Interview with Carl Dix

The System Says Black Life Has No Value—There MUST Be a Response

March 17, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

In the last issue of Revolution, we began to publish excerpts of an interview that Revolution did with Carl Dix, from the Revolutionary Communist Party and an initiator of the Stop Mass Incarceration Network. We are continuing with new excerpts this week and will be publishing more next week.

The Revolution interview began with a discussion of the mistrial of Michael Dunn in Florida. Dunn murdered Jordan Davis in cold blood and was tried, but not convicted of this murder. The interview has been edited for publication.

Carl Dix: On the trial of Dunn for the murder of Jordan Davis, this came down to Amerikkka (and I spell it with KKK) declaring once again that Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect. If you look at this case and the trial on this case, you have some teenagers playing their music loud in a car. You have a guy pulling into the gas station, doesn’t like the music, tells them to turn it down. They won’t, there’s an argument back and forth, but the kids are going to listen to their music. And it was Black youth listening to rap music and the guy who wanted it turned down was a white guy who thought that music was crap and thug music, and he pulls out his gun and begins to fire at them, and continues firing after their car has pulled away and is driving off at high speed trying to save their lives. Then this guy gets put on trial for this and claims self-defense. He comes up with an imaginary weapon—a shotgun that no other person on the scene had seen and has never been found—and tears up over having to drive from the scene of this killing to his hotel so that his dog could relieve his bladder, but very coldly and without emotion talks about killing a young Black man. And stripped down to its essence, his testimony was a call for white supremacists to come forward and have his back, that he was striking a blow for “embattled” white people in this society and he should be supported for that, that these Black people are getting out of their place and white people need to start killing some of them to get them to change their behavior. And what I’m saying here is what he actually wrote letters to his family members from jail and what he said in phone calls from jail. The prosecution had the transcripts of those phone calls and those letters—and didn’t bring any of that into court, and I’m going to come back to that in a minute. But this is what happened and you get a jury that can’t convict this guy for murder. This was the system declaring that Black life has no value. And you put this on top of the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman and the refusal of the system to convict Zimmerman for it and you see that there’s a message: Black youth have a target on their backs, a target that any cop and now any white racist could use for target practice, claim self-defense and expect to be vindicated in doing that.

This is unacceptable

This is unacceptable. This is a declaration that people cannot allow to be made without a response being mounted to it. Because, look, there’s youth who know that this target’s on their backs, that they could have a confrontation with a cop or with a white racist and end up dead. There are parents who give their children guidance: this is what you must do and this is what you must not do if you meet up with a police officer. Now that guidance has to extend to: you’re running into a white guy, you have to watch it, you have to do this, you have to not do that. Knowing all the while that no matter how good that guidance is, no matter how well their children follow that guidance, it may mean nothing in one of these confrontations. Because look at Jordan Davis, look at Trayvon Martin, look at Amadou Diallo, look at Sean Bell and many other names that I could talk about—Jonathan Ferrell1 down in North Carolina. What did they do wrong? Where did they act in ways that brought this on them? It came down to being Black or Latino and in the wrong place at the wrong time.

It’s unacceptable that whether people live and how they live can be determined by the color of their skin—this is something that must not be accepted. That’s why when I issued the statement right after the verdict in the Jordan Davis case, I said: this shows us again why we need a revolution, why we have to get rid of this system. Because you’re talking about brutality and oppression that has been built into the fabric of this Amerikkkan capitalist system from the very beginning. And there’s a lot of questioning out there among people about why does this happen, where does this come from, and what, if anything, can be done about it? And that’s a discussion that needs to be unleashed very broadly in society and we gotta be right in the middle of it, bringing out why does it happen, where does it come from, and how it flows from the very operation of this system.

