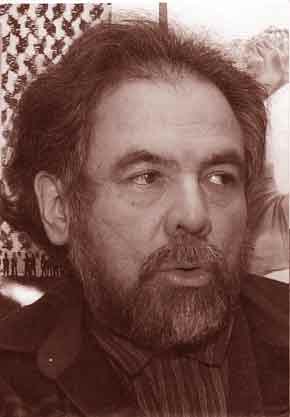

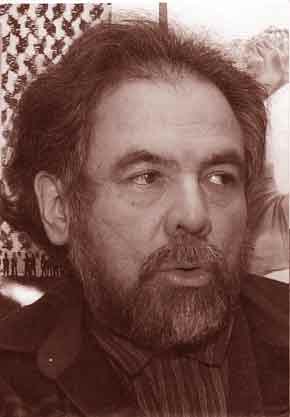

Farouk Abdel-Muhti

|

|

Farouk Abdel-Muhti |

|

Aug. 9, 1947 - Jul. 21, 2004

|

| Photo: Osvaldo Pérez, courtesy of El Diario-La Prensa. |

Revolutionary Worker #1258, November 14, 2004, posted at http://rwor.org

On July 21, as he finished speaking at an event in Philadelphia called “Detection and Torture: Building Resistance,” former political prisoner and much-beloved Palestinian activist Farouk Abdel-Muhti collapsed and died.

It was a shocking and terrible loss for the people – coming just two months after he finally got out of the clutches of Federal immigration authorities. He had been held for 718 days — almost two years. He had been the target of repeated mental and physical abuse. He had survived 250 days in solitary confinement and was subjected to continual verbal abuse. Despite a long-standing and well-documented need for blood pressure and thyroid medications, the prison guards had repeatedly kept these medications from him. The extent to which his mistreatment in prison contributed to his untimely death may never be known. What is known is that he was a fighter for the people to his last breath.

How can I begin to describe what we have lost with the death of this courageous comrade? I knew Farouk for more than a decade, and his death hit really hard.

I remember the day that I first met Farouk – October 11, 1992, at a cultural program to oppose 500 years of genocide, oppression and colonialism in the Americas that began with Columbus. He was a striking figure at the gathering – a Palestinian militant speaking passionately in Spanish, not only for the liberation of the Palestinian people but also in support of revolutionary and progressive struggles throughout the world.

The event occurred only a few days after the capture of Abimael Guzman (Chairman Gonzalo), the leader of the Maoist people’s war in Peru, and the worldwide campaign to “Move Heaven and Earth to Defend the Life of Chairman Gonzalo” was just beginning. Upon hearing the news, Farouk immediately threw himself into this battle, enlisting progressive Palestinian organizations to the cause. Over the next ten years, our paths crossed again many times. If there was an important political battle of the Palestinian people or others to be supported, one was certain to find Farouk there.

Heavy challenges were placed on the people with the events of September 11. In the face of efforts by the power structure to demonize the just struggle of the Palestinian people and target immigrants, Farouk stepped forward even more. He became a regular figure at WBAI on the Morning Show, facilitating and providing translation for phone hookups with activists in the West Bank and Gaza that were heard by many thousands.

When the U.S. government rounded up over 1,200 Arab, Muslim and South Asians, Farouk agonized and strategized. How to rally the broadest possible support to free them? How to unite both Muslims and non-Muslims? Farouk made clear his opposition to religious fundamentalism, and he was for building up the secular pole of resistance. But he also saw the need to forge unity with Muslim activists. How to forge unity between the people in the U.S. and the victims of the global rampage of the U.S. imperialists?

He became deeply involved in the struggle to free the detainees and played a prominent role in organizing the first National Day in Solidarity with Arab, Muslim and South Asian immigrants on February 20, 2002. A little over two months later, he himself became one of the detainees for whose release he had been forging a movement.

Like so many others in detention, Farouk was never charged, let alone convicted, of any crime. But his case had special significance – he was a widely known Palestinian activist, and his imprisonment was aimed at not only silencing him but instilling fear among other activists, particularly immigrants.

Due to his firmness and that of his many supporters, Farouk’s imprisonment had just the opposite effect. An active movement grew in his defense, and despite the harsh conditions and his health problems Farouk found ways to organize other prisoners and wrote messages of support to anti-war marches, striking miners, Chileans marking “the other September 11” (the U.S.-backed coup in Chile in 1973) and others. The authorities kept moving him to new prisons, trying to break his connections with other prisoners and to make him more and more inaccessible to his supporters.

Farouk told the RW in an interview six weeks before his death, “I see by my own eyes the torture of other detainees. Like for months in the Bergen County Jail, the guards [attacked] a Chilean and break his arms and after [that] deport him. I see by my eyes a Palestinian beat up about four or five times. And I see in Hudson County Jail the guards run over an Egyptian and break his teeth. And he’s still in the jail...

