Carl Dix: The New Jim Crow at the Baltimore Sparrows Point Steel Mill

May 11, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

In the wake of the police murder of Freddie Gray and the resistance and rebellion among the Black youth of Baltimore, there has been a lot of discussion about not just the problem of police murder and brutality, but also deeper problems like poverty and unemployment. Like many other cities around the country, tens of thousands of jobs have “disappeared” in Baltimore due to de-industrialization. The steel mills and other manufacturing plants that once employed thousands in Baltimore have left and set up production in other countries where wages are lower and working conditions are worse, where bigger profits can be made. From the 1950s to 2000, the city lost more than 100,000 manufacturing jobs. The industrial workforce was depleted by 75 percent. Today in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood where Freddie Gray lived and died, the rate of unemployment is around 50 percent, about double that of what it is in the city as a whole.

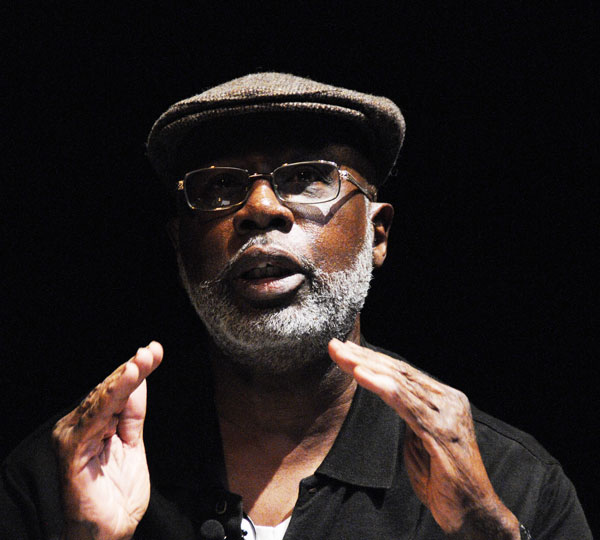

The following is from a Revolution interview with Carl Dix. He talks about his experience working in the Baltimore Sparrows Point Steel Mill in the 1970s and about how, when Black people did have factory jobs in Baltimore, they faced systematic Jim Crow-type conditions of segregation and discrimination, given the worst, dirtiest, lowest paying, and most dangerous jobs.

Carl Dix is a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party, and is the co-founder, with Dr. Cornel West, of the Stop Mass Incarceration Network.

I was born and raised in Baltimore. I lived there the first 35 years of my life. As part of that, I worked for five years at the Sparrows Point steel plant in Maryland, from 1973 to 1978. Sparrows Point was one of the main industrial plants in the Baltimore area. There were others. There was another steel mill, a couple of shipyards, auto and electrical plants. But Sparrow was a place that a lot of people wanted to get work because it paid a bit more than some of the other places. At that time, at its height, the plant would employ about 20,000 people. But I found out after getting hired that there was a real boom and bust to how that went because when they had things going they had 20,000 people. But then the bust would come and they would employ only like one or two thousand, and everyone else would get laid off. There was a feast and famine part to it that you found out later.

But just getting hired and going into the plant for the first time, I was really struck by a couple of things. I got hired on the finishing side or what was called the tin side. The other side was called the steel side. The other side was where they took the raw iron ore, melted it down and formed it into the steel, which I guess is an alloy of iron. I was on the side where they would take the steel and finish it into sheets, different things like that, for different uses. So I was on the side where the pay was a little better and the work was viewed as a bit easier. And one thing that was striking when I first went into the plant, the first thing I saw was that for every restroom, there were two together. And not male and female. There would be two men’s bathrooms together, two women’s bathrooms together. And you kind of wondered like, why was there two next to each other like this. And it turned out that the reason was that up until a bit before I was hired there had been “white” and “colored” bathrooms in the plant. They had taken the signs down but the bathrooms were still there.

Sparrows Point steel plant, 1973.

Then the other thing is that I got hired into this department on the finishing side, and I noticed that the department that I got hired into—and most of the 20,000 people who worked there were Black. On the finishing side it was a little more than half Black, if you went over on the steel side, where the coke ovens, blast furnace were, where the harder and dirtier jobs were, then the percentage of Black workers went up quite a bit; lower paying, harder, more dangerous. But then even within this finishing side where the pay was higher and the jobs were easier, stark discrimination hits you just walking into the plant because there was an all-Black labor crew, mostly made up of older Black guys. They were a sub-department of a larger department and they were all Black. And they were the ones who taught us to do the jobs when they hired a lot of new people in. And we would start off as laborers, but then we could work the machines. And these guys in the all-Black labor gang knew how to work all the machines, and they were the ones who would train us how to work the machines. And if there was a shortage of people at any position on the machines, the guys from this labor gang would step in and run the machines where you would make a lot more money, ’cause first off, your base pay was higher, but you could also get bonuses based on production, which laborers couldn’t get. And we also found out that this was also a Jim Crow relic because this was from back in the days when all of the Blacks went into the labor gangs and only the whites got to work on the machines. And even in those days, they would train the white guys to work the machines and the Black workers were not allowed to move into these positions. They could work them as a stopgap thing if they needed them, but they could never move in and be promoted to that position. And these were all older guys, who at this point no longer wanted to move in and promote up. But you had a stark reminder of the Jim Crow period that had just recently ended in the plant by this all-Black labor gang.

