Interview with Rise Up October Steering Committee Member Nkosi Anderson:

“Hey, enough is enough! We need to put an end to police terror and fight for a better world.”

September 26, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Revolution/revcom.us interviewed Nkosi Anderson, a member of the #riseUpOctober 24 to Stop Police Terror Steering Committee, on September 25, 2015. He is a graduate student of Union Theological Seminary.

Revolution Interview:

A special feature of Revolution to acquaint our readers with the views of significant figures in art, theater, music and literature, science, sports, and politics. The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our paper.

Revolution: You were an early initiator of Rise Up October and have taken a lot of responsibility to build for these three days in October when thousands of people will take a stand in New York City to say NO to police terror. Maybe you could start by talking about how you see the current situation and why you’ve made this commitment.

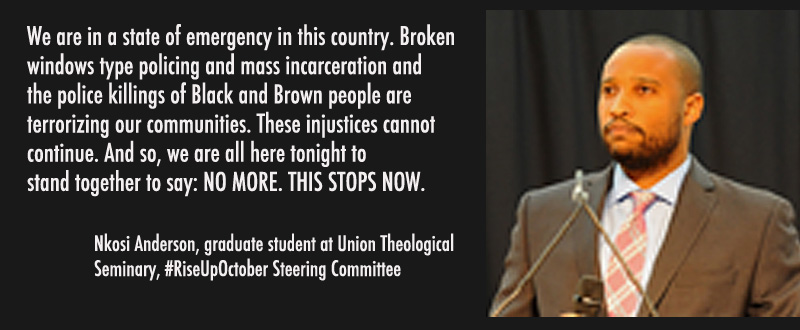

Nkosi Anderson speaking on August 27 at the First Corinthian Baptist Church (FCBC) in Harlem, New York City: What We Must Do to STOP Police Murder and Terror—Get Ready for #RiseUpOctober

Nkosi Anderson: Sure, sure. Well, I think when we try to look at any current social issue or situation we have to first look historically. And so for me W.E.B. Du Bois is a scholar who helps me think through a lot of what we see going on today. [In my talk at the August 27th program to build for Rise Up October] I had made reference to his 1903 classic, The Souls of Black Folk. Now it’s funny with Du Bois, he lived from 1868 to 1963. So we’re looking at 95 years and why I think he’s such an interesting figure is because he developed over all those years. Lots of times you see people, especially as they achieve a sort of notoriety, become more conservative, or almost reactionary. But he became increasingly radical throughout his years. So I say that to say that by the 1930s and later on he had became a full-fledged Marxist in his analysis. He writes his magnum opus Black Reconstruction in 1935; in the early 60s he joins the Communist Party and leaves this country, never to return.

So he is someone who grew increasingly radical. But even in 1903 he is developing this kind of consciousness around the problems of society and the oppression of Black people and the masses in general. There’s a chapter in The Souls of Black Folk called, “Of the Sons of Master and Man,” if I’m not mistaken. And in it he’s talking about the social relations of Blacks and whites after emancipation. And what I found interesting in that chapter is that he says that it became very clear that once Black folks were freed, that the economic system could not accommodate all of a sudden now, all these people who needed to be paid for their labor, as opposed to being enslaved and exploited for their labor. And so the question was, “What do we do with all these freed Negroes?” And immediately, the solution was to use the courts; use the police, to essentially re-enslave these people. And so you were branded a criminal simply by your color, the color of your skin.

Revolution: Like there were vagrancy laws where people were arrested for walking down the street—not literally for being Black, but that was the essence of it, right?

Nkosi Anderson: You go to court and you had no chance of winning any case even if you weren’t guilty. I just found that very instructive that even in 1903, Du Bois in his historical analysis is showing the way the criminal injustice system has always been used as a mechanism of social control. It’s been used to protect the interests of the propertied class. It’s also been used to exploit the masses, poor and working folk, and people of color. I mentioned his 1935 text Black Reconstruction. Well, the first two chapters of that book talk about the Black worker and the white worker, and then the third is the planter. So, in the beginning of that book he’s showing how historically, both Blacks and whites have been exploited by the capitalist class to extract the wealth of their labor from them—but then also to pit them against one another. So instead of saying, “Hey, let’s look what we have united and let’s come together and push back,” they’ve been divided and kept oppressed. And I think we see those same types of dynamics going on today.