Because when you look at the history of Black people in this country it has always been a thing of being integrated into and ground up under the process of the production of profit in this country. In the beginning it was enslavement and being worked from “can’t see in the morning to can’t see at night,” producing tobacco and then cotton and getting nothing for doing that—just enough to keep you going so you could come back out to the fields and work the next day. And then you had a whole system of laws, institutions to enforce those laws, and customs and the way that things were to keep that in place and to mobilize all of white society as part of keeping that in effect. Slavery was ended post-Civil War, but you still had Jim Crow segregation, people largely on the same plantations where they’d been enslaved, but now they were sharecroppers producing often the same crops and being robbed for it by the plantation owners who may have enslaved them previously. This is what people were dealing with. And a whole system of Jim Crow laws, tradition, custom, to enforce it, and again white society was mobilized to do that. Because you had the sheriffs who could arrest people for vagrancy which came down to being in the wrong place at the wrong time with no white man to speak for you. And then you could be imprisoned and leased out where you were worked as a slave—slavery by another name is what it came down to. If you were deemed to be out of your place by the white mob, you could be lynched. If you were a Black person in an area where a white mob, decided that some Black guy had gotten out of his place, you could be lynched because the record of lynching in this country records all of these incidents—where they couldn’t find the person they were looking for so they grabbed some other people, where someone spoke out against the lynching and then got lynched themselves. This all went on.

Only the forms have changed

The forms have changed once more. It became a thing not of sharecroppers on the plantation but Black people being drawn into the cities to work in the factories. But again, what did that come down to? The bottom tier of those workforces, working some of the hardest, most dangerous jobs, getting paid the least. This is something that I actually know something about because I worked in a steel mill. And you go into the steel mill and there was a Black labor gang where the people in that labor gang could work all of the jobs in the place and even often trained the young guys coming in—and they told me about how white guys would come into the plant and they would get trained on the jobs that paid more, were cleaner and not as dangerous, but the Black workers could not move up to take any of those jobs. Also I know about it because I got scars from having worked there when I got burned nearly to death in that plant. So this is the kind of thing that people moved into as they got off the plantations. So it was not easy street, it was still on the bottom, being viciously exploited.

But even now there’s been a further development of that. The process of production has been internationalized so those jobs are no longer available for people in the inner cities. And what it is, is that right now large numbers of youth cannot be profitably exploited by capitalism-imperialism at this point. And what those youth face is no future within this system, there’s no way for them to legitimately survive and raise families. And the response of the authorities has been one of criminalizing these youth—that’s where that target that I talked about earlier comes from. These youth are treated as permanent suspects, guilty until proven innocent if they can survive to prove their innocence. So that’s what we’re up against right now, and we’re talking, again, about horrific oppression that is built into the fabric of this capitalist system. This is oppression that can’t be reformed away; it can’t be tweaked out of existence. It’s really going to take revolution—and nothing less—to get rid of it once and for all.

Now, I mentioned some things which I do want to go back to. Because Angela Corey, whose office prosecuted George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin and couldn’t get a conviction, also did the case of Jordan Davis and she was unable to get a conviction on murder. And this office did have these vicious racist statements from Michael Dunn that bore pretty much directly on what he actually did, like why people need to start killing these Black thugs and get them to change their behavior. He said this repeatedly over the phone, in writing—the prosecution had it and made no attempt to bring that in. They didn’t even bring it in to impeach his credibility when he said: I have never had racist sentiments. This was part of his testimony. This is the guy who said white people need to start killing Black people to get them to change their behavior. The prosecution made no attempt to bring that in, and it’s not that Angela Corey’s office is just plain incompetent. It’s that in cases like these where it is George Zimmerman on trial for criminalizing and murdering Trayvon Martin, a young Black man, or Michael Dunn on trial for criminalizing and murdering Jordan Davis, a young Black man—they “forget” how to prosecute.

But when it comes to running Black and Latino people into jail in all kinds of cases and like that, there’s no forgetfulness there. Corey’s office is very efficient at doing that. I met people... there’s one family of a 12-year-old who Corey attempted to get sent up for life—not until he became an adult, but for the rest of his life. She didn’t fully get that, but she got decades on him. Another case where a youth was charged with having carried out a robbery with a BB gun—he goes to school one morning and the cops come into the school and arrest him with no warrant. Their evidence is that there is a phone that he may have had access to that has something to do with this robbery, but the access that he had was the same access that a number of other people in the school had. They hold him, interrogate him for 24 hours, and force a confession out of him. This youth is now doing 49 years in prison. So what you have is you have an office that is very good at imprisoning Black and Latino people but forgets how to do it when it’s somebody going up for crimes committed against Black and Latino people.

