In the Bitter Aftermath of the Trayvon Martin Verdict

The Outrages of AmeriKKKa... and the Need for Revolution

Interview with Carl Dix

Updated September 23, 2013 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Carl Dix is a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party and one of the initiators of the October 22nd Coalition to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation. He was recently interviewed by Revolution/revcom.us correspondent Sunsara Taylor on a range of questions relating to the movement to stop mass incarceration, the fight to stop the slow genocide against Black people, and how to do all of this as part of building a movement for real revolution to get rid of this system at the soonest possible time and to bring into being a far better world. The following is the transcript of the interview. The audio is also available at revcom.us.

Sunsara Taylor: Hi, my name is Sunsara Taylor and I'm here with Revolution newspaper, revcom.us, sitting down with Carl Dix to get into a number of things. Carl Dix is someone who has deep roots in the struggle for revolution and the emancipation of humanity, he's somebody who came of age in the 1960s, was drafted to go to Vietnam and did a righteous and heroic thing, he refused to serve in Vietnam. He served two years in Leavenworth military prison for refusing to go out and carry out war crimes. And as soon as he got out of prison he actually dove deeper into the struggle, got connected up with the movement for Black liberation and through that connected up much more deeply and became a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party.

Since that time he has never turned back and it would take a long time to get into everything that he has done. But most recently he has been making headlines and making waves for spearheading a movement to stop mass incarceration, to stop the slow genocide of mass incarceration, to lead a movement of civil disobedience against stop-and-frisk as part of that. And to do all of this as part of building a movement for real revolution to get rid of this system at the soonest possible time and to bring into being a far better world. It's a great pleasure and a great honor to sit down with you Carl, thanks for joining me.

Carl Dix: Well, I'm really glad for the opportunity to do this interview and get into the important discussion of the important questions that we're gonna do today.

Taylor: Ok, so there's a lot of things that I want to cover that I think our readers and listeners will want to hear about, from the recent developments this summer around the massive outpourings against the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, the stuff around the heroic hunger strike of prisoners in California against solitary confinement and torture in the prisons; elements of building the movement for revolution, the campaign to get BA—Bob Avakian, the leader of this revolution—known throughout society; the upcoming major day of protest, which really needs to be, and I know you're burning to talk about this too, a major day of struggle—October 22, a national day of protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression, and the Criminalization of a Generation. And so there's a number of things, but first, I just want to take you back and I want to ask you, on the day that the verdict came down, on the day that George Zimmerman was acquitted for the murder of Trayvon Martin, how did you feel?

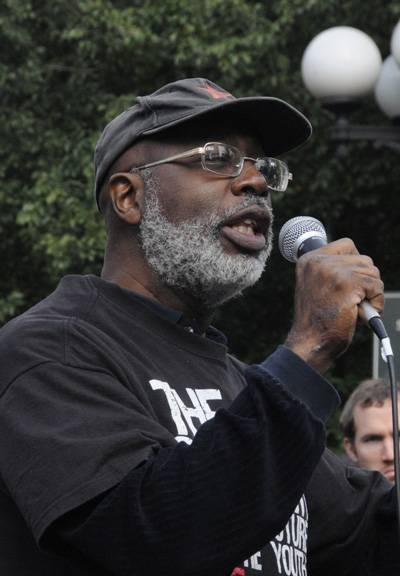

Carl Dix. Photo: Li Onesto/Revolution

Dix: I guess on the day, it felt like a kick in the gut. You know, like here it is, 2013—60 years after the lynching of Emmett Till by a couple of white men who decided that this 14-year-old Black kid had gotten out of his place and beat him viciously and killed him and then threw his body into the river. And when it was found out that they did this, they got put on trial and let walk free. And then days after getting out of court they sold their story to Look magazine, talking about how they had murdered Emmett Till, but were able to walk away from that. And then it took me back to even before the Civil War in this country, back to the Dred Scott Decision, which was a decision that the U.S. Supreme Court made, I think it was in 1857, in the case of this Black man who had escaped from slavery and was brought back into court by his former owner and in this case the Supreme Court literally said that Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect.

And then we're up to 2013 and we have a situation where this wannabe-cop vigilante sees a Black youth, walking, talking on the telephone, with iced tea and Skittles, decides he's a criminal, stalks him, confronts him and shoots him dead. And then the system says, no crime committed here. They were saying again, more than 150 years after the Dred Scott Decision, that Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect. And that's how that made me feel at that point, you know.

