The Revolution Interview

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Say Her Name—Highlighting the Stories of Black Women…Resisting Their Murder by Police

May 25, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Revolution Interview

A special feature of Revolution to acquaint our readers with the views of

significant figures in art, theater, music and literature, science, sports and politics. The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our paper.

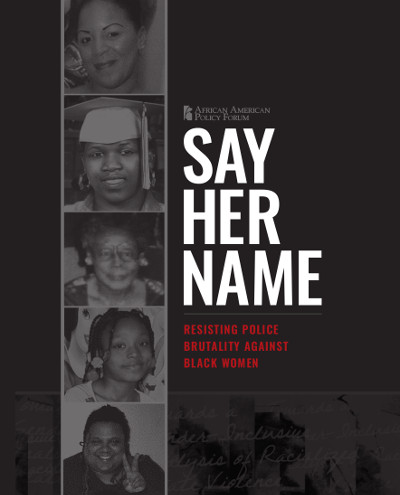

On May 20, hundreds of people gathered at Union Square in New York City for #SayHerName: A vigil to remember Black women and girls who have been murdered by police. This was part of a national campaign, SayHerName, marking the violence and murders of Black women and girls at the hands of the police. There were events held across the country. After the action, Sunsara Taylor interviewed one of the organizers, Kimberlé Crenshaw, for Revolution/revcom.us. Crenshaw is a scholar in the field of critical race theory and a professor at UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School, specializing in race and gender issues. Crenshaw is co-author in a report issued in February 2015 titled #SayHerName: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women. (The report is available online at the African American Policy Forum site.)

Sunsara Taylor: So we had this amazing action today, highlighting Black women killed by police, and I wondered if you could say what drove you to want to organize this, why you felt it was so important?

Kimberlé Crenshaw speaks to SayHerName gathering at Union Square, New York City, part of nationwide protests against police murder of Black women. Photo: African American Policy Forum

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well first we were doing it in solidarity and in response to the call from the Black Youth Project 100 who called for a day of action on May the 21st, to highlight the killing and police abuse against Black women and girls. We have been pursuing a campaign called Say Her Name that corresponds with that call. And in particular we’ve been trying to collect and provide frames for the stories around Black women who have been killed by the police. Our belief is that just saying the facts isn’t enough—we have to basically use the facts to shift the frame. So we wanted to use this opportunity, first of all, as a day of remembrance prior to the day of action, to put forward what the action is about. So we wanted to bring a group of families together to tell the stories of their daughters, to lift the daughters up, and to clearly show a) that Black women are killed and abused by police, b) they’re killed and abused in ways that are similar and can be fit within existing frames, if you just remember to say their names. So they are killed in driving while Black situations. They’re killed when the police see a “look” that they think is suggestive of an intent to harm or kill the police, so the police react prophylactically against Black women as well as they react against Black men. So we wanted to highlight that. And we also wanted to highlight the particular ways that Black women, because they are Black and women, are subject to sometimes unique forms of state violence. So both the ways that they are experiencing similar risks and the ways they are experiencing things that are unique as Black women—we want to lift up both these things.

Sunsara Taylor: Do you want to say anything more about what is unique in their experience?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: One of the things that is unique about gender racism in American society is that Black women are subject to many of the racial stereotypes that people think apply primarily to men, but in fact apply to women as well. So that when Black women are facing some circumstances that they face because of their gender, they a) don’t get any benefit from a patriarchal society efforts to create like “damsels in distress,” right? They’re never the “damsels in distress.” They’re the “angry” Black women, they’re the “scary” Black women, or the “dangerous” Black women. So when the police have been called in situations where otherwise they might be expected to help, they frequently turn those situations into situations where the Black women themselves are being criminalized. Many of the cases that we’ve heard about today, from Michelle Crusoe to Tanisha Anderson, are cases where Black women have been in crisis in some way—families have relied on the state to come in and intervene in a way that’s helpful. And the states come in and ended up killing them. So in these instances we see women being killed in their homes, being killed in their bedroom, being killed in front of their children, being allowed to bleed to death or draw their last breath with the family being kept away from them. This level of inhumanity reflects the convergence of all kinds of ways that Black women have not been given the benefit of being seen as mothers, being seen as people who are loving and care for their children, people who children care for. I mean it’s like the pain and the trauma of an inflicted death is just not felt, not seen, not given any emotion whatsoever. And so we see these as moments where them being women who are Black precludes them from getting the concern they might otherwise get, if they were women who were not Black. On the other hand, the very fact that so many of these women have been killed, and their killings have not been part of the readily available names of victims of police abuse that represent the vulnerability of all of us, is a second level of dynamic of subordination. It’s like, their lives can’t even be lifted up. And what signal is that giving to the state, what signal is that giving to society about the importance of their lives? If they’re not valuable to those of us who care about racial justice—why do we think they would be valuable to people who don’t?

Sunsara Taylor: Yeah. What do you think is driving this epidemic which is coming to the surface now, where people are starting to see, yes, mainly recognizing the men, but also increasingly women. How do you see this epidemic of police murder? Where is it coming from?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: We know that increasingly the police in a neo-liberal state are the piece of the state that does most social work. It’s social work of containment, it’s social work of control. When mental health and physical health and education and other life-affirming policies and practices of the state are withdrawn, it only leaves the police as the main point of intervention for most social kinds of things, right? So you have a shrinking state with respect to affirmative life aspects. And you have an increasing state when it comes to... so now what do you do with people? Well you coerce them. You intervene with discipline and punishment. And then you also have a crisis of policing itself. So you have the role of what the police do. I mean, you have the question of who the actual individuals are. So you have a constant demand for police, and the only requirement is that they are willing to take this role—not that they are competent and capable to take this role. You’ve got a perfect storm, with increasing deployment of the police to deal with mental health, right? To deal with the enforcement of poverty. To deal with other forms of, you know, geographic displacement and marginality. I mean some of the women we’ve talked about, one in particular, was killed basically because she was homeless. So you have the function of the state, not being protecting and serving but to constrain, punish and kill. And you have individuals who are perfectly capable of that project.

