Case #28: U.S. Foments Bloody Civil War in Angola,

1975-2002

| Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has "to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this." (See "3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.")

In that light, and in that spirit, "American Crime" is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIME

For 27 years, from 1975 to 2002, the U.S. fueled a reactionary and immensely bloody civil war in Angola, a country in Southern Africa. The war led to the deaths of some half a million Angolans and millions were driven from their homes.

In 1975, after years of struggle by the Angolan people, Portugal—which had dominated that area of Africa for centuries—was forced to grant independence to Angola and its other African colonies. The U.S. had supported Portugal in its efforts to crush the opposition and sustain its colonial rule of Angola, including by providing the colonizers with napalm.

At the same time, the U.S. kept its options open by supplying aid to one of the three groups in the fight for Angolan independence, the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola). The U.S. backing was not about genuine support for an anti-colonial struggle for independence; it was aimed as a counterweight to the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola), which received political and military backing from the Soviet Union. At the time, the Soviet Union was an imperialist power contending globally with the U.S. There was a third Angolan independence group—UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), headed by Jonas Savimbi, a corrupt, vicious warlord who was developing ties with South Africa’s apartheid rulers.

With the imminent end of Portuguese rule in 1975, the MPLA emerged as the largest and best organized of the anti-colonial groups and was set to take power. Scrambling to maintain its own foothold in Angola and counter the Soviets, the U.S. discouraged the FNLA and UNITA from coming to terms with the MPLA. And the U.S. sent funds, arms, and CIA operatives to solidify the FNLA and UNITA as pro-U.S., anti-MPLA forces.

The U.S. became deeply involved in the Angolan civil war, while the White House and the CIA publicly denied they had any hand in the conflict. The CIA recruited U.S. and British mercenaries to operate in Angola against the MPLA. They waged disinformation campaigns on behalf of the groups they supported. They encouraged apartheid South Africa and the brutal regime of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire to back the FNLA and UNITA.1 U.S. personnel flew between Zaire and Angola to carry out reconnaissance and supply missions to help the anti-MPLA forces.

In 1976, the U.S. Congress passed the Arms Export Control Act (the Clark Amendment), which prohibited the U.S. government from giving direct or indirect aid to groups engaged in military or paramilitary operations in Angola. The CIA ignored the Clark Amendment and used covert ways to channel arms and aid to the anti-MPLA forces.2

The Angolan war took a major leap after the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan as U.S. president. Reagan stepped up support for UNITA and Savimbi. A lot of this U.S. aid was through the South African apartheid regime, which had intervened directly in Angola against the MPLA government. According to William Blum, “In 1984 a confidential memorandum smuggled out of Zaire revealed that the United States and South Africa had met in November 1983 to discuss destabilization of the Angolan government. Plans were drawn up to supply more military aid to UNITA (the FNLA was now defunct) and discussions were held on ways to implement a wide range of tactics: unify the anti-government movements, stir up popular feeling against the government, sabotage factories and transportation systems, seize strategic points, disrupt joint Angola-Soviet projects, undermine relations between the government and the Soviet Union and Cuba, bring pressure to bear on Cuba to withdraw its troops, sow divisions in the ranks of the MPLA leadership, infiltrate agents into the Angolan army, and apply pressure to stem the flow of foreign investments into Angola.”3

The U.S. also arranged for its allies, especially Israel, to back the South African apartheid regime by training its military, providing weapons technology, and training its “intelligence” agencies in torture. An important aspect of this was to help South Africa wage war in Angola. In 1982, the U.S. urged the International Monetary Fund to grant South Africa $1.1 billion in credit, an amount that happened to be equal to the increase in South African military expenditure from 1980 to 1982.

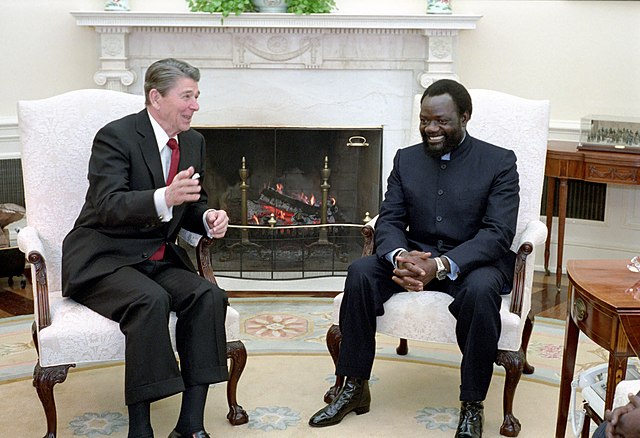

In 1985, Congress repealed the Clark Amendment, and this quickly led to a jump in open U.S. intervention in Angola. In 1986, Reagan invited UNITA’s Savimbi to the White House, where Reagan’s top official for Africa praised him as “one of the most talented and charismatic of leaders in modern African history.” After a meeting with Savimbi, Reagan said that he could envision a UNITA “victory that electrifies the world” and called him a “freedom fighter.” The Reagan administration promised Savimbi U.S. backing for an escalation in the war against the MPLA. In January 1987, the U.S. announced that it was providing the anti-MPLA forces in Angola with Stinger missiles and other anti-aircraft weaponry.