Now the day after, I was heartened. I was heartened by the fact that large numbers of people all across the country responded in outrage to that verdict. It was Black people, it was Latinos, it was also a number of white people involved in this. People out in Los Angeles marched onto the highway, Interstate 10, and stopped it, blocked it, that's how mad they were. They went out on that highway and they were gonna show—no, no more of this, we can't take this. New York City, people in the thousands marched into Times Square and shut it down. And then in cities all across the country people were responding in similar ways.

Police all across the country brutalize and even murder Black and Latino youth and almost always get away with it. The standard approach of law enforcement is to treat Black and brown youth like they're guilty until proven innocent.... They're treated like a class of permanent suspects. And this verdict in the Trayvon Martin case brought all of that together for people. And that's why people were up against this thing of what does this say about America, why does this happen again and again? And do I want to be a part of this society where this can happen and then the system says it's OK.

And to look at and listen to what people had to say at these, you saw Black parents there with their children in tears, hugging them and saying, how can I tell my children about this and what does this mean for them and what does it mean for us? That this vigilante can murder a Black youth and get away? What are they telling us? What are they telling us about the nature of America? What does this mean? There were a lot of people speaking like that, speaking in tears about it. There were white people who came out to it and who said, look, I do not want to be a part of an America that says that it's OK to do that. These were people who had like, kind of been forced to look at some very big questions, questions about the nature of this society, the nature of America. Questions about why do these things happen again and again and again. Because a big part of the reason why this hit people this way was both the stark horror of what happened to Trayvon, but the fact that things like this happen again and again in this society.

Police all across the country brutalize and even murder Black and Latino youth and almost always get away with it. The standard approach of law enforcement is to treat Black and brown youth like they're guilty until proven innocent, if they can survive to prove their innocence. And in many, many cases, our youth don't survive to prove they're innocent. They're treated like a class of permanent suspects. And this verdict in this case brought all of that together for people. And that's why people were up against this thing of what does this say about America, why does this happen again and again? And do I want to be a part of this society where this can happen and then the system says it's OK.

After the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, large numbers of people all across the country responded in outrage to that verdict. It was Black people, it was Latinos, it was also a number of white people. In New York City, people in the thousands marched into Times Square and shut it down. Photo: AP

And see this is very, very important because when people are grappling with these kinds of questions is when we can make the biggest advances and make leaps in bringing to people the way out of this mess, because things don't have to be this way. We don't have to continually watch parents burying children who have been murdered by the police and their caught murderers walk the streets scot-free, still with a badge and a gun, and in position to maybe brutalize or murder somebody else's kids. We don't have to continue to face outrages like this or the many, many other horrors that come down on people because of this system—the violence against women, the wars for empire, the drone strikes, the massive government spying, the way the very environment of the planet is being ravaged.

All of this could be ended through revolution, communist revolution. This is not only needed, but it's possible. And there's leadership for this revolution in Bob Avakian, the leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party and the new understanding or new synthesis of communism that he's brought forward. So this is a time when we need to be really accelerating our efforts to bring to people that things don't have to be this way, that this horrible world could be transformed through revolution and nothing less than that and to bring to people the leadership that we have for this revolution and also the plan and strategy that the Revolutionary Communist Party has developed for making this revolution and the vision of the kind of society that could be brought into being after the revolution. And all of these things are things that people need to get into, we need to be bringing to people. And people need to be going to the website, revcom.us, and looking up these things and digging into them and engaging them.

Taylor: Well, a minute ago, you said a lot of people, all kinds of people, but you mentioned white people in particular, were asking in the wake of this verdict, what kind of a country is this? What is it about America? And then after that happened then Obama got out, he gave his statement about what it's like to be a Black man in America, being profiled, of being, you know, women clutching their purses, all this sort of thing. A lot of people were speaking to—well, you know, yeah, this country has some problems, but it's on a trajectory, these problems are being improved, they're being worked on, we're advancing, we still have a long ways to go, but we've come a long ways. And so what would you say to people who were asking that question? Because on one the one hand, you do have the things that you're describing. You have the mass incarceration. I want to talk more about that as we go forward. We have the police brutality. You have the things that you're describing. But you also have a Black president. I think this is confusing to people so maybe you could cut through some of that.