Revolution: You went to Jacksonville on February 26 along with Juanita Young, the mother of Malcolm Ferguson who was murdered by New York City police. After the mistrial of Michael Dunn, the Stop Mass Incarceration Network added Jordan Davis to its call for that day. Could you speak to how you saw that and what you thought needed to be done in the face of that, why you and Juanita Young went to Jacksonville, and some of what you learned?

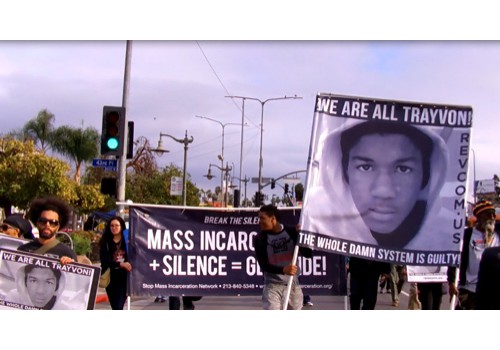

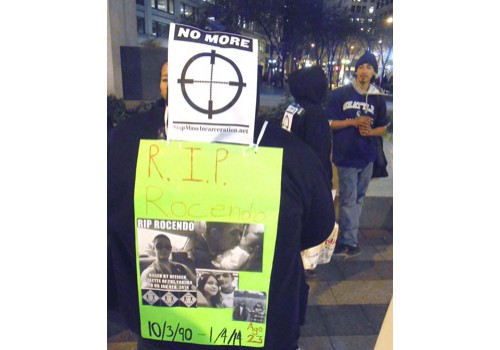

Carl Dix: The Stop Mass Incarceration Network issued a call for a nationwide day of outrage and remembrance around Trayvon Martin on February 26 because that was two years since he was murdered by George Zimmerman. And when the trial of the killer of Jordan Davis ended—the Stop Mass Incarceration Network decided to add Jordan Davis to that day of outrage and remembrance. And this was actually very important because there was a lot of questioning about: is there anything we can do about this? We marched when Trayvon’s killer was exonerated and then here we have it happening again. The system refuses to convict a murderer. And some people were even thinking and voicing that maybe we just have to get used to this, we have to accept this. And it was very important that a call went out: No, we must not accept this and cannot accept this and we don’t have to either. And the call from the Stop Mass Incarceration Network was for: Hoodies Up on February 26! Reports on what happened on the 26th are still coming in. And one place that I really suggest people go is they go to the website revcom.us—because that’s a site where you can find out not only what happened on February 26 but what’s happening.... with the movement for revolution, that is very needed that we in the Revolutionary Communist Party are forging, what that’s doing, what’s happening in this movement of resistance to mass incarceration, what’s happening in the movement of resistance to the attacks on women in this society, and everything. And you can get guidance for how to do that, and you can also find out about the leadership we have for this revolution in Bob Avakian, the leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party. And part of why we don’t have to accept it is because revolution is not only needed but it’s possible, and its possibility is greatly enhanced by the work that Avakian’s doing. And people need to check that out, engage it, get into it, and spread the word to others around it.

Revolution: I want to ask you a little bit more about the 26th. I think it would be good to talk about what would have happened if SMIN had not called what it did call and what effect that would have had, so people can appreciate the impact their actions have. And to talk some... did this reach into the media? Did it have an impact?

Carl Dix: There was a sentiment of: can we do anything about this? Not that people felt that it was anything less than a horrible outrage, but a sense of maybe we can’t do anything. And it was very important that that sense was gone against, that sense was engaged and struggled over. And we began to notice it very sharply right after the verdict came down. I remember being in Harlem and encountering some youth who listened to me speak—people had read my statement, and I got up and I spoke and expounded on some things. And they listened intently, but then when we approached them and asked them for their thoughts one of them said, “I have no thoughts.” And then the other said, “I’ve got a lot of thoughts, but it wouldn’t make any difference if I told you about them. It would just make me madder, and what could we do about it anyway?” And we realized we had to get into it with these two young people, and they ended up taking material to go into their school and to mobilize people, getting that it would make a difference if they remain silent in the sense of hammering in that assessment—nothing we can do, we just gotta roll with this stuff. But it makes a difference the other way if people like them—they and people like them—begin to act, begin to counter that sentiment, begin to say “no we don’t have to accept this.” And begin to grapple with this question of revolution and what kind of world could be brought into being—is that possible and what does that mean that people like them need to do? Which they were taking a beginning step of by getting Revolution newspaper and taking some of the palm cards around the National Day of Outrage and Remembrance, that they were actually beginning to engage that and step into it.