In 1988, South Africa sent a heavily armed invasion force to southern Angola to help UNITA launch an offensive with the goal of seizing the capital city, Luanda. In the strategic area of Cuito Cuanavale, the South African military clashed with Cuban forces who were armed with advanced weapons and planes supplied by the Soviet Union.

The South African/UNITA forces suffered defeat in this largest battle in Africa since World War 2, but the U.S. continued to back UNITA after this setback, and the Angolan conflict continued for another 14 bloody years.

Savimbi’s UNITA lost much of its credibility as a “liberation” force because of its open alliance with apartheid South Africa and Zaire’s Mobutu regime. But UNITA controlled the diamond-producing regions of Angola, and a huge diamond smuggling network (worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year) gave Savimbi the financial support for continuing the war. The “blood diamonds” produced in the Angolan mines by workers who toiled in terrible, even deadly, conditions were marketed by South African companies.

The U.S. rulers only dialed back their support for their forces in the Angolan civil war in 1993, several years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The MPLA stopped claiming to be “Marxist-Leninist,” a self-identification that it had adopted when they were backed by the Soviet Union, which itself was “communist” in name but capitalist-imperialist in reality. The MPLA adopted social democracy and called for multiparty elections, aligning itself with the U.S. and other imperialist countries. In the 1992 election, Savimbi and UNITA was outvoted by José dos Santos of the MPLA. Savimbi refused to recognize the legitimacy of the election and reignited the civil war with horrendous consequences in death and destruction, which continued until Savimbi’s death in 2002.4

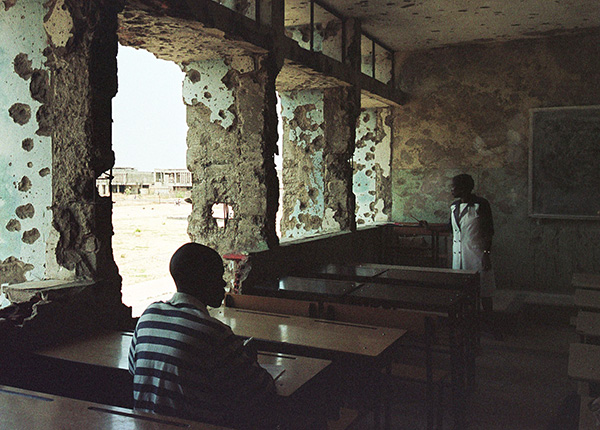

By that time, about 500,000 Angolans had been killed and millions internally displaced. The widespread use of land mines resulted in one of the highest amputee rates in the world. The aftermath of the civil war left Angola with much of its public institutions, economic enterprises, religious institutions, infrastructure, and medical and other basic life support systems in ruins.

Refugees returning to Angola in 2003 found a country where, according to the United Nations, “80 percent of people have no access to basic medical care. More than two-thirds have no running water. A whole generation of children has never opened a schoolbook. Life expectancy is less than 40 years. Three in ten children will die before reaching their fifth birthday.”5

THE CRIMINALS

U.S. President Gerald Ford and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: Ford was president and Kissinger the secretary of state in 1975 when the U.S. intervened in Angola to oppose forces allied with the Soviet Union. Author William Blum noted that Kissinger “was wholly obsessed with countering Soviet moves anywhere on the planet—significant or trivial, real or imagined, fait accompli or anticipated.” This was because the U.S., which had come out as the top imperialist power at the end of World War 2, was now facing a global challenge from the Soviet Union, which had become an imperialist power since socialism was defeated there in the mid-1950s.

CIA: In the mid-1970s, in anticipation of Angola’s independence from Portugal, the CIA assigned John Stockwell (a case officer during the U.S. war in Vietnam and then in Africa) to build up pro-U.S. FNLA and UNITA organizations. Stockwell later quit the CIA in disgust and wrote about his work with the CIA in Angola. In In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story, he wrote, “During September and October, [1975] the CIA with remarkable support from diverse U.S. government and military offices around the world, mounted the controversial, economy size war with single minded ruthlessness.”

