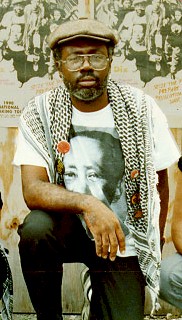

Carl Dix

Revolutionary Worker #1189, March 2, 2003, posted at http://rwor.org

In early January a very powerful and moving "Call to Conscience to Active Duty Troops and Reservists" was issued by a group of veterans of the U.S. armed forces. These vets came from many different political perspectives and from different wars--from World War 2 on up to the 1991 Gulf War. More than 550 vets have signed the Call so far and they include well-known people like Howard Zinn and Michael Moore. One thing unites them all: staunch opposition to the U.S. plans to launch war on Iraq.

From the Call: "If the people of the world are ever to be free, there must come a time when being a citizen of the world takes precedence over being the soldier of a nation. Now is that time. When orders come to ship out, your response will profoundly impact the lives of millions of people in the Middle East and here at home. Your response will help set the course of our future. You will have choices all along the way. Your commanders want you to obey. We urge you to think. We urge you to make your choices based on your conscience. If you choose to resist, we will support you and stand with you because we have come to understand that our REAL duty is to the people of the world and to our common future."

Every active duty soldier today is faced with some very heavy choices. Deciding to do the right thing takes courage, commitment and the knowledge that you won't be standing alone.

Carl Dix, National Spokesperson for the Revolutionary Communist Party and a signer of the Call to Conscience took time during a recent visit to Los Angeles to talk about his experiences as a GI resister during the Vietnam War. In Part 1 of this interview, RW 1188, Carl told the story of how he became one of the Ft. Lewis 6, and how he was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth prison for refusing orders to Vietnam. In Part 2, Carl talks about doing revolutionary organizing in prison and the impact of the anti-war movement on GI's.

RW: Here you have a base whose main purpose is to ship guys off to Vietnam and then you have six guys who refused to go and who have the potential of having a huge impact on the other troops. Not surprising they wanted to get rid of you as quickly as possible, especially since you weren't giving up and quieting down even after they convicted and sentenced you. What happened once you arrived in Leavenworth?

CD : I was pretty scared of Leavenworth. The stockade was like boot camp again, not much worse than that except that you were locked in at night. But then again, at boot camp you didn't dare go out at night either, most of the time. I didn't know what I was going to face at Leavenworth.

I decided to check out who was there, and the first person I fell in with there was Willie Williams. He got sent there from the stockade at Ft. Lewis before we got arrested. Through him I met some other people and then we met some of the newer people coming in. We began to talk about what's going on, what are some of the issues and what are things we can do. We found out that there had been a long struggle for a Black History class at Leavenworth and we decided to take it up. We could move on it and a lot of people in the prison wanted it, so it would give us a network of support. But also, we figured if we got it, it would give us some freedom to do some things. We could go into the class, and since the guards wouldn't be running the class you'd be able to do some stuff.

So we contacted the Black Student Union at the University of Kansas because we knew they were tight with the Black Panther Party. But we also knew they were a legitimate student organization and we were going to try to get hooked up through them.

We decided we needed to find somewhere to have these discussions that were less under the noses of the guards. We scouted and found that there was one area where we could legitimately be inside the prison but where the surveillance system wasn't working. The cameras had somehow gotten disabled and never got repaired. We held our meetings there. Sometimes only the core was there but other times there were also people who just wanted to kick it. There were about 50 people at some of the meetings and then only a half a dozen or eight people at some of the other meetings.

We also broke through on something else that was important. When we came into the prison it was strictly segregated. And that was by the prisoners, not by the guards. You went into the lunch room, you went to watch TV, you went to the game room, the Blacks would be in one place, whites in another and Latinos in another. And there was very little mixing. We were actually able to break through that, and part of the reason we were able to break through it was that of the five Fort Lewis 6 people who came to Leavenworth there were three whites, one Chicano and one Black and we hung together. We also hung out with other people but we hung together. People would ask us why. Blacks would ask me why I was hanging out with those white guys, and they would get approached that way too. We said we're friends and we're together in the struggle. We were together in what got us here and we're not gonna split up just because that's the way things go here.

In place of the strict racial segregation, we got political breakdowns. There would be a core of radicals who would hang together irrespective of nationality. There would be the Black nationalist camp, which on some issues would work with the radical camp and then on some others wouldn't. There was still a Chicano camp but on a number of issues they would unite with the radicals and with the Black nationalists. We were actually able to build a multinational grouping to fight for this Black Studies program.