And this had to be spread societywide because while we had to engage it on the streets with people, we also had to get it out there to reach people that we won’t be able to run into on the street. And we worked at getting it out through social media, on Facebook, tweeting about it, spreading the word. And it did have impact because right now we know of 18 cities—including something came in last night, this morning, that it happened in Birmingham on the 26th—that people took up the Hoodies Up! call. It happened in the areas where the Stop Mass Incarceration Network already has some organization, or beginning organization. And that was important. People in the Oakland area did a rally at Fruitvale Station, the scene of the murder of Oscar Grant by a cop on New Year’s Day of 2009. People acted in Chicago, in New York. But also we began to find out that there were places were the Stop Mass Incarceration Network had no contact with people who heard about this call for the Hoodie Day and did something. There were people in a sorority in Houston. People at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee organized an event which they posted at SMIN's website and which got covered in the media there. But there were also media things like Bethune Cookman, which is a historically Black college in Florida—some students there did a vigil. This began to be taken up more broadly, and what it does speak to and address is that there was a feeling that something needed to be done. There was anger about this, a feeling something needed to be done, but that anger had to be tapped into and mobilized and organized. And that was the role that the call from the Stop Mass Incarceration Network took up and acted on and brought forth a response, and a response that... it was on BET that afternoon that this was happening and that organizers were calling for it to happen across the country. There was some newspaper that has a regional spread in the South—not a Black newspaper—a more mainstream one, had something about it and talked about the Bethune Cookman vigil. But then I saw the same write-up without the Bethune Cookman vigil somewhere in Louisiana.

So the word began to be spread, people took this up, and it was very important that in the face of... coming off of the anger people have, but also in the face of questioning if there was anything that expressing this anger could do, any role it could play, it was very important. Because when people look back at the Trayvon Martin murder and the exoneration of the killer, it made a very big difference that people took to the street, and took to the street in significant numbers—not large enough, but in significant numbers. I guess there were thousands of people who marched into Times Square in New York, people in Los Angeles who blocked traffic on an interstate—things like that happening all across the country. And it does make a difference if these are met with determined response. Because if they’re not, there’s a message involved in this: a message of the criminalization of these youth, permanent suspects, targets on their backs, no rights that white people are bound to respect—all of this is being declared. And if that becomes something that people accept as just the way things are, it is not only going to continue to happen but it is going to escalate, it is going to get even worse. Because there is really a call for the white supremacists, fascist foot soldiers, to come forward and play a role in enforcing this putting of the oppressed back in their places. And that’s all a part of the mix that’s going on right now. Also there was coverage on the Essence magazine website, NBC News had it on its site, Democracy Now! had some very good coverage on its site....

That was actually an important arena in which things happened because you think back to... as motion developed around Trayvon Martin’s murder you had things like pro basketball players wearing hoodies, the Miami Heat doing a team picture in hoodies, Amar’e Stoudemire of the NY Knicks putting on his hoodie as he’s out going through the practice line shooting lay-ups and stuff. So that was an important expression, and for the cast of Raisin in the Sun to take a stand in solidarity...

Dwayne Wade was at the heart of the Miami Heat taking a stand, he brought the whole team onto doing it.

Stay tuned for more...

1. Last September, 24-year-old Jonathan Ferrell wrecked his car in a one-vehicle accident. He knocked on doors seeking help; a white woman called the police saying that a Black man was trying to break into her house. When Charlotte, North Carolina police arrived they shot him 10 times, dead in the street, as he approached their car with his hands open. [back]

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.