Down for Revolution:

An Interview with Clyde Young

An Interview Reprinted from the Revolutionary Worker (now named Revolution)

October 6, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

In this interview, the RW talks with Clyde Young [formerly known as "Comrade X"], a leading comrade in the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA. His life journey—as a Black street youth coming up in the early 1960s, through two prison rebellions, and up to the present—is of definite interest to sisters and brothers who are looking for a way out of this racist and downpressing system. The interview originally appeared in RW issues #569-573, August 26 – September 23, 1990.

Part 1: Coming Up: Fried, Dyed and Laid to the Side

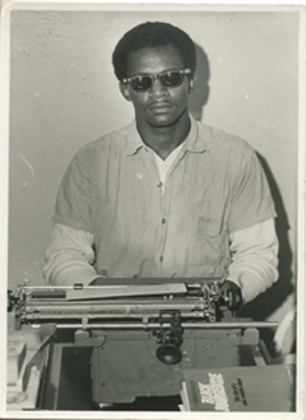

Typewriting in prison, Michigan City, Indiana, circa late 1960s.

RW: You spent a lot of time in prison when you were coming up and you became a revolutionary in prison—and a revolutionary leader. So we'd like to get down on that whole story. And we know that your experience can shed some light for the brothers and sisters—who are right now up against some heavy fire from the powers-that-be—on why they should become revolutionaries.

There's some lines in the rap by Public Enemy "Don't Believe the Hype" that typify the situation for Black youth today:

"About the gun...

I wasn't licensed to have one

The minute they see me, fear me

I'm the epitome—a public enemy

used, abused without clues

I refused to blow a fuse

they even had it on the news

Don't believe the hype."

How does this song relate to your situation when you were coming up in the 1960s?

Comrade X: A lot of what's captured there speaks to what it is for Black youth and other oppressed youth coming up in this society, not just now, but when I was coming up too. One of the main differences is that now the shit is a lot sharper. Public Enemy has this picture on the front of their album—a Black youth with a target on his chest. And a lot of what characterizes the situation today is that the powers are tightening up their whole state apparatus and in the name of the war on drugs actually conducting a war on the people and the youth. That's the character of it.

Malcolm X used to talk about that there was minimum security and maximum security. He'd be talking and be saying he had been in prison and he'd tell people, "Well don't be surprised, you're in prison too—it's a question of maximum versus minimum security prison." But increasingly from what I can see, the distinctions are getting blurred. I mean, when you have people getting stopped like these youth stopped in Boston and strip-searched out in public and shit—and housing projects being turned almost literally into prisons—some of the distinctions between the maximum and the minimum is beginning to get blurred.

So things are a lot sharper. And even in terms of the reaction of the youth I think, as is somewhat captured in the lyrics of Public Enemy and some of the other rap groups, there is a rough edge or a hard edge that didn't exist quite in the same way when I was coming up. But there's a lot that's similar in terms of going up against the other side. Like that point from Mao about how the oppressed fight back and in fighting back they search out for philosophy and I think that speaks in a lot of ways to what my life was like.

I can remember when I was arrested for the first time was when I was nine years old. It was a situation where I was in a 5 and 10 cent store—I don't think they even have those anymore. I stole something. At this time I can't even remember what it was but it was something really petty. And I was arrested and taken downtown and put in jail. I was in a cell by myself, but I was actually in the jail for men—when I was nine years old. And they held me down there and tried to intimidate me—and succeeded, at that age—until my parents came and got me. This is the kind of thing that happens growing up Black in this country. Had I been white it probably would have been resolved a lot differently, just by either taking me home or telling me not to do it anymore. But in my case, right from the beginning, it was resolved in a very harsh fashion.

From the time before I was a teenager up until I was a grown man way into my 20s, I was repeatedly involved in various contradictions with the state and being put into prison. And if you put together the crimes supposedly that precipitated that, they were all very, very minor. But I'll try to get into some of that as we go along.

The first time that I was really convicted of something was a very minor and petty offense—I stole a pound of hamburger. At the time when I was coming up we were very poor, so I had a scheme that I would work. My mother would send me to the store with a dollar or two, and I would steal what she wanted me to buy, and then I would keep the money to have some spending money. And this one Saturday—I can remember it very vividly—I went in to do that and I got busted. And once again, right away they took me downtown. But this time it wasn't even a question of my parents coming to get me. They put me in a juvenile detention center for a couple of months and then I was put on probation. This was when I was 12 years old.

By the time I reached 13, I had been arrested again for shoplifting and riding in a stolen car, or stealing a car, which was a violation of my probation of the previous incident of stealing the hamburger. So I was sentenced to the reform school (or boys' school) for a period of time. Actually the way they did it at that time was they sent you there indefinitely until you were 18 years old.

At that time I was not really conscious of how to understand all this. There were some ways I knew that this shit wasn't right, some things were wrong, and I had some sense of how Blacks were oppressed. But it wasn't any kind of put-together understanding that I had at that time. So I went off to reform school for nearly a year, and I would say that through all of this I was beginning more and more to get an understanding of some things.

RW: A lot of times the youth are caught up in it but they don't see that it's the whole system coming down on them.

Comrade X: Of course I can see it much more clearly now looking back. At that time when I was growing up, in the South people still had to sit in the back of the bus and were subjected to all kinds of Jim Crow shit. And that was not only true in the South but also in the North. In fact, Malcolm X made the statement at one point that the South began at the border of Canada. In other words, it was the whole country, because in the North some of the same stuff went on, but it was more disguised. Cuz I can remember even where I lived, which was in the North, some of the drug stores and restaurants, Blacks couldn't sit at the counter—the same way it was in the South. But the whole system, the whole penal system and the whole state apparatus, was set up in such a way so that everything was aimed back at the oppressed people. And this is the same kind of thing that you see coming down on the youth today in a lot of ways.

You'd go in to see your probation officer or the social worker, and the interviews a lot of times would consist of, "Were you fed well, did your parents abuse you?" Here was a situation where we were very poor and a lot of times it was a question of not having anything to eat of having fuel or coal. I would have to go out and find wood so we could stay warm, and eat sugar sandwiches and shit like that. In other words, we didn't have shit. This was before there was a lot of openings in the '60s where people began to get into better-paying jobs. And instead of that being looked at as the source of the problem, the authorities, the social workers and such, would ask you, "Well, do you think you're a kleptomaniac?"

And ultimately I came to see it as a bigger problem—that capitalism and imperialism was the source of this and the whole character and nature of the oppression of Black people in this country, having been brought here as slaves, forced into slavery, and then even after slavery being forced into a state of virtual slavery in the South. And all of this had everything to do with the contradictions that I was facing as I was coming up as a kid.

RW: What happened when you went to boys' school?

Comrade X: When I went to boys' school it was a very regimented type of situation. The boys were in cottages which were like small houses. But first they kept you in what they called "quarantine" where they oriented you to the rules and basically began the process of breaking your spirit, which is what it was all about. I can remember being in quarantine. The floors were just spotless, you could almost eat off of them. And largely what we spent our time doing was mopping and waxing the floors and walking around with pieces of cloth under our feet so we wouldn't scratch the floors. We couldn't wear shoes or anything.

