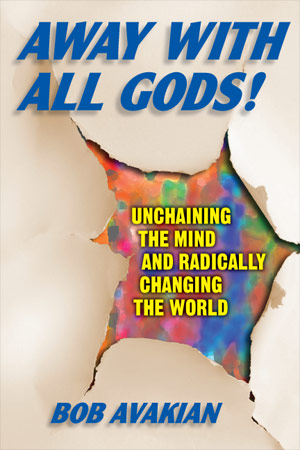

Excerpt from AWAY WITH ALL GODS! Unchaining the Mind and Radically Changing the World by Bob Avakian

The Bible Belt Is the Lynching Belt:

Slavery, White Supremacy and Religion in America

by Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

May 27, 2017 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Editors' Note: The following is an excerpt from the book AWAY WITH ALL GODS! Unchaining the Mind and Radically Changing the World, by Bob Avakian (available from Insight Press). The book was published in 2008.

For a number of years now, I have been thinking about—and pondering the implications of—the fact that what’s called the “Bible Belt” in the U.S. is also the Lynching Belt. Those parts of the country where fundamentalist religion has been historically and most powerfully rooted, and is so even today, are also the places where historically the most brutal oppression has been carried out and has been justified, over and over again, in the name of Christianity. In America, with its whole history of oppression of Black people—beginning with slavery and continuing in various forms down to the present—upholding tradition and traditional morality, and insisting on unthinking obedience to authority, is bound to go hand in hand with white supremacy, as well as male supremacy.

The questions arise in this connection: Is this just an accidental association—between the Bible Belt and the Lynching Belt—or is this something more deeply rooted and causally connected? And, if the latter, what are the historical and material roots of this connection between the Bible Belt and the Lynching Belt, between Christian fundamentalism and white supremacy in the history of the U.S.?

One of the key events and turning points in relation to all this took place in the aftermath of the Civil War, with the reversal and betrayal of Reconstruction in the southern U.S. To briefly review this crucial period: For a decade after the Civil War, from 1867 to 1877, the federal troops that had conquered the South, remained in the South to enforce changes that were being brought about through amendments to the Constitution and government policy in general. And there was, for a very short-lived period of time, not equality but real advances for the masses of former slaves, and even for some poor people among the whites. This included what was then a decisive dimension: the acquiring of land. Not all the land that was promised to the former slaves who fought on the Union side in the Civil War (the famous 40 acres and a mule that you see referred to in Spike Lee movies), but some land was acquired by the former slaves, as well as some poor white farmers. And, although still under the domination of the bourgeoisie and within the structure of bourgeois relations, there were a number of important rights that were extended to the former slaves that obviously had not existed under slavery—including the right to vote. As a result of this, there were also a number of Black elected officials during this very brief period in the southern states.23

But then, the bourgeoisie centered in the North, having consolidated its control of the country, including the South, economically as well as politically, needed to expand further to the west, and it sent the army that had fought the Civil War (and had remained in the South for a decade after the Civil War) to the west, to carry out the final phases of the conquest and genocide against the native peoples, the theft of their land, and the driving of those who were left onto reservations, which were in effect concentration camps.24 Pulling these federal army troops out of the South signaled the end of Reconstruction and returned the masses of Black people in particular to a situation of being viciously exploited and terrorized by old and new plantation owners and the Ku Klux Klan, which was started by former Confederate officers and soldiers seeking revenge for the defeat in the Civil War and a restoration of the “southern way of life.”

Along with this came the development, among white southerners, of a certain strain of Christianity, and in particular Christian fundamentalism, that viewed the southern U.S.—and more specifically the whites in the South—as a people who, like the ancient Israelites, had been favored by their God but then had lost favor with and had been chastised by Him. Their chastisement, in the eyes of these white southerners, was not because of slavery, but rather because they had not been strong enough in defense of their way of life—which in fact was based on slavery. And now, in their view, there was going to be a restoration of this people, as there was in past times when God had returned his favor to the ancient people of Israel.

And what went along with this, not just in the South but in the U.S. as a whole, was that increasingly the history of the Civil War was rewritten, and the role of Black people in the Civil War was basically washed out of historical accounts of this war (this is something that David Brion Davis speaks to in his book, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World). Even the basic reality of what the war was fought over was to a large degree blotted out, obscured, and distorted. Though the Civil War involved a complex of factors and motivations (people on the northern side were not fighting only out of moral conviction, though there were many people motivated to fight on a moral basis against slavery, and many who were inspired, for example, by the rebellion, even though unsuccessful, that was led by John Brown against the slave system shortly before the start of the Civil War), the essence and decisive point of the conflict was—and it became increasingly clear that it was—the question of slavery. On the side of the North, whose victory led to the abolition of slavery, what was essentially involved was the fact that the interests of the rising bourgeoisie (centered in the North) were coming into more profound and acute antagonism with the slave system and the slaveowners in the South. This heightening antagonism between these two modes of production, these two different systems of exploitation—capitalist and slaveowning—was at the root of this conflict; and the reality, which became increasingly clear, was that the bourgeoisie, and its mode of production, could not prevail without finally abolishing slavery. Still, notwithstanding the contradictory nature of the bourgeois side in this conflict (which, among other things, was manifested in the halting and partial way in which Lincoln approached the abolition of slavery), there is no doubt that the central and pivotal issue in the Civil War was slavery.

But, again, especially after the reversal of Reconstruction, there began to be a rewriting of this. “The War Between the States” was how it was increasingly referred to. And then you began to have re-enactments of key engagements in that war which were sanitized versions of what it was all about: people—overwhelmingly white people—would dress up in gray uniforms and blue uniforms (representing the South and the North) and re-enact key battles (this still goes on). This even found expression in the realm of sports. When I was a kid, and for some time after that, there was the annual Blue-Gray football game, an all-star contest pitting college seniors from the South against others from the North. The Civil War became ritualized, and reduced to almost a non-antagonistic conflict within the family, even while there was deeply harbored resentment among the un-reconstructed southern segregationists who looked back longingly to the “glory” of the Confederacy and slavery days. Actually, it was more among the people—that is, the white people—in the North that the sense of antagonism had largely faded.

This rewriting of history—and cultural expressions of this rewriting—were linked with a fundamentalist Christianity which had its roots in the South but was spread—and increasingly these days is being very actively spread—to other parts of the country, not only in rural areas but also within the suburbs and exurbs. And, in what is a terrible and outrageous irony, this same religious fundamentalism is being spread in the inner cities as well, promoted among Black people in particular by patriarchal-minded and reactionary preachers.

In the way that the Civil War has come to be presented as a national tragedy, there is great irony as well: In reality, the Civil War, on a far greater scale than the American War of Independence, had a genuinely liberating content, on the part of the North. Even though this was led by the bourgeoisie and was ultimately contained within the confines of bourgeois relations, the Civil War is the last war on the part of the U.S. capitalist class that can legitimately be considered just, and even glorious. And it’s the only war that they are ashamed of. [Laughter] This is why we repeatedly hear of the terrible tragedy of “brother killing brother.” Well, I don’t believe it was seen that way by the slaves—I don’t think the 200,000 former slaves who, once they were permitted to do so, fought heroically in the Union Army, thought that they were killing their “brothers” when they were fighting the Confederate Army. And I don’t know if a lot of the white troops in the northern army who went to battle singing in praise of John Brown thought they were killing “brothers.” I believe they thought they were carrying on a righteous fight to end a terrible evil.

But, as seen through the eyes of the ruling bourgeoisie today—and in the way it has molded, or sought to mold, public opinion—the Civil War was a terrible national tragedy. And the truth is that it was fought at terrible cost. The 600,000 who died in that war represent the equivalent of something like 6 million people, in relation to today’s U.S. population. But, despite the very real cost, the people who fought it at the time—actually on both sides, but here I’m focusing on the people who were on the liberating side of the war, on the side opposed to slavery—they believed that they were fighting a righteous war, a just war. And that was profoundly true—but it has been rewritten.

In relation not only to the Civil War but to the larger phenomenon of religion and white supremacy in America—and why it is that the Bible Belt is also the Lynching Belt—there is important analysis in Kevin Phillips’ book American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century. In Chapter 4, “Radicalized Religion: As American as Apple Pie,” Phillips makes this observation: “The South...long ago passed New England as the region most caught up in manifest destiny and covenanted relationship with God.” (American Theocracy, p.125)

What Phillips is speaking to is the fact that, going back to the origins of the country, in New England there was a strong current among the settlers of seeing the establishment of their new home in America as expressive of a special relationship with God, and a carrying out of His will. But over the period since then, that has largely receded into the background in New England, while it has become much more powerfully felt and asserted on the part of southerners—that is to say, once again, white southerners (or a large number of them). And those southerners fervently believe that this applies both to the U.S. as a whole but also, more particularly and specially, to the southern U.S. Thus, referring with the term “American exceptionalism” to the notion that America occupies a special destiny and a special place in God’s plan and is marked by a special goodness, Phillips continues: “It [the South] has become the banner region of American exceptionalism, with no small admixture of southern...exceptionalism.” (p. 125) In other words, in the eyes of religious fundamentalists who are rooted in the South and the traditions of the South, since America in general and the South in particular is characterized by this special exceptionalism, when the U.S. ventures into the world and does what might otherwise be regarded as evil, it is on the contrary good, because America has a special goodness inherent in it and what it does is, by definition...good—it is favored in a special way in the eyes of, and has the support of, God.

Phillips reviews how, in the aftermath of the Civil War, although the South was defeated and the slave system was abolished, after the reversal of Reconstruction the South “rose again” in terms of political power and influence within the country as a whole. In connection with all this, Phillips points out, a religious mythology arose, and took root widely among white people in the South, that the (white) South had a special covenant with God and was the object of a special design by God to restore it to its proper place, righting the terrible wrong that had been done through the Civil War. Phillips makes the very relevant and telling comparison between southern whites in the U.S. and white settlers (Afrikaners) in South Africa, as well as Protestants in Northern Ireland and the Zionists who founded and rule the state of Israel. When I read this, it immediately resonated with me, because I had been repeatedly struck by the fact that, in listening to a Northern Irish Protestant, an Afrikaner, or an Israeli spokesman (or Israeli settler in the West Bank), they all seemed, and in certain ways even sounded, remarkably similar, not only in terms of the kinds of arguments they would make, but in their whole posture and attitude. Phillips points out that all these groups, including fundamentalist southern whites, see themselves as people being restored to their rightful, and righteous, relation with God—re-establishing a broken covenant and exercising a special, divinely-established destiny.25

As Phillips sums up: “The reason for spotlighting history’s relative handful of covenanting cultures is the biblical attitudes their people invariably share: religious intensity, insecure history, and willingness to sign up with an Old Testament god of war for protection.” (American Theocracy, p. 128) This insightful observation on Phillips’ part applies to the South of the U.S.—to southern whites in particular—and applies as well to those more broadly in the U.S. who are drawn to a literalist, fundamentalist Christian Fascism. And Phillips goes on to emphasize that the importance of this in today’s world has “less to do with Ulster [Northern Ireland Protestants] and South Africa and more to do with the United States and particularly the South. Israelis and, to an extent, Scripture-reading Americans are on their ways to being the last peoples of the covenant.” (p. 128) Phillips makes the chilling point that this outlook and the corresponding values are gaining currency and force among growing numbers of people all over the U.S.—and once more, in a bitter irony, this includes some among those who are most directly oppressed by white supremacy.

As this worldview has increasingly spread beyond the traditional Bible Belt in the U.S., and as this gains increasing weight within the ruling class of the U.S., it poses the prospect of a move to impose, through force and violence, in the U.S. and on a world scale, all that is called to mind by the slave whip and the lynch rope. And today (employing again a formulation from Phillips) this is embodied as, and comes with, the destructive power of “the preemptive righteousness of a biblical nation become a high-technology, gospel-spreading superpower.” (American Theocracy, p. 103)26

One of the things that David Brion Davis speaks to in Inhuman Bondage (and this is something I also pointed out in Democracy: Can’t We Do Better Than That?) is that, along with arguments by Aristotle justifying slavery, one of the main things cited by the apologists and defenders of slavery in the southern U.S. was the Bible. More specifically, the story of how Noah’s son Ham incurred the wrath of God—so that God cast Ham into Africa and put a curse on the descendants of Ham, beginning with his son, Canaan—was repeatedly invoked to give a religious sanctification to the massive enslavement of people of African origin in the American South.27

For all the reasons that I’ve been speaking to (and which the statements I have cited from Kevin Phillips shine a light on), unavoidably bound up with religious fundamentalism in the U.S., given the whole history of this country, is a definite and pronounced component of white supremacy. And this is objectively true, even though not every individual caught up in this religious fundamentalism is conscious of this fact.

