Interview with Carl Dix

Mass Incarceration and Criminalization of Youth in Amerikkka—and the Vision for October Month of Resistance

April 2, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Revolution recently caught up with Carl Dix, from the Revolutionary Communist Party and an initiator of the Stop Mass Incarceration Network, after what was a very intense month of February—a month in which there was the mistrial of the racist murderer Michael Dunn and the failure of the courts to convict him for the killing of Jordan Davis; demonstrations and other forms of resistance that took place on the anniversary of the murder of Trayvon Martin, which also took in Jordan Davis this year; and then Obama's speech on February 27, setting forth a program which he claimed would deal with the situation facing Black and Latino youth. Short excerpts have appeared in previous issues of Revolution. Here is the fuller interview, which has been edited for publication.

The interview began with a discussion of the mistrial of Michael Dunn in Florida. Dunn murdered Jordan Davis in cold blood and was tried, but not convicted of this murder.

~~~~~

Carl Dix: On the trial of Dunn for the murder of Jordan Davis, this came down to Amerikkka (and I spell it with KKK) declaring once again that Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect. If you look at this case and the trial on this case, you have some teenagers playing their music loud in a car. You have a guy pulling into the gas station, doesn’t like the music, tells them to turn it down. They won’t, there’s an argument back and forth, but the kids are going to listen to their music. And it was Black youth listening to rap music and the guy who wanted it turned down was a white guy who thought that music was crap and thug music, and he pulls out his gun and begins to fire at them, and continues firing after their car has pulled away and is driving off at high speed trying to save their lives. Then this guy gets put on trial for this and claims self-defense. He comes up with an imaginary weapon—a shotgun that no other person on the scene had seen and has never been found—and tears up over having to drive from the scene of this killing to his hotel so that his dog could relieve his bladder, but very coldly and without emotion talks about killing a young Black man. And stripped down to its essence, his testimony was a call for white supremacists to come forward and have his back, that he was striking a blow for “embattled” white people in this society and he should be supported for that, that these Black people are getting out of their place and white people need to start killing some of them to get them to change their behavior. And what I’m saying here is what he actually wrote letters to his family members from jail and what he said in phone calls from jail. The prosecution had the transcripts of those phone calls and those letters—and didn’t bring any of that into court, and I’m going to come back to that in a minute. But this is what happened and you get a jury that can’t convict this guy for murder. This was the system declaring that Black life has no value. And you put this on top of the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman and the refusal of the system to convict Zimmerman for it and you see that there’s a message: Black youth have a target on their backs, a target that any cop and now any white racist could use for target practice, claim self-defense and expect to be vindicated in doing that.

This is unacceptable. This is a declaration that people cannot allow to be made without a response being mounted to it. Because, look, there’s youth who know that this target’s on their backs, that they could have a confrontation with a cop or with a white racist and end up dead. There are parents who give their children guidance: this is what you must do and this is what you must not do if you meet up with a police officer. Now that guidance has to extend to: you’re running into a white guy, you have to watch it, you have to do this, you have to not do that. Knowing all the while that no matter how good that guidance is, no matter how well their children follow that guidance, it may mean nothing in one of these confrontations. Because look at Jordan Davis, look at Trayvon Martin, look at Amadou Diallo, look at Sean Bell and many other names that I could talk about—Jonathan Ferrell1 down in North Carolina. What did they do wrong? Where did they act in ways that brought this on them? It came down to being Black or Latino and in the wrong place at the wrong time.

It’s unacceptable that whether people live and how they live can be determined by the color of their skin—this is something that must not be accepted. That’s why when I issued the statement right after the verdict in the Jordan Davis case, I said: this shows us again why we need a revolution, why we have to get rid of this system. Because you’re talking about brutality and oppression that has been built into the fabric of this Amerikkkan capitalist system from the very beginning. And there’s a lot of questioning out there among people about why does this happen, where does this come from, and what, if anything, can be done about it? And that’s a discussion that needs to be unleashed very broadly in society and we gotta be right in the middle of it, bringing out why does it happen, where does it come from, and how it flows from the very operation of this system.

Because when you look at the history of Black people in this country it has always been a thing of being integrated into and ground up under the process of the production of profit in this country. In the beginning it was enslavement and being worked from “can’t see in the morning to can’t see at night,” producing tobacco and then cotton and getting nothing for doing that—just enough to keep you going so you could come back out to the fields and work the next day. And then you had a whole system of laws, institutions to enforce those laws, and customs and the way that things were to keep that in place and to mobilize all of white society as part of keeping that in effect. Slavery was ended post-Civil War, but you still had Jim Crow segregation, people largely on the same plantations where they’d been enslaved, but now they were sharecroppers producing often the same crops and being robbed for it by the plantation owners who may have enslaved them previously. This is what people were dealing with. And a whole system of Jim Crow laws, tradition, custom, to enforce it, and again white society was mobilized to do that. Because you had the sheriffs who could arrest people for vagrancy which came down to being in the wrong place at the wrong time with no white man to speak for you. And then you could be imprisoned and leased out where you were worked as a slave—slavery by another name is what it came down to. If you were deemed to be out of your place by the white mob, you could be lynched. If you were a Black person in an area where a white mob, decided that some Black guy had gotten out of his place, you could be lynched because the record of lynching in this country records all of these incidents—where they couldn’t find the person they were looking for so they grabbed some other people, where someone spoke out against the lynching and then got lynched themselves. This all went on.

The forms have changed once more. It became a thing not of sharecroppers on the plantation but Black people being drawn into the cities to work in the factories. But again, what did that come down to? The bottom tier of those workforces, working some of the hardest, most dangerous jobs, getting paid the least. This is something that I actually know something about because I worked in a steel mill. And you go into the steel mill and there was a Black labor gang where the people in that labor gang could work all of the jobs in the place and even often trained the young guys coming in—and they told me about how white guys would come into the plant and they would get trained on the jobs that paid more, were cleaner and not as dangerous, but the Black workers could not move up to take any of those jobs. Also I know about it because I got scars from having worked there when I got burned nearly to death in that plant. So this is the kind of thing that people moved into as they got off the plantations. So it was not easy street, it was still on the bottom, being viciously exploited.

But even now there’s been a further development of that. The process of production has been internationalized so those jobs are no longer available for people in the inner cities. And what it is, is that right now large numbers of youth cannot be profitably exploited by capitalism-imperialism at this point. And what those youth face is no future within this system, there’s no way for them to legitimately survive and raise families. And the response of the authorities has been one of criminalizing these youth—that’s where that target that I talked about earlier comes from. These youth are treated as permanent suspects, guilty until proven innocent if they can survive to prove their innocence. So that’s what we’re up against right now, and we’re talking, again, about horrific oppression that is built into the fabric of this capitalist system. This is oppression that can’t be reformed away; it can’t be tweaked out of existence. It’s really going to take revolution—and nothing less—to get rid of it once and for all.

Now, I mentioned some things which I do want to go back to. Because Angela Corey, whose office prosecuted George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin and couldn’t get a conviction, also did the case of Jordan Davis and she was unable to get a conviction on murder. And this office did have these vicious racist statements from Michael Dunn that bore pretty much directly on what he actually did, like why people need to start killing these Black thugs and get them to change their behavior. He said this repeatedly over the phone, in writing—the prosecution had it and made no attempt to bring that in. They didn’t even bring it in to impeach his credibility when he said: I have never had racist sentiments. This was part of his testimony. This is the guy who said white people need to start killing Black people to get them to change their behavior. The prosecution made no attempt to bring that in, and it’s not that Angela Corey’s office is just plain incompetent. It’s that in cases like these where it is George Zimmerman on trial for criminalizing and murdering Trayvon Martin, a young Black man, or Michael Dunn on trial for criminalizing and murdering Jordan Davis, a young Black man—they “forget” how to prosecute.