Mass incarceration is like a slow genocide that could easily become a fast one. Because look, what genocide is, it's not only what happened in Nazi Germany. Because a lot of people understand genocide is when they start lining people up against the wall and start shooting them or gassing them in the ovens. And that was the last stage of the genocide in Nazi Germany. But there's a process to get to that. There's a process of identifying a grouping of people, demonizing them, segregating them. See and these are all things that have already happened in this country.

Dix: OK, that's actually a very good question because if you look at the situation today you do have opportunities for sections of Black people. Things have opened up, Black people have gotten into positions of influence, gotten into college, off of that gotten into professions, and you know political positions, including we got a Black president today. So that is a part of the reality. But then we also have to look at that as that has happened and as that is developing we also have a situation where for millions and millions of people in the inner cities of this country and especially very intensely for the youth there is no future in this society and in this system. And this is not the fault of the people in the inner cities, that they don't work hard enough, that the parents don't make the kids do enough homework, that the young men don't pull their pants up or that the young women are having babies out of wedlock—which is all too often the way this stuff gets discussed. It is the result of the very way this system operates, this capitalist-imperialist system operates.

Because you had a situation when Black people migrated from the rural South, from the plantations, they migrated into the cities and became part of the workforce in the factories, the bottom tier of the workforce, working the hardest, lowest paying, most dangerous jobs, but they were in part of that workforce. And people were looking towards, well, does this mean we can continue to go farther and advance. And while a few did, what actually happened is, with globalization, the internationalization of production, you saw a lot of those factories being moved out of the inner cities and then moved out of the United States to halfway around the world, to places where they could find somebody who they could make work those jobs for much less pay, in much more dangerous conditions. And through that increase the profits of the handful of capitalists who owned and controlled those factories. But that left millions and millions of Black people and later joined by millions and millions of Latinos in the inner cities, growing up facing futures of hopelessness.

The ways in which to survive and raise families had been sucked out of the ghettos and barrios across the country. The educational system in the inner cities had been wrecked and geared towards failing the youth. And that has a lot of young people growing up facing what choices for the future? You could look for a minimum wage job, but with the way the economy has developed and a lot of people who had more stable jobs being knocked down and being brought into the workforce on a lower level, those minimum wage jobs aren't even there for everybody. So then you're left with, do I join the military and become a killing machine for this system in some of the wars for empire that it's waging around the world? Or do I find some hustle to survive, legal or illegal? And you do have a lot of our youth who are into crime and drugs, who are fighting each other and even killing each other.

But all of this has developed because of the very operation of the capitalist system, together with conscious policies that the people who run the system have taken, policies that have emphasized and brought forward wars on crime, wars on drugs, which are fundamentally wars on poor people, on Black people and on Latinos. And that's where we have the mass incarceration that has more than two million people warehoused in prisons across the country. A lot of them are in there for drugs and you know just drug possession. That's what we have, we have a lot of people who are in that situation—people who when they get out of prison find it even harder to find work, aren't allowed to get government loans, they're banned from getting government loans so they can't go back to school or start a business or anything like that. They're not even allowed to live in public housing and in many states they can't even vote. So you're in a trajectory where it's even harder to make it after you've been in prison.

And that's what millions and millions of people in the inner cities are directly facing and then millions more are tied to people who are facing that. Because when you send a man or a woman into prison you actually take the hearts and the lives of their loved ones are caught up in that incarceration thing too.

So that's what we're dealing with and that's the backdrop to it, the actual operation of this system and the conscious policies that the ruling class has adopted in relation to the contradictions that it faces from the operation of the system. And yes it has provided some opportunities and then it uses those people who do make gains and get positions in order to help keep those who are being ground down by the system in line. And we see that at its height with Obama. That's why Bob Avakian called him a trump card for the imperialist rulers because he can come out and say, "OK, it's bad and I know it's bad and I've experienced some of it too, I've been followed in a store and this kind of stuff. But you got people like me who are in positions now, in positions of power and influence and we can work on this and we can continually make it better. So that's the way we should go at it." And they're working to try to keep people having faith in the system.