And, again, one of the bitter and acute ironies in all this is the spread of this religious fundamentalism—to a large degree with the battering ram of the forceful reassertion of absolutist patriarchal authority—among those who are most directly the victims of white supremacy. To the degree that this takes hold among them, it will have the effect of binding them more firmly into a whole process which will not only greatly intensify their oppression, but which has genocidal implications, particularly in a situation in which already huge numbers of inner city youth—a large percentage of Black youth and many Latino youth as well—are already in prison or ensnared in the “criminal justice system” in one form or another.

Before turning more directly to these genocidal implications, it is worthwhile looking at another dimension in which, in the history of this country, white supremacy has been mutually reinforcing with the promotion of religion. In the book When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America, in the course of analyzing the way in which the New Deal and the policies effected through the GI Bill, the Federal Housing Authority, the Veterans Administration, and so on, served to actually reinforce and promote white supremacy and a widening of the gap between whites and Blacks in the U.S.,28 Ira Katznelson discusses specifically how this affected colleges and universities. He examines how government funds went in greater proportion to universities from which Black people were, in the early years after World War 2, still almost entirely excluded, and the disparity in government support, financially and otherwise, for Black universities compared to universities that largely, or entirely, excluded Black people. One thing he touches on, as part of this overall analysis, is the historically restricted curriculum of these traditionally Black colleges. With their limited resources and funding—but also partly under the influence of the whole tradition associated with Booker T. Washington—their curriculum was largely limited to, and emphasized, three things: trades, teaching, and theology. (See Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2005—Chapter 5, “White Veterans Only,” especially part III, pp. 129–34.)

In other words, there was a much greater emphasis on religion in the traditionally Black colleges than there was in other universities, from which Blacks were largely excluded for many years continuing after World War 2. Katznelson’s focus here is particularly on the period right after World War 2, but the differences he discusses cast a larger and longer shadow and have broader application and implications and effects, extending down to today. The promotion of theology in the traditionally Black colleges reinforced the role that historically had been played by the Black church, which was a highly and acutely contradictory role.

From the time of slavery, Christianity has been promoted among Black people in the U.S. by the powers-that-be. The various peoples in Africa from which the slaves were taken practiced a number of different religions, and along with forcing them to adopt a new culture and customs—down to the level of requiring them to take on new names (as dramatized, for example, in the televised special series Roots)—the slaveowners generally imposed Christianity in place of the slaves’ traditional religions.29

At the same time, as is not surprising among an oppressed people, beginning in slave times Black people have sought to take parts of this new religion, introduced to them under the yoke of the slavemaster, and use it as a means of fighting back against oppression. So, for example, the Old Testament story of the Israelites enslaved in Egypt and of Moses leading the people out of bondage—the theme of “let my people go,” expressed in gospel songs and in other ways—became a powerful part of the Black religious tradition and culture. But the role of the Black church has always involved a certain kind of dual role, and the role of Black clergy has always been a contradictory one, at times acutely so. It has involved negotiating with the slavemasters (and the white supremacist authorities who have exercised power after slavery was ended) to try to bring about some improvement in the conditions of the people—but always doing so on a basis that would keep things from getting out of hand in a way that would fundamentally threaten the interests of the oppressors; always waging the struggle, or seeking to confine struggle that breaks out, within a form that wouldn’t fundamentally challenge the oppressive relations. Time and again, especially when tension would mount and the anger of the masses would threaten to boil over, the preachers would go to the oppressors and say, in effect: “If you don’t give me something to go back to the people with, I won’t have any way to keep things from exploding.”

Martin Luther King played this role—and explicitly so. In the midst of the massive urban rebellions of the 1960s, King repeatedly took the stand: If you don’t give me something, I’m not going to be able to contain the anger of the masses any more. And when it came down to it, when the anger of the masses did erupt out of the confines that were acceptable to the powers-that-be, King joined in the chorus calling for the government to send in the army to forcibly put down mass urban rebellion. This is the stand King took in the context of the extremely powerful urban rebellion in Detroit, in the summer of 1967; and it must be said that when the army was sent into Detroit, violence did not then stop but was increasingly characterized by violence on the part of the army (together with the police and other agencies of the state) directed against the masses of Black people, many of whom were murdered in cold blood by the army and police. This is a matter of history.