It was also very segregated. The Blacks were in certain cottages and the whites were in certain cottages. And the whites, to the extent that this could be the case, had more privileges than the Blacks. When I got out of quarantine I went into this cottage—and everybody was going into what we called the scullery—I guess it's some English word for the kitchen—and I was the last to go in. As I walked past the cottage supervisor, he said something to me and I said, "No," and all hell broke loose. He knocked me down, threw a chair on top of me, and hit me with a chair, pulled out a whip and whipped me, and all of this was because I didn't say, "Yes SIR."

They only let you wear your hair so long, so in order to keep your hair long you had to put on a woman's stocking. You'd take it and put it on your hair so that it would be pressed down and it wouldn't be too long. Otherwise they'd make you get it cut off, because when you first go in there it's just like the army. They cut your hair off, it's very regimental, very humiliating. They make you march in formation and say the Lord's Prayer and pledge allegiance to the flag and all this kind of regimentation and strict control over everything you did. There were certain areas in the cottage where you could talk and where you couldn't talk and if you were caught talking, there were snitches and what not that would write your name down. And if your name came on the list then you would get the strap. For all this talk about child abuse, they would make you lean over a chair and make you pull your pants down and beat you with a razor strap. For talking in the dining room you'd get 10 licks—but if you let go of the chair before the cottage supervisor got to 10 then you had to start all over again, so this could go on for quite a long time. It was just very fascistic in that kind of way. And that was not all that inconsistent with the atmosphere in the country in the '50s and early '60s—that was the way things were carried out. Later on when I got out and got a little older and came back, I rebelled against some of that—including challenging the cottage supervisor himself.

RW: Where were most of the guys from, what kind of background?

Comrade X: Overwhelmingly proletarians. A lot of the people I met in reform school—and these people came from all throughout the state—later, when I was older and went to prison, there was the same people. This was the track you were on and the people you met there were frequently the same people you met when you got to prison later on in life.

RW: Some people treat the whole question of crime in the inner cities and youth gangs like it never existed before, when in reality the oppressed people have always been in a situation where it was allowable to brutalize each other, but crossing that line to fight the system was something different.

Comrade X: That's definitely true. In fact that was a point the Chairman1 made in the interview about the Black Panther Party. Where I grew up it wasn't like there was organized gangs as such, but it was more that there was turfs, which is more or less the same. It was the East side versus the West and the North side versus the South. If you went on the wrong side of town then it was your ass. Of if you went to a party on the wrong side of town and you stepped on somebody's shoe or something, these minor kind of things like this, it very often went over to violence. And in some other places like Chicago, not only did they have gangs, but they were like empires. Thousands of people were in them and in fact you were forced into them. So it is definitely the case that this has existed for a long time.

And also, too, this whole point of it being "allowable" in a certain sense if you are doing it to one another. It is different than if you even step out and start committing violence and violent crimes against whites, to say nothing if you begin to go over to become a revolutionary and start attacking the system. Then there is a whole different ball game.

RW: Getting back to your story. Clearly when you were in the boys' school and they ran this whole discipline trip on you, it did not work. It did not achieve the results that they desired.

Comrade X: No, it did not. I would have to say before I began to take up revolutionary ideas and especially before I began to take up Marxism-Leninism-Maoism2 that they could confuse you. They never really succeeded in breaking me and a lot of the people that I grew up with, but they could confuse you in terms of your understanding. I used to think, "Why am I getting into this shit all the time? I don't want to get busted all the time but here I am. I made a promise to myself that I wasn't going to get into this situation again, but here I am again." In other words, there was a whole thing of making you think it was really you that was the problem rather than that there's a whole system and the whole setup. Like when I was young and used to shoot dice, they used to have different kinds of fake dice they could put in on you. And that's the way this system is: the dice are loaded. They are shooting loaded dice against you.

It wasn't like I really had it all together in terms of why all this shit was happening this way. But like a lot of youth, I not only had dreams but I also thought about why shit was this way and why it was that people over here were poor and people over there were just born rich. Where I lived, on this street and this whole area was all Blacks and extremely poor, but then not far away from where we lived it was like a whole rich section of town. And you'd think about these things. Why was it that way? Why was it that people had to go hungry and go without the basic essentials of what it takes to live? And on the other hand, they were mocked and surrounded by all this wealth. That was a thing I did ponder when I was a kid before I came to understand fully what this was all about.

RW: Who were your heroes?

Comrade X: As I grew older I wanted to be a hustler, I wanted to live by my wits and I wanted to be in the streets. I didn't see much of a future in working like a slave eight hours a day like I'd seen my parents do and other people around me. It just didn't seem to be heading anywhere. It didn't have any attraction to me. What attracted me was this other kind of life, where you are more in the streets and living by your wits and hustling. And that's the sort of thing I got into.

When I was coming up, a lot of the people that I admired were the older "brave elements"—the brothers who stood on the corners and wore their pants high up. They used to have a style where you wore your pants all the way up to your chest. And they wore their Kadies and they had their switchblades. It was just a certain style of going up against things, not in a conscious way, but there was a certain style in opposition. And it was what it meant to be a youth at that time. Those were a lot of the people that I admired and later ended up in prison with—the "Brother Russells."

Brother Russell, who himself is dead now, was one of the people that I admired and looked to as a "role model" as opposed to somebody like King. I was reading recently this tale about Stagger Lee, and he reminded me of Brother Russell. He was one of the "brave elements" that hung out on the corner. Brother Russell got into prison because he was involved in a crap game and somebody made the mistake of slapping him and he ended up in prison for murder. Brother Russell was not the type of person that you'd want to slap, that was like a serious mistake and ended up to be a fatal mistake. So Brother Russell ended up going to prison and ended up in prison when I was there. By that time I had become a revolutionary and I became a different kind of "role model" for him, so it was kind of a switch.

Those were the kinds of people, the people who had their hair fried and dyed and laid to the side, with a part not too wide. Back then, it was like a process. There was a certain edge to that style that was not respectable, that was "in your face." Black people who were respectable or who were in entertainment might wear a process, but to wear your do-rag and to have your do-rag in your pocket and that sort of thing, there was a certain unrespectable edge to it that sent the other side up the wall.

They were the outlaws. They would wear their outrageous clothes and they would stand on the corner and they would croon and those kinds of things. And that's who I admired and who I wanted to model myself after. And later it was me that was out there like that.

RW: In opposition to the treatment you received, you developed a certain contempt for death which is similar to the attitude in the lyrics of the NWA rap "Fuck tha Police":

"...They have the authority to kill a minority.

Fuck that shit, cuz I ain't the one

For a punk motherfucker with a badge and a gun

To be beatin' on and thrown in jail."

Comrade X: I think early on a lot of this contempt for death and a lot of the way the stuff came down was against one another. There was this whole thing about who was bad on the corner and you weren't gonna let anyone get the better of you.

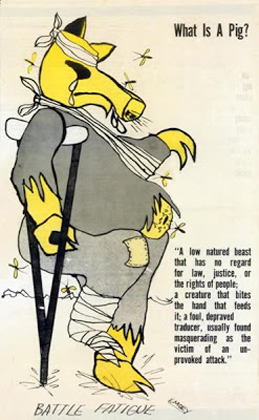

From the Black Panther Party newspaper

But there was also contempt for the pigs. When I first began committing robberies and burglaries, I would go into a place and start burglarizing it, and just in terms of the fearlessness I had of the state, I would go in and start cooking myself a meal. Like I figured they had the same thing that I had and I probably had more heart than they did, so if they came I was ready for them. And that was the spirit that I had and in fact a lot of the youth had, and it's not all that different than what exists now.