But when it comes to running Black and Latino people into jail in all kinds of cases and like that, there’s no forgetfulness there. Corey’s office is very efficient at doing that. I met people... there’s one family of a 12-year-old who Corey attempted to get sent up for life—not until he became an adult, but for the rest of his life. She didn’t fully get that, but she got decades on him. Another case where a youth was charged with having carried out a robbery with a BB gun—he goes to school one morning and the cops come into the school and arrest him with no warrant. Their evidence is that there is a phone that he may have had access to that has something to do with this robbery, but the access that he had was the same access that a number of other people in the school had. They hold him, interrogate him for 24 hours, and force a confession out of him. This youth is now doing 49 years in prison. So what you have is you have an office that is very good at imprisoning Black and Latino people but forgets how to do it when it’s somebody going up for crimes committed against Black and Latino people.

February 26 National Day of Outrage and Remembrance for Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis

Revolution: You went to Jacksonville on February 26 along with Juanita Young, the mother of Malcolm Ferguson who was murdered by New York City police. After the mistrial of Michael Dunn, the Stop Mass Incarceration Network added Jordan Davis to its call for that day. Could you speak to how you saw that and what you thought needed to be done in the face of that, why you and Juanita Young went to Jacksonville, and some of what you learned?

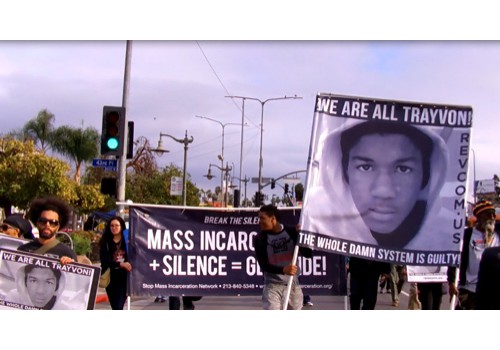

Carl Dix: The Stop Mass Incarceration Network issued a call for a nationwide day of outrage and remembrance around Trayvon Martin on February 26 because that was two years since he was murdered by George Zimmerman. And when the trial of the killer of Jordan Davis ended—the Stop Mass Incarceration Network decided to add Jordan Davis to that day of outrage and remembrance. And this was actually very important because there was a lot of questioning about: is there anything we can do about this? We marched when Trayvon’s killer was exonerated and then here we have it happening again. The system refuses to convict a murderer. And some people were even thinking and voicing that maybe we just have to get used to this, we have to accept this. And it was very important that a call went out: No, we must not accept this and cannot accept this and we don’t have to either. And the call from the Stop Mass Incarceration Network was for: Hoodies Up on February 26! Reports on what happened on the 26th are still coming in. And one place that I really suggest people go is they go to the website revcom.us—because that’s a site where you can find out not only what happened on February 26 but what’s happening.... with the movement for revolution, that is very needed that we in the Revolutionary Communist Party are forging, what that’s doing, what’s happening in this movement of resistance to mass incarceration, what’s happening in the movement of resistance to the attacks on women in this society, and everything. And you can get guidance for how to do that, and you can also find out about the leadership we have for this revolution in Bob Avakian, the leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party. And part of why we don’t have to accept it is because revolution is not only needed but it’s possible, and its possibility is greatly enhanced by the work that Avakian’s doing. And people need to check that out, engage it, get into it, and spread the word to others around it.

Revolution: I want to ask you a little bit more about the 26th. I think it would be good to talk about what would have happened if SMIN had not called what it did call and what effect that would have had, so people can appreciate the impact their actions have. And to talk some... did this reach into the media? Did it have an impact?

Carl Dix: There was a sentiment of: can we do anything about this? Not that people felt that it was anything less than a horrible outrage, but a sense of maybe we can’t do anything. And it was very important that that sense was gone against, that sense was engaged and struggled over. And we began to notice it very sharply right after the verdict came down. I remember being in Harlem and encountering some youth who listened to me speak—people had read my statement, and I got up and I spoke and expounded on some things. And they listened intently, but then when we approached them and asked them for their thoughts one of them said, “I have no thoughts.” And then the other said, “I’ve got a lot of thoughts, but it wouldn’t make any difference if I told you about them. It would just make me madder, and what could we do about it anyway?” And we realized we had to get into it with these two young people, and they ended up taking material to go into their school and to mobilize people, getting that it would make a difference if they remain silent in the sense of hammering in that assessment—nothing we can do, we just gotta roll with this stuff. But it makes a difference the other way if people like them—they and people like them—begin to act, begin to counter that sentiment, begin to say “no we don’t have to accept this.” And begin to grapple with this question of revolution and what kind of world could be brought into being—is that possible and what does that mean that people like them need to do? Which they were taking a beginning step of by getting Revolution newspaper and taking some of the palm cards around the National Day of Outrage and Remembrance, that they were actually beginning to engage that and step into it.

And this had to be spread societywide because while we had to engage it on the streets with people, we also had to get it out there to reach people that we won’t be able to run into on the street. And we worked at getting it out through social media, on Facebook, tweeting about it, spreading the word. And it did have impact because right now we know of 18 cities—including something came in last night, this morning, that it happened in Birmingham on the 26th—that people took up the Hoodies Up! call. It happened in the areas where the Stop Mass Incarceration Network already has some organization, or beginning organization. And that was important. People in the Oakland area did a rally at Fruitvale Station, the scene of the murder of Oscar Grant by a cop on New Year’s Day of 2009. People acted in Chicago, in New York. But also we began to find out that there were places were the Stop Mass Incarceration Network had no contact with people who heard about this call for the Hoodie Day and did something. There were people in a sorority in Houston. People at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee organized an event which they posted at SMIN's website and which got covered in the media there. But there were also media things like Bethune Cookman, which is a historically Black college in Florida—some students there did a vigil. This began to be taken up more broadly, and what it does speak to and address is that there was a feeling that something needed to be done. There was anger about this, a feeling something needed to be done, but that anger had to be tapped into and mobilized and organized. And that was the role that the call from the Stop Mass Incarceration Network took up and acted on and brought forth a response, and a response that... it was on BET that afternoon that this was happening and that organizers were calling for it to happen across the country. There was some newspaper that has a regional spread in the South—not a Black newspaper—a more mainstream one, had something about it and talked about the Bethune Cookman vigil. But then I saw the same write-up without the Bethune Cookman vigil somewhere in Louisiana.

So the word began to be spread, people took this up, and it was very important that in the face of... coming off of the anger people have, but also in the face of questioning if there was anything that expressing this anger could do, any role it could play, it was very important. Because when people look back at the Trayvon Martin murder and the exoneration of the killer, it made a very big difference that people took to the street, and took to the street in significant numbers—not large enough, but in significant numbers. I guess there were thousands of people who marched into Times Square in New York, people in Los Angeles who blocked traffic on an interstate—things like that happening all across the country. And it does make a difference if these are met with determined response. Because if they’re not, there’s a message involved in this: a message of the criminalization of these youth, permanent suspects, targets on their backs, no rights that white people are bound to respect—all of this is being declared. And if that becomes something that people accept as just the way things are, it is not only going to continue to happen but it is going to escalate, it is going to get even worse. Because there is really a call for the white supremacists, fascist foot soldiers, to come forward and play a role in enforcing this putting of the oppressed back in their places. And that’s all a part of the mix that’s going on right now.