I think one of the challenges that we face and maybe I’m jumping ahead of myself, that I’m seeing as I try to organize for Rise Up October, is that there are different perceptions in this country on the role of police and what is actually going on in the street. And so for some folks it’s clear as day—they’re living in cities that are literally being occupied by police forces. But for other folks there is kind of this image that the police are here to protect and serve and sacrifice and do good. And certainly the police actually function that way in certain neighborhoods. The police in say a city like Short Hills, New Jersey—I’m from New Jersey, so a city like Short Hills, New Jersey, which is very affluent—the police are going to serve a certain function in that town which is very different from the function that they’re going to serve 20 minutes away in the city of Newark. So it’s kind of how can we get clarity and an orientation around this issue and I think history can give us some light in that.

Revolution: Maybe you could expand on this by addressing the role of family members who have had loved ones killed by the police. What has been your experience working with these families and hearing their stories?

Nkosi Anderson: I think first and foremost when I think of my experience working with these families, is that I’ve been first and foremost humbled by their deep strength and their deep love. I don’t know what I would do if I lost someone near and dear to me. I’d probably retreat, I’d probably fall into destructive behavior. I don’t know what I would do. And so I’m just amazed whenever I see these families not just lament their own loss but use it as an opportunity to speak out against injustices that are continuing to affect others—saying, “Hey you know what? I’m not going to wallow in my pain but I’m going take a stand in honor of my fallen family member to say that this must stop.” And so for me, I’m just humbled to see that type of courage and love of people for them to do that.

I think also this kind of just crystalizes the importance of the struggle, the importance of trying to work for a new world. People are dying. People are losing loved ones. It can’t continue. It has to stop. And so I think what these family members bring to this effort is that they make it real. It’s not just an intellectual, philosophical debate or political debate. It’s real. Lives are on the line. And I think that for those who may not understand the depths of these horrors that are going on, when they see someone speak about a lost granddaughter, or a lost son, or a lost brother, I think that it creates a level of empathy that just theorizing or detached discourse cannot. People aren’t making this up, this is real. And I think that’s what I think they contribute most to this movement to end this type of police terror.

Revolution: I think you’re pointing to the moral dimension of whether or not one stands aside, retreats into self or becomes a freedom fighter. How do you see that, including the role of your faith in that?

Nkosi Anderson: Well, you know, I think that Chairman Avakian has made this clear and I think this is something that this movement has taken up—there’s a line we have, “Which side are you on?” I think the conditions that we are facing today create a clear moral line. I mean I think when you look at the Civil Rights Movement, what freedom fighters then were able to successfully do was make it crystal clear: “OK, this is the moral issue that we’re facing. Do you believe that a certain group of people should be segregated against, subordinated against, and terrorized based on just who they are? Or do you not? And if you don’t then get with this movement and let’s stop it. And if you do, hey, you know, we’re going to fight back.” And it became clear and folks had to take a stand. And I think that’s why that movement was able to make the gains that it did.

Nkosi Anderson speaks at August 27 event in New York City: What We Must Do to STOP Police Murder and Terror

So when we’re talking about the movement today, it does become a moral question. Do you feel that police should have free rein to kill people—or not? Do you feel that police should have free rein to kill people and not face any form of review or discipline or be accountable in any way whatsoever, or not?

Then of course when we’re talking about police murder we’re also talking about our system of mass incarceration. Do you feel that it’s OK, for this country in particular, to have the highest rates of mass incarceration in the entire world? We are the richest nation in the world, yet we incarcerate more than anyone. Do you feel that it’s OK for us to have a system in this country in which for-profit corporations are able to make money off of the suffering and misery of people? I’m thinking of these prison companies that are making tons of money building prisons to house people, there’s money in that. Or not? And so these are clear moral questions and I think these are questions that everybody has to look within themselves and be honest and say OK, where do I stand?

