Comrade Will Reese—A Celebration and Commemoration, May 14, 2016

Ruby, Will’s wife

May 23, 2016 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Thanks so much for coming. I wish that he could be here. Anyway, I wanted to tell you something about Will. Unfortunately, one thing you might know about him, whenever he wrote something really important, stay up all night, he’d lose it on his computer. [Laughter] He would stay up all night and then when he was supposed to take it with him or whatever he was doing, it would disappear. And he would always be really calm, but then he would panic. Then I would be really calm and say, “Well if you saved it, if you saved it, it’s there.” Then he would say, “I didn’t save it.” So it wasn’t there.

This morning, I was making the changes on my speech, I saved it, but it wasn’t there. I’m going to try this—I mean, I have a first draft. And I know what happened, so I should be able to do this.

One thing I want to tell you now, we, many people met him for the first time when he came from Hawai’i to DC to Stop the Railroad of Bob Avakian. I did that, too. I think there were 200 volunteers, and I’m not going into that right now, we can talk about it at the reception if you like. But something he did there, everyone knew him because he really touched people, as everyone has been saying. So this is an example of him that I never forgot. We’d get all these red flags and we would go down to the slums. And buildings were burned out and boarded up. And on the corner of 14th and U [Streets] there would always be this really large group of heroin addicts, and people milling around, like dozens of people. We used to go down there with all of our red flags, a whole bunch of us, and it would become like, you know, go from a place of desperation to sort of like a celebration. And people would take up the red flags and the newspaper and they would join in with us and it was quite remarkable.

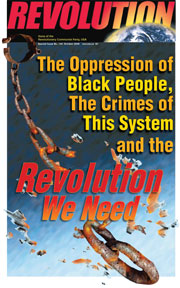

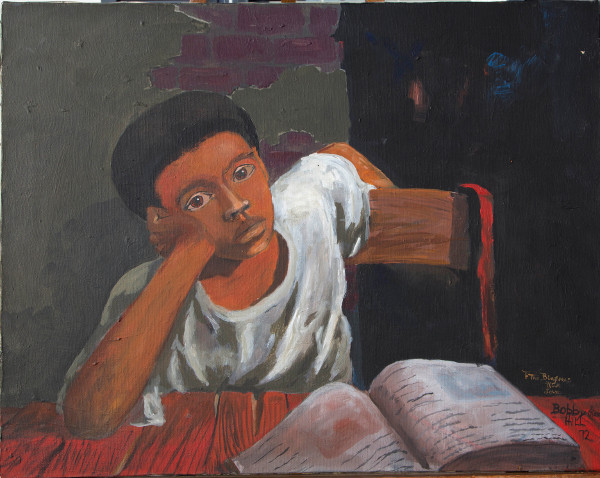

Painting by Will Reese. (Special to Revolution/revcom.us)

Painting by Will Reese. (Special to Revolution/revcom.us)

But Will... you can see he was a painter, an artist [referring to some of Will’s paintings that were on display], and he painted this really large picture of a Black man with his arms up in the air, breaking shackles with his wrists in a really powerful pose and he hung it up on the wall across from all these drug addicts. And all the people... it was like right in front of them. And then he gave them one of his speeches about you gotta join with us, we can do this. And he challenged people, don’t let them take this down. And it was up there, I know for the day, but the police did finally take it down. Anyway, I just thought... it really showed him.

And, then in the ’90s is when we got together, ’cause we had both ended up in the LA region. And we went out for coffee ’cause we knew each other. We were talking some about the region of the country where he grew up. It turned out that my mom is from about 80 miles away in Whitesburg, Kentucky. And he’s from where Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia come together in southwest Virginia. So we were like wow, this is really something. We’re from the same region of the country. I wasn’t from there, but I went there a lot in the summer. It is a place that haunts you. It was a place that we always wished... we always thought about how much that place needs a revolution because people there are so oppressed.

My mom, where she was from was a coal mining region, where a lot of the white people live in desperate rural poverty. I happened to mention that my grandfather was from Wise, Virginia. He said, “Oh, I know that place. We played football there. And we beat their team.” I said, “What was it like being a Black person growing up in this area?” And he said, “When we used to go to Wise, the white kids used to throw trash at the Black athletes. That’s why I was so glad we had beat them.” We got deeper into it.

He mentioned how his grandfather had known a 20-year-old man, someone he knew who had been lynched for talking to a white woman, or something like that. A few years later, I came to know that one of his distant cousins was actually decapitated by his white friends. I said, “His white friends, how did that happen?” He said, “Well, they were drinking, and things like that often happen in little towns around there.” Recently, I came across something that struck me. Before my mother was born, in Whitesburg, Kentucky, there was a Black man who was put in jail there. This was in about 1927. He was accused of murdering a man from Virginia. So a thousand white people from Whitesburg went and stormed the jail, and dragged out the Black man and took him over to Pound Gap, Virginia, and lynched him. And about a thousand people came from Virginia to participate. And so, we were both of us really driven to overcome these huge divides between people. We really had that in common. So we talked about those things when we first met.

Another thing we talked about was that... I told him, because he was really listening to me, and actually I had told most people: I had been the victim of a lot of the kind of violence and horror that is the experience of all too many women in this country and in this world, and really no woman escapes. The most violent things had happened to me when I was 21. At the time we were having coffee, I was 42 and he was 50. So it had been a long time. But I had gone on. I had just said to myself, I am gonna put this behind me and live my life. That’s what the common thinking is. Just keep going, and be brave. It was sort of like trying to swim through a river with a lot of dead bodies. You get out there, and you get out there, and then the dead bodies come floating to the surface, and you start bumping into them and they grab onto you. I was living in southern California with all the sunshine and flowers. I found myself thinking I had seen dead women in the bushes and under the underpasses—and there’s a lot of underpasses in southern California. I didn’t know why I was always telling people about what had happened to me. I couldn’t feel it. It was just something I would talk about. Really what I was doing was looking for a way to make sense of it all. And to find out how do you survive these things? I believed in a bright future. I knew that there didn’t have to be patriarchy, and hatred for women, and rape, and domestic violence in the world. After these crushing kinds of experiences, that’s what I was looking for was someone who could help me do that. He really listened to me. I think part of it is because he was somebody who had been through a lot and he had to bring together fragments himself.

Also, I sort of had thought that what you did, I looked at a revolutionary as someone really brave, someone with a lot of soldierly courage, like a freedom fighter. Part of what he understood was that people had a lot of great emotional complexity, or texture, as we used to refer to it. To get to a world without oppression you have to fight through all of that. And understand the complexity of human beings. He told me that I was like a person who had been dropped off in the middle of the ocean, and I was swimming to shore. And I can say he really saved my life, that’s what I think. Probably literally but also enabling me to change. He never gave up on me. He always told me I would make it back to shore. And I think I have.

BACK TO:

A Life Lived for Revolution:

Comrade Will Reese—

A Celebration and Commemoration

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.