Revolution: Also there was coverage on the Essence magazine website, NBC News had it on its site, Democracy Now! had some very good coverage on its site. It was very important that people understand. I’m just seconding and filling out some things. I also noted that the cast of the classic play about an African-American family in a racist neighborhood in Chicago, Raisin in the Sun, which was a play from the early 1960s that’s now being revived on Broadway, did something in solidarity with Trayvon Martin and in remembrance of the day. Were there other cultural expressions that you know of?

Carl Dix: That was actually an important arena in which things happened because you think back to... as motion developed around Trayvon Martin’s murder you had things like professional basketball players wearing hoodies, the Miami Heat doing a team picture in hoodies, Amar’e Stoudemire of the NY Knicks putting on his hoodie as he’s out going through the practice line shooting lay-ups and stuff. So that was an important expression, and for the cast of Raisin in the Sun to take a stand in solidarity.

Revolution: Dwayne Wade was behind a lot of that, wasn’t he?

Carl Dix: Dwayne Wade was at the heart of the Miami Heat taking a stand, he brought the whole team onto doing it. The cast of Raisin in the Sun—that’s actually pretty significant when you look at what that play is about, going back to the 1960s and the question of Black people trying to move into a white neighborhood and what they ran into. And then today looking at what Black people are running into, and the cast wanting to make a statement around that has some special significance. There also were 10-minute plays—six 10-minute plays—that were put on at the National Black Theater in Harlem earlier in February under the theme of Trayvon, Race and Privilege. It was actually seven playwrights because one of the plays was a collaboration—these seven playwrights all went at the question of Trayvon’s murder, the criminalization of Black youth, from different angles – some going more directly for the George Zimmerman/Trayvon Martin confrontation, others taking up things like police murder of Black youth. One play even went at this from the perspective of humor to underscore this thing of Black youth are being criminalized in this society. I thought that the plays—and by design—were trying to go at: this is a question that people have to look at, this is something that people gotta deal with. And I went to the opening and closing—I think there were five or six performances up in Harlem at the National Black Theater—and each time it was basically overflow crowds. The ushers were going around: “If you’ve got a seat next to you, raise your hand”—trying to fill in all the seats. And there were still people standing in the back.

And almost everybody stayed around for the discussions that they had afterward, and there was a lot of questioning of where is this coming from, why does this happen, and what if anything can we do about it? Including some questioning of, is this basically our fault? Do we have to get our young people to pull their pants up, take off the hoodies and start wearing vests or sweaters or something like that? Is that the way to deal with this? Or is this something that is being done to Black people and being done to Black youth? And who or what is behind it? And there was really lively discussion, including with the participation of revolutionary communists who were bringing out there is a system behind this. Because, look, if the youth stop sagging their pants, are the cops going to be less unleashed to brutalize and murder them? Is the court system going to be less operated in a way that targets them? Is the fact that Black people are not... the capitalist system has no way to profitably exploit most of these Black youth (and Latino youth, for that matter) that are growing up in the inner cities of this country—is that going to be changed? No, it’s not.

And in fact there is a positive side to the fact that Black youth, Latino youth, are not disposed toward accepting the bullshit that is being brought down on them. And in relation to that I think back to the 1960s, and so do the people who run this country—that it was very important that a section, particularly of Black youth, were not disposed to take this bullshit, and that there were leaders like Malcolm X, say, who was a nationalist, but one who called out the system and sided with and stood with those youth who did not want to take this bullshit. And that was very important in pulling the covers off of Amerikkka and exposing what this country was about and bringing forward others to join in the struggle, and he spearheaded a broader revolutionary movement to rock the system back on its heels. And frankly it’s a positive thing that there are youth today who don’t want to take the bullshit. Now that’s gotta be led, that’s gotta be given guidance, the youth have gotta be struggled with to get out of shit that they’re in right now, and get with the revolution. But that spirit of not taking this shit is something that they can and must bring into the movement for revolution—so that’s a positive thing.

What the Murders of Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis Mean—And Must Come to Mean

Revolution: This was something of a watershed event, the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman and then Zimmerman’s acquittal, and then coming on top of that, the mistrial of Michael Dunn for the murder of Jordan Davis. What does it mean to people and what must it come to mean?

Carl Dix: I made the point about how this is a declaration that Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect. People themselves are looking at historical analogies in relation to this. Because the “no rights that white people are bound to respect” is drawn from the 1857 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. It was a guy who escaped from slavery and who was brought into court in order to try to bring him back, and the Supreme Court ruled: hey, you got no rights, you’re property, you don’t really exist. And this has been a statement and a social relation that has continued to exist in this country. When Trayvon was murdered, and again when Jordan was murdered—and in each case the killer was not convicted. There were people talking about: I don’t want to be here 50 years from now talking to my children or my grandchildren about another Black youth that’s been murdered and nothing is done. And they’re thinking back to Emmett Till who was lynched in the 1950s by two white men because he supposedly whistled at a white woman. And they got put on trial before an all-white jury that within an hour found them not guilty, and then they sold their story about lynching this Black youth to a national magazine. But that’s how bold they were about it—they sold the story to this national magazine about how they had committed this horrific crime. And people are looking back and saying: Why does this keep happening? And I don’t want to be doing this 50 more years down the road. So it was a moment when a lot does get concentrated. Are they going to continue to be allowed to get away with this?

It is very important and it was very important that in our coverage in Revolution newspaper coming off of the murder of Trayvon and the exoneration of his murderer that we said they must not be allowed to get away with this and they cannot be allowed. This has to actually become a period where people look back and say: boy, a lot of people started along the path to coming to understand that this system is just no damn good, it is illegitimate, and it’s gotta be gotten rid of, and it’s going to take revolution—nothing less to do that. And that’s a message that needs to go out to people. It has to go out in a much broader way, in an escalated way, because this is what people need to be engaging, grappling with, and it’s what they need to be getting with. And this was the message that some of us revolutionaries were bringing out at the talkbacks after those Trayvon plays, and we gotta project this through society. Because that is what needs to happen off of this. We are talking about vicious oppression that’s built into the fabric of this system, and people hate this—a lot of anger—and not only among the people who directly suffer it. Because after the Trayvon verdict there were large numbers of white people who came out to these demonstrations and who were saying: I don’t want to live in a society where this happens, where whether somebody lives or dies is determined by the color of their skin.

And it’s important to tap into that anger and that sentiment and give it forms of expression because there’s another side that comes out in relation to that. There’s a way in which the powers-that-be can’t help but recognize the sentiment that’s developing among people and they take steps to misdirect it, to try to channel it back into the system. Like on the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington last year there was a lot of talk about: we need a new Civil Rights movement, we need to get activated in trying to get more reforms of the way the system works and to try to hang onto some of the reforms that were being taken back that we thought had been won in the past. Because voting rights are under assault all across the country—which was an important battle in the 1960s. Not because you can vote your way to freedom, but it is an expression of how people are viewed in society if the color of their skin, whether they’re Black or Latino, or other things can be used as reasons to deny them the right to vote. So there’s a lot of effort being made to channel people back into the system, and it’s very important that the actual reality be brought out. We’re talking about mass incarceration and the criminal injustice system. This is not a system that is basically working and there are a few excesses that need to be reformed or tweaked. It is institutions that have been unleashed to target people—that’s a key part of the program of suppression, targeting Black and Latino people...and that it needs to be fought, it needs to be stopped, and to get rid of it once and for all is going to take revolution—nothing less.

