Upheaval Against Femicides and Women’s Oppression Shakes Up Mexico

| revcom.us

In Mexico, there is a rising epidemic of femicides—murder of women because they are women. This is a concentrated expression of the extreme and intensifying patriarchy and oppression of the half of humanity born female. There were 1,100 femicides nationwide in Mexico last year, and femicides have increased 137 percent in the past five years.1 In the face of this, a growing upsurge of people determined to struggle for an end to femicide, rape, and other brutality against women is deeply shaking Mexican society. This has taken leaps in recent weeks, with fierce protests and a call for a March 9 “Un Día Sin Nosotras” (A Day Without Us Women)—a national strike to demand an end to violence against women.

The call for the March 9 action was issued by Brujas del Mar (Witches of the Sea), a women’s collective from the state of Veracruz. The collective said that this is a movement for all women and men, and that people need to come together for the common good.

This movement has been gaining broad support throughout society, including well-known public figures like actresses Mariana Garza, Giovanna Zacarías, Andrea Méndez, and Ximena Martínez and journalists Denise Maerker, Carmen Aristegui, and Martha Debayle. Officially, 12 universities have joined—including the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the National Polytechnic Institute—offering spaces and support for the day’s activities.

Various unions, mass organizations, as well as even some government agencies are taking up the call or offering support for the day. The mayor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum, said that city employees would not be punished for taking the day off to go to the protests. Meanwhile, Olga Sánchez Cordero, the federal secretary of the interior, admitted that the Mexican government is late in taking measures to deal with violence against women—at the same time, President López Obrador (who masquerades as a socialist-minded progressive) has been warning people to be careful about participating in the March 9 events, claiming that those behind the movement are like the reactionary pro-U.S. forces behind the 1973 coup in Chile against Salvador Allende.2

“We won’t be silenced”

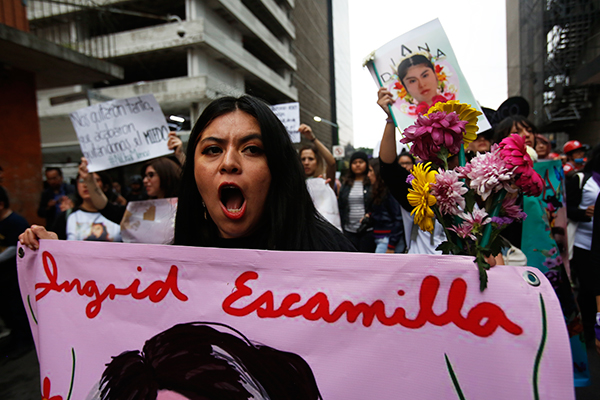

The opening month of 2020 saw 73 femicides in Mexico—compared to 33 for the same month five years ago. Then on February 9, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was murdered in a gruesome manner in Mexico City, allegedly by her male partner. Newspapers published leaked photos of her mutilated body on the front pages, provoking outrage in the streets.

This was followed by the kidnapping of 7-year-old Fátima Adrighett by a family acquaintance as she was leaving school in Xochimilco, south of Mexico City. Her body was found days later, and it became clear that she was raped, beaten, and murdered after she was kidnapped. The alleged kidnapper and her male partner—a wife batterer—were arrested after they reportedly told a family member that they had taken Fátima because he wanted to have her for his own use.

On February 14, 17-year-old Josseline was murdered, allegedly by her uncle, in a motel in Coacalo, on the outskirts of Mexico City.3 Her body was found the next day. People marched and protested in anger on February 21.

Protests against femicide and other anti-women violence have been increasing in number and participation in recent years. On November 25 last year, 6,500 people marched in Mexico City for the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women—joining hundreds of thousands of women, along with men, who took to the streets in many countries across the globe.4

On February 9, in response to media’s publishing the images of Ingrid Escamilla’s mutilated body, protestors gathered outside the National Palace (seat of the Executive Branch in Mexico). Fake blood and slogans such as “We won’t be silenced” and “Femicide State” appeared on the façade and doorway of the building. The protesters, most of them women, read a statement saying, “It enrages us how Ingrid was murdered, and how the media put her body on display.” And, “It enrages us that people judge us, saying ‘this isn’t the proper way to express your rage’...We are not mad, we are furious.” They then marched through the streets chanting “Not One More Woman Murdered.”

On Twitter, people have been using the hashtag #IngridEscamilla to spread words of solidarity along with photos of landscapes, flowers, and mountains. This has become a way of burying the gruesome photo of her body circulating online so that she does not continue to be victimized in death.

A Just Struggle

The vast majority of the cases of femicide in Mexico are never solved—a small percentage are brought to trial, and a tiny percentage of perpetrators are convicted. Along with femicide, the numbers of rape, sexual harassment, domestic violence, and other brutality against women are all on the rise. All this is part of an intensifying climate of misogyny (hatred against women).

The growing mass outcry and protest against femicide and other violence against women in Mexico is completely just and must be supported.

1. Diario M. Noticias, “No quiero que los feminicidios opaquen la rifa;” AMLO, February 10, 2020. [back]

2. “López Obrador defiende derecho a la protesta y pide no dejarse manipular”, La Jornada, February 22, 2020. [back]

3. “Realizan marcha por feminicidio de Josseline en el Edomex,” La Jornada, February 22, 2020. [back]

4. “Miles de mujeres hartas de la opresión patriarcal se manifestaron en las calles en #25N MX,” Aurora Roja, Revolutionary Communist Organization, Mexico. [back]

Demonstrators during a protest against gender violence in Mexico City, Friday, Feb. 14, 2020. The protest comes after last week's vicious murder of Ingrid Escamilla by her boyfriend and controversy unleashed by the leaking of images of her body to the press, in a country where an average of 10 women are killed every day. (Photo: AP)

Mexico City: Demonstrators against gender violence covered the National Palace in fake blood with the message: "Femicide State," in Spanish, February 14. (Photo: AP)

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: