Apartheid in South Africa: Decades of Serving the U.S. Empire

December 9, 2013 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

In the barrage of self-congratulatory eulogies for Nelson Mandela, spokesmen and ideologues for the rulers of the United States have conveniently whited out two things:

- The ghastly horrors of the apartheid system that enslaved the black people (and other non-white peoples) in South Africa from 1948 until the early 1990s; and

- The fact that the apartheid system was backed by, and served the interests of the rulers of the United States all this time—a source of massive profits and a strategic bulwark in their global empire.

Oh yes. They drag out their old quotes, issued over the years, deploring (in words) some of the most egregious crimes of the apartheid regime. But they cover up the depths of the horrors. And they lie about the reality that from 1948 the U.S. provided—sometimes indirectly, sometimes directly—the money, the guns, the “moral” cover, and the diplomatic endorsement that enabled all those crimes.

And they backed the apartheid regime to the hilt not because they lost touch with their basic core values, but as an expression of them. Most fundamentally, they backed the crimes of apartheid because of the essential nature of this global system of capitalism-imperialism.

The Reality of Apartheid

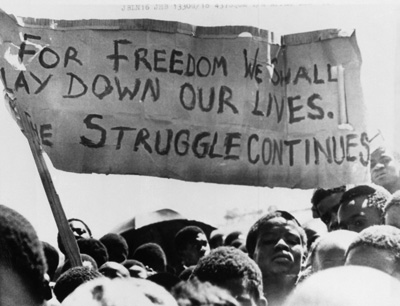

October 1976, Soweto, South Africa. Youth rally after the funeral of a 16-year-old black student, Dumisani Mbatha, who died in jail in the hands of the police. Photo: AP

It would take libraries and libraries to begin to tell the story of the horrors inflicted on the black people of South Africa by colonialism and imperialism—even just through the apartheid era that lasted from 1948 until 1994.

From the time of their arrival in the mid-1600s, through wars and massacres, the white settlers stole nearly all the usable land in South Africa. Nearly 90 percent of the land in South Africa was reserved for whites, while Africans—the vast majority of the population—were locked down in “Bantustans”—essentially mass concentration camps.

South Africa’s rich mineral resources including diamonds and gold produced billions in profits for global capitalism-imperialism, and made it possible for the “American way of life” to include the purchase of gold and diamond jewelry in shopping malls. But the mines were a hellish horror for the black people enslaved in them. Hundreds of thousands of black South Africans dug gold and diamonds out of the mines, without earning enough to feed and clothe their families. Miners spent nine to eleven months away from home, unable to see their families who were confined by pass laws to Bantustans. They lived in prison-like barracks, often without the most basic necessities like showers.

Black South Africans were driven into the cities in search of jobs, or worked on white-owned farms or in the mines to survive. Under “pass laws,” black South Africans were only allowed to travel from these Bantustans to work or for short trips. A black person caught without a pass faced severe consequences.

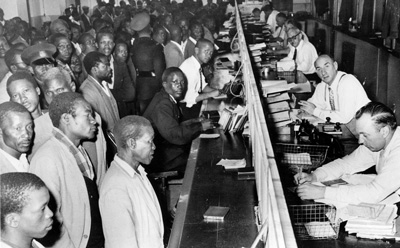

In South Africa after World War 2, apartheid further institutionalized and intensified vicious oppression of black (and other non-white) South Africans, who were locked down in prison-like "Bantustans," without the most basic necessities of life (like clean water or decent shelter). They were treated as non-humans, subject to fascist "pass laws" that governed their every movement. Above, black South Africans on line at the government office in 1960 to get new passbooks. Photo: AP

South Africa enforced a whole series of white supremacist laws. Marriages between white people and people of other races were against the law under apartheid. Laws limited the majority black population to owning a maximum of 13 percent of the land. The hated “Group Areas Act” confined blacks (and other non-whites) to officially demarcated ghettos. No representation for black people was allowed in South Africa’s governing parliament, and multi-racial political parties were against the law.

Black people driven to work in the cities lived in terrible conditions, with inadequate housing, poor health and transport services, and often no electricity. Those black people with “passes” to work in the cities were forced into squalid slums, often without even electricity. Women who came to live with their partners in the cities usually did so without passes, living the precarious lives of “illegals.”

The Sharpeville Massacre

The black people of South Africa never stopped struggling against their oppression, and the regime never stopped attacking them with whips, jailings, and guns.

From 1960 to 1982, three million non-white South Africans were forcibly and violently removed from their homes and relocated in “group areas” designed for them. Thousands of black South Africans were forcibly removed to the city of Sharpeville (originally "Sharpe Native Township"). Deep in the interior of northern South Africa, and removed from access to regional factory towns, conditions for blacks in Sharpeville were abysmal—14 homes shared one water tap and there were two bathing complexes in the entire city.

As in any mass struggle, there were different trends and political movements that opposed apartheid in South Africa. One was Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC). A more radical trend was the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). On March 21, 1960, the PAC organized the people relocated to Sharpeville to burn the hated passbooks used to enforce the pass laws. South African police opened fire on the crowd. Sixty-nine black people were killed and 178 wounded by police during the violence.

The Sharpeville Massacre ignited a powerful wave of struggle throughout South Africa against apartheid. And throughout the world, people protested their governments’ support for South Africa. The movement for “divestment,” an end to investment in South Africa, began to grow.

Blood on the Hands of the United States

How did the rulers of the U.S. respond as the world reacted with outrage and horror to the Sharpeville Massacre, and emerging exposure of the crimes of apartheid? With diplomatic endorsements of the regime, and economic backing.

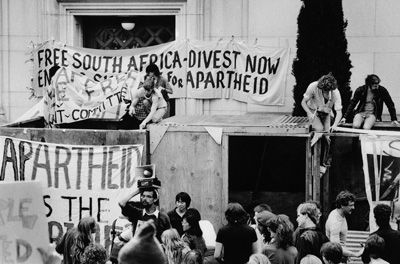

March 1986, University of California at Berkeley students build shanties blockading entrances to California Hall on campus demanding the university divest from South Africa. Photo: AP

As foreign investors became nervous in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre, outbreaks of struggle and rebellion across South Africa, and an emerging worldwide movement of protest against apartheid, a consortium of 10 banks led by Chase Manhattan provided South Africa with $40 million in rescue loans. The money stabilized the regime and sent a signal to the “international community” (of global oppressors and exploiters) that the U.S. imperialists were standing behind apartheid’s most appalling crimes.

As a matter of fact, from the start of apartheid to the mid-1980s and even beyond, the U.S. actively blocked any serious international sanctions or moves to isolate the South African regime, especially any sanctions that would impinge on the regime’s ability to massacre the black people within its borders, and invade and terrorize its neighbors.

While building a record of covering their asses with face-saving calls for reforming apartheid, the U.S. consistently blocked moves in the UN to impose economic sanctions or arms embargoes against South Africa. In 1963, U.S. ambassador to the UN Adlai E. Stevenson opposed a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa.

In 1974, the UN General Assembly voted 91 to 22 to reject South Africa's membership credentials, but the U.S. (and its imperialist partners the UK and France) vetoed a Security Council resolution to expel South Africa.

The Murder of Stephen Biko

Stephen Biko emerged as an inspiring leader of resistance to apartheid in the 1970s, and beyond that was a founder of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) that opposed the oppression of black people in South Africa in any form. Like every serious political, cultural, and intellectual challenge to the regime, Biko was “banned”— not allowed to speak to more than one person at a time or to speak in public, restricted to one district, not allowed to write publicly or speak with the media. It was illegal to quote anything Biko said, including speeches or simple conversations.

In spite of this, Stephen Biko and the BCM organized resistance to apartheid across the country, including the Soweto Uprising of June 16, 1976. Students from numerous Sowetan schools began to protest in the streets of Soweto in response to being forced to study in Afrikaans, the language of the dominant section of white settlers in South Africa. Tens of thousands went into the streets. The regime responded with brutality that shocked the world. Police opened fire on the students, killing a still untotaled number of unarmed protesters—estimates of the dead range from 176 to 700.

After Soweto, the regime went after Biko with renewed fury. They arrested him on August 18, 1977, under South Africa’s “Terrorism Act No 83 of 1967,” tortured him, and beat him to death.

Biko’s death served to further intensify and radicalize the struggle in South Africa, and around the world. (For more on this, see Donald Woods’ book, Biko, Henry Holt publishers, New York, 1987, as well as the movie Cry Freedom.) On October 7, 2003, the South African justice ministry announced that the five policemen accused of killing Biko would not be prosecuted because the time limit for prosecution had elapsed and because of insufficient evidence.

A Strategic Outpost for the U.S. Empire

Even as the apartheid regime grew more exposed and isolated, the rulers of the United States continued to back it—albeit at times covertly, but often overtly.

In the context of the extreme isolation of the apartheid regime, the “human rights” president, Jimmy Carter, appointed Andrew Young, a Black man associated with the civil rights movement, as ambassador to the UN and called for reform in South Africa. But in 1977, the U.S. abstained from a UN General Assembly resolution recommending an oil embargo against South Africa, effectively blocking the embargo.

Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan, was more overt about U.S. sympathies, interests and objectives, declaring that the U.S. should work "with a friendly nation like South Africa" that "strategically is essential to the free world…"

Reagan’s statement—coming from the mouth of an unabashed cheerleader for everything the United States has always really stood for, tells you much of what you need to know about the essence of what the U.S. brings to the world. U.S. imperialism has always defined the “free world” as including many of the most brutal, depraved, oppressive regimes on earth, from the genocidal mass murderer Rios Montt in Guatemala to the white supremacist rulers of South Africa.

And throughout this period, even when the U.S. took formal positions opposing apartheid in international forums, or when it was unable to block diplomatic, economic or military sanctions, it arranged for its closest allies and puppets to keep the oil and arms flowing into South Africa. When the Organization of Arab Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an oil embargo on South Africa in 1973, the Shah of Iran, a U.S. puppet, stepped in to become South Africa's major oil supplier.

The roots of the tight bonds between the rulers of the U.S. and apartheid go even deeper than the fact that the U.S. ruling class is racist to the core and saw the rulers of South Africa as “kin”—though they are, and did!

At the very time South Africa was viewed with outrage by people all around the world, and carrying out the most heinous crimes, justified with the most Nazi-like white supremacist immorality, the United States needed South Africa.

The deep ties between the U.S. and the apartheid regime were rooted in the reality that the U.S. presides over a worldwide system of imperialism which feeds, and must feed, vampire-like off the blood-soaked superprofits it extracts from Asia, Africa and Latin America, and the apartheid regime was, for a time, a key pillar of that—including as military enforcer for the interests of the U.S. in southern Africa.

In the 1970s and 1980s in particular, the rulers of the U.S. saw a (relatively) stable South Africa as a strategic military bulwark to defend their interests in southern Africa—a region where they faced challenges from anti-colonial and national liberation movements as well as from a rival Soviet Union which branded itself socialist (and was called that by the rulers of the U.S.) but which had restored capitalism and headed a rival imperialist bloc (see Revolution special issue "You Don't Know What You Think You "Know" About...The Communist Revolution and the REAL Path to Emancipation: Its History and Our Future").

By the mid-70s, independence movements backed by the Soviet Union had come to power in the former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique—countries in southern Africa with large borders and with strategic resources of their own (like Angola’s large oil reserves). The consolidation of a bloc of stable southern African countries aligned with the Soviet Union was seen by the rulers of the U.S. as an intolerable challenge to their empire.

The U.S., working through South Africa, set up or adopted and enlisted some of the most depraved terrorist groups in modern history to wage terrible wars against these new regimes. And South Africa itself continued to forcibly occupy what is today the country of Namibia, where a tiny strata of white settlers had seized over 99 percent of all the usable land.

The wars launched by these U.S./South African proxies, UNITA in Angola and RENAMO in Mozambique, resulted in a regional reign of death and terror. From 1977 to 1992, an estimated one million people died in the war in Mozambique, and the war in Angola claimed even more lives. Millions more in each country were displaced.