I was just not long ago rereading some of Malcolm X, and he talks about when he was coming up—this whole thing about "face." It's like a street code and also it's a similar type of code in prison. In other words, the way he puts it in his book is that for a hustler in our sidewalk jungle world, "face" and honor were important, no matter. No hustler could have it known that he had been hyped, meaning outsmarted or made a fool of, and worse a hustler could never afford to have it demonstrated that he could be bluffed, that he could be frightened by a threat and that he lacked nerve. It just basically comes down to machoism—that you can't let people do anything that would offend your manhood or offend your face. And if that happened then you had to go down, or you weren't down.

That was a whole part of existing on the street, is that you had to have that heart, have that nerve, not be able to be backed down by someone else if it came to a confrontation. That's part of the whole psychology of the streets that goes on, and some people from the '60s who are getting down on the youth today forget that. This is not something that even just existed in the '60s, Malcolm is talking more back in the '40s, that same kind of code of the streets and also something that exists in prison.

RW: Looking back on it, you said you see positive and negative things in it. What do you mean by that?

Comrade X: On the negative side, what can I say: that street code or prison code has a lot of individualism mixed up with it—to say nothing of machoism and male chauvinism. I've been there, I know what it is all about. And I've come a long way in breaking with that kind of outlook. That's the Man's way. Our way is: "Brothers rising up with sisters, strong, proud and with equality: that's our way, the way we all get free." The youth today (and here I'm speaking especially of the brothers) have to be struggling over that kind of thing, that kind of macho outlook. The revolutionaries have to have a first-string orientation and all-the-way revolutionary politics in command, uniting with the anger of the people and striving to direct it in the most powerful way at this cesspool that they call "the greatest system on earth." And we got to make that part of preparing to bring this system down. As we've said: "While we're battling them back, politically like that, we got to make this part of getting ready for The Time—and it can come soon—to wage revolutionary war."

On the positive side, when these youth begin to become more conscious and that same fearlessness and anger and contempt for death begins to be directed at the system and the powers-that-be, then you have a whole different ball game. All that is a necessary part of what we have to do in bringing this whole thing down, you need that, you need that spirit. You obviously need a lot more than "heart" but you do need that. So that's how it divides into two. On the one hand the way it plays itself out in the streets and in prison and all of that is a reflection of machoism and gangsterism and that sort of thing. But on the other hand, there is the situation that when that attitude gets transformed through the leadership of a party and when people begin to take up the science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, it's not like you lose that same fearlessness and that same hatred—it's just tempered, if you want to put it that way.

I can remember having a lot of hatred, but it was not focused and not directed and oftentimes it would be focused in the wrong way and the wrong direction, but it's not like I've lost that hatred and anger. I still have a monumental anger and a monumental hatred for imperialism, as the song says, "deep in my heart I still abhor 'em." And after all these years, I still don't fear them. So the question is how do you lead that, how do you have a first-string orientation?

When I was coming up, there wasn't a party, there wasn't a party that was based on Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, that could give some direction. And later as I got into my teens there was the Black Panther Party which played a vanguard role and made a tremendous difference. Today there is a party, our Party, that is preparing to make revolution in this country as a component part of the world revolution. There is a party with the line, leadership and battle-plan to lead things all the way this time around.

A whole generation of youth came forward in the '60s who wouldn't be intimidated and weren't too impressed with the power of the state, and we need to bring that forward again and take it all the way this time.

Part 2: Burning Down the House

RW: The rap "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" tells the story of a brother who refuses to join the army and ends up in the joint. You almost joined the army once. What happened to change your mind and how do you see it now?

Comrade X: There was a time when I was under the gun. I knew that it was a turning point in my life. I had been repeatedly into jails and I had just recently went through a whole situation with a stolen car where I was being chased through woods and shot at and dogs were after me and all of that. And I knew that there was a very good likelihood that within a short time I would be dead or in prison. That was the terms of things. There wasn't any other terms I was looking at.

A lot of people in my family tried to talk to me. Especially some of my uncles tried to talk to me and tell me to "slow down," that I was living "too fast of a life." They could see that I was up against something and I was headed toward some kind of climax that wasn't going to be real great.

I was not so politically aware at that time. So I was going to get into the marines, become a man, that sort of thing. I was desperate.

It was one of my uncles... I don't think he actually had fought in the Korean War himself, but he had been in the military. He caught me on the street corner, which was at that time where you could catch me. And I was like, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, I gotta go man." But he was persistent and he struggled with me. He was coming from an orientation of, "Why would we go and fight and die for these people, it ain't our war." And his whole point was, "When people go over there, it's just a fight to get back, it ain't like you got something to fight for."

So somehow, someway—even though I was moving fast then and not really prone to listen—he got through to me and changed my mind.

RW: This was during the beginning years of the Vietnam War?

Comrade X: Right. It's kind of ironic, because here I was into all this shit with the state and had pretty much grown up in prison institutions, but at the same time I was caught in a trap of their ideology—you become a marine and go overseas and all that and you become a man. And that's the sort of thing that had floated around in my family from others who had gone and fought in Korea and some of the other wars. So I felt that this was my way to get on a different track. But as it turns out, a few months later I was in prison, which in the final analysis was a much better resolution of the contradiction.

RW: Some people would be shocked to hear you say that you thought being in prison was a better resolution than being in the army.

Comrade X: In hindsight, in looking back, yes. When my uncle was struggling with me not to go in the army, he was struggling from a Black nationalist position. But later on when I got into prison and as I evolved in terms of taking up revolutionary theory and practice, I became an INTERNATIONALIST. There was a certain sense in the '60s, a certain aligning of oneself with the enemy of your enemy. So there was a whole thing of identifying with the struggle that was going on in Vietnam from the standpoint of the Vietnamese people and identifying with the struggle that had gone on in China and in Korea. Some of the things that were really exciting and liberating to me when I was in prison was studying about how the U.S. had gotten their ass kicked in Korea and how they were getting their ass kicked in Vietnam. Here was a country with peasants who were able to defeat one of the most powerful countries in the world. That was tremendously inspiring. So I think that going into prison was in a certain sense going into school for me. I had been schooled through my life and my life experiences. But there I was introduced to revolutionary ideas. And that's why I would say looking back on it that it was a better resolution to the contradiction.

RW: This was around the time of the Detroit rebellion when you were sent to prison for 20 years. How did that come down?

Comrade X: I was convicted for armed robbery, and in the course of it there was a shootout with the police. No one was hit, but my trial came up against the backdrop of the Newark rebellion, and more immediately the Detroit rebellion had occurred—and the whole atmosphere was charged. I was aware that these things had happened, but I wasn't aware of the overall impact of them. But even in my own trial it had some impact in terms of the jury. It was basically an all-white jury, and they didn't like my arrogance, they thought I was too uppity. This I learned later, through my lawyer.

It came out in the summation of the prosecutor that I had this attitude problem. It wasn't like the Detroit rebellion itself was brought into the trial, but the way it came out, I felt, was this whole reference to being uppity and being belligerent and in the final analysis being rebellious in the way I presented myself in the courtroom. And they gave me 20 years.

RW: So you were sentenced for being part of the oppressed people who had dared to rise up?

Comrade X: Right, at that time I wasn't all that politically conscious but that's the way they viewed me.

RW: How did you get caught? You must remember that day...