Revolution: It seemed that in the summer, if I remember correctly, at first Obama was not even trying to speak to this, and at a certain point, after people had done the actions at Times Square, after they had seized the I-10 freeway in Los Angeles, after even some people who used to be called Uncle Toms actually spoke out in dismay and anger. Only at that point was Obama compelled to try to step to the head of this and rein things in.

Carl Dix: The Black president has been something that has been deployed as part of trying to bring people back into the killing confines of this system, and even back to his initial election and the way in which it drew people in. That was an important thing because I remember a lot of his supporters were themselves beginning to chafe at his silence in the wake of the verdict around Travyon. And he did come out with a statement trying to situate himself in relation to the growing anger that was developing. I think it was the thing he said about if he had a son he would look like Trayvon, and then he said a little bit later: Trayvon was me a few decades ago, that could have been me. And then he tied that to his overall approach to this question which consistently comes down to blaming the masses of oppressed people for what the system does to oppress them, and proposing some surface reforms and tweaks that aren’t going to get at the heart of the problem.

Going to the Scene of the Murder of Jordan Davis

Revolution: I want to get to that in a minute. But first, I do want to hear a little bit more about the delegation made up of you and Juanita Young, who is the mother of Malcolm Ferguson who was murdered by New York City police in the year 2000 and who herself has been a very important and consistent fighter against all police murder and all police brutality. If you could talk a little bit about why you went to Jacksonville, why you thought it was important to go, what you learned, what people did there, and how you would answer people who would say the problem is with Florida and Florida’s extreme racism.

Carl Dix: We decided to do the delegation down to Jacksonville because Jacksonville was the scene of the crime. It was where Jordan Davis had been murdered and where the mistrial of his murderer occurred, where the system refused to convict the murderer for an open and naked murder. So we felt it was important to help bring national attention and bring some people from the movement of resistance to mass incarceration and all its consequences down to Jacksonville. And people down there really welcomed the fact that we came down. They were like: we gotta delegation coming down from New York! They knew about me because Cornel West and I had done the video calling for February 26th to happen, and it turned out they had played the video for a lot of people. So they welcomed the fact that we were going down and in fact when I spoke at the rally there were people like: “Oh, that’s the guy from the video! I didn’t know he was coming.” And people really warmed to that.

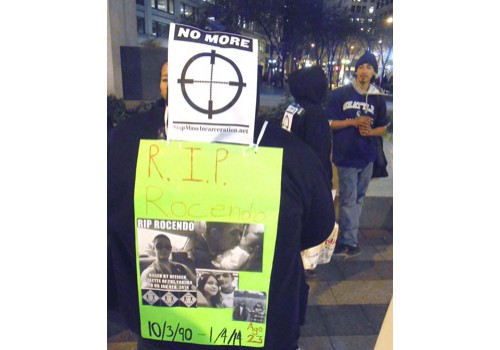

Fifty people came out and pretty much the overwhelming majority of them were people who had directly felt the lash of the criminal injustice system. There were about eight family members of a guy who had been killed by the police in front of the home he had grown up in, while his mother, his two children, two nieces and a nephew watched. They brutally beat him, stopped, went back to their car and put on gloves for some reason, came back, beat him some more, and then shot him. And all this happened while his family and more than a dozen other people watched. These cops have not in any way been punished for this.

Then there were a number of people who had family members who were in prison, and some of them were doing one-family campaigns to try to expose what had happened. And one of the families had gone so far as to look at the procedures and policies of the prosecutor’s office in dealing with juveniles because there are really a lot of juveniles who get sentences that amount to spending the rest of your life in prison. They tried to give a 12-year-old natural life without parole for a crime he committed as a 12-year-old. A 17-year-old has gotten 49 years for a robbery committed with a BB gun that there was very little evidence tying him to, but the cops arrested him in school one morning with no warrant, interrogated him for 24 hours with no legal representation or parent, and forced a confession out of him. This family has documented 89 violations of the prosecutor’s office policies. And the prosecutor’s office response is: we do that all the time. They didn’t deny it, didn’t say you’re wrong, they said we do that all the time. Think of all of the people who have been run through it, and especially all the juveniles—because this man was a juvenile. So all of this goes on. There were people like that, several families like that.

And a number of formerly incarcerated people who are coming out of having been in jail and feeling like... one man told me: I gotta give back because, look, I did what they got me for, I was dealing. I gotta give back because I feel like I was poisoning my community before but now I want to be part of... well, he actually put it like this. He said: “Revolution is like a tsunami, and I want to be a part of bringing that tsunami into being so that it can clean away everything that’s holding people back.” And then as we talked about it, he was like: “I’m not clear about how this happens.” I said, “Well, there’s something to that analogy but you gotta really focus on: it can look like a tsunami, but if there’s not a core of people working to bring it into being, working to contribute to creating the conditions through which that revolutionary upsurge and wave happens and can give it leadership to make sure that it does go in the direction that it can and needs to go in terms of sweeping away the old structure and bringing in a totally different and far better way for people to live.” And he said: “Yeah, that’s the thing I’ve been trying to think about. How do you do that? Is that how it happens?” And then we zeroed in on BA Speaks: REVOLUTION– NOTHING LESS! as something he and others need to get into.

And then people marched to prosecutor Angela Corey’s office and it was very spirited. I mean, people really wanted to get down to that office to display their determination for this to stop. One thing that got raised to me quite a bit was that Florida is different, and some of you don’t know how it is. And, look, Florida is a concentration of the way the criminal injustice system in this country has been unleashed to beat people down, lock them up, and lock them away, including locking them away for horrific periods of time. When they dedicated the new courthouse Angela Corey made a speech along with some other public figures, and she said: “I want to give a million years of jail time in this new courthouse.” This is what she said publicly on the dedication of this building. So it does reflect some of this concentration of it. And there is an old South aspect of it in the way that it targets Black people as well as a new South aspect because there’s also the rounding up of immigrants and the processing of them for deportation. So there is something about Florida. And if Nina Simone redid her song, which she can’t do since she’s passed away, but if Nina Simone’s song “Mississippi, Goddamn!” was redone you’d probably want to add a Florida, Goddamn! stanza or two to it. But it really is a concentration of what happens all across the country. Because I was talking with people about how there’s been exposure of, in Brooklyn, the prosecutor’s office has... this one cop in particular, there’s dozens of cases where he used the same informant to convict people. And this guy gets fed the information: here’s the story. He gets brought into court, testifies to it, people get sent away. And it finally got broken in the case of this guy named Ranta, but then it turns out there are dozens of cases where this same informant is the only evidence that put people away for decades. So now they’ve got dozens of cases that they’re trying to figure out: Do we have to let all of these people out, is there any way we can keep it together and keep them in?

