it in the company of political allies, and on the stage. And he did it articulately so in listening to him, you learned something at the same time. He was very sensitive to people’s feelings, he could tell the truth without being crude."

At the funeral, Hasna Muhammed, one of Ossie’s grown daughters, in describing life in the Davis household, offered another angle on who Ossie was. She spoke directly to the audience, to Ossie’s "public": "He talked about you and we would make room for you at our dinner table. And we couldn’t just say ’Pass the peas,’ and listen. He had us working. ’Who will take the place of Lorraine Hansberry?’ ’Can you figure out a way to eliminate poverty?’ We kids had to answer one by one.and not infrequently we found our words in his mouth when he was out there with you."

Friends and colleagues cannot talk about Ossie without speaking of Ruby, and they reserve a special tenderness to describe what Ossie and Ruby had together. They were an uncommon example of a man and woman who for over five decades were able to grow and strengthen each other to move through the world as equals—always looking for the best, and the new in one another. Life stories like theirs are rare in a society where patriarchy and the cash nexus intrude into every relationship.

Ruby was already an accomplished actor when Ossie met her; she would also become a noted writer and producer. Ossie had the intelligence and humility to admire and draw from her strengths. As he put it in one joint radio interview: "I was stimulated and inspired greatly by her sense of adventurousness." Ruby was no-nonsense about their thing: "We are not a fairy tale couple—far from it; rather we have clawed our way to some clarities and satisfaction by dint of trial and error. We were lucky enough to be born into the Struggle and from that we have achieved some sense of our worth as married people, lovers, and friends."

St. Clair Bourne told the RW : "I know one thing, two Black people with a marriage like that—not that they didn’t struggle, but they were able to work together—this is unusual. See, what happens is, the culture is not geared for us. In a culture that created slavery, the image that we’re supposed to be in the eyes of the white world is not married. Ossie and Ruby represented a kind of civility without selling out. In addition to that, they created together as artists. And people like Spike used this. He said he developed characters like Da Mayor and Mother Sister in Do The Right Thing —he created those roles by looking at who they were—people who might have some fighting, but found a way to stay together. He drew from that."

On February 19, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated. Ossie was asked to give the eulogy at the funeral. He accepted. It’s hard to imagine the atmosphere of fear and state intimidation following the murder, but it says something that the funeral was held in the Faith Memorial Chapel, a small church in Harlem and the only religious institution which dared to host it.

Ossie’s eulogy captured the impact of Malcolm on generations of Black men (as well as the male-oriented leadership of the Black liberation struggle at that time):

"Malcolm came along and said, stop, stop, you are men. Stop, you do care. Stop, there is life in you. Stop, there is still the possibility that manhood, that courage, that strength, that imagination, will make the difference. It was he who rallied our flagging efforts, who taught us to stand up off of our knees, especially the black men, but also the whites, but to stand up off of our knees, to address ourselves to the truth, even if we were killed for it, and it’s been a long time since that kind of courage and bravery was abroad in our land."

Malcolm was friends with Ossie and Ruby. He visited them at their home in the days before his assassination, and they stood steadfast with him (and his family in the years since) even though Malcolm’s revolutionary nationalism did not entirely match their own views.

Ossie was forthright and self-critical about Malcolm, as he was about every important matter. Sometime after the funeral, he wrote: ".however much I disagreed with him, I never doubted that Malcolm X, even when he was wrong, was always the rarest thing in the world among the Negroes: a true man. And if, to protect my relations with the many good white folks who make it possible for me to earn a fairly good living in the entertainment industry, I was too chicken, too cautious, to admit that fact when he was alive, I thought at least that now, when all the white folks are safe from him at last, I could be honest with myself enough to lift my hat for one final salute to that brave, black, ironic gallantry, which was his style and hallmark, that shocking zing of fire- and-be-damned-to-you, so absolutely absent in every other Negro man I know, which brought him, too soon, to his death."

Bill Clinton, who was friends with Ossie and Ruby, attended the funeral and was invited to address the crowd. Speaking with some emotion, he said he always felt challenged by the two of them, and he finally realized why: "They were free, and they always have been." He then recited from memory Nina Simone’s "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free." There was an audible rumble in the church as those gathered sifted through the contradictions—many stacking up the former U.S. president who could feel at home with this crowd against the current pre-Enlightenment Christian fascist in the White House.

When Clinton said, "I think Ossie Davis would have made a good president," a roar of affirmation went up, and I was struck by two things: Clinton’s envy of Ossie and the irony of the moment. Ossie and Bill may have been friends, but you could not be who Ossie Davis was and be president—not of this rapacious empire. Clinton’s tenure had proven this in spades. The unprecedented number of young Black men jailed and the intensifying police murder on his watch was only one measure of how the oppression of Black people has scarce been eliminated, and has taken barbaric new forms.

Ossie’s life embraced the wide range of attempts by the oppressed to confront these contradictions over the past 60 years. He did not stop seeking. And the sense of loss you could feel among those who gathered to remember him reflected an unbearable gap between what exists in the world and what needs to happen.

Well into his 80s, Ossie was always looking forward—towards the next generation, the next liberating struggle, the next creative innovator who might connect him to the new and arising.

In the ’90s, he helped inspire the new generation to take up the fight to stop the execution of political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. In 2003, he lent his weight and voice to the historic Not In Our Name Statement of Conscience, a manifesto signed by many of America’s noted artists and intellectuals opposing the war in Iraq and the repression at home. (His reading of the statement can be heard at www.nion.us) He turned up to speak at every major rally against the Iraq war, and his sympathetic and commanding presence could be found in many other struggles—supporting prisoners’ rights, opposing the genocide in Darfor, standing with those fighting police brutality.

He consistently and creatively worked to carve out more space in society for the work of artists telling the truth. At an evening for the National Day of Art for Mumia Abu-Jamal at New York’s Public Theater in 1999, he spoke of the importance of valuing the brave individuals who provide stages for a culture of resistance to be seen and heard. He talked about the necessity for artists to stand with the oppressed, while acknowledging how difficult it can be for artists who are in the public eye but who are not, after all, politicians or trained public speakers.

And Ossie never stopped creating. The day before he died, they say he was rehearsing a dance number on the set of a film in Miami. His response to people who asked him how he kept "doing it, doing it": "It beats pickin’ cotton."

In possibly the last broadcast interview, with Tavis Smiley, Ossie said:

"The gift that we had was that there was a vision set before us and our people that we could see and understand and participate in. We had a focus from the time we stepped on stage up until this very day.. We can’t float through life, we can’t be incidental or accidental. We must fix our gaze on a guiding star as soon as one comes upon the horizon. And once we have attached ourselves to that star we must keep our eyes on it and our hands on the plow. It is the consistency of the pursuit of the highest possible vision that you can find in front of you that gives you the constancy, that gives you the encouragement, that gives you the way to understand where you are and why it’s important for you to do what you can do."

In short, you could count on Ossie Davis to try his best to do the right thing and ask us to do the same.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Much appreciation to Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee for their extraordinary autobiography, With Ossie & Ruby, In This Life Together, and to St. Clair Bourne for his interview with Ossie (conducted in connection with the making of his documentary Paul Robeson: Here I Stand ). Thanks also to St. Clair and to Roger Guenveur Smith for sharing their insights and remembrances of Ossie with the RW.