Comrade X: All too well. It's funny. Two of my friends and I, we all got busted together. But I had money in my pocket, so I got out on bond and I went to get some money to bail these other guys out of jail. At that time I wore like a gangster lid and a big dark overcoat, and I could have had some work on my tactics, because I went into this depressed white area, dressed up this kind of way, to stick up this place. And it just so happened that some pigs happened to see me going in there, so they circled around and came back and saw the robbery in process. And there was a shootout and they managed to apprehend me at the spot.

RW: What were some of the early incidents you remember when you started to have more of a revolutionary awareness?

Comrade X: Well, when I went to prison, just to give you a sense of this whole attitude of fuck you, my whole orientation when I got 20 years was, "I'll do 10 of those standing on my head and the other 10 getting back on my feet." That was my attitude. "I'm young—fuck you."

I was beginning to put some things together that had been occurring to me throughout my life on what the fuck was going on, and one of the things that began to strike me was how many oppressed people were in these prisons, both Black and white, that if you had money you were able to avoid such things, and that it was overwhelmingly proletarians that were sent in there.

The robbery that I was involved in netted $140. And here I was marching in with 20 years. The deck was stacked, so to speak.

When I went in, there was this one guy I had been in jail with for a period of time, whom I had grown up with, and by the time I got to prison, he was already into Black nationalist politics. So he tried to turn me on to it. But I kind of kept my distance. Then there was an event that had a big impact on me and began to change me.

A year or so after I was in, some of the more politically conscious prisoners—who at that time were into revolutionary nationalism—they had a protest. I can't even remember what the demands were. I was in a dormitory situation and I was able to look out my window and observe all this.

These guys came out and they had some demands that they were going to present to the warden. And the prison authorities immediately came out with shotguns and surrounded them. There was one Black guard but they wouldn't give him a shotgun, they gave him a club. He was like a token lieutenant if I remember correctly. And the prisoners were doing a lot of agitation about that and telling him, "Look at you, they won't even give you a gun," and it was a very sharp experience for me. A lot of times in prison, that's what happens, when you protest, right away they bring out the guns and they use 'em.

So my fear was that they were just going to blow everybody away. Things went back and forth for an hour or two—a very tense situation—where the prisoners clearly weren't going to give up, but at the same time it seemed like they were just going to get massacred. Ultimately it got resolved in a way where nobody was killed and they just put everybody on the buses and transferred them out to the state prison. But it had a very big impact on me as to the courage of people to do that and the anger they had that they were willing to risk getting killed for what they believed in. It created an interest in me for where they were coming from.

So that's when I began to start reading some things. First Malcolm, the Autobiography of Malcolm X and Malcolm X Speaks and so forth. And in a very intense period of about a year I went through a lot of changes. My Nation of Islam stint lasted only a couple of months and it wasn't long after that that I turned to an interest in the Black Panther Party.

RW: What was the turning point where you first started to consider yourself a revolutionary?

Comrade X: Within a couple of years after I was in prison, I would call myself a REVOLUTIONARY. I had become familiar with some of the most advanced revolutionary leaders and thinking in the country at that time. I had studied and become aware of the Black Panther Party, and I would have given anything to be right there with Huey and Bobby and all of them when they were facing down the pigs. It was very difficult to be in prison at that time, you know. So I got into the Panther and through the Panthers I met Mao.

I had also tried, at that early stage of my development, to read things like the Communist Manifesto, but it was just over my head. Mao was something that I could really grab ahold to. I continued to try to struggle with things like the Communist Manifesto and later I got into much more difficult things. But I was really into Mao and I could relate to some of the ways the Panthers were promoting Mao and also to some of what I had learned about the Cultural Revolution in China. It's not that I could get a full understanding of the Cultural Revolution from where I was sitting, but I was really inspired and excited by what I learned of it and heard of it. You know, people throughout the whole world, including people in our international movement, a lot of us were brought forward by that whole Cultural Revolution and Mao in terms of becoming revolutionaries and taking up the science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

RW: Were there certain individuals who played a key role in the revolutionary movement in the prison or was there a group? How did that come down?

Comrade X: At the time in prison, people would get together in groups and collectives and study. There was a core of people who had more revolutionary consciousness and we would study together and work out together. What we envisioned in that period was that there was going to be a REVOLUTION. And we were going to be READY. So we were studying and we were training physically and all of that.

Then at one point some Panthers actually came into the prison, and that was quite an experience in terms of beginning to get more of a sense directly of where the Panthers were coming from and what they were all about. I can remember when they came in, one of the things that happened. In the school there was a mimeograph machine and these Panthers were instrumental in the writing of a leaflet, several pages long—it was more like a propaganda tract. It was hot—it had pictures of pigs in it, the kind of stuff that Emory Douglas used to draw. And we ran it off and distributed it. And the pigs had a fit, they had a heart attack.

One of these brothers had been in the military, so one of the revolutionary things we did was drilling. People would be out on the recreation yard and they'd be drilling, marching up and down in formation. And this is something the prison authorities didn't like at all, they didn't tolerate it at all. The irony is that previously, the guards were forcing us to do it—going back and forth between various places in the prison we were forced to march in formation. But when we began doing this on our own for different reasons and different purposes, they weren't too happy about that. So there were orders that we couldn't do that, that we couldn't drill. There was also another thing that we used to do for recreation a lot of times—instead of playing basketball, we would sit out on the recreation yard and study. And that was another thing that was forbidden. So there was all these kinds of repressive measures that were going on. And they ended up putting those Panther brothers and some others in solitary confinement for some of their revolutionary activities.

This was in 1969. By that time I had developed into a revolutionary and a revolutionary leader. And the locking up of these Panthers in solitary basically precipitated a rebellion in the prison.

RW: Tell us about it.

Comrade X: It sort of played itself out over the course of two days. The first day we sat down in the prison yard and submitted some demands to the warden. The warden was going to review them. And if these prisoners weren't released from segregation, we had our plans. After we presented these demands to the administration and they said they were going to take certain steps to release these brothers and deal with the other demands we had presented to them, we basically dispersed. But at the same time we were very skeptical that this stuff was going to get resolved. So that night we began making our backup plans, so to speak. We were trying to figure out how could we really hurt 'em if they didn't release the brothers like they said they were gonna do.

On the second day after we had submitted our demands to the prison authorities, they said they would consider releasing these prisoners who had been put into segregation. This was the central demand that we had. There were some others about conditions and what not, but really the central one was the repression of these prisoners. I wrote about this in an essay a few years later while still in prison: "By the time we were released from our shelters for recreation that day, most of us anticipated a confrontation with the prison guards but few if any anticipated the tragic consequences of that confrontation. Before we assembled on the recreation yard we received word by way of the prison grapevine that the prison officials had not acted in accordance with their promise to release two of the brothers from administrative segregation. Instead they had placed the brothers in the hole." Segregation is a situation where you are confined to a cell 24 hours a day except for showers and what not. And these cells are separated off from the general prison population. The hole is like when you are put in there you don't have any blankets or any bedding, you just sleep on the concrete floor and it's dark. So they had been put in the hole. The other brothers had been sent to the state prison, as had been agreed.

I wrote: "Frustrated and angered by the treachery of the prison officials, approximately thirty of us decided to burn down the prison's furniture factory, as had been planned on the previous day. Although the furniture factory is the source of a considerable amount of the state's income, prisoners who work there are paid a meager salary of approx. 15 cents an hour. Therefore we felt that the destruction of the furniture factory would constitute a powerful blow to the bureaucratic state and the 'correctional' officers who were responsible for the oppressive conditions which then prevailed at the prison."

