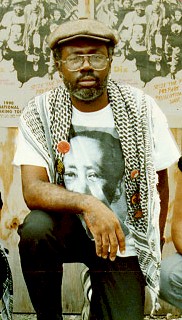

Carl Dix

Revolutionary Worker #1188, February 23, 2003, posted at http://rwor.org

In early January a very powerful and moving "Call to Conscience to Active Duty Troops and Reservists" was issued by a group of veterans of the U.S. armed forces. These vets came from many different political perspectives and from different wars--from World War 2 on up to the 1991 Gulf War. More than 550 vets have signed the Call so far and they include well-known people like Howard Zinn and Michael Moore. One thing unites them all: staunch opposition to the U.S. plans to launch war on Iraq.

From the Call: "If the people of the world are ever to be free, there must come a time when being a citizen of the world takes precedence over being the soldier of a nation. Now is that time. When orders come to ship out, your response will profoundly impact the lives of millions of people in the Middle East and here at home. Your response will help set the course of our future. You will have choices all along the way. Your commanders want you to obey. We urge you to think. We urge you to make your choices based on your conscience. If you choose to resist, we will support you and stand with you because we have come to understand that our REAL duty is to the people of the world and to our common future."

Every active duty soldier today is faced with some very heavy choices. Deciding to do the right thing takes courage, commitment and the knowledge that you won't be standing alone. A little while ago, Carl Dix, National Spokesperson for the Revolutionary Communist Party and a signer of the Call to Conscience took time during a visit to Los Angeles to talk about his experiences as a GI Resister during the Vietnam War. This is Part 1 of a two-part interview.

RW: Let's talk a little about how you ended up in the military.

CD: It was in 1968 and the draft was kicking then. I got a notice to report on April 6, 1968. It was a couple of days after the assassination of Martin Luther King and, with all that was going on, I didn't feel like reporting to the army that weekend. So, I wrote them a letter and said, "I got some other things going on right now and I'm not coming." They sent me back a letter that said, "We understand why you might not want to report during this tumultuous time and we will send you another notice in the near future." A month later two MP's came to my house, delivering the notice to report in June. They gave the notice to my mother and told her that I'd be in big trouble if I didn't show up. So I decided to show this time.

So I'm in the army and the big thing that I'm thinking about and up against is am I going to end up in Vietnam. At that point I didn't know nothing about the Vietnam War so it wasn't like I had a principled opposition to it. But I knew that people were getting shot and killed in Vietnam. So this was not somewhere I wanted to end up.

I came out of the basic training and the advanced training and I got orders to Germany. I didn't realize that we were sent to Germany for some on-the-job training and then we got orders to Vietnam in November of 1969, around the time of this big anti-war march on Washington.

When I got to the overseas replacement station at Fort Lewis, Washington, I decided that I didn't want to go but I didn't know how to work this out. I didn't want to end up in jail so I was trying to figure out how was this gonna go. I figured that I needed to at least delay this. I looked at how they were putting the list together to send people to Vietnam and figured since this was the army there was probably not a centrally generated list of all the people who had orders to go to Vietnam. There was probably a private sitting down with a pencil and a note pad putting together the list.

I found this guy taking your name down as you got your sheets and blankets. I didn't see anybody else collecting a list. So instead of going in the front door and signing up for my sheets and blankets, I went around to the back door and caught one of the GI's turning in his sheets as he went to get on the truck to get on the plane to go to Vietnam. I said, hey man give me your sheets. He said, "Oh no, they told us we had to turn our sheets in." I asked him what they were gonna do if he didn't turn his sheets in--ship him to Vietnam? He laughed and gave me his sheets. So I got bedding and my name wasn't on that pad.

Two nights later they called the whole barracks out and one by one they called off the names of the people to get on the plane to go to Vietnam. Every name got called except mine. My name was the only one that wasn't on the list. These officers who were calling off the list were there looking at me like they know I did something wrong. They don't know what it is but they know that somehow I did something that got myself off that list.

The next day I'm walking along the base kicking a stone when I felt a stone hit the back of my feet. I turned around and looked and there were these other two GI's walking along kicking stones. I said, hey what's up man and they said they had orders to Vietnam and they didn't want to go. I told them that was exactly how I felt and they asked me did I know how to get to downtown Tacoma cuz they had heard there were people there who could help us.

In downtown Tacoma we looked for people who could help GI's with orders to Vietnam but who didn't want to go. We finally ran up on some people and we talked with them. We weren't sure we should tell them we were GI's until we knew if they were against the war too. When we found out they were, we told them we were GI's against the war and we needed some help. They turned us on to some people who told us that we could file for conscientious objector status.

