In Memory of Yuri Kochiyama, 1921-2014

With Justice in Her Heart... All of Her Life

June 9, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

(Above) Yuri Kochiyama (lower left) with her two brothers and mother in a U.S. concentration camp in Jerome, Arizona, 1943. Photo: Courtesy of Yuri Kochiyama

Yuri Kochiyama speaking to students at a college campus in California. Photo: Courtesy of Yuri Kochiyama

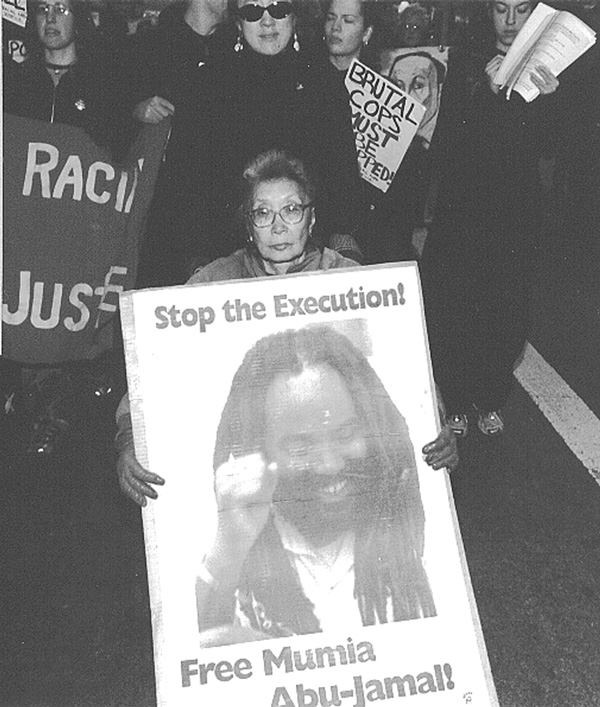

National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and Criminalization of a Generation, October 22, 1998, New York City. Photo: Special to Revolution

On June 1, Yuri Nakahara Kochiyama died at the age of 93. Yuri was a fierce, eloquent fighter against oppression and injustice, and tears of loss are flowing around the world because she was loved by so many people over several generations—not only in the progressive and radical movements and struggles here "in the belly of the beast" (as she liked to say), but on every continent.

Her life story is legendary, tracking huge social upheavals and changes of the latter decades of the 20th century, and stands as a testament to the powerful force of the liberation movements of those times. In her late 80s, Yuri said, "I sure wish I had opened my eyes to the real nature of this country, and the need to stand up and fight it, before I was in my 40s! But at least when I was shown how things really are—for Black people, and Native people, and prisoners, and everybody else who's oppressed—I was able to put 2 and 2 together, and figure out that I needed to join the movement and start fighting." For the next half century, she chose a fearless, passionate life that had at its center a love for the people and a tireless energy in the struggle against oppression.

Yuri's life shows how people can at any point come upon a door and find themselves compelled to step through it to take part in transforming the world—and in doing so, they themselves are transformed. We often speak of the '60s as a time when millions of young people were awakened to resistance and many to revolution. But Yuri was in her early 40s when the 1960s broke open.

Living in Harlem with her husband Bill and their six children, Yuri was involved in community and civil rights struggles. She developed an abiding friendship with Malcolm X, who sparked her awakening to the cause of Black liberation—pushing her beyond the principles of integration and nonviolent civil disobedience she had believed in to take up in thought and practice self-determination and self-defense for Black and other oppressed peoples. Yuri is perhaps most famous for the photograph in Life magazine taken seconds after Malcolm X was fatally shot, showing her cradling his head on her lap as he lay dying. But Yuri once told friends: "Yes, I happened to be there when Malcolm was assassinated. But I wish more people would understand how much I owe him for his friendship and leadership, how he gave me and many other people a real understanding of the racist system and a way to fight against it. Leaders like this are very, very precious."