So that was our orientation.

RW: Do you remember that day, could you describe it?

Comrade X: I remember it very vividly. It was very tense when we came out of our cells that morning, like you didn't know what was going to happen. You knew that something serious was going to happen, but you didn't know what. We were confronted with the prospect that many of us would probably be dead. That was the way it was. And there was tremendous anger. Things had mounted up and locking up these prisoners who we saw as our leaders was like the culmination of a whole number of things.

So when we went out that day, the plan was that some people who were working in the furniture factory, they were going to supply the liquids that were necessary. And some others of us were going to come into the furniture factory and carry out our plan. What happened, though, is that we were repelled. We got shot at from the guard tower and we weren't able get in and to carry out our plan. So we went back to the recreation yard. Several guards came out armed with shotguns with double-ought slugs in them and they surrounded the perimeter of the recreation yard. The prison authorities ordered everybody to leave who wanted to leave and there were about 450 prisoners who left. There were 212 of us left behind. One of the lieutenants ordered a Black guard, like a token sergeant, who was out there, to leave. He was unarmed. He had promised us that we wouldn't get shot. So the lieutenant told him, "Well, walk around the corner and you won't see it." All the guards remaining behind were white.

We were overwhelmingly Black on the drill ground, with two white guys and one Chicano. And there was something that I learned in that particular battle in terms of uniting all who could be united against the enemy. Because we hadn't succeeded in doing that. In other words, it wasn't like the white prisoners couldn't have been won over—at least some of them—to what we were trying to do, but there hadn't been sufficient efforts to reach out to them to do that.

I can remember thinking at that time and I'm sure a lot of other people were thinking, "This is it." There was a good possibility that we could lose our life, but it was like we had entered onto a continuum from which you couldn't really turn back. We had thrown down with the prison authorities and we were determined that we were going to see this through. We weren't going to turn back even at the risk of being shot or killed. So it was like a real heavy situation. It's kind of hard to put it into words, the tension that we felt. But at the same time there was a certain amount of strength we all felt too, that we were standing up to these motherfuckers and we weren't going to let them intimidate us even though they had their guns and what not.

The guards surrounded the drill ground and I can't remember the exact words, but it was something along the lines of "You niggers have five minutes to leave." So we said, "Fuck you, the five minutes is up, we're not going to leave." And, from what I can remember of the sentiment, it was like that point Lenin talks about in his writings about those times when the oppressed have "contempt for death." That's what we had... utter contempt for death.

It was clear that some of us could likely die, but we were determined that we were not going to back down, that we would see through what we had set out to do. It wasn't like we had this Martin Luther King "sit down and turn the other cheek" kind of thing. We were just fucking angry, and at the same time it was like a tactical mis-assessment on our part that because we were not engaged in any violent acts, their hand would be stayed, that they wouldn't actually kill us. But that was like a really violent introduction to what these people will do to you.

After the five minute period was up, they opened fire on us. We were on a volleyball court. It was like a fenced-in recreation yard and the volleyball court was like five or six feet from the fence. The guards were immediately in front of us outside the fence. And they had shut the door to the fence and stuck their shotguns through there. And some of them were pumping and shooting so fast that one of their guns began to malfunction, they were so anxious to shoot.

But one prisoner just wouldn't sit down. He stood with his Black Power fist in the air and he didn't sit down until they shot him down.

So I learned more from that than I learned from many books about the nature of the enemy at that time. Two people were killed and 45 were injured. The brother who wouldn't sit down was not killed, but he was seriously injured.

So when you enter into these things, it's like Mao talks about—everybody has to die sometime, but your life can be as light as a feather or heavier than Mount Tai. That's the way you felt.

And even after that, the events that occurred were an indictment of the system too. A lot of these prisons are set up in these rural areas that are mainly white—and the hospitals in the surrounding area wouldn't take Black people. So the people had to be taken several miles away to a major city to get into the hospital because they just wouldn't take them in the local hospital because they were Black. And people were saying, "This is something they will have to pay for." This was just another crime of imperialism and another reason why they had to be overthrown. But it wasn't like we felt scared or intimidated, even though they had done this dastardly deed, this cowardly deed. We were angry.

RW: People saw it as a battle in a bigger war?

Comrade X: Right, and I can recall the spirit in solitary. They put us in solitary. We had to carry the injured from the recreation yard out into the prison compound. And we laid them on the grass in front of the prison hospital. And the rest of us were taken into solitary and put in 10 or 12 or 15 deep. And these cells are no bigger than 8 x 10 or 10 x 12. So we were crammed in there, but the chants and the slogans and the singing and the spirit was absolutely electric.

RW: The Chairman has said, if you want to be bad, the revolution is the baddest. Reflecting back, you had been faced with death before in your life, how would you compare the difference?

Comrade X: In some of the Chairman's writings he talks about the difference between soldierly courage and revolutionary courage. I have yet to see that in its most profound sense, you know, in terms of taking a leap into revolutionary warfare. But in a more miniature sense, this was an example of seeing that. On the one hand, if you're going up against someone else who is oppressed like you, whether it's for "face" or all those other kinds of things of the street code that I was talking about earlier [See Part 1, "Fried, Dyed and Laid to the Side."], that's one thing that's a certain kind of courage. Or even if you are going up against the state—like I would go into these places and be ripping off something and then cook my breakfast—that was one thing. But it's another thing when you are going up against the enemy, the awesome power of the state. That's a whole different ball game in terms of having the courage to do that.

The whole point about dying that Mao made in the Red Book is this: to die for the people is heavier than a mountain, but to die for the imperialists is lighter than a feather. And there was a whole spirit in that period that captured all of us, about the willingness to put your life on the line for the people and die fighting imperialism. And we not only felt it then, but we have not given up on it. And I think that's a lot of what the youth have to get down on. The courage they have in one context has to be translated in terms of going up against this whole system and bringing down this whole thing. Because one of the things we understood then in a basic sense is that without power, everything was an illusion—that once we could bring these people down then we could perform miracles.

RW: You mean state power, taking on the whole system, not just having a piece of turf?

Comrade X: State power, taking on the whole thing, not just having a block or having a corner or having part of a city, but taking on the imperialists and overthrowing them in revolutionary warfare and establishing socialism and beginning to move on towards communism. That's the whole vision that I began to develop back then. And that was a whole different kind of thing.

Part 3: Changing the Terms

RW: Do you remember the first time that you realized that it was going to take a revolution against the whole system to deal with the problems coming down on Black people and all the other social problems?

Comrade X: When Fred Hampton was killed—this was part of the events that set me on a certain trajectory. It was some months after we had been shot in the prison rebellion I told you about earlier. [See Part 2, "Burning Down the House."] And it was obvious to me, knowing the nature of these people, having lived in the belly of the beast, even within the belly of the belly, it was obvious to me that Fred Hampton was assassinated. Some things came together. There were some things that were there in my thinking and my understanding, but some things came together on a much higher level around that time.

Leading up to the prison massacre in 1969, on one level I looked at myself as a revolutionary. Those events combined with the Fred Hampton murder, those were crucial things that played a certain role in terms of me crossing a line in the sense of feeling that this is what I wanted to do with my life. That was the most profound turning point, if you want to put it that way. There was no turning back.

RW: If someone had told you a few years before that you were going to be a revolutionary leader, what would you have thought?