“I’ve been in nine different jails. And in these nine different jails, I’ve been tortured, I’ve been beat up, I’ve been oppressed; I’ve been on a hunger strike. And my struggle has not just come to be a part of my personal independent living of myself or about just the people of Palestine or the Arab people and the Mideast people and the South Asian people. But it’s coming to be the problem of all immigrants.”

Like so many prisoners locked in the hell-holes in the belly of the beast, the Revolutionary Worker became an important life-line and organizing tool for him. He made special arrangements to get both the Spanish and English editions of the RW, and he put them to good use. He told me later that he saw the Spanish edition as a kind of a “bridge” between the post 9-11 detainees who spoke no Spanish and the large numbers of Latin American immigrants awaiting deportation for minor infractions. They were side-by-side in the same prison but knew little of each other’s oppression. He said the Obrero Revolucionario helped break down language barriers and build solidarity among the Spanish-speaking prisoners about the Palestinian struggle and opposition against the juggernaut of war and repression. He told the RW: “After I read it, I gave it to the prisoners.... There has to be a linkage between the struggle of our resistance...against the occupation and linkage with the struggle of the working class in the United States against oppression, racism, and what is taking our rights .... [We had] many discussions and debates about the principles, especially on the question of Iraq, which you have covered very well.”

During a search of prisoners’ cells in Hudson County Jail while it was on lockdown, guards discovered in Farouk’s cell copies of the Revolutionary Worker and literature of other leftist organizations. Farouk later told the RW that the guards yelled, “You are a communist, you are un-American,” and beat him up – an act witnessed by other detainees. Farouk was slammed against the wall several times. His lawyer said, “I talked to him a week later, and you could still see his bruises, bright red marks on his legs from where he’d been knocked to the ground.”

Through the efforts of Farouk’s defense committee and legal team, a howling contradiction involved in Farouk’s imprisonment was dragged out into the light of day. The authorities had tried to claim that they were not holding Farouk for political reasons—they were simply holding him until he could be deported for “immigration violations.” But to WHERE might they deport him?

Farouk’s case became a sharp exposure of the plight of the Palestinian people – denied their homeland by the U.S. and their Israeli attack dog. In legal terms, the government faced a dilemma in trying to deport Farouk. Farouk was born in what is now the West Bank, near Ramallah, in 1947, when it was under British colonial rule. He left as a teenager in the early 1960’s, when it was under Jordanian control. Israel, which controls the West Bank today, will not issue travel documents to Palestinians not present there when the Israeli military invaded in 1967 or to Palestinians born there since—making Farouk a "stateless person." Put simply, there was nowhere to deport him to.

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Zadvydas v. Davis that the government cannot hold immigration detainees indefinitely if there is no reasonable likelihood of deporting them. With the six months “time limit” long past and with no expectation of finding a country to which to deport him, a Pennsylvania judge ordered Farouk’s release.

But in an effort to “disappear” him within the U.S.’s vast prison system, right after the judge ordered his release, Farouk was suddenly moved to a regular federal prison (not an immigration jail) in Atlanta – over 800 miles from his supporters. His prisoner number was also changed, making it impossible for his lawyers or supporters to find him. He was finally able to call a supporter on the outside, and he was released on April 12.

*****

Immediately upon his release, Farouk stepped out again. He resumed his presence on the airwaves – again hooking WBAI listeners up with the West Bank and Gaza and joining a new Spanish-language team at the station.

At a moving reception/celebration for Farouk upon his release, a member of his legal team, Shayana Kadidal, shared Farouk’s sentiments: “Tonight, let’s celebrate, but let’s not forget the people in indefinite detention [because of] a government that thinks there’s nothing wrong with imprisoning people indefinitely because of an accident of their birth.” And, indeed, Farouk continued this fight till the day of his death.

As Farouk told the RW: “What I share with all the people in this great city and throughout the country and the world is that the fight against oppression, discrimination and imperialism, which exists at the forefront and as the main objective of this corrupt administration of George W. Bush, certainly there exists an important link between our struggles against the corrupt administration and the side of justice and right for the oppressed people and the workers worldwide – from Harlem to San Juan to Baghdad to Palestine to Caracas to the villages and refugee camps of Palestine and throughout the Arab world. We extend our struggle and our solidarity and our hand to all those brothers and sisters worldwide who endure oppression, discrimination, injustice, torture and brutality under the New World Order of neo-imperialism that exists under the pretext of the war on terror.”

I had the good fortune of running into Farouk about a week before his death. He was on his way back from visiting one of the very prisons where he had been held prisoner – to strengthen ties with and support for the prisoners who remained detained there. He spoke of his dreams for a radically different world. And he began to make plans to see the new video of the talk by RCP Chairman Bob Avakian and to get a copy sent back to Palestine. Sadly, I never got to see Farouk again.

Farouk was precious and loved by the people—and he will be remembered and honored.

(A memorial will be held on November 13. For information, call 201-951-6919 or 212-674-9499, freefarouk.org.)