This was a very important advance because as long as it was just something the Black prisoners wanted then the commandant had an easy way to deal with it. He would say he couldn't do something that was just for the Black prisoners and that would be something the other prisoners wouldn't get. So we pushed forward on this. We didn't get the hook-ups with the students from Kansas and we sent out some other letters. We got a response from the Black Studies Department of the University of Missouri. We went to the commandant with it and he said that he couldn't do this because it was something for the Black prisoners.

Now, we had actually done it this way on purpose. The Black prisoners raised it and we had the whites and Chicanos in reserve. We wanted the commandant to give a reason for turning it down and we expected that reason. So we said, oh you didn't know that all the prisoners wanted this? Then white prisoners and Chicano prisoners and Native People all came forward and said that they wanted this Black Studies program. They said that they felt that we were shortchanged in the American educational system and we all wanted to learn the history of Black people. Everybody was ready to make these arguments about why they wanted it and the commandant's reason for not going forward was flanked by this development. But he still refused to do it.

A little later they came through and arrested 50 people in the prison. They swept through the prison, cracked open your cell, grabbed you, took you out and took you to the hole. They had to open up a new hole. There was a part of the prison that hadn't been used for a couple of years, and they set it up as an emergency solitary situation. But it wasn't really solitary because they had 50 of us down there.

They were aware that we were going past their surveillance to have our meetings. They didn't know what we were discussing, but they thought it was something that would be detrimental to them. They knew who went past their surveillance on a regular basis and that's where they got their 50 people from. They held us for a while and then they took people in and subjected them to interrogation to try to find out what it was we were planning.

When we got taken down to solitary we thought that the worst could happen. That wing of the prison hadn't been used for a couple of years because the last time it was used a prisoner had been murdered there. The official story was he had hung himself, but when his body was taken out it had bruises all over it. So it was clear that a beating had been administered.

RW: We talked about the relationship between you GIs and the anti-war movement at the time. Well, one of the things that always seems to come up big in the anti-war movement--especially in the last Gulf War--is the issue of supporting the troops. And it will probably be a big question now. Already some people are raising that as a given--"of course we have to support our troops"--and as a restraint on the movement. How did that play itself out in your situation and how do you view it today?

CD:Well, I valued the role that people opposing the war in Vietnam played. If it weren't for them, I would not have been able to do what I did. To me that was the best move I ever made. Going to Vietnam and being part of the United States' attempt to drown the liberation struggle of the Vietnamese people in blood would have been the worst mistake I ever made. I needed the exposure that I got from occasionally reading the Black Panther Party newspaper, seeing the anti-war protests on TV, searching out the protesters and talking to them, finding out why they were against the war--I needed that kind of information and exposure to get to the point where I could make a decision on whether I should go over there and fight or was my fight right here. But I also needed that example of resistance to be able to develop the strength to do what I did. So when I speak to people I thank the anti-war movement for helping me to come to the right decision and refuse to go to Vietnam.

At one point a lot of sentiment in opposition to the war in Vietnam developed inside the U.S. military. In fact, it got to the point in Vietnam where they could no longer field U.S. troops as a reliable fighting force. When I was going into the military they were talking about the different ranks and what our tasks would be. But they also talked about life expectancy--how long do people in a particular position usually last before they become casualties. The position that became casualties the quickest were second lieutenants. We always thought it would have been the grunts, the infantrymen, but it was second lieutenants. The army told us it was because second lieutenants often had forward observer duty, and the enemy was targeting them because of the bars on their shoulders and so on.

We found out later, though, that part of the reason second lieutenants had such a high casualty rate is that they were the ones in the field commanding the troops and a lot of the time the troops were pretty determined to avoid combat and the second lieutenants were determined to lead them into combat. There would often be disagreement between the two positions and the army is not a democratic organization-- people didn't get to vote so they developed other ways of overriding the attempts of the second lieutenants to take them into combat. A lot of those second lieutenants got hit by what the military calls friendly fire-- though it wasn't so friendly. They got fragged; some of them got shot in the back trying to lead their troops into battle. Some of them got shot face up when they were trying to force their troops to go into battle.

So there was a point where the military was no longer a reliable fighting force in Vietnam. Part of how that developed was that the sentiment against the war and the revolutionary sentiment that was developing throughout the U.S. permeated the military because it was drawn from average, ordinary people in society--and especially drawn from the oppressed. And the development of things like the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords Party--the Puerto Rican revolutionary party--and revolutionary groupings among the Chicanos had an impact among the GI's. To me it was the resistance movement throughout society that was helping GI's to see what the war was about.