The problem that they got is the reality though. The reality of a verdict like the Trayvon verdict where you have the system saying you got no rights in this setup. And that's what they're trying to do, they're trying to take the people who have been jolted by that and bring them back into the fold, through using Obama, through using Eric Holder, the Attorney General—that makes him the head law enforcement person in the country—and having him come out and make some statements. But that's what they're actually doing, they're trying to work to get people who are losing faith in the system, questioning the system and trying to get them to come back in, to give the system another try.

Taylor: OK, so, I mean they're using Obama, but Obama is also very consciously part of this.

Dix: Oh yeah, he's like the president, it's not like he is someone who is being taken in or against his will forced to... he's the commander-in-chief of the U.S. global empire and is working to keep that empire in effect, including here in this country, keeping that empire and its domination and the people in the country drawn into the framework of the system.

Taylor: So, let me ask you this, when we began you went through the history of this country, from slavery to Jim Crow to today with the new Jim Crow. And one of the things that you've been emphasizing a lot is that we are now confronting, which you spoke to some just now, the whole epidemic of mass incarceration which is grinding up millions and millions and millions of lives. And it's the snatching of the youth, it's the stealing of people's fathers, it's the hugest rate of women incarcerated anywhere in the world and then it's all the networks who are connected to that, predominantly Black and Latino, but all the networks connected to them. And then the conditions in prison too, which maybe you want to speak to. Because a lot of people who've been through it don't really want to go there and talk about it. And a lot of people who haven't been through it they just don't know anything about what actually goes on in these prisons. But you've described all this as a slow genocide. And I think it'd be helpful if you would talk about it. I don't get the impression you say that just for rhetorical flourish. I mean, you mean that. And I think it's a true statement that we're facing a slow genocide. Why is that true? And what does that actually mean, what is the conditions of that for people to understand?

Dix: Yeah, actually that's a very good question because look, we revolutionary communists, we try to speak to what is the objective reality, what is true. Not what can we say to hype people up and get 'em to do what we might want them to do. We have to actually bring to them what the reality is and to help them understand that reality and how it's being driven. But also, how we can transform that reality. And that's why we developed this understanding, that's how we came, let's look at this thing of mass incarceration. What is it, why does it happen, what's driving it and where is it headed unless we stop it in the only way that's really possible, through making revolution? And that's where we came to the understanding that mass incarceration is like a slow genocide that could easily become a fast one.

Because look, what genocide is, it's not only what happened in Nazi Germany. Because a lot of people understand genocide is when they start lining people up against the wall and start shooting them or gassing them in the ovens. And that was the last stage of the genocide in Nazi Germany. But there's a process to get to that. There's a process of identifying a grouping of people, demonizing them, segregating them. See, and these are all things that have already happened in this country. And that's part of the process that we're going through. And then when you take hundreds of thousands of people from a particular group, you warehouse them in prison. Then when they get out they're treated like second class citizens and have little to no opportunity to survive and have a decent life. And the actual definition of genocide, internationally, from the United Nations is putting a grouping of people in whole or in part in conditions that make it impossible for them to survive and thrive as a people. And that's actually what's happening with Blacks and Latinos throughout the inner cities of this country.

Sections of a whole people who are being put in a situation that make it impossible for them to survive and thrive. And that's what we're dealing with. And why do we say that it's a slow genocide? Well, because it's not yet at the point where people are being put up against the wall and shot, massively. Although a lot of people are being shot down by the enforcers, the police, the Immigration and Naturalization Services, INS, La Migra is gunning people down. So this is happening. But it's not happening on a massive scale yet. But it could easily change.

I mean just in the last few days, this Tea Party senator, Ted Cruz from Texas, went to a commemoration of Jesse Helms, a former senator from North Carolina, and he made this statement repeating something that was said a few decades ago by John Wayne, that we need a hundred Jesse Helms, meaning that we need a whole Senate of Jesse Helms. Well, Jesse Helms was a racist, woman-hating, gay-hating, reactionary, fascist-type force who was in the Senate for decades. I mean, this man, I don't know that he was in the Ku Klux Klan, but the only thing he was missing was the hood because he had all of the political positions and the outlook that the Klan stood for—the vicious suppression of Black people, the subjugation of women to subordinate places in society, and to getting rid of gay people. He stood for all of that and he acted on that in Congress throughout his career in there. And to say today that today we need 100 Jesse Helms is to say that we need to go back to that, we need to accelerate the reactionary moves that are coming down, the fascistic moves that are coming down, and that's where things need to go. And things are in fact going that way. We can't ignore the actual steps toward that.

You know, the U.S. Supreme Court took up some cases. They took up a case on affirmative action and you know, cut the legs out of that. They took up a case on the Voting Rights Act from the 1960s that made it possible for Black people in the southeastern U.S. to gain the right to vote back in the 1960s. The Supreme Court gutted the heart out of one section of the Voting Rights Act, which was the key section that allowed people to vote because it took the ability to determine whether laws could be passed and restrictions made on people's right to vote out of the states that were restricting people's right to vote. Well, the Supreme Court said we don't need to do that any more—that was then, this is now. Within days, states across the country had begun to pass restriction after restriction on the right to vote—and restrictions that openly were targeting Black people and Latinos.

So there is a powerful move to take things back in that direction and to institute very horrific, fascistic moves. And that's why I say we're talking about a slow genocide that could easily become a fast one. And again, this isn't just because some reactionary fools have gotten close to the seat of power. It has to do with the very way that the capitalist-imperialist system is operating and in particular what I was talking about before, in the inner cities millions and millions of youth facing futures in this system where there's no hope for the future—lack of ways to survive and raise families, educational system geared to fail you and that leaves a lot of the youth having to come up with some hustle, legal or illegal, to survive. And they have developed mass incarceration as a way to deal with that. And that's something that, look, if that's not taken on—this could be taken in an even more—not just that it would stay as bad as it is now, which is unacceptable and horrible. But it could be rapidly taken to even worse conditions.

And that's part of what people have to be thinking about when they're grappling with the nature of this society, what is America? Why does this injustice happen again and again and again? And what can and must be done about it? Because what we're saying to people is, first off, it ain't realistic to say that things will stay like this and then we can make some surface changes for the better within it. Things are being rapidly pulled in a much worse direction. But it is possible to get out of this through revolution.

Taylor: So, we are looking about a month out, a little more than a month out to October 22, this is a, it’s a major national day, every year. October 22, it’s a National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation. What’s the significance of this? Maybe you could talk a little bit about where this came from, what is this protest? But also what’s the significance of it this year coming off the George Zimmerman verdict, coming off the recent hunger strike among prisoners in California, at a time when there’s a lot is happening in society and in the culture, raising the question of the condition and the treatment historically and today of Black people in this country and other oppressed peoples, at a time of slow genocide? What do you think we need to be understanding at this moment and doing to act on that understanding, looking towards October 22?

Dix: OK, well, this year, it’s the 18th annual National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation. And where this came from was back in the 1990s a few of us began to talk about like, look, all across the country police are brutalizing and even murdering people and getting away with it and we have to take the resistance to this to a national level and direct, develop it further. We have to bring together, you know, broad sections of people, not just those who have to deal with this all the time, but we need to bring broad sections of people into this fight against police brutality and police murder. And we have to take people whose lives have been devastated by this and actually mobilize them to come out and speak about what had happened to them, what had happened to their loved one, what it did to their family, to bring that out and make that exposure very widely known. Because what would happen is: the police would kill somebody and then this person would be demonized and the actual truth of what happened and the fact that most of the people killed by police were unarmed, not involved in criminal activity, was not something that very many people knew about. So that’s what we were moving to do back in 1996 and it was an interesting array of people, you know. Food Not Bombs, which was a—an anarchist was the guy who had organized that: the MOVE family was involved in it; National Lawyers Guild. And we got a number of family members of people who had been murdered by the police and brutalized by the police who were involved in bringing that together. And then as you trace it over the years, there have been things like involving people who were mobilizing around the killing of immigrants on the border and bringing that in. Also involving gay and lesbian groups and one very important period for that was in the late ’90s, 1998 I believe, when the police in New York had vamped on people who were holding a vigil around Matthew Shepherd, who was a gay man who was beaten to death, you know, outside a bar, out in, somewhere in the Northwest, I forget exactly where. And the NYPD was like, no, you will not be allowed to hold the vigil around this and brutalized people who did it, and then October 22 came a little bit after that and we welcomed people who had been involved in that vigil to be a part of this because this was a question of the society officially saying that this young gay man’s life was worthless, and people who wanted to express something around it did not have the right to do that. So that’s been the way that October 22 has developed and the way that it has brought together diverse kinds of people.