We filed our applications and that got us off the orders to go to Vietnam. Then they had to give us jobs on the base. They found out I can type so they made me a company clerk. I'm sitting in the main office where all the people come through. I didn't have to go to Vietnam but all these people were coming through this office on the way to Vietnam and probably a lot of them don't want to go. I decided that when people came through I would stop them all and interview them. I checked out the regulations on the basis for people to get off orders to go to Vietnam. I took people through an interview and when I found people who fit those categories then I asked them things like, were they the sole support of their family, were they the sole surviving son of a veteran who had been killed, did they have a relative already in the war zone. In addition to filing for conscientious objector status, these kinds of things were the basis to get off of orders to Vietnam.

Then I began to discuss that aspect with them and if I found they were reluctant to go to Vietnam I would say, well, I have to inform you that there is a possibility for you to file an application to get off the orders. You know, it's my duty to inform you of this. I'm not trying to make you do this but you can if you want. We got about 75 to 100 people off the orders to go to Vietnam in the three weeks that I was the company clerk. They noticed this explosion in people filing to get off the orders and they did two things. First they bounced me out of the company clerk's job. And they changed army regulations so that anyone who filed an application to get off orders to go to Vietnam would still be sent to Vietnam for the months it took for the application to get processed. In other words, while you're waiting to see if you don't have to go to Vietnam, you're sitting in Vietnam. They figured that would take the steam out of people filing these applications.

Then they turned down all the conscientious objector applications, every single one of them. We felt this was payback for what we had done so we figured we got to go back at them. We got on TV in the area. We went to anti-war demonstrations and spoke on it. We did this over the weekend and by Monday they came back and said, "It wasn't right for us to turn down all these applications at once. We should have given you all an individual process. So we're gonna allow everybody to refile their applications, and do additional documentation and so on." They were offering us a truce. They wouldn't send us to Vietnam--they would process us endlessly while we got out of the army one by one and then we wouldn't mess with their operation.

We figured ok, we won't go to Vietnam. Then we had a discussion in the barracks. They put all the conscientious objectors in the same barracks so we wouldn't infect the rest of the military since this place was sending hundreds of people to Vietnam every day. There were about 30 of us at that point. There was a lot of discussion and debate about whether we should just accept this truce or did we have a responsibility to resist the war in Vietnam. And if any of us did resist the war in Vietnam would they then revoke everybody's thing and try to send all of us to Vietnam. We had a lot of discussion over that and finally decided the people who wanted to take this on should go ahead and take it on and those who didn't want to would stand back from it. But people understood why some of us felt like we could not accept that truce.

While all this was going on Kent State and Jackson State happened--the National Guard and law enforcement shot down protesting students. That took it over the edge. We felt like we had to step out and become a part of this movement no matter what the consequences were. We hooked up with a local anti- war coalition that was trying to figure out how to reach the GI's. The base was pretty locked down. You had to have military ID or a reason to get on. That meant people were limited to trying to find GI's off the base and handing them some leaflets and trying to get them to take the leaflets back to the base. Most GI's were reluctant to do that because there was a case of a guy who had one flyer and showed it to another GI and he got six months in the stockade.

We took 10,000 flyers. We knew how things got done on the base. If the base got littered the GI's had to go out and pick it up. We decided to litter the base with the anti-war flyers. We got a car, drove through the base and 10,000 flyers went out the windows. Calls went into the base commandant the next morning saying the base is a mess and he's got to get it cleaned up. They got all the GI's out, lined them up and made them go through the fields picking up the anti-war leaflets. People picked up the flyers, saw what they were and then everybody was talking about how the anti-war protesters flyered the base. Word got back to some officers that they got people picking up these anti-war flyers and they said, "Get those flyers away from the GI's." It became a battle -- the GI's wanted to keep the flyers but the officers had given orders to take them back. The protest and the fact that the base got flyered were the topics of conversation on the base for the next couple of days. They had to lock the base down to try to keep GI's from going to that protest. And even with that, a number of GI's broke through the lockdown to get to the protest.

RW: What kind of impact did the anti-war movement have on the GI's?

CD: That had a major impact. That was where a lot of people learned a lot of what they got around Vietnam. The message was coming in about what was really going on in Vietnam and how this war was really about trying to suppress a people's liberation struggle.

RW: So you distributed the flyer and then what?