Sunsara Taylor: And do you have anything to say about why you think that’s what’s happening? If you pulled back the lens, why is that?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well, you know, it’s not an accident that we have increasing distribution of wealth upward. I mean, that does something. It’s not just, “Oh our paycheck is worth 60 percent of what it was 200 years ago,” and on the other hand we have the greatest level of wealth concentration in our history, dating back to the 19th century—it’s nothing compared to what we have now, ok? So that upward trajectory of wealth actually opens up a whole social sphere of competition, number one. The racial wages of white supremacy become more important when real wages are less significant. And the jobs that are available are jobs of containment and constraint. So two of the most powerful unions in our republic right now are security-oriented— the police...

Sunsara Taylor: ...and security guards...

Kimberlé Crenshaw: ...the police tried to bring the mayor to his knees! For basically saying any father of a Black child would say, right? He’s not supposed to say that. So the mayor is gonna be punished for telling the truth. I think that was a real raw moment, where the power of this union is really made evident. The other moment, you know, is the recognition that one of the most significant factors in resisting efforts to de-criminalize and to reduce mass incarceration, are prison guard unions, right? So here we have sort of a classic working class, race kind of divide, which then is fueled and animated, reflected in a certain right-wing kind of politics that almost reflexively comes out in defense of police, no matter what. You kill an 11-year-old boy—well he should’ve known better than to play with a gun. You kill a Black woman who is in a mental crisis —well, she shouldn’t have given him that look. It’s the being Black while Black kind of, right, kind of...it’s in this environment that that becomes an offense around which you might be killed. So it’s not that we haven’t seen this before. It’s just that we think it’s hyperbole, you know, to talk about lynching as an activity that bonded white working class and white elite people together over the need to contain and control Black bodies, or slave patrols is effectively being an expression of a joint project of containment, even though there are huge class interests that are different between groups of people. So it is not surprising that in this moment, of a Black president, that there would be a convergence of a certain aggressive expression of the need to push down, push back, and control. And the only reason this is even remotely surprising to us is that somehow when a white person becomes cloaked with the state, their expression at that point is as police, as opposed to people with jobs and people who have biases and other kinds of interests who are in a position to actually express that through some kind of lethal force. So it’s not surprising. And I’ll just throw in, of course people will say, well not all the people who engage in this were white. The person that killed...

Sunsara Taylor: ...Eric Garner, there was a Black sergeant...

Kimberlé Crenshaw: ...there was a Black sergeant. But also it was a Black woman who killed the woman in Oakland, I can’t remember her name now. People forget that cultures can be racialized, which means even those cultures can take on the characteristics and logic of the institutions that they’re in. There’s nothing new about that either.

Sunsara Taylor: So I’m going to combine my last two questions. In terms of solutions, in terms of what you think needs to happen, on two levels. Macro, not just next steps, but actually what...you asked everybody, what does justice look like? What does victory look like? And then, relatedly, what do you feel about today, what’s come together, where do you think we’re at in this, where would you like to see this go? So first on real victory, and then where we’re at how do you see going forward.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Real victory is that the role of the police to protect and serve is not just mythical, but it actually is made real. So the goal would be to shift from constraint, containment, and coercive deaths to—actually the police do protect the entire population, and they actually serve that. It’s not unrealistic or a pipe dream, to begin with what kind of society would we have to imagine, where the police did serve that role. And that means that we’re thinking not just about the police but we have to think about it. So what are the institutional-level changes that need to be made in that cultural space so that the values of protecting and serving the population are far more dominant than the value of simply taking control of situations and punishment. So that would have to be, a being that generated concrete interventions. On the micro level, next steps, I would like to hope that after these two days, especially with the multiple actions that are taking place in response to these projects across the country, that it would be impossible to fall back into the tendency of talking about police violence only in male terms. I think that would be a minor victory. Because this is closest to us. We should at least be able to influence those of us who are on the same side of this issue. And second, I would hope that having broadened the frame to include women as well as men, the demands of the movement go beyond topical questions about accountability to substantive things like—body cameras are useful if there is a reinterpretation of what is legitimate or illegitimate force. I mean the Eric Garner case shows that cameras, to catch the facts...

Sunsara Taylor: ...Rodney King...

Kimberlé Crenshaw: ...yeah, this is the story we learned...exactly. So, being able to shift the dialogue, not just on the question of capturing the facts but bringing new meaning to what policing ought to be, what’s justifiable and what’s not. So I think, in fact, including women in some of these narratives may help us reveal the lie in the consistent, consistent...reframe the rhetorical, “They were going to kill me,” “I knew my life was in danger.” And I think it moves beyond the individual level debate—did he or did he not have his hands up, did he or did he not resist arrest—to a broader understanding. These are entire communities that are being held under prerogatives of police departments. Policing is about containment and control, and it still is. So being able to show entire communities, I think pushes against that individualizing thing, to look more structurally at how police actually function in a society that is still organized as one that has deep racial hierarchies.

Sunsara Taylor: Is there anything else you want to add?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Say her name.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.