Even if we allow that King did this because of sincere commitment to pacifism, a strategic opposition to violent struggle on the part of the oppressed and a feeling that Black people would only harm their own interests by engaging in violent uprisings, it must be said that this reasoning is fundamentally wrong and is objectively in line with the interests of the oppressors. In fact, King’s role in relation to these rebellions, and overall, was consistent with his expressed view that equality and justice for Black people must, and could only, be achieved within the confines of the capitalist system, and on the terms of this system, when in reality this system has always embodied, in its very foundation, and continually reinforces, inequality and oppression, in the most murderous forms, for the masses of Black people, and only sweeping aside this system through revolution can put an end to this.30

This is the role that this whole stratum of Black preachers has played historically, even while they have been portrayed as the leaders of the struggle. In truth, their role has been much more contradictory—and often much more acutely contradictory—than that.31

In relation to all this, two things stand out very clearly today: One, it is necessary to be very clear that this ideology—the theology of Christianity, and of religion in general, and the overall worldview that it expresses—cannot lead the way to real and complete liberation, and on its own it will always end up seeking to confine things within the limits set by the existing system. To put it in basic terms, to the degree that they are willing to stand with the oppressed in the fight against oppression and injustice, religious clergy and others with this outlook can and must be united with, but the outlook and the political orientation that they represent cannot lead the struggle, or it will not go where it needs to go in order to bring about emancipation from oppression and exploitation. And secondly, there is at this time a whole stratum or section of Black preachers which is openly going along with and promoting the Christian fascist program, to a large degree on the basis of aggressively asserting patriarchy in particular. And that can only lead to disaster: it cannot be united with and has to be very vigorously exposed, called out for what it is, and relentlessly struggled against.32

23. The U.S. is a weird country—the oppressive relations in this country have taken some peculiar forms. I remember doing some research into this a number of years ago, and discovering that if you were determined to be 1/16th African, you were counted as Black in some of these calculations in the South. And so, on the basis of this definition, there was one person (I still remember his name: P.B.S. Pinchback) who became Lieutenant Governor in a southern state during the period of Reconstruction; he held the highest political office in the South of any person of African origin (defined in this way), until quite recently. But even with certain peculiarities to this, it is a reflection of changes that were brought about as a result of the Civil War and the very brief period of Reconstruction. [back]

24. These federal troops were also used against strikes carried out by what was then an overwhelmingly white labor movement. [back]

25. Here there is a notable irony, with regard to the Zionist rulers of Israel in particular: while many of them are actually secular, they nonetheless base their claim to the land of Palestine on religious-scriptural grounds. As a joke, which used to circulate in Israel itself, puts it: “Most Israelis don’t believe in God—but they do know He promised them the state of Israel!” [back]

26. Along with the important analysis and insights in Kevin Phillips’ book, American Theocracy, as well as in Inhuman Bondage by David Brion Davis, observations that are very relevant to this question are found in The Baptizing of America, by Rabbi James Rudin, as well as in a talk, in May, 2005, by African-American theologian Dr. Hubert Locke, “Reflections on the Pacific School of Religion’s Response to the Religious Right.” [back]

27. In more recent times, once again we have seen arguments seeking to justify and reinforce white supremacy being treated very respectably in the bourgeois media and other “mainstream” institutions. This was the case with The Bell Curve, for example—a book that was published and was promoted very aggressively in the 1990s. In setting out to justify oppressive relations in general—and, more specifically, white supremacy—this book did not rely so much on religious scripture for justification, but based its arguments on pseudo-scientific rationalization for what it alleged were the innate inferiority and superiority of various groups. It explicitly argued that there is a genetically-based inferiority of people of African origin, particularly with regard to intellectual capacities. This was raised to oppose programs such as affirmative action, but also more generally to justify unequal and oppressive relations and to reinforce the ideology of white chauvinism (racism) that goes along with the way in which white supremacy is built into the whole history and foundation, and the dominant institutions and structures, of U.S. society. However, increasingly in these times in the U.S. we see religious fundamentalism being brought forward as a unifying ideological basis for the most openly reactionary viewpoints and political programs, including white supremacy as well as male supremacy. [back]

28. An analysis of the role and effect of the New Deal and related programs in reinforcing white supremacy and inequality is also found in WorkingToward Whiteness, How America’s Immigrants Became White, The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs, by David R. Roediger, Basic Books, 2005. [back]

29. Despite some definite limitations, some useful background in this regard is found in Religions Of Africa: A Pilgrimage Into Traditional Religions, by Noel Q. King, Harper & Row Publishers, 1970; and The Religions Of The Oppressed: A Study of Modern Messianic Cults, by Vittorio Lanternari [Translated from the Italian by Lisa Sergio], Alfred A. Knopf, 1963. [back]