CD: The anti-war flyer was the first thing we did but we figured we got to go beyond that. There was this brother, Willie Williams, who was facing mutiny charges. He was a GI who had left because his family was in a bad situation and he needed more money than he got as a Private in the army to support them. He went AWOL and got a job to support his family. While he was doing this he hooked up with the Black Panther Party. They finally caught him and brought him back. He formally resigned from the military and they refused to accept it. They were going to put him on trial for desertion. While he was awaiting the trial for desertion he circulated a petition in the barracks demanding freedom for Black people. There were 40 GI's in his barracks and he got 35 signatures.

His charges got upped from desertion to mutiny and he was facing 99 years in prison. We formed the Willie Williams Defense Committee and we went out and spoke at anti-war rallies, we tried to publicize his case. The army was essentially forced to back off of the mutiny charges and just make it desertion and then that was busted down to "Absent Without Leave." Then Willie got a year at Leavenworth.

In the course of doing this we decided that we were going to go for what we thought was the most out there, public thing we could do on Fort Lewis. Every Sunday the local TV station interviewed the base commandant's wife on her way to church. She would say that she was going in there to pray for the boys in Vietnam. Everybody on the base hated this cuz they thought that the commandant had no concern for the boys in Vietnam or the boys at Fort Lewis and his wife probably didn't either. We figured we'd hit this. We got together with a few civilians -- there were four GI's and four civilians. We positioned ourselves right where she came to do this interview and as the camera came up to get her sound bite about praying for the boys in Vietnam we broke into it. We started talking about the Willie Williams case, about the opposition to the war in Vietnam in society and in the military. And then we harangued her with something about how people like her are preying on the boys who are being sent to Vietnam.

We went to our car and tried to get off the base. We delayed too long and got caught. At first they were going to take us to the edge of the base and scatter us out and drop us off. This was the procedure when they caught civilians on the base. But when they found out that four of us were GI's they dropped the civilians off at the edge of the base and they brought us back and put us into custody.

This was on Sunday, and Monday they denied the conscientious objector applications of the four of us who did the action. By Tuesday they denied most of the other conscientious objector applications too, although they did accept the application of one guy so it wouldn't be a blanket thing. The rest of us now had orders to go to Vietnam. We had a lot of discussion about what we were going to do. The majority sentiment was to try going to Canada and that's what most people did. Six of us decided that this was not the step we wanted to take. We had been standing up and opposing this war and we felt that we should stay here and refuse to go to Vietnam.

I wasn't a revolutionary at this point but I did feel that my fight was not in Vietnam, it was here. A lot of that was bound up with the Black Liberation movement that was developing. I had seen the kids in the Southeastern U.S. have the dogs let loose on them, seen them get hit with hoses, as they went against Jim Crow segregation. I had seen the beginnings of the rebellions in cities across the country. I had not been a part of any of that but it all impacted me and I knew that somehow I had a fight here. I didn't know exactly what it was or exactly how to fight it but I did know that my fight was here so I wasn't leaving for Canada.

Six of us decided that we were going to refuse. The morning that the orders were set for I told them I was not going to Vietnam and the first sergeant ordered this guy to get a pistol and rounds out of the weapons room and to shoot me if I make a move. I started to think that this might be a little more difficult than I thought. We had until that night to report but my commanding officer decided he wasn't going to let it go on that long. He pulled a truck up and gave me a direct order to get in the truck. I said I ain't gonna go and I got arrested and taken to the stockade. I ended up in the stockade that morning and one by one the other guys showed up.

RW: You were tried for refusing the orders to Vietnam. What was the outcome of that?

CD: The judge made a point of ignoring anything our attorney raised. He said at one point, "I have to allow you to say this for the appeal but it will have no impact here and if I fall asleep will someone wake me when he's finished." He just wanted to make it real clear that we were going to jail and he wasn't listening to any argument we had. We all got convicted but we didn't all get the same sentence. One guy got three years, two of us got two years; two others got one year and one guy got 58 days. The guy who got 58 days went back to the company and it turned out that the company commander liked him and thought that his only problem was that he had fallen under our sway. He did 58 days, went back to the company and was allowed to stay there. The orders to Vietnam were forgotten. The guy who got three years had his sentence busted down to two.

When you got that much time you usually got sent to Leavenworth Penitentiary in a couple of months. In a few days we were all in Leavenworth except for the guy who got 58 days. They broke records in processing us out cuz they said we were a "cancer on the place."

To be continued

This article is posted in English and Spanish on Revolutionary Worker Online

http://rwor.org

Write: Box 3486, Merchandise Mart, Chicago, IL 60654

Phone: 773-227-4066 Fax: 773-227-4497