Wearing hoodies in Denver, April 2012. Photo: AP

And at this moment, it is very, very important that this day be marked because we’re talking about something that has continually been a part of this society. It isn’t like it’s gone away, it’s in fact intensified. And the repression has intensified and the criminalization of a generation has also intensified. We also have to bring into it and have brought into it the way in which Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians have been targeted and demonized since September 11, 2001. That’s been another important part of it; and there’s just been a recent exposure about just how widespread the spying on those sections of people have come down. And it is very important that right now, in the wake of the Trayvon verdict, when so many people, when for a lot of people had their eyes opened to the fact that this kind of criminalization goes down in society and is a widespread feature of it. And the way that for so many other people who knew about it, but the way in which the Trayvon Martin murder went down and the way that the system refused to even arrest Zimmerman for murdering Trayvon, and then when they were forced by outcry all across the country to put him on trial, put together a trial that exonerated him, moved people to stand up in outrage. Look, if you remember that outrage, whether you experienced this for the first time, or whether it’s what you’ve lived with your whole life. If you remember what you felt, if you still can’t think about that because, what the fuck, how to, what to make of something like that coming down. If you do think about it and can’t sleep at night about it, you have to act on October 22. You have to be out among the people, mobilizing to bring others to it. This has to be a day when all across the country people are taking to the streets in outrage, holding cultural events, teach-ins, and in other ways spotlighting the horrific reality of police brutality and murder, the widespread repression and the criminalization of whole generations of youth. This has got to be something that people respond to.

And then, even more than, that we have this thing: wear black on October 22 and people should do that. But we gotta add a new ingredient to it this year. This year, wear black and hoodies back up. Put your hoodies up because we gotta bring Trayvon out in a very big way in this, you know, because this actually brought to life the reality that a whole generation of youth have been just made permanent suspects in this society and can be brutalized and murdered and nothing is gonna be done to ’em. And we have to say in a loud, powerful, united voice: No More! No more will we sit back and allow this to go down. No more will this be allowed to go down without being met with determined, powerful opposition.

So we have to spread this across the country. If you’re on campus, you gotta organize something on your campus, involve the students there in it. If you live in a housing project, work to get people together around that. If you’re in a city where October 22 is already planned to happen, hook up with the people doing it and be a part of that. But if you don’t know of anybody doing anything in your city around October 22, then organize something and contact us and we’ll put you in touch with the October 22 National Office and get it all worked out. And if there’s somebody else doing something, we’ll put you together with them. But make sure that something is happening there.

And see this is very, very important from the perspective of dealing with the way in which large numbers of people were moved to ask big questions coming off of the Trayvon case: What does this mean? Black people who were saying: What does this mean for me? How do I talk to my children about this? What future can a society like this have for us? But also for white people who were saying: I don’t want to live in, I don’t want to be a part of a society, where this can go down. This is very, very significant and—look, as a revolutionary communist, I’m gonna be taking to people; and people who agree with that need to be taking to people that this happens because of the very nature of this capitalist-imperialist system; not only this horror, but the many other horrors—the vicious attacks on women in this society, the wars for empire, the drone missile strikes, the widespread government spying programs, and all the rest—that’s where all of that comes from. And we can end all these horrors—things don’t have to be this way—through revolution. We have the leadership for this revolution in Bob Avakian, the leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party and [we have] the new understanding, or synthesis, of communism that he’s developed. We’ve got a strategy and a plan for making this revolution and we got a vision for the kind of world and society that could be brought into being after the revolution.

All of this needs to be out there for people. And I’m gonna be working to bring that out to people. And people who want to dig into this and engage it should go to the website revcom.us because that strategy for revolution is there. The Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America (Draft Proposal) is there and the works of Bob Avakian are also available there. The film REVOLUTION—NOTHING LESS!, which gets deeply into all that I’ve been talking about here today and much, much, more. You can get hooked up with that there, you can also get hooked up with BAsics, which has quotations and essays from the writings of Bob Avakian. People need to check that out, people need to be engaging that, people need to be digging into it and they need to be acting, especially on that day.

Stop police brutality, repression and the criminalization of a generation. Hoodies up and wear black and no more to this official brutality and murder that this system has been bringing down and repression that this system has been bringing down on people all across the country.