So this kind of stuff happens all across the country, but there is a certain concentration in Florida. Because one thing is the case of Marissa Alexander, the Black woman who fired a warning shot when she was being confronted by her ex who had beaten her previously and was threatening to kill her. At that point she got a gun, fired a warning shot, and chased him off. She ended up being charged with aggravated assault against him and convicted and sent away for 20 years and the court ruled that Stand Your Ground in her case did not apply. And it was Angela Corey’s office that was prosecuting this case too. That conviction ended up being overturned and she now has a new trial coming up in July, but along with overturning the conviction, the appeals court ruled that she has to face three charges of aggravated assault because there were two children in the house and if she gets convicted on all of them they have to be served consecutively, consecutive 20 year sentences. So in other words, she’s now facing 60 years. This is the approach that Angela Corey’s office takes. So there is something about Florida, but it is a concentration of things that happen all across the country.

It is really a horrific miscarriage of justice. I mean, a woman who has been beaten by her ex a number of times, and that’s part of why he’s an ex, defends herself, but doesn’t kill the person, decides it’s just enough to fire the warning shot and that’ll send him off. And it worked. So she didn’t kill the person who was threatening her, but she was being threatened and defending her life and she gets taken into court and there’s no Stand Your Ground that’s applicable there, and not even... because there’s a basic right to self-defense in the legal system in this country. That gets thrown away too. And that’s what’s going down, and it is very important that this case be fought through and that Marissa not be sent back to jail. This would be a tremendous outrage if she got sent back to jail.

Obama's Poisonous "My Brother's Keeper" Initiative

Revolution: You’ve also talked about how Obama began to change up a little bit some of the way he was presenting things, and felt he had to, right after the... not after the verdict on George Zimmerman but after the response from masses of people to the verdict on Zimmerman.

Carl Dix: Actually it turned out that February 26 was also the day that Obama held a meeting in the White House and then the next day made a public announcement of an initiative that he’s launching called My Brother’s Keeper. It’s an initiative to bring private foundations and companies into contributing money to set up programs to mentor Black youth and to try to save some of them from the things that await them out in the streets. Look, it was not accidental—the timing of that, that the meeting happened on the 26th, the anniversary of the murder of Trayvon Martin. And in fact, he had the parents of both Trayvon and Jordan Davis at this meeting and at the public announcement the next day, along with a number of other people that pointed to exactly what this thing was about. And this initiative is pure poison. In a certain sense, it was a really ugly display. Because you got the guy who presides over the system that is criminalizing these young people, that’s warehousing people in prison, that’s treating formerly incarcerated people like less than full citizens, and he starts off his talk about America’s a place where you can make it if you try hard. Bullshit! America is a place where people who work the hardest... who worked harder than the enslaved Africans? And who got less for it? You know, the wealth and power of this country can all be taken back to the dragging of African people here in slave chains and the theft of the land from the native inhabitants. And that is where America came from, that’s what it grew up on, so don’t tell me about America’s a place where if you try hard you can make it. That is exactly not real, that’s exactly not true. Then he goes on to say, well, let’s not talk about what the problem is, let’s just grab a hold of what works and go with that. Well, he actually identifies a problem, but in talking about not talking about what the problem is, he doesn’t want people getting into and looking at the fact that this is something that the system is doing to people. But he brings forward an assessment of the problem, and that is that the problem is people and their lack of personal responsibility. And particularly it’s Black men not playing their role in society: fathering children but not being there in the family for them, not helping to raise their children, not playing the role of a man in society. And, again, turning reality on its head, blaming people being oppressed for what the system is doing to oppress them, and then bringing forward a prescription for change that is not going to address that oppression but actually tighten it up.

And there are a couple of things I gotta get into off of this. One is Obama says: I’m doing this to strengthen America. I think back to the 1960s and one of the sharp questions around which people contended and struggled quite a bit is: Is this a movement... coming from the movement of Black people and then being taken up by others... is ours a movement to get our place in America, get our seats at the table? Or is America not only our problem, but the world’s problem? And what came forth in the 1960s was a very powerful section of the movement that was saying the problem is America. And we see our struggle in alliance with people around the world who are fighting against America. I think about some of the people in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee who were down South, dealing with lynch mob terror and all of that, working with Black people down there to register to vote and to do other things, who were also saying hell no, we won’t go to Vietnam and beginning to identify with the Vietnamese people in their struggle against U.S. imperialism. I think of the Black Panther Party putting out a call that Black soldiers should not go to Vietnam and fight for the U.S., that our fight was against U.S. imperialism. And all of that, which I remember very vividly personally because I had to grapple with all of that when I got my orders to go to Vietnam after I got drafted in the 1960s. And sentiment like that was a part of what led me to refuse to go to Vietnam.

So I’m thinking: Obama is doing this to strengthen America. I say to people being ground down by this system: You don’t want to get drawn into strengthening America because America is what’s grinding you and people all around the world like you down. And where you need to be standing is: How do we all get out from under America by making revolution and getting rid of American imperialism and all the imperialisms in the world? You can’t go with: We gotta strengthen our oppressor and that somehow that’s in the interests of people in this country or anywhere else in the world. That was one thing that really struck me about it.

Another thing is you’re supposed to be trying to do something to help Black men who are in bad situations in this country—well, who does Obama bring to this goddamned meeting? He brings and honors Michael Bloomberg, former New York mayor, Mr. Stop-and-Frisk. Bloomberg did a lot around the situation of young Black men—he unleashed his police force to stop-and-frisk them in numbers that ended up that they were stopping and frisking more Black men between the ages of 15 and 24 than there were in New York City. Which means some of them would get stopped and frisked numerous times by the cops This is somebody who you’re going to buddy up with and partner up with to do something about the situation of young Black men? It ain’t going to be something good if you’re doing it with Michael Bloomberg.

Obama also brings there Bill O’Reilly, the Fox News fascist commentator. He calls himself the first two, but I had to add that last point to get to the reality of what this man stands for. And this is a guy who had been recently talking about: well, look, the problem with Black people... one of the things he’s saying right now is the problem with Black people is rap music and you gotta do something about those rappers because that’s a disease that is poisoning America. But he also talks about the problem with Black people is that you’ve got all of these women who are having children out of wedlock and that that is what’s devastating Black America and it’s dragging the whole country down—so you gotta do something about that.

This brings me to another thing that hits me about Obama’s initiative, what was missing from what he said: We’re going to do something about what’s happening to Black men and it’s kinda like, Black women, they’re kinda okay. Maybe some problems there, but they’re kinda okay, we just have to do something about the situation that Black men face. And again, that is not the reality. It is not the reality that Black women are doing okay and we just have to do something in relation to the men. Because when you look at what’s happening in this country, you look at waves of evictions of families that are headed by single women—it happened in the wake of the economic meltdown of 2007 and 2008. This is women and their children being set out on the street because of developments in the overall economy that stripped away from them any way that they had to survive and keep the family together. This is going on. You’ve got cuts in the food stamp program, which again is hitting very hard at women and their children and women who have the main responsibility to see to it that the children are fed. That’s leading to spreading hunger in this country. You even have things like breast cancer... you know, like 20 years ago the rate at which women died from breast cancer was relatively even. But the rate that Black women die from breast cancer has skyrocketed over the past 20 years. You have situations where Black women are dying one-and-a-half and two times as often as white women of this disease.