The bloody hands of the South African military were all over this slaughter, including training of these terrorist forces, direct military intervention, and funding. And through a combination of aid to South Africa, open aid, and CIA secret funding, the U.S. orchestrated, sponsored and enabled these two decades of horrors. The U.S. openly aided UNITA, and RENAMO shared an office address in Washington, D.C. with the reactionary Heritage Foundation. In 1982, the U.S. urged the International Monetary Fund to grant South Africa $1.1 billion in credit, an amount that happened to be equal to the increase in South African military expenditure from 1980 to 1982.

Through this entire period, the U.S. arranged for its allies, especially Israel, to train the South African military, provide weapons technology, and train “intelligence” agencies in torture. In 1981, the South African military used Israeli drones in combat against Angola. That same year, Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon spent 10 days on the ground with South African forces in Namibia. Most Israeli aid to the apartheid regime was covert, including significant steps by Israel to provide South Africa with nuclear weapons.

The End of Apartheid But Not the End of U.S. Crimes

In 1972, the “Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act” was introduced in the U.S. Congress, which would have banned direct flights to the U.S. by South African airlines, and imposed significant economic sanctions.

It was 14 years before that act passed—over the veto of Ronald Reagan. By the mid-1980s, the U.S., through unofficial channels, had begun negotiations with the imprisoned Nelson Mandela (even as they kept him on their “Terrorist Watch List” until 2008!). By the late 1980s, the U.S. had begun the process of overseeing the transition from apartheid to new forms of oppression in South Africa. But that was not because the rulers of the U.S. suddenly grew a conscience.

There was a huge international movement against apartheid. Some of the most influential figures in music came together in Artists United Against Apartheid, and students on campuses in every part of the world were confronting authorities over their shameful complicity with the crimes of the South African regime.

So the indomitable struggle of the people of South Africa and the global struggle against apartheid were significant factors in the U.S. change of tactics vis-à-vis South Africa.

The other defining factor was the collapse of the Soviet Union. That major geopolitical event created new freedom for the U.S. to repackage the forms of oppression in South Africa, and to negotiate new relationships (on the basis of decades of waging massive terrorist attacks) with the governments in Angola and Mozambique, and the independence forces in Namibia.

With the collapse of its Soviet rivals, and in a move to stabilize South Africa, the U.S. orchestrated a transition to new forms of oppression in South Africa. It did so only after getting assurances that the country would continue to serve the U.S. empire.

Formal apartheid was ended in 1994. Nelson Mandela was released from jail and became the first black president of South Africa. The obscene, overt segregation against black and other non-white peoples had ended. But the basic situation for the vast majority of black people was not improved, and the fundamental causes of their exploitation and oppression remain.

What the U.S. Brings to the World… Really

Now, in the wake of the death of Nelson Mandela, the U.S. ruling class and their mouthpieces drag out their old meaningless, face-saving diplomatic calls for reform of apartheid over the years, and initiatives they took to explore what kind of deals they could make with Nelson Mandela and the ANC, all to portray themselves as longtime (if occasionally flawed) opponents of apartheid, and a powerful force for the ideals of freedom and democracy around the world.

These are lies. From the imposition of apartheid in 1948, to the moment they decided different forms of oppression would better serve their interests in the early 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the rulers of the U.S. were the main prop of apartheid. Sometimes overtly—as when U.S. banks moved to bail out South Africa in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre. Sometimes covertly—as when oil producing Arab countries refused to send oil to South Africa and the U.S. arranged for its puppet the Shah of Iran to fill the gas tanks of the South African bulldozers, bombers, and armored personnel carriers that spread terror from the black townships of South Africa to the country of Namibia. When it was too awkward to openly send military advisors and weapons, the U.S. subcontracted the job to Israel.

But the basic truth is that the immoral, bloody reign of apartheid was a source of vast profits and a strategic military outpost for U.S. imperialism, and its existence is hard to imagine without the foundational backing it got from the U.S.

And none of this is a “blemish” on the record or nature of U.S. imperialism. It is a profound example of the essence of what it is the United States brings to the world.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.