There was also the direct experience of the GI's as part of this. When you are over there, you realize that you are fighting a whole country and that all of the people there seem to want to oppose what you're doing there. This got some people to thinking about what motivated the Vietnamese people. What made men, women and children fight against the U.S. military machine, at that point the mightiest military machine in the world? What made these people without sophisticated weapons put their lives on the line to force the U.S. army out? It made some GI's think, and some of them learned some stuff off of that.

There were a lot of brothers from Nam who told me about things they did that they weren't proud of. When I hooked up with Vietnam Veterans Against the War there was a lot of testifying about this.

The other important thing I found out from talking with GI's who were in Vietnam was the way in which the Vietnamese people's resistance would try to raise these questions with the GI's, especially with the Black GI's. I talked with a lot of Black GI's who told me that their first Black History lesson was in Nam and they got it from the VC. They would run into Vietnamese who had essentially overpowered them and had their lives in their hands and instead of killing them, the Vietnamese asked these soldiers why they were there fighting against the Vietnamese people when Black people were being suppressed in the U.S. They wanted to know why the Black GI's weren't back in the U.S. fighting with their people instead of fighting to suppress the Vietnamese people. This had a huge impact on some people. Here was "the enemy" raising to you where your fight really was and you feeling like they were right.

RW : In terms of today, what would you say are the most important things that you can take from your experience as a GI resister during the Vietnam War and say to GI's today?

CD:The most important thing is this: what is the nature of the war that you are being called on to fight. That's the most important thing and it is the most important decision that people have to make. They have to make it not by listening to the government, not by listening to the mainstream media, but they have to dig for what is this actually about. You can't accept George Bush saying that we have to go to Iraq because Saddam Hussein might have weapons of mass destruction. Hey, George Bush has many more weapons of mass destruction than Saddam Hussein. This is not about weapons of mass destruction. You have to get down to what this is about. And when you get down to this, you will find that this is an unjust war. It's not exactly the same as Vietnam because we're not talking about Iraq as a revolutionary country. It's not the U.S. trying to suppress popular revolution. But it is the United States trying to exert its domination over a very crucial section of the world and planning to slaughter hundreds of thousands of people to exercise that domination. That's an unjust war and my take is that you should not want to be a part of it. That's what I decided in the 1960s. Now people have to decide for themselves, but an unjust war is a war that should not be fought as far as I'm concerned. This is the most important thing I would say.

The other thing I would say, and this is irrespective of whether people are in the military, it is very important that there be a movement of resistance throughout society. Just as I needed a movement of resistance to find out what Vietnam was all about because I couldn't rely on the authorities, the government, the military, the media to tell me, people need a resistance movement that is kicking out the real deal on what the war is about. They also need that example of resistance because people are going to be faced up with a tough choice just like I was faced with a tough choice.

In L.A. people told me that there are many more military recruiters in the high schools than there are college counselors and that says something about the future this system has in store for youth. People need to know what the situation is.

And a third thing--I talked about how I had to deal with the question of whether my fight was in Vietnam or was it here and I decided that my fight was here. Initially I didn't know what that fight was. I knew I was against the Vietnam War, I was against the way that Black people are oppressed. It took me a while to understand that both of these things stem from the nature of this system and the way in which capitalism works and what is needed is a revolution. And it was after that when I became a revolutionary and a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party.

Well, youth today face these same questions. George Bush said about that we have to fight this war on terrorism to keep this way of life in effect. People have to ask themselves what is this way of life he wants to keep in effect.

It is a way of life that people should be fighting against and fighting to get rid of. And the way to do that for real, once and for all, is through revolution, to overthrow this system and go on to build a whole new society on the ashes of this messed-up one. That's the challenge that the youth of today face.

I know that is a lot to lay out on people but what we do say that people can and must do is to grapple with the nature of the war we are being called on to support and fight. If it is unjust then we have to resist it and we have to resist it going as far as we can in that resistance. And in the course of doing this we want to exchange our revolutionary perspective and hear other perspectives. But we are pretty sure that our analysis is right and that it is the nature of this system that is driving us and the world towards war.

This article is posted in English and Spanish on Revolutionary Worker Online

http://rwor.org

Write: Box 3486, Merchandise Mart, Chicago, IL 60654

Phone: 773-227-4066 Fax: 773-227-4497