And then there was just an article in Revolution newspaper about the prison in Alabama, I think it’s called Tutwiler. And what it displayed was a report that had come from the federal government about the widespread... it’s a women’s prison... the widespread instances of rape of the prisoners by male guards. The article just provided a snapshot, but that snapshot was horrific. It was that guards just forced themselves on women. Then guards do things like: You want some toilet paper? You want a tampon? Then you gotta have sex with me. And it is becoming a thing where that’s how you operate in the prison. I mean... toilet paper, tampons—we’re not talking about people trying to do outlandish shit, it’s just basic necessities. But the way that you get that basic necessity is that you allow this fucking pig to force himself on you. This is the situation that people are being put in, and it took me back to slavery and the way in which if you were a female who was enslaved on the plantation, any white man with ties to the plantation could rape you because you were not a human being that any transgressions could be committed against. The only problem you might run into is if some white man with higher status on the plantation decided he wanted to be the exclusive one to rape that female slave—that’s the only way you run into any problem. And those conditions are being repeated today, and frankly it is a form of enslavement, and some of the things that are coming down on it. So this is going on.

Well, if you begin to talk about incarceration, you can’t leave women out of that conversation. One, because the fastest growing segment of people in prison is Black women—that’s actually the fastest growing segment. So you gotta have that in there. There are fewer women in prison than men, fewer Black women in prison than Black men—that is true. But the fastest growing segment is Black women. But even more important than that, when you send someone to jail, the whole family is doing time. So you send a man to jail—there are children tied to that, there are partners and spouses tied to that, or people are working together to try to raise children. There are mothers tied to that, and that whole family has their life enmeshed in the criminal justice system. You’re like: Can we go and visit and sometimes it’s a long trip? So, can we make that long trip, do we have the money to make that long trip? The phone call... you get robbed by the phone companies on that. So it does come down to talking about can we relate to the brother who’s in prison or do we pay the electric bill? These kinds of questions get thrown up before people. So you can’t separate that out and say you’re going to deal with it and say I’m going to deal with Black men and what they’re up against but the women have no relation to that.

Now, part of what is posed here [by Obama] is a prescription of: strengthen male right and kind of like the Black man has to much more become the figure who’s in control of the women and children. This is a prescription that’s being put forward in this. And it’s something that’s actually been argued for—you could take this back to the Moynihan report back in the 1960s, I believe, or 1970s—I forget exactly when. But Senator Moynihan said that the single most important factor in the problems in the Black community was the Black family being pulled apart and there no longer being men in the house and that’s the thing that you gotta deal with.

And then you’ve had like... George W. Bush used to like to push this thing of: we’re going to get people married. All of this ignores the larger forces that are at work here—the way in which the process of production has become globalized and there is not a role for increasingly large numbers of Black and Latino people to be profitably exploited in that process of production. And that’s the backdrop against which two-parent families aren’t being formed in large numbers among Black people. That’s what’s going on but the way it’s being addressed is this thing about: we gotta get the men to man up and to play their responsibility, be the father in the house, the head of the household. And it is really calling for a strengthened patriarchy: male domination within Black families. That to me is part of what ties into this thing of leaving the women out of it—that it is asserting that that needs to happen and that that’s a development that needs to go down.

Now, in relation to Obama’s initiative, there’s been a lot of criticism of it. But a lot of the criticism misses the point. Because one of the things often said is that it’s too little and it’s too late. People look at the figure of $200 million [for the initiative] and talk about how much goes into the military budget, how five times that amount is going to Ukraine, and all this kinda stuff. Not enough and why didn’t you do this sooner? Well, that doesn’t get to the heart of it because what is actually at issue… and they also raise the thing about why is it private and not the government doing something. That doesn’t actually get to the heart of it because what this is, is an attempt to get in front of some things. It is in part a response to that anger that came out around Trayvon, that was still there around Jordan Davis, and saying: we’re dealing with it, don’t worry. We’ve got a program for it, we’ve got a plan—and trying to suck people in behind that approach and that plan. And that we can bring a few more people through the meatgrinder—because that’s what’s in operation in Black communities and Latino communities across the country, a grinder that is breaking the bodies and crushing the spirits of countless millions of people. And this is an approach that says: Well. maybe we can bring a few more people through that grinder. And that’s the way that this initiative is going to work. And to talk about it as too little and too late misses that it is actually aimed at keeping the operation of that meat grinder going.

We Need Revolutionary Role Models, Female and Male

Revolution: I want to go back to this point you were making about how Obama’s speech on February 26th actually representing a proposal for strengthening patriarchy. In Unresolved Contradictions, Driving Forces for Revolution, Bob Avakian says, look, this is a very complex question. BA does two things: first he draws on that book Rebirth of a Nation, and the point that’s made in there is that Booker T. Washington was bringing forward in the late 1890s and early 1900s this notion of accommodation to the system coupled with a big emphasis on male right within the Black family and it’s very conservative, patriarchal, heavy religious; and that, on the contrary, Ida B. Wells was the first real anti-lynching activist. And that these were two trends. So one point is that if you’ve got 900,000 African-American men in prison, it’s not a mystery where the father is. I’d like to hear a little bit more on Obama’s speech—the problem he was actually implicitly pointing to and the solution he was proposing.

Carl Dix: That’s important to get back to because I talked about how Obama began with: if you work hard you can make it, if you try in America, but he also ended up on what has become for him his kind of signature punch line of “No Excuses”—no excuses for Black people who don’t succeed in America, and pretty explicitly saying: don’t use racism as an excuse. Let’s actually get down to it: there is brutal and vicious oppression coming down on people, and it’s coming down on people because of the system that he’s presiding over. And he’s saying: look, the system will beat you down, will grind you up, but no excuses—if you don’t succeed it is your own fucking fault. That is what objectively is being said in coming down on this. Because he’s talking about these absent dads. Well, I’ll tell you where a whole lot of them are: 900,000 of them are in prison. And hundreds of thousands are in prison for things like simple drug possession—that’s what that comes down to. And your system and the way that it operates has historically, since the 1970s, been using wars on drugs that have targeted Black people, that have led to the criminalization of Black youth, led to a reality where Black people use drugs pretty much in relation to their proportion of the population—not excessively in relation to whites. But then when you look at who gets arrested for drug use—that is disproportionately Black people. And then when you look at who gets convicted—that’s even more disproportionately Black people.

So it is the system and the way in which it works, its very operation, and the conscious policies of the ruling class—that Obama is the main spokesperson for, by the way—that has created a situation where a lot of these dads are absent not by choice. And then he’s going to beat down: well, we gotta do something about these dead-beat dads. No, we gotta do something about the system that is creating this. And in relation to that, it ain’t that we need people to man up, and we don’t need the men to step forward and play their traditional role in society being the head of the household and a role model for their children. What we need are not male role models, but revolutionary role models, female and male—people standing up and saying no more to the brutality and oppression and degradation that this system is bringing down.

And not just on Black people but on people of all nationalities here in this country and around the world. Saying no more to that and connecting with a movement for revolution, a movement that is aiming to end all of the horrors that this system inflicts on people, the violence against women, the attack on their rights, including their rights to abortion and even birth control now. A movement of revolution that will end the horror of the attacks on the very environment of the planet, the massive government spying, the wars for empire, the drone strikes, and all of the rest. That’s what’s actually needed and that actually needs to be brought forward in opposition to this Brother’s Keeper program, and an understanding that what it’s about is actually strengthening and tightening the oppression and exploitation that comes down, not only on Black people—definitely on Black people, but also people around the world of all nationalities.

Two Different Outlooks, Two Different Programs

Revolution: I was talking to some people recently and they were talking about this point in the World Can’t Wait call about “that which you do not resist you will be forced to accept.” They were saying that’s a certain thing that’s going on with these police murders—that there’s a certain way that it becomes the new normalcy, the new terms of things. And that’s part of this question of the month of resistance too—that we actually have to change the terms in society. And then the other point we were talking about is we have to go for what people are thinking: "I gotta get mine and take care of myself"—to "we gotta free the people from this system."