Taylor: Recently prisoners in California waged a really important, inspiring hunger strike. How do you see the significance of that, both in terms of what it represents more broadly, and also in light of the fact that October 22 this year is happening in the wake of the prisoner hunger strike in California?

Dix: I’m glad you asked that question. First, let me go back to what I said about how O22 developed, because one person who played a critical role in assembling the original coalition that made October 22nd happen was Akil Al-Jundi, who was one of the leaders of the 1971 rebellion in Attica prison in New York. That was a very significant rebellion in the 1960s, and it helped to bring a lot of people from that generation, myself included, into more radical and even revolutionary resistance to the crimes of the system back then. And Akil, who passed away in 1997, played a critical role in forging the original October 22nd Coalition.

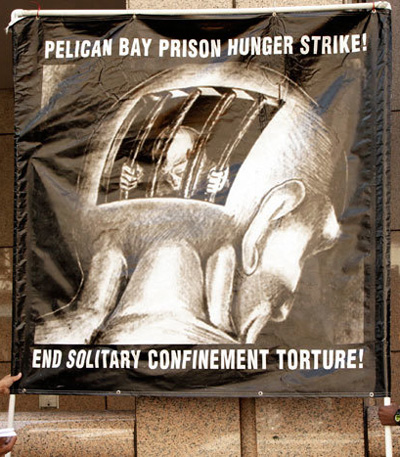

A banner at a protest in support of the prisoner hunger strikers, August 2013. Photo: Special to Revolution

And the hunger strike that prisoners launched in California on July 8 of this year was the most significant outbreak of resistance from among prisoners since the Attica rebellion. You had 30,000 prisoners in California involved at the start of that hunger strike, standing up to end conditions that amount to torture. People held in long term solitary confinement—and there are more than 80,000 people held in those conditions—are confined in small, windowless cells 22½ hours a day and longer. Many of these cells are soundproof. Some of the people are denied any human contact. People get put into these conditions arbitrarily, at the whim of a prison administrator or a guard, and there is no way to challenge being placed there. International studies have found that being held in these conditions for more than a few weeks can drive people insane—people in U.S. prisons have been held in these conditions for months, years, and even decades!

People in prison in California stood up and put their lives on the line to end this torture, and hundreds of people carried it on for two months. And leading into the hunger strike, the prisoners called for a Cessation of Hostilities—an agreement to end all fighting among the prisoners on the basis of race. This is tremendously significant because one of the ways prison authorities keep the prisoners under control is through sowing divisions in their ranks and exacerbating divisions that already exist. But these prisoners, who are condemned as the worst of the worst, are rising above those divisions based on race to stand united to fight against injustice and calling on people outside the prisons to also rise above those divisions and stand together.

Photo: AP

This hunger strike has been suspended now, but the struggle to end torture in prison continues. A lot of work was done to bring into the light of day the torture that is being inflicted on people in prison. The families of many of the prisoners spoke out; many well-known people also spoke out in support of the prisoners; an Emergency Call to End Torture in Prison—signed by hundreds of people including many prominent people—was published as an ad in the Los Angeles Times newspaper and then re-published in another newspaper in California. But still not enough people know about the horrors people are subjected to in prison or about the heroic struggle these prisoners waged against these torturous conditions. And on October 22 and in building up to October 22, work is going to be done to make many more people aware of the horrific conditions in prisons and the heroic struggle waged by the prisoners to end those conditions and the need to carry that fight forward.

Taylor: OK, so I have one more question for you which is, it's a very strategic question which is if you step back and really think about what a real revolution means, what it's really gonna take to make revolution in this country—and the amount of sentiment that began to be uncorked around the Trayvon and Zimmerman verdict but has still not been fully unleashed and how much was bound up in that—there's a real strategic question of bringing forward fighters from among those who catch the most hell under this system, from among those who are the victims of police terror and stop-and-frisk and profiling and all this, every day of their lives, who do get followed in the stores, or thrown up against the wall, or locked up for years for tiny possession or nothing at all, or who get caught up in all kinds of harmful things too because this system has no future or no options for them so they do get caught up, especially the youth, in killing each other or doing other kinds of harmful things to themselves and others. There's a real strategic question of what is it gonna take, and how do we right now, not some time in the future, but right now, how are we, as part of building this movement for revolution, stepping to those youth and struggling to actually bring these youth from among the most oppressed, the most without a future under this system, into this movement for revolution to become fighters not only for their own liberation but for the emancipation of humanity, and in an immediate way, including building in and going towards October 22. How do we go at that?