Comrade X: I wouldn't have believed it. But the fact that there was the Black liberation struggle and a revolutionary movement that existed at that time played a tremendous role in propelling a lot of us forward into becoming what we were. In the years earlier when I was just a street youth doing my thing, I would have never thought of it. But here you were, you were thrust into a whole period where there's a lot of upheaval throughout the world and in this country and even reflected in a microcosm kind of way in prison. And you were propelled forward to take a stand.

When I first went into prison I was just going to do my time and get out and I didn't see any reason to get involved in anything that would interfere with that. In fact, when I was first let out of quarantine, there was a race riot that went down in the cell house that I was in and it was very violent, with bottles and shit being thrown off the range and people being hit with steel pipes. And I had some knowledge of the oppression of Black people and the contradictions that existed on that front, but I didn't see myself taking either side. It was just something I was thrust into.

I didn't understand what people were doing and I didn't see a reason for it. But it really hit me that people not only believed in what they believed in, but they were willing to put their lives on the line for it. That made me sit up and take note—to try to dig into it more to find out why it was they were doing that. I had no sense at that time that it would even be possible to bring the imperialists down. On the level of individual rebellion or going up against the police in an individual way or with a few friends or whatever, I had done that, but in terms of being able to mobilize a mass of people and to field any kind of army to bring them down, I had no sense of that, I had no sense of the possibility of that.

Mao says that the oppressed are oppressed and in fighting back they search out a philosophy. And that's what I did. I couldn't read that well, I hadn't really been that interested in school when I was growing up, especially a lot of the history they taught at that time. When you read the school history, it was the slaves picking cotton and that sort of thing which was just humiliating—you were just glad when the class proceeded past those pages. But when I got in prison—and got affected and influenced by all of what was going on in society and throughout the world—I began to take some steps to try to understand things better.

First it began by FIGHTING against the prison authorities, and through that I began to dig more deeper into what this shit was all about. I went into the situation of Black people in this country, how did that come about. One book I remember was called Black Cargoes about how people were packed into these slave ships and the conditions were so horrendous that a lot of times the slaves would just jump over and kill themselves rather than to put up with it. All those things began to come together for me in terms of understanding more about the oppression of Black people in this country and how and why it had to be ended and it only could be ended with violence. It couldn't be ended through praying or marching, it could only be ended through an armed struggle. That's what I came to understand through my experiences.

RW: So it was like Mao talks about learning warfare through warfare.

Comrade X: Very much so, very much so. It was just being thrust into the struggle with the other side and a lot of that raising questions about what kind of society you would replace it with. And I can remember being just excited and thinking about not only how they can be defeated and how they can be brought down but getting a beginning vision—from what I could understand of things like the Cultural Revolution in China under Mao's leadership—of what the society would be like having done that, having overthrown the system, what kind of society would it be—that we can deal with a lot of these problems in terms of the oppression that the masses of people face, the humiliation and degradation, the rich over the poor, men over women, whites over Blacks and other oppressed nationalities and so forth. And that overthrowing them would be a big step in wiping this shit out not only in this country but throughout the entire world. And that vision was very inspiring to me when I began to take up and study Marxism in a serious way—and it has been deepened and enriched over the years since that time.

RW: That's the strategic Double C—contempt for the enemy and confidence in the masses that the Chairman talks about.

Comrade X: Right, it's based on something, it's based on the party which is armed with the most revolutionary science that exists today. And I learned this through the crucible of struggle against the enemy. I explored a lot of different philosophies but I came to see that this was the most advanced philosophy that exists. This was controversial. Some people said back then, "Well, that's just for the white boy" or "That's the white man's philosophy"—just like some people say it today. And in fact one of my best friends stopped talking to me because he disagreed with my insistence that we had to unite all who could be united against the enemy, including white people. That was very hard because we had been through some heavy struggle together. Later he came around. But for some months he wouldn't talk to me. But I stuck with it because this science is the revolutionary philosophy, the most advanced philosophy for people all over the world because it is a LIBERATING PHILOSOPHY.

RW: At a certain point after the rebellion in '69, the prison authorities moved you to another prison.

Comrade X: Yes. I was moved to a different prison. There was not the same level of revolutionary consciousness as there had been before cuz the place where I was moved had much older prisoners. And it was much more of a stifling atmosphere where you were locked up longer periods of time. And this was a very difficult period. To tell you the truth, on a certain level, in terms of my spirit, I almost died for the first year or so.

Then a lot of younger prisoners began to be sent in from other places and some of the character of the prison began to change and two or three years later the level of struggle changed even there, but for a couple years or so it was a very difficult transition to make.

RW: How did you deal with that? Was this a tactic of the enemy to cool things out?

Comrade X: The tactic was precisely to try to separate the leaders off from the broader prison population, and in large part the way that was dealt with was to try to draw strength and inspiration from what was going on in society as a whole, and there was a tremendous amount going on at the time.

George Jackson

One of the things that had a big impact on me was George Jackson and his writings, and that was all part of trying to get a better understanding of and being positively affected by the Black Panther Party. One of the things that really hit me a lot about George was this thing of becoming a revolutionary under very difficult conditions and overcoming some obstacles and barriers to actually become a revolutionary leader. His heart was fundamentally with the people, and the determination he had in the face of threats and intimidation to not give in and not capitulate on his revolutionary principles—that was something that had a very powerful impact not just on prisoners but on a lot of other people.

The Attica rebellion was something else that had a very powerful impact on me in terms of the courage and the determination and the fearlessness in the face of the enemy. But also too the revolutionary consciousness that was reflected in that rebellion. One of the demands they were putting forward was that they be allowed to go to a non-imperialist country. So that had a profound impact on me and thousands and thousands of others both inside and outside of prison.

So I was beginning to take up the science of revolution—Marxism-Leninism-Maoism—in a more thoroughgoing way. And then at the same time at one point, under the cover of doing Black history class, the small core of revolutionaries began to reach out to broader prisoners. There was some discussion of Black history but at the same time there were efforts through that to raise the consciousness of the prisoners and also to link up with some people who were more interested in revolutionary politics. So that's how we survived and sustained that period and then later there were significant outbreaks that went on in that prison that we were right in the middle of.

RW: What were some of the obstacles that you had to get over to carry out this revolutionary work in the prison? You are under the gun and you have to deal with that, but also there is a strong cult of survival in prison. Sometimes people say that in prison "you must bite or be bitten, or you must eat others or be eaten up by others." How did the revolutionaries deal with this?

Comrade X: I think again, first and foremost, we have to look at the climate that existed throughout the country and throughout the whole world. And including at that time, a sense of unity that existed even on a basic level between Black people—for instance, that's when the terms "brother" and "sister" and all of that began to be brought to the fore. But I must admit that even with that political atmosphere in the world, in prison there was a question of GOING AGAINST THE TIDE. You were going against the tide in terms of everything you were doing. But I think in the context of a whole revolutionary movement in the world and in this country, there was the ability to stand apart from some of the dog-eat-dog, "bite or be bitten" atmosphere that was promoted in prison. And there was often a lot of struggles with people.

There's a whole thing that goes down in there. The younger guys who come in are preyed on by the older guys, and there was a whole thing as we were trying to organize and do what we were doing in the prison that we didn't tolerate that, that people came in and especially as they were taking up revolutionary politics and what not, that we would oppose that mentality and wouldn't tolerate that in terms of the younger guys coming in and being raped and those kinds of "bite or be bitten" kind of outlooks.