There’s the stark the reality of these two sets of parents of the murdered children (Trayvon and Jordan) being at the Obama speech on February 26th. They played by the rules. There’s also an ideological and even physical enlistment of Black men as enforcers of the status quo. If I remember right, there was a line in the speech like: nothing keeps a kid in line like a father. Ross Douthat actually has this article where he says if you want to do something about inequality you have to restore male right, you have stop the abortions, and stop the birth control and give men an incentive to stay at home where they can be dominant. He literally put that in the New York Times.

Could you say a little more about both the problem and the solution? And also talk about how you see this and its relation to the Stop Mass Incarceration Network? How is that in opposition, in distinction, to Obama?

Carl Dix: That’s a good question and important contrast to make because Obama’s speech is really training people what to think and how to think, how to look at this problem of mass incarceration and all of that. This is not a quote, but here’s the message: “Look, maybe there’s some excesses, but what we’re really dealing with here is people’s behavior problems, that people are not taking responsibility for their lives, and especially Black men are not taking responsibility for their lives.” And Obama says this is the problem that we’re trying to deal with, and our solution is to encourage and give some assistance to these men to step up and play their role in society, which needs to be the traditional male role of head of the family and keeping the women and children in line and in check, and that this is the solution and that if this step is taken it will strengthen America. And I’ve already talked about how you need to look at America and that it is not something that the oppressed need to step up and help strengthen, but in fact they need to be part of a revolution aimed at getting rid of American imperialism. But [what Obama said] is what’s being put forward as a solution.

And the other thing about how people should think about this is that, look, some people have made it through—and Obama had these guys from Chicago as an example of people who have made it through the minefield that the system puts out there in front of them and forces people to go through, and that if more Black men were doing it right, then a few more of them would make it through. And from that the way you’re supposed to look at it is: okay, let’s see if I can get me and mine through, if a few more of us can make it, and in particular can I make it, can those that are close to me and that I care about make it? And, see, this is entirely the upside-down wrong way to look at it. Because you have a system that is grinding people up, it’s breaking bodies and crushing spirits, and it is no solution if you can maneuver a few bodies through that crushing and grinding that’s being inflicted on people. In fact, what’s needed is people saying: no more of this, people standing up and resisting what’s being brought down.

And that is exactly what the Stop Mass Incarceration Network is aiming to do through this call for a Month of Resistance in October. Because more people are recognizing mass incarceration as a problem, they’re seeing it: this is not good. People who are having it done to them, who are caught up in the criminal injustice system, but also people who don’t directly suffer that but who are seeing what’s going on and saying: I don’t want to stand aside, I need to be involved in trying to do something about it. That’s a good development but it’s got to go much farther. People have to be more clearly exposed to the horrible outrages that are being committed on this front, people need to begin to see that this amounts to a slow genocide that has tens of millions of people enmeshed in its web and they need to be moved to the point of standing up and joining an effort to stop it. Millions of people need to be exposed to this reality and many, many of them, thousands of them, have to be moved to being part of standing up and stopping it.

And that’s what the Network has in mind with this call. And that’s why Cornel West and I issued this call for the Network that there needs to be a month of resistance, a month that will include coordinated national demonstrations nationwide on October 22, the National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression, and the Criminalization of a Generation, and something that has thousands of people out on that day. There needs to be a major concert that will have people sitting up and taking notice when they see who’s performing together and that they’re all performing around condemning, calling out, and acting to stop mass incarceration. A statement issued by and signed by well-known and prominent people being published in major publications around the country, panels and symposiums on college campuses, expressions of opposition and resistance to mass incarceration in religious circles—all that and more.

All of it is not worked out yet—we’ve got a basic vision and we’re going to be getting people together and meeting and strategizing over fleshing out that vision and hammering out a plan to build up from now to October. But that’s what it needs to bring forward–it needs to bring forward a sense of standing together and saying No More to these horrors that are being brought down and having a view of not: how do me and mine navigate through all the obstacles that are put in the path of Black people trying to make it in this society, but a view of how do we break through these structures—what do we have to do to get rid of these structures that are holding people back? And, look, what that comes down to is understanding that this stuff is built into the fabric and framework of this system and that it will take revolution–nothing less to end not only it but all of the horrors that this system is bringing down on people here and around the world.

April Strategizing Meeting

Revolution: So Carl, tell me, you and Cornel West and the Stop Mass Incarceration Network have called a meeting in early April, and I’ve heard you say other meetings, besides, but this meeting in early April—who should be at this meeting?

Carl Dix: Well, here’s the deal. The Stop Mass Incarceration Network has looked at the situation and seen a need for a major effort to take the level of resistance to mass incarceration to a new level, a new height, involving thousands of people, as a springboard to ultimately enlist millions in this movement, and that we’re going to work to do that through this month of resistance in October. And we’re taking the responsibility to initiate this and to lead it forward. And Cornel West and I issued the call for this meeting, and we want to bring together people who seriously want to take this movement of resistance to a higher level and be a part of working to do that, fleshing out a vision for it and developing a plan.

And there’s really a lot of people who need to be involved in this process. One, there needs to be young people involved, college students need to be involved in this from the beginning, at the meeting, contributing their understanding, their experience, and then leaving the meeting on a mission to spread the call for October and to build resistance up to October as part of what’s being done in this. High school students should be there with the same thing, bringing their experience into it, and [inaudible] out of it, ready to spread that in all the ways that they would want to do that–armbands days, hoodie days, days when people do stuff on social media, spreading pictures of themselves wearing armbands and hoodies on Instagram and Twitter and Facebook and all like that.

Generally people who are catching hell on this front need to be represented, and in addition to the young people there needs to be family members of people in prison, who played an important role during the California prison hunger strike—they need to be in this meeting. Family members of police murder victims, formerly incarcerated people—all of them need to be bringing their understanding, their experience into this meeting and being part of hammering out the vision for this and spreading it throughout society. We need to have religious leaders and lay people in this meeting bringing their own stance on this, their moral opposition to this, helping to hammer out the vision, and then figuring out the ways that this gets expressed powerfully in religious institutions. It’s gotta be nationwide right from the beginning, people from different parts of the country who’ve come into New York for this [meeting] so that we come out of the meeting with a framework that is in position to operate and spread this nationwide. People who are grappling with the problem of the immigration raids that tear families apart and disappear people–they need to be a part of this, because this has everything to do with the incarceration that’s going down in this society. They need to be there, they need to be in position to spread this and spread it nationwide. Legal people need to be involved in this meeting, people whose arena is the arts and culture need to be involved in this meeting.

Everybody’s bringing their experience, their understanding of this and then being in the position to pivot back and out and spread that throughout society and in the arenas that they function in. And in some of these different arenas that I’ve just talked about, prominent people, people whose voices have impact societywide. Some of them need to be in the room for this meeting, people who can reach people throughout society when they speak up and stand up around a question, people who can play an important role in raising the kind of funds that’s going to be needed. Because it’s going to take a lot of money just to hold this meeting to get this process started which will then pale [compared to] the amount of money that will need to be raised to carry it through to the end. And we gotta have from the beginning people who have the connections and the experience in terms of doing that.