Yuri also had close relationships with many other revolutionary nationalist leaders including Robert F. Williams (who gifted Yuri with her first Red Book of quotations by Mao Zedong) and Puerto Rican independentistas (in whose cause Yuri took part in the 1977 occupation of the Statue of Liberty).

For decades, Yuri was devoted to the cause of political prisoners, who she championed as brothers and sisters who must not be forgotten, imprisoned for commitment to political struggles that threaten the system and/or associations with radical and revolutionary struggles.

When Yuri spoke about her decades of support through legal battles and personal correspondence with dozens of political prisoners—she sometimes pointed to the importance of "making connections." She would talk about her own life as an example of the fact that just being mistreated by the system does not in itself push a person to fight against that abuse or the system causing it. In 1942 during World War 2, Yuri had been a young patriotic believer in the red-white-and-blue American Dream. Then she found herself among the 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans locked up in America's concentration camps. Solely on the basis of being Japanese, people were rounded up and forcibly removed from the West Coast, forced to leave behind homes, land, and property, and then held captive in 10 camps across the U.S. for the next three years. Just being imprisoned was a shock. Yuri, like so many Japanese in America, could not comprehend this immense and racist injustice in the country she considered her own. Her family was at the camp in Jerome, Arkansas, and there in the Jim Crow segregated South she began to see parallels between the lives of Black people and the treatment of the Japanese in America.

Later, Yuri often made the point that it was the concentration camp experience that gave her a connection both historically and viscerally to see the importance of standing with the political prisoners whom the U.S. government had targeted for their political work and/or associations that the system deemed to be threatening and subversive. "I cannot help but feel strongly about this [political prisoners], because I can never forget what we, peoples of Japanese ancestry, experienced during World War II because of hysteria, isolation, and absolutely no support... Yes, we were also political prisoners..." (Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama," by Diane C. Fujino)

The first political-legal case Yuri ever worked on was for Mae Mallory, a close associate of Robert F. Williams, the revolutionary nationalist leader in the early 60s who advocated armed self-defense by Black people. Both Williams and Mallory were framed on false criminal charges. From then on, the cause of political prisoners in the U.S., especially those connected to liberation movements of the '60s and '70s, was Yuri's most heartfelt work. Yuri exchanged personal letters with political prisoners, wrote articles about them, visited them, and stayed in touch with many of their attorneys and supporters. This included well-known political prisoners like Mumia Abu-Jamal, Leonard Peltier, and dozens of jailed Black Panthers and Republic of New Afrika leaders—as well as others not so well known.

Yuri was determined and fearless when it came to learning and taking on new things. She joined the struggle against the Vietnam war, supported national liberation struggles around the world, and was part of the fight against national oppression in the United States, including the movement that rose up among Asian-American students and youth. Even into her late 80s, Yuri continued to reach out as teacher, comrade, and mentor to new generations of young people of all nationalities. There are children (for at least three generations now) named after Yuri; rappers have songs about her; a university has a student center named in her honor.

Yuri's core outlook and philosophy was forged and driven by a profound sense of mission. In an interview with Revolution (then the Revolutionary Worker) Yuri was asked what she would say to those involved in different struggles, trying to figure out where they fit in and how to carry the struggle forward and she said, " I think part of the mission would be to fight against racism and polarization, learn from each other's struggles, but also understand national liberation struggles..." She was principled in uniting with all who she saw truly fighting oppression and in her own search for how to get justice in the world. And in this spirit she opened her heart and mind to those who brought other visions to the question of what it will take to achieve the full liberation of Black and other oppressed people in this country and the world.

We will always remember Yuri's ardent demand and indefatigable passion for real justice. We will always cherish and learn from her big heart and stubborn refusal to tolerate or be silent in the face of oppression. And we will always remember, love, and honor Yuri Kochiyama's wholehearted, and wholly lived, insistent "connection" between having a love for the people and oppressed—and never, ever, making peace with the system.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.