RW: You know I have noticed that among some men revolutionaries who have been in prison there seems to be more of an understanding about not treating women like sex objects and property. And I was wondering if this was because men in prison actually go through some of the same abuses that women do—where power relations actually take the form of sexual abuse—and the whole question of being treated like a sex object is so intense. Speaking of going against the tide, this must have been a big topic of struggle.

Comrade X: That's an interesting thought. I think for myself and for a lot of others it was more a question of being forced to confront that if you were going to be down for revolution, then you couldn't at the same time be for oppressing women. There was an analogy that you didn't want to be called 'boy" and you didn't want to be called "nigger" and all of that, and if you didn't want to be subjected...

RW: If you didn't want to be raped...

Comrade X: Yeah, that whole kind of thing, then how could you do that to women. I don't know that the example you're making was consciously filtered through, but I think it was more a combination of things, including the fact that a lot of women were in the streets at that time around women's liberation, to say nothing of the women who were engaging in armed struggle in Vietnam and elsewhere in the world. And that had a certain impact. But like the Chairman talks about in his book, A Horrible End, or an End to the Horror? you have to "prove it all night." I do think on the woman question you do have to "prove it all night." It's not some question where you just "get it right" and don't have to struggle over it anymore, speaking especially of the brothers.

But I would say for myself it was something that I had to come to grips with and really break with some things. Like in growing up and before I became a revolutionary, you could be against being called a "nigger" or "boy" or being called "colored"—and this was a lot of the things that people would throw down around in those days. But prior to becoming a revolutionary, all the kinds of degrading ways that men treat women, it wasn't something I had even thought about. Things have a certain edge now, but when I was coming up it was a real problem too—a problem among the oppressed themselves. Even in some of the common language that the kids would use about "pulling a train" on women—it was just rape, you know. A woman would be interested in one person and have sex with one person and several other guys would be waiting to get in on it too. And when you stop and think about it, it's really anti-women. It wasn't about sex—it's about "this is a power trip." But that was looked at positively among the men. Or you would go out with a woman and she would get a few drinks and she'd get a little high or something and then you would force yourself on her. That was rape but it wasn't looked at that way. It was looked at by men in a positive light. And there were a thousand other ways this shit came down—and still does. So it's very good that there is a lot of controversy coming out these days and this type of behavior is being exposed for what it is.

When I was a kid some of the people we admired were the pimps. In fact, there is a series of books that were written—I was in the bookstore the other day and I see that they are still out there—a series of books that were written by this guy called Iceberg Slim who was a pimp. And the young brothers would read those books and admired his style and where he was coming from. And thinking back on it now you can see how far some of the brothers had to come. I'm speaking now of the period of time before I became a revolutionary and started taking up revolutionary politics. On the streets it was considered hip to be a pimp, or a "player," which was a term for a guy who lived off the money a woman made on the street. To have a Cadillac and to have several women, that was a goal to aspire to. And those very brothers who looked toward the pimps and admired them and in some cases did actually do that themselves, if they had been forced into some form of servitude in that kind of way, they would have been totally outraged about it. But in this case, it was something that was part of being cool, and it was considered part of being cool to dog women in this way and to actually end up being a slave master in this type of way. And that's the screwy relations and contradictions that you actually get under imperialism.

Men can't say that we're against imperialism but at the same time carry out the imperialist mentality in relationship to women. There's no way that you can carry through a thoroughgoing revolution in that kind of way.

RW: Right. But at the same time it is hopeful to the people and to the sisters in particular that through fighting the power and taking up the science of revolution people can change.

Comrade X: And there is a much more powerful basis to do that today. The Party has put this question out pretty sharply including this slogan: Brothers Don't Be Dominators, Rise Up With Sisters, Strong Proud and with Equality, Fight the Power, Bury the System. And I think that whole orientation that is being fought for is a very good basis to make a leap even farther than we went in the '60s, because in the '60s this question was not well understood.

RW: So you see that this is going to be an even hotter question in the 1990s?

Comrade X: This is already a hot question and I think it will be resolved in a much more profound way than in the '60s. There's a war now on women—from the highest offices in the country. And I think that there is the question of taking a stand: are you going to be PART OF THE PROBLEM OR PART OF THE SOLUTION? And I'm not saying that to be pessimistic about it. I think there is a profound basis to resolve this on a much higher level and a much more thoroughgoing way than it has been previously. This is definitely a big aspect of carrying out a thoroughgoing revolution.

RW: So you think it's posed pretty sharply to the young brothers—are they going to hold onto their macho attitudes or unite with the women who are rising up against the powers.

Comrade X: Right, I think this is putting it sharply to 'em, but I think from everything I'm hearing and everything I'm seeing these days, there's a lot of sisters that are determined to make 'em get the point.

RW: Getting back to your revolutionary work in prison, you were talking about how the revolutionary core would begin to change the terms in struggling with people over these things.

Comrade X: Right. In some sense it was kind of like the seeds of dual power—even though they had us locked up. Once we began doing what we were doing and setting a tone in a different kind of way—it's not that we were setting ourselves apart from the rest of the prisoners—but it was that we were conscious and we were revolutionaries and we were trying to recruit other people to be that. And once people began to ally themselves with us, other people wouldn't bother them, in terms of trying to rape them and that sort of thing. So we did try to set a certain tone—not that we were missionaries or some kind of Christians or something—but we tried to set a certain tone in terms of where we were coming from in being revolutionaries and setting a certain standard.

This actually meant putting your life on the line too, sometimes. I can remember an incident where there was this gang in prison that was extorting people and ripping people off and what not, and a lot of the prisoners who weren't so political, they came to us saying look, this shit is going down and we are going to deal with it and what are you all going to do? And we actually went and confronted the gang leaders and said, "Hey, look, this is divisive, and this is a question of getting people all divided up," and actually we were able to change some of those goings-on without resorting to any kind of violence. Through struggling with them we were able to change things in terms of some of the kind of stuff they were doing inside the prison.

RW: Was that by relying on a certain atmosphere and initiative that you had?

Comrade X: Right, and even some of the gangs were forced to have respect for you because it was the kind of thing of "Those brothers there, they are not into a lot of foolishness, but when it comes to going up against the prison authorities, they are for real." There was an expression in prison—"they are for real."

When we first began to be revolutionaries, people would respond to you by saying, "Well, you wasn't doing that shit before you came in here." That was their response to you. But more as they saw you going up against the other side, being fearless and being uncompromising and determined in going up against the other side and not selling out, even some of the more lumpen elements, they were forced to have begrudging respect for you on a certain level.

So you had to learn all kinds of tactics for dealing with different contradictions, including, like you mentioned earlier, that you were working directly under the gun. And we were always having to apply Mao's teachings on who are our friends and who are our enemies and knowing the enemy well.

For example, there was a work stoppage that I played a role in organizing. And we were actually trying to sum up what had been previous experience in going up against the prison authorities and what their tactics were. One of their tactics was to immediately try to grab the leaders and the whole thing would die. So what we did was we organized different layers of people, so as they grabbed these people, some more would be waiting in the background and they would step forward. But despite all that planning, we had made a mistake and somehow I ended up with some leaflets in my cell.

And I will never forget it, these three guards came to my cell. And they were calling me "sir" and "mister" and all of this. And right away I could read that they were afraid of getting into a confrontation with me and having a fight with me because they figured that they would really set off some stuff they didn't want to happen among the other prisoners. So they were very delicate with me and they were calling me "mister" and "sir." So right away I thought of what to do with these leaflets.