Dix: OK, I think that's a very important question both today and strategically. Because when we look at what we're doing today, we're actually moving to accelerate things towards the development of a revolutionary situation and bring closer the opportunity to actually go for revolution. And what I think we have to do is that we have to step to and challenge these youth. Bring to them what the reality actually is in a serious and substantive way and then struggle with them, because look, we go out all the time among these young people, we tell them, we lay out to them what's going on and we get a lot of, "yeah, I'm good," "right ons", and then keep on walking. And we have to say to these youth, "no, you're not good, none of us are good, we can't be good because this world is a horror." And here's how it's a horror but it doesn't have to be this way. But for it to be transformed through revolution, you and people like you gotta be a part of this movement for revolution. And then we gotta get into that with people because there is a lot of anger out there at the way that they're being treated.

The youth are angry especially about the way that they're being treated. But they don't see any other way that things could be and that's why they wave to you and keep on going or they say they're good because they don't think there's anything that could be done about it. And we have to confront them with the reality that not only is this bad, but yes, something can indeed be done about it.

A movement for revolution can transform the terrain in ways that are favorable for the development of the revolutionary movement, a revolutionary people, and an actual chance to make revolution. But they have to be a part of bringing that about. It can't be done by anybody else for 'em. They have to join this movement and we have to struggle with them. And part of what the struggle's gotta focus around is that they gotta get out of what they're into, which for a lot of 'em is a lot of destructive stuff in terms of what they're doing and for even more of 'em, even the ones that maybe ain't doing some of that destructive stuff now, the way that they look at things and the way that they think about things is destructive. Because looking out for number one, getting rich or dying trying, all of that is the ethos of the day. And a lot of the youth are taking that up. And it's not surprising that they would take it up in a system like this one where that's the ethos of the capitalists who run it. But getting into that and acting on that is about nothing that's any damn good for humanity.

But there is something that is good for humanity that they could be a part of and they could be with and that is a movement for revolution and a movement that is about emancipating all of humanity. And we have to put that to them, we have to seriously get into it with them. We have to bring out to them why these horrors continue to happen, where they come from, but also why and how they could be ended; and struggle with them around it and really make a fight for it. Because it isn't gonna happen—this is not like, you're not gonna roll downhill to bring forward these youth. It's gonna be a struggle, it's gonna be something that you really have to fight for.

But by fighting for these youth, we can actually win some of them, we can get them to join this movement for revolution and to represent for it. And as that begins to happen it reacts back on and impacts others among the youth. It also reacts back and impacts older people, many of whom are distressed by what the youth are into. But when they see the youth starting to get into something better, they're gonna welcome that, they're gonna support it and wanna see it happen. And we have to actually involve different sections among the people catching hell in that so that they're reacting on each other and helping each other. And then also that's gonna have its impact more broadly in society because when people see people who are catching hell, who are under the gun of this society, so to speak, standing up and fighting for justice, they're gonna be more drawn to stand with them. So that's gonna be impacting things as well.

That's the kind of difference it can make to fight through with some of these youth and win them to begin to becoming part of this movement for revolution. But we have to challenge them and we have to struggle with them for this to happen, you know, and make a determined fight for every youth that we can and get them to manifest as part of this. We gotta go to high schools in the communities of the oppressed.

But the key is we gotta challenge people and we have to struggle with them. And we have what we need to carry out that struggle because reality is impacting them in a way that has them opened up more and even asking some of these questions and we have the answers to these questions and the movement for revolution and the leadership we have for that movement in Bob Avakian and the strategy that we've developed for revolution and the vision of the world that could be brought into being. So we gotta take that to people and we gotta make a determined fight with them to get them to start taking it up.

Taylor: OK, so that was Carl Dix, founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party and an initiator of the Stop Mass Incarceration Network, leader in initiating and organizing right now, towards the 18th annual October 22 National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation. Thanks for sitting down with me. This has been Sunsara Taylor for Revolution newspaper, revcom.us.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.