Now, for me, I come at this as a prophetic, as a revolutionary Christian. That’s kind of my grounding, the tradition that I come out of. So we have people like Martin Luther King Jr. who fall into this tradition. You have people like the great social gospeler, Walter Rauschenbusch or the great Black Christian socialist, George Washington Woodbey. He’s someone who I’m actually writing my dissertation on. He’s one of the leading Black socialists in the early part of the 20th Century. You have people like Cornel West coming out of that tradition. It’s saying that, hey we have a call to confront evils across the board. And so you can’t just be like, oh, I’m only going to look at racism. I’m only going to look at environmental destruction. No, we have to be consistent in our morality. So we have to fight against the oppression of women. We have to fight against transphobia and homophobia. We have to fight against poverty. We have to fight against the xenophobia and the bigotry of people like Donald Trump and these other repugnant people. So we’re called to stand on the side of justice.

But I also come out of the Black Freedom Movement. And honestly at the end of the day, wherever our orientation is, whatever our ideological backgrounds are, at a fundamental level, it’s a human thing. Are you OK with seeing your fellow human beings suffer, or not? Do you believe that the way things are right now is good enough? Or do you think that we need to stand together to push for a radically different world? And so when you start asking those types of questions I think that it opens up the conversation and it opens up ground for solidarity.

I look at the relationship between Cornel West and Carl Dix—or we can even extend it to the Dialogue at Riverside Church between Cornel West and Bob Avakian, for example. Here you have folks coming from perhaps different orientations—revolutionary communist stream, prophetic revolutionary Christian stream. But they have overlap around some of these central moral questions and so in that sense they are able to build and able to say, “Hey OK, we agree on these issues of morality, let’s stand together and fight for a radically new world.” And so I just think at a bare level, that basic human level of what type of person are you going to be, regardless of your ideological or religious orientation, what type of person are you going to be and what do you want for your fellow human beings and the natural world. These are moral questions and folks have to take a stand given the conditions that we’re in today in our society.

Revolution: So how do you see Rise Up October, the 22nd, the 23rd, and the mass, massive convergence in New York City on the 24th, impacting the situation?

Nkosi Anderson: I think for me there’s always a need to simultaneously put forth a pragmatic kind of fight back, kind of reformist, broadly speaking strategy, on the one hand; and at the same time, always advance an idealistic, forward thinking revolutionary vision. So what do I mean by that? I think that our work has to be about trying to push back against police murder, against broken windows type of policing, against mass incarceration. That’s the thrust of Rise Up October, that’s the thrust of the Stop Mass Incarceration Network. We want to pour into the streets of New York City and we want to say, “Enough of this, this must stop now!”

And so for October 22nd, 23rd, and the 24th we’re trying to create as many opportunities as possible for people who see things the same way to come out and let their voices be heard. So on the 22nd, for example, we’re going to have a public reading of the names of those who have been killed by the police in Times Square. We’re going to enlist religious folk, celebrities, family members, a wide range of folks, to come and give kind of a public witness, as we say in the church, of these people who have died—in Times Square to draw attention to this. The next day we’re having non-violent acts of civil disobedience, to go back to that long tradition of non-violent civil disobedience in this country that has brought about change—which we saw in Ferguson, for instance a year ago and in Baltimore. And then we’re also having marches; we’re also having speeches.

So we’re having a variety of different activities and we hope everybody comes out and participates in all this. We hope people will try and plug in and let their voices be heard in a variety of different ways. And again, the goal is to say, “Enough is enough!” We don’t want broken windows, stop and frisk type of policing. We don’t want police killing people and not being held accountable. We don’t want millions of our brothers and our sisters rotting away in prisons. We want to put an end to this NOW. And so that’s the pushback strategy, that’s the practical, kind of immediate, pushback strategy.

But going on beyond that, my hope is that Rise Up October is just another step in the push towards a more revolutionary kind of vision and action, a more kind of grand, more radical remaking of this society. The way things are right now is not good enough. There has to be a better way. And so for us to get there it’s going to take all of us working together to radically remake our world. And so I think that’s what I hope comes about after Rise Up October, that this can just work towards building momentum towards a kind of more transformative stage in our human development.

Revolution: In going out and building for Rise Up October, there is the need to challenge white people, Black people, everyone, to take a stand around stopping police terror. Maybe you could talk some about this.