I had the leaflets in an envelope. So I started putting on an act and I said, "Oh shit, man, why do you want me." And they said, "Well, the warden told us to come and get you and lock you up." And I said, "What for? I haven't done anything," playing along with them. Then, finally I said, "Well, damn, I've been working on my legal case and I have these papers I have to file. Would it be possible for you to take these three cells down the range and give them to so and so." "Oh, sure, Mister so and so," they said. And they took those leaflets and gave them to someone else and that was the hard evidence they would have had that I was deeply involved in this whole work stoppage.

So that was a funny story—and it goes back to this question of strategic contempt and knowing about their strengths and weaknesses and taking advantage of those. They were relieved that they didn't have to attack me and lead to some kind of rebellion—because I was like a leading figure in the prison and if they had attacked me and beat me up that would have led to some serious consequences they weren't willing to confront. So I was able to read that situation and take tactical advantage of it.

Part 4: In the Spirit of Attica

Attica Rebellion, 1971. AP photo

RW: How did the revolutionaries unite the brothers in the prison to take on the powers?

Comrade X: A lot of times when we were involved in mass struggle it was a situation where things had gotten to a point where they were going to break and a good majority of people would be in unity with what was going down. And sometimes things which turned out to be very important kicked off in a brainless way. In fact, I can recall another incident that I was involved in where the initiators were some of these gangsters who had come up against the prison system and they were on a protest. And one of the things that they were going to do was something similar to what we had done earlier which was to have a protest in the prison yard within the range of the gun towers and everything. So we went out amongst them and struggle with them and said, hey, this is not the correct tactic, this has been tried before and this is part of our experience and this is not the way to go.

RW: What was the issue they were protesting over?

Comrade X: This was some years after that previous rebellion and by this time I considered myself a communist. There was a series of things that had mounted up in terms of the general living conditions—which always mount up after a period of time—but there were things going down like people dying under mysterious circumstances. For instance, there was this young kid. He was not that much younger than I was at the time, but he was one of these street kids who was bad and he came in and got into some contradiction with another prisoner and got in a fight and later the other prisoner came back and threw some flammable fluids on him and burned him up. And after they had treated him medically, they put him in solitary confinement for over a year and a half, and he gradually began to deteriorate and eventually one morning he was found hanged in his cell. There was a lot of speculation as to whether or not he had been murdered, because, if I remember the facts correctly, his hands had been tied behind his back. But whether he was directly hung by the guards or whether he did it himself, ultimately we saw it as murder.

RW: How did the revolutionaries respond?

Comrade X: At the time I was in segregation, I had been put into segregation for four months for refusing to button up my coat—it was one of those kinds of things.

We had somehow gotten hold of a press or a mimeograph machine. I don't recall all the details of how we acquired it. I think we bought it with cigarettes, which is like the prison currency. But somehow we bought it from one of the prisoners who worked in one of the departments. We had all been reading What Is To Be Done? by Lenin, and we were really fascinated with a lot of what Lenin was talking about in there and really picking up on the whole idea about trying to work under difficult circumstances, and the question of trying to work secretly was what we were zeroing in on. And that gave rise to a lot of brainstorming and thinking on how we could apply some of Lenin's thinking in there.

In prison it was difficult circumstances in terms of applying revolutionary theory, but we did to the extent that we could try to combine theory with practice, and this is one example of it. We acquired this press. So sometime after this guy was murdered, we printed up a leaflet basically indicting the prison authorities for his murder one way or another and we managed to distribute it secretly throughout the whole prison. And the prison authorities blew a head gasket that this level of organization actually existed in there. And before we had did it, we had a lot of discussion back and forth about how to conceal the press and there was a lot of discussion about dismantling it and hiding it on top of the cell block. And the upshot was that they locked the whole prison down. They went around and tested every typewriter to see if it corresponded to the leaflet. They tested as many typewriters as they could—because they couldn't find the one that we used—to see if they corresponded with the leaflet. And they also tore the prison apart trying to find the press. Maybe we even buried it, but the upshot was that they didn't find it. And this was electrifying and inspiring to the other prisoners that this actually could go down and they were not able to find out how it happened. So in terms of developing tactics and trying to apply theory, that was a good example.

So there was a whole series of things like that. And then I think there was an immediate precipitating factor like a fight between some gang members and they got locked up and they were trying to get their comrades released from solitary or something like that. And this is what immediately precipitated the idea of a protest among these gang members. So those of us who were more conscious revolutionaries went out amongst them and struggled against just taking this tactic of having a protest in the yard right in view of the guard tower because we had seen that before. So after we struggled with them, they were dissuaded from that and they apparently went back to their cell house and took it over.

We revolutionaries were mainly housed at another cell house, so as we were walking toward the cell house, we saw this prisoner with the keys. And we weren't real happy to see this particular guy with the keys—he was a loose cannon, so to speak. He was hollering at us, "Well you better hurry and come in," so we didn't have any choice. What were we going to do? We certainly wouldn't have taken a position of, "Hey boss, we're not involved in this"—they were going to deal with us regardless. We had crossed that line and we had put ourselves in a certain position in relationship to the prison authorities, and there's no way we were just going to say, "We organized the last one but we didn't organize this one." So we went into the cell house and what we tried to do was to get involved and give the takeover a certain direction. And we ended up taking over the prison and we had several guards hostage, instead of repeating the events of 1969.

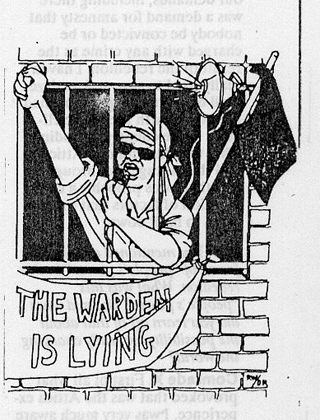

We also heard over the radio where the warden was telling lies that this rebellion had happened because of the weather and other such ridiculous shit, and basically we just wrote on a sheet, "The warden is lying," and hung it outside the windows where people could see it from the street. Then later we set up a public address system of our own.

Some of the prisoners had record players and speakers and somehow somebody was able to rig up a sound system. The cell block that we were in faced out toward the street. So we were able to rig up a system where we could be heard over the walls out to the street where there were people who had gathered to support us, families and all that. And we were able to agitate about what we were trying to do and what we were trying to accomplish. So there was a level of organization and certain forms of "people's power" that actually went on in that particular cell house that didn't exist in the other places. And we were prepared to die for what we were doing.

This was a situation where again it was not clear that we would live through that. We did have a division of labor where a few of us were outside, not actually involved in it, who were going to play a role in terms of trying to help sum some things up after, if we had gotten killed. And we said our goodbyes. This was in the wake of Attica and the wake of the murder of George Jackson, and it was not altogether clear that we would not be murdered too.

What happened was that, after 36 hours, they backed down and basically conceded to our demands, including there was a demand for amnesty that nobody be convicted or be charged with any crime as the result of the rebellion. I haven't really tried to stop and analyze it all, but I think it probably had a lot to do with the whole climate in the country, including what they had done in Attica and the outrage that brought, and there was probably a combination of factors that forced them to back down.

RW: You mentioned certain forms of "people's power" in this rebellion. What was this "people's power" like and what did you learn off of that about the possibility for really changing the world?