30. See Cold Truth, Liberating Truth: How This System Has Always Oppressed Black People, and How All Oppression Can Finally Be Ended, available at revcom.us/coldtruth, where the following statement by Martin Luther King is cited, which makes very clear his outlook and orientation and the unity between the objective he put forward of pursuing (the illusion of) achieving equality within this system and his insistence on what the character of the struggle must be:

“The American racial revolution has been a revolution to ‘get in’ rather than to overthrow. We want a share in the American economy, the housing market, the educational system and the social opportunities. This goal itself indicates that a social change in America must be nonviolent.” (Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go From Here, p. 130, cited in Cold Truth, Liberating Truth, Part 7, “Any Other Way Is Confusion and Illusion”) [back]

31. You can see these contradictions portrayed, for example, in a movie that came out in the ’60s, Nothing But a Man. This movie was not widely distributed, but it is a very interesting and overall a very positive movie, even with its limitations, which are reflected to some degree in the title. It is the story of a Black railroad worker in the South who, because his job provides more mobility for him, and he has some experience with unions, doesn’t want to put up with all the overt racist crap that Black people were subjected to in the South at that time. At one point he meets, falls in love with and marries the daughter of a preacher, and he comes into very sharp conflict with the preacher because of his whole attitude of refusing to put up with all this—and his contempt for Black people, including this preacher, who do put up with or compromise with the whole racist set-up. The movie very well portrays the kind of conciliating role of the preacher—negotiating to get a few concessions and at the same time struggling to keep the people in line, so that they don’t anger the Man and upset the whole arrangement. This movie captures a lot of the acutely contradictory role, historically, of this stratum of Black preachers and the theology they have purveyed. Contrary to the mythology that’s promoted by the ruling class, as well as by many of these preachers—that they’ve always been out in front, leading the struggle—the reality is once again much more contradictory: While some Black clergy have played a positive role and made real contributions to the struggle, there has also been a significant aspect in which many of them have sought to contain the struggle within limits that are more acceptable to the ruling class—particularly in circumstances when the struggle has powerfully strained against, and at times broken through, the limits they seek to impose on it in order to maintain this arrangement with the ruling class whereby the preachers can get certain concessions in return for keeping the masses in line and preventing them from getting all out of bounds. [back]

32. As an aside here, dealing with a secondary but not insignificant part of the picture, it is worth thinking about why is there an unusually large representation of white people from the South not only in the U.S. military overall but more specifically in the officer corps. Now, as for the “grunts,” that can be explained to a significant degree by the fact that there actually are a significant number of white people in the South whose options are limited. But there is also the whole macho and militaristic ethos that has historically gone along with the influence of religious fundamentalism and generally conservative culture and values—it is not accidental, or incidental, for example, that “patriot” and “patriarchy” are words with the same root. And, specifically with regard to the large numbers of white southerners in the officer corps of the U.S. armed forces, along with this macho and militaristic ethos, there is the whole history of the southern aristocracy, beginning with the slave system but then continuing after literal slavery was abolished (and replaced with a system of sharecropping and plantation exploitation, in what was essentially a feudal form, for a period of about 100 years after the Civil War). This whole aristocratic tradition in the South was consciously carried over and copied from Europe, and if you look at a country like England, with its aristocracy, there is the tradition where one son inherits the family’s property, another joins the clergy, and yet another son goes into the military. And there are not only ideological but also practical factors that play into that. With a system where wealth is based on land ownership, to the degree that you are not able to more intensively exploit people on the land, then there is a limit to how much wealth you can accumulate; and if you keep dividing up the land, you will end up in a situation where the family wealth will actually begin to be used up. But, if you send one son into the clergy and another into the military, there will not be so many to divide the land among (and less basis for rivalry and antagonism among the sons). To a significant degree, this was historically part of the culture of the southern U.S.—that is, of the rich white land-owning aristocratic strata in the South—and this is quite possibly one of the factors that has contributed to there being so many white southerners not only in the U.S. military overall but specifically in its officer corps. And, in turn, given the historical particularities of the South, as spoken to above, this presence of a large number of white southerners is a factor contributing to a more favorable environment for the spread of religious fundamentalism—Christian Fascism—within the U.S. military, including its top ranks. [back]