Nkosi Anderson: Well, a couple of things. I guess first just immediately responding to your issue about the needing to push white people on this issue. I mean, there was a study that came out a few weeks ago, which looked at the attitudes of Black and white people in response to this issue of police terror. And predictably a high percentage of Black people felt that the police were a problem. And sadly predictably those numbers were much lower among whites that they interviewed. So certainly there is this kind of “race gap” that we need to work around. And I think this comes again from education, it comes from pushing on questions of morality, expanding people’s ethical framework, developing empathy, developing ally-ship. But developing solidarity and not just saying, “OK, I’m sorry what’s happening to people of color.” But actually saying, “OK, I see myself in you and so I have to take a stand because I don’t want you to be going through what you’re going through just based on your race.”

So certainly that’s something that we have to keep pushing on. And I’ll also say this, there’s also the question of class. So when you look at the Civil Rights Movement one of the gains was that it opened up economic and professional opportunity for a slice of Black life, so you see an emerging Black middle class. Unfortunately...

Revolution: And even a president....

Nkosi Anderson: Well, exactly, you read my mind where I’m going with this. So you see, whereas historically in the Black community, and this was a large reason why we were able to make it through all that we’ve been through, there’s kind of been this idea of linked fate and solidarity—we work together to lift each other up. But what you saw was kind of a professionalization of a slice of Black life—the doctors, the lawyers, the educators. And a lot of them moved on with their careers and forgot—oh wait a minute there’s a responsibility that I have to the rest of our community. And so why do I bring this up? I think another issue that we’re facing right now as we try to promote Rise Up October is this class divide.

There are a lot of affluent, well-to-do Black folk out there who are detached from what our brothers and sisters, walking out here in Harlem or down in Baltimore or out in Ferguson, are going through. “Well, you shouldn’t have talked back to the cops. Well, what were you doing walking on the street? Well, what were you doing playing in the park?” So there’s a disconnect. So my point is we need to work against this kind of racial gap. But we also need, even within Black America, we need to work against some of the class gaps. And I think you see this embodied in the president.

The history of Black strivings in this country has been holding, in particular, the federal government accountable, speaking truth to power. That’s part and parcel of the prophetic tradition. Speaking truth to power. “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” That’s Frederick Douglass. But ever since 2008 with the Obama presidency, we’ve kind of strayed from that tradition. There’s kind of been this symbolic victory of a Black president in the White House, which is very important, we cannot minimize that. But on many levels it’s remained symbolic.

What’s the point of having a Black face in a high place if we’re not going to get some structural change as a result? And sadly, while the President has been pushed - now, of late he’s speaking a little bit more to racial issues and issues of criminal justice and so forth. I think in many respects he’s thinking about his legacy. But too little, too late. And furthermore and I’ve heard Dr. West make this point, you can’t have moral legitimacy when for the previous six years you’ve done everything to increase criminalization in this country. You can’t call for peace when you’re dropping bombs on other countries. You can’t say these things and have any sort of...

Revolution: I think Dr. West has used the term “war crimes.”

Nkosi Anderson: Exactly, oh, they’re definitely war crimes. How can we expect you to put forth fair immigration reform when more immigrants have been detained and deported under your presidency than any other before? How can we trust you to defend law and order or civil liberties when all your administration has done is crack down on whistle blowers, suppress civil liberties...

Revolution: During the Obama Administration every single time a case of police brutality has been brought before the Supreme Court, the Justice Department has defended the killing; including in cases like where the police illegally knocked down the door of a mentally ill woman and beat her. This is with a Department of Justice that was headed by the former Attorney General who talked about being “pro civil rights.” But the record speaks louder than words.

Nkosi Anderson: Exactly, the record speaks louder than words. When I was growing up that’s how my father taught me to engage politics. He said, “Don’t get caught up in the lofty words and the professional image that these politicians put out there. What type of policy are they putting forth? What are their actions saying?”

But just to wrap the point up, I think now we’re seeing some of the contradictions. Folks cannot deny the contradictions. So the vacation’s over. This is still a very racist country and I think when you see folks rising up in Baltimore and Ferguson and so forth—people are taking to the streets and saying enough is enough, we can’t just leave it in the hands of these false messiahs, these elected officials, these leaders who we think are going to take care of the work. No, we have to be the authors of the world that we want to see. And so I think it’s great seeing people rise up.