And I guess the other thing I want to say about who needs to be in the room is that Cornel West and I were talking in the last couple of days about this, and we issued a letter. And that letter basically says, look, if you’re a young person, Black or Latino, who’s tired of wearing a target on your back—you need to be involved in this effort and you need to think about coming to this meeting. If you’re a parent who is tired of living in fear every time your children leave the house in the morning as to whether they’ll make it back safely, if you’re somebody who doesn’t experience this but you’re aware of it going down and you hate it and want to see something done about it, well, you’re the kind of person who needs to be involved in this effort. You need to think about coming to this meeting. This is a meeting to get together people who are serious about it, want to do something to stop it, and see this vision of a month of resistance in October that takes the movement of resistance to a whole new level and that makes this something that millions of people in this society are seeing as a horrific problem and they’re seeing determined resistance to it that involves thousands. If you want to bring that vision into being and make it real, you need to be at this meeting.

On Choices

Revolution: A lot of people say to you, though, that you criticize Obama for saying “no excuses,” but you’re just making... you know, look, people make bad choices. And you’re just making excuses for those people. Don’t people have to make better choices? What do you say to that?

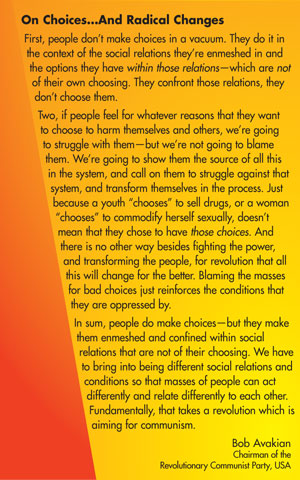

Carl Dix: Well, I think there are two things I want to say to that. The first is that Obama and people like him make all kinds of excuses for this goddamned system and the shit that it does to people. And that’s the first thing that people who want to pose this question of excuses and choices need to get to. But then here’s the other thing. On the choices that the masses of people make and how to look at that, for me the best way to express it is to read this quote from Bob Avakian: “On Choices... and Radical Changes”:

First people don’t make choices in a vacuum. They do it in the context of the social relations they’re enmeshed in and the options they have within those relations—which are not of their own choosing. They confront those relations, they don’t choose them.

Two, if people feel for whatever reasons that they want to choose to harm themselves and others, we’re going to struggle with them–but we’re not going to blame them. We’re going to show them the source of all this in the system, and call on them to struggle against that system, and transform themselves in the process. Just because a youth “chooses” to sell drugs, or a woman “chooses” to commodify herself sexually, doesn’t mean that they chose to have those choices. And there is no other way besides fighting the power, and transforming the people, for revolution that all this will change for the better. Blaming the masses for bad choices just reinforces the conditions that they are oppressed by.

In sum, people do make choices—but they make them enmeshed and confined within social relations that are not of their choosing. We have to bring into being different social relations and conditions so that masses of people can act differently and relate differently to each other. Fundamentally, that takes a revolution which is aiming for communism.

And again, that’s a quote from Bob Avakian.

International Calculations of the U.S. Rulers

Revolution: Earlier you mentioned that Obama had said in his speech that when we strengthen young Black men, we strengthen America. Do you feel that there’s any international calculations that are involved in initiatives like this or in a lot of the lip service that’s being paid, for instance, to changing the sentencing laws?

Carl Dix: Look, the U.S. goes around the world lecturing countries on violations of human rights, uses human rights as a justification for intervening, invading, enforcing its will all around the world. And, as it became in the 1960s, it is a question they encounter and run into as they’re doing all of this… that people point to: well, look at what you guys are doing. Look at the fact that your country has 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent, proportionally, of people in prison. Look at the racial disparity of who’s in prison, which is the greatest disparity racial-wise when you look at the numbers of Black and Latino people who make up the prison population–it’s the greatest racial disparity around the world, according to recent studies. So this is something that they do run into and this pulls the covers off of any legitimacy they might have in talking about: well, this country is a human rights violator or that country is a human rights violator. Because it gets pointed to: Well, what is the U.S. doing? The United States is torturing 80,000 people in prison, holding them in long-term solitary confinement 23+ hours a day, confined to very small spaces, denying people any human contact while they’re held in solitary confinement, no visits from family members, not even allowing them to have contact, to meet with their lawyers, putting them in solitary confinement arbitrarily with no process through which they could challenge their being placed in that confinement–and doing it for indeterminate periods of time. There are people who have been in solitary confinement for four decades in prisons across the country. And scientific studies have found that confinement in these conditions for more than a few weeks can drive people insane. Yet there are people who have spent decades under these conditions. And the U.S. refuses to recognize these international studies and the designation of long-term solitary confinement as a form of torture. But that’s what’s going on.

In relation to that, you’re getting Obama speaking out about how we have to do something about the incarceration rate, we have to do something about the way in which it targets Black people, other oppressed people. You’ve got the U.S. attorney general talking about it too. And that’s all designed to, again, speak to the international sense of the U.S. as a human rights violator and a country that is carrying out horrific abuses on sections of its own population, and also to lure people back into the folds of the channels of the system here in this country.

But then when you get down to the reality… I think they commuted the sentences of eight people who were in jail for the rest of their lives for possession of banned substances. But then there are thousands of other people in that situation who recently became part of a class-action suit to get their sentences reduced because there was a 100 to 1 ratio for sentencing, which means 5 grams of crack cocaine got you the same penalty as 500 grams of powder cocaine. Well, they reduced that disparity to 18 to 1. Still a disparity that has no scientific, medical, or legal basis—but they reduced it to 18 to 1. And that 18 to 1 reduction means that there are thousands of people in prison who if they were sentenced under that instead of 100 to 1, their sentences would be over and they should be released. And that was the basic premise of this class-action suit that thousands of people in prison were part of, and they did not get out because Attorney General Eric Holder’s Justice Department went into court and blocked it. What they did is they blocked the actual court case and then Obama said there needs to be legislation to address this problem, which means Congress will have to pass a bill to make this happen. And Congress these days does not pass very many bills and is highly unlikely to pass such a bill. So effectively they have blocked these people from being released from prison.

What's Happening with Black Students

Revolution: One of the ironies that people have commented on in the speech was that Obama is doing this in the wake of the anniversary of the murder of Trayvon Martin and he’s proposing these solutions to this problem that is an internationally recognized outrage. And yet the very solutions he’s proposing of strengthening fatherhood—in both the cases of Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis… this young man who was killed was living with his father and was in high school and “playing by the rules.” And I wonder if you could comment on that and then also what’s going on right now with Black college students. It seems like there’s important beginnings of protest in different arenas but there’s also this... what part of the protest is being driven by is that there seems to be an actual way in which over the last decade Black students, Black college students, are being pushed out of the major schools.

Carl Dix: There is this thing that, well, the problem is that people aren’t acting right, they’re not playing by the rules, they’re not living their lives in ways that would allow them to make it in this society. And then you look at what’s being proposed in this Obama initiative and then you look at the situation of Jordan Davis and Trayvon Martin. The problem wasn’t that there was no father in their lives. I mean, Trayvon Martin was with his father when he was murdered by George Zimmerman. Jordan Davis’s father was in his life—it wasn’t a thing of there was an absent dad and a wayward youth. Both of them were in high school, on a track to graduate, and Trayvon was an athlete—he played football on the high school football team. So you got people who were playing by the rules, who were doing things right and none of that saved them when they encountered the racists who took their lives.