And I talked about how these were easier, less dangerous jobs. But that doesn’t mean there was no danger on this side of the plant, because very early on, I remember one of the new guys who got hired was working on the midnight shift and this machine was flattening the steel into thin stripes. And it broke off and went flying into the area where the workers were and cut the guy’s finger off. And like this was the guy’s first week on the job and he loses his finger. This was kind of chilling, and you’re kind of like, oh, shit, this is what I’m getting into.

And then later during a big layoff, I found that I could transfer into the steel side. When I say the big layoff, I’m referring how the number of people working in the plant dropped from about 20,000 to about 5,000 in 1975, when I had been working there for about two years. Things had always been cyclical in the steel mill. There would be times when they had a big backlog of orders and people would be working, then there would be times when there was a big drop that would last months, even up to a year. And it wasn’t something they explained to us, they just laid people off. This was a time when steel factories were moving out of U.S. cities into other areas and more steel production was being done overseas. But that wasn’t the full reason for the layoffs because they did go back up after about a year. One thing that I did find out was that if I wanted to continue working and not be on unemployment and then run the risk of that running out and then having nothing, I had enough time to transfer over to the steel side, because it took a lot less seniority to be able to work in the coke ovens than in the finishing mills. So I did transfer over there and do that. And most of the people I was working with were considerably older than me, although you could miss how old they actually were because a lot of them looked real old and had serious physical ailments. But that actually wasn’t a function of their age. It was more a function of the jobs that they were doing, because the jobs were much more physical and the possibility of getting injured was much, much greater. One thing that happened to a lot of people is that people suffered a lot of burns working in the coke ovens. Because even if everything is going right, the pressure within the ovens could shoot one of the lids off and it could hit you. And the lids were like very, very heavy. But you weren’t mainly worried about the physical damage of the heavy metal hitting you, but it was like also extremely hot. And if it touched you, it would burn through several layers of your flesh. And rare was the coke oven worker who had not had this happen to him at least once.

What happened to me wasn’t that I didn’t just not dodge the lid fast enough. That did happen to me once and I have a scar from that. But I had a much bigger problem. This actually happened during a coal miner strike. There had been a slowdown in production because the coal miners were on strike and we weren’t getting as much coal. And what they would do is they would do what they called “stoke the ovens.” Because normally, you would be producing coke to melt the steel on a daily basis, but then with the slowdown of coal you were no longer able to do that. So instead of running and clearing the ovens on a daily basis, they would clear them out on a weekly or even on a monthly basis, depending on how long the coal strike went. This was a particularly prolonged one, as I recall, so the ovens hadn’t been “pushed”—that’s what they called it—in a month. So then when the coal strike ended and they started pushing the ovens, they were having a big problem with getting the coke to go down the conveyor belt, which they said they always did when there was production slowdown like this caused by disruption in the supply.

So they sent a couple of us down to clear the conveyor belt. We go down there and what we find out is they usually run water on the coal so it is no longer inflamed when it is on the conveyor belt. But we got there and we saw that the coke was still inflamed on the conveyor belt—we figured that had something to do with why it wasn’t going through. But then as we started trying to clear it, after about half an hour, it just started to explode, sending flaming particles flying our way. And we were in an enclosed area with a wall behind us, so we were kind of trapped there with these flaming particles flying down on us. The other guy was standing near the door to the enclosed area, so he was able to step out the door and get behind the wall. I was between two doors and I turned to run to the door and as I ran, I was showered with these flaming particles. They were on the ground in front of me and I’m stumbling over them and I fall and I get severely burned on one side of my body—the side that was facing the particles. I ended up with deep second and third degree burns over 25 percent of my body.

And it was interesting, though, because I was in shock when this happened. So I can smell burning hair, which is a very normal smell in the coke ovens, because people’s hair gets singed all the time, but I couldn’t actually tell I was severely burned and it didn’t hurt. So I get out there and the guy asks me am I OK, and I say, yeah I’m OK. He looks at me and he could tell I wasn’t, but he doesn’t want to break the news to me. The foreman calls over the line and says, what’s wrong over there? And the other guy says, we got a problem. And the foreman asks, can you get the line going? And the guy says to him, we got a problem over here. And the foreman says, I don’t care about your problem, can you get the line going? This angered me, and I’m like we could have been killed over here and he wants to know can we get the line going? I said, I’m going to go kick his ass. And because I was in shock, I was not aware that I was not capable of kicking his ass at that point. And the shock did not wear off until I got just outside his office, at which point I could no longer stand up because of the severity of the burns. I ended up spending two months in the hospital and I had to get several skin grafts.

In that particular instance, I was the only one hurt. But what I found out later was that whenever they went off the schedule of pushing the ovens everyday, they had that problem of the conveyor belt, and they sent people down and people reported being sprayed by flaming particles. But it was never spread among people. So when I went down there, it had already happened to other people, but I was the only one with severe burns. Other people had gotten minor burns for it, but no one had ever been caught between the doors like I had and had to run out. But it was a problem that had happened before, but no steps had been taken before to minimize the danger to the workers being sent down there.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.