I was listening to a videoconference this afternoon with one of my mentors, a great activist for many years against poverty and homelessness, Willie Baptist. He works with the Kairos Center and the Poverty Initiative here in New York City. He cut his teeth during the Watts Rebellion in 1965. He was making a point that when the contradictions of the system are most glaring, meaning when economic exploitation and poverty and things are most intense, extreme—simultaneously you’re going to see folks rising up, but you’re also going to see an increase with police repression. And so with Watts that’s what was happening. You had these economic conditions bubbling up and then boom, you see this kind of very reactionary, racist police crackdown of the people and you also see the people rising up.

So here we are seven years after the 2008 recession and I think some of the contradictions of the capitalist system are clear for more and more people. We know the contradictions are always present, but I think in this moment they are highlighted and folks see them. What have we seen? We’ve seen stop and frisk, broken windows type policies. We’ve seen police murder. These things have always gone on but we’re seeing them exacerbated in this moment. But just like in Watts, we’re also seeing people rise up. And so there are lessons in history, whether it’s the Watts Rebellion, whether it’s going back to Du Bois and looking at Emancipation and Reconstruction. There are lessons in history that we can study to help shed light on our moment.

Revolution: Could you speak to those who are reading this, and weighing how much they should throw in for Rise Up October? What would your advice be?

Nkosi Anderson: What I would say to readers of revcom.us and Revolution newspaper—one, you’re in the right place, ok. Louis Althusser speaks of the kind of ideological state apparatuses that oppress us. So plainly put, in our world today, it’s tough to find accurate sources of information and news that go beyond just color commentating or serving the interest of these corporate political parties; that kind of cutting edge truth-telling that should be a fundamental element of journalism. It’s pretty much vanished in this world. And so Revolution newspaper is at the forefront and the cutting edge and is invaluable in terms of being a resource that stays true to this calling—to tell the truth, to inform the people and to really lift up the voices of the people. And so I would say that I think the newspaper is both a voice for the people in terms of the types of articles y’all run, the types of education that y’all disseminate. But it’s also a paper of the people and that y’all are also lifting up the voices of the people in the prisons, of the people on the street, the people in the classrooms. So it’s a paper for the people and of the people.

And then I’d also say to your readers that I think also supporting Revolution Books is connected with this mission. Again we are in a world that is growing less and less literate, that is more prone to mass distraction and spectacle and foolishness. And so it’s vital that we have a bookstore in existence that is providing the type of literature that you’re not going to find elsewhere. You know? So, where are we gonna read about Mao? Where are we gonna read about Marx? Where are we gonna read about Cornel West? Where are we gonna read about Avakian? Where are we going to have a place that disseminates this type of vital literature that we need, to light our way as we go forward in fighting this madness that we see in our world today? And so I think your readers should continue to support and be connected to Revolution newspaper, revcom.us, and Revolution Books.

Revolution: I really appreciate that and your insights on the role of Revolution/revcom.us and Revolution Books. But I did want to hear what you have to say to people who are trying to decide whether or not to throw in with Rise Up October. There are all kinds of things that can seem like obstacles to this challenge of stepping up to make and change history. So what would you say to someone who is weighing that challenge?

Nkosi Anderson: Well, I think it’s exciting. So I think of myself. I’m a student. I’m in the faith community. I’m in New York City. I’m someone with an interest in politics and changing the world for the better. And so this moment allows me to kind of be true to all of those facets of who I am. So I say that just to say, when you look at the great struggles for justice and change in this country, you had to have the participation of students, you had to have the participation of the faith community, you had to have the participation of folks who wanted to change the world for the better and then fight for something good. And so if that is you, this is a chance for you to meet the challenge of our moment, just like those who came before us tried to meet the challenge in their moment.

I think that this is an exciting network that we’re mobilizing—people from, again various different spheres and segments of society with different orientations and different perspectives, but who are all saying, “Hey, enough is enough! We need to put an end to police terror and fight for a better world.”

So I hope people can look at this movement as something that’s welcoming, that’s saying, hey, we need all hands on deck and that people feel they can come and play an active and vital part in it—and also to contribute financially. For some of us we may not be able to be in New York or we may not be able to make it that weekend. But perhaps donating or working to help secure transportation for someone who wants to come down from Boston or up from Washington, DC and be a part of that weekend. There are a lot of different things that can be done; that need to be done in order for this event to be successful. So I think we extend that invitation for people to get with this and to join.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.