U.S. President Ronald Reagan: Reagan ushered in a more aggressive, militarist strategy in U.S. imperialism’s global contention and conflict with the Soviet Union, the so-called “Reagan Doctrine.” In Angola, this fueled the continuing civil war and led directly to untold suffering for the Angolan people.

Heritage Foundation: This right-wing “think tank” lobbied on behalf of Reagan’s policies in Angola. During his visit to the U.S., Jonas Savimbi of UNITA praised the Heritage Foundation for its critical role in advocating the repeal of the Clark Amendment: “When we come to the Heritage Foundation, it is like coming back home. We know that our success here in Washington in repealing the Clark Amendment and obtaining American assistance for our cause is very much associated with your efforts.”

South Africa’s Apartheid Regime: From the mid-1970s until the early 1990s, the apartheid regime repeatedly intervened in Angola, including by sending troops and armored columns intent on destroying the MPLA government in the interest of crushing African liberation forces and coming to the aid of U.S. imperialism while advancing its own regional ambitions.

Israel: Israel acted as a proxy arms supplier to pro-U.S. forces in the early years of the Angolan civil war. This was especially helpful for the CIA and U.S. administrations after the passage of the Clark Amendment in skirting the formal restrictions on aid to the Angolan forces.

THE ALIBI

Whether acting covertly in the immediate period after the withdrawal of the Portuguese from Angola in 1975 or more openly under Reagan after 1980, the U.S. claimed it represented “freedom” and “democracy” in conflict with Soviet “communism” and portrayed all forces that opposed them as dupes of the “evil Soviet empire.” In 1975, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, Patrick Moynihan, declared that if the U.S. did not step in, “the Communists would take over Angola and will thereby considerably control the oil shipping lanes from the Persian Gulf to Europe. They will be next to Brazil. They will have a large chunk of Africa, and the world will be different in the aftermath if they succeed.”

THE REAL MOTIVE

Anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles swept the world in the 1960s and 1970s, dealing blows to the U.S. and other western imperialist powers. Meanwhile, after the defeat of socialism and restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union in the mid-1950s, the Soviets had emerged as an imperialist power and the head of its own bloc, challenging U.S. military, economic, and geostrategic domination in different parts of the world.

Angola became one of the battlegrounds in this global imperialist contention. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who was instrumental in the CIA intervention in the Angolan civil war, wrote, “Angola represents the first time that the Soviets have moved militarily at long distance to impose a regime of their choice.” The U.S. imperialists already had a long history of “imposing a regime of their choice”—through coups and other means—around the world in pursuit of their interests, but they were now facing an enemy imperialist power that was moving to establish its own foothold in Southern Africa. The U.S. rulers saw that as a dangerous challenge, and they set out to beat back their rivals—at an immense cost in human lives in the oppressed nation of Angola.

Sources

Aaronovich, David. “The Terrible Legacy of the Reagan Years,” Guardian, June 7, 2004.

Blum, William. Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Intervention Since World War II. Zed Books, 2014.

Stockwell, John. In Search of Enemies, A CIA Story. Norton, 1978.

The Angolan Civil War (1975-2002). BlackPast.org.

“American Crime Case #73: The CIA-Directed Murder of Patrice Lumumba,” November 7, 2016.

Footnotes

1. In 1960, Mobutu had collaborated with the CIA in the coup against Patrice Lumumba, the nationalist leader of Congo (and the subsequent assassination of Lumumba). For his role in the coup and assassination and in bringing a swift end to any notions of real independence for the Congo (which was renamed Zaire under Mobutu's rule), the U.S. backed Mobutu’s rise to power and 32-year-long rule. With U.S. support, he ruled the country with an iron fist, crushing opposition while amassing a huge personal fortune. All the while, the U.S. had free rein to plunder the country’s rich resources. For more, see “American Crime Case #73: The CIA-Directed Murder of Patrice Lumumba.” [back]

2. The Soviet Union countered U.S. intervention with escalations of its own. When South Africa openly intervened in Angola in 1976, the Soviet Union made use of the widespread hatred of the apartheid regime to bolster its position in Angola. The Soviets underwrote the deployment of tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers armed with the latest Soviet military weapons to support the MPLA. [back]

3. Killing Hope, Blum. [back]

4. It is beyond the scope of this article to get into what happened after the end of the civil war, including the fact that the clique ruling Angola today, which is marked by vast inequalities, came directly out of the MPLA. We encourage readers to read the section “The Decisive Role of Leadership” (pages 283-295) in Part IV of Bob Avakian’s THE NEW COMMUNISM, in which he discusses how and why those like the MPLA went from leading just struggles to becoming new oppressive ruling forces. [back]

5. “Angolans Come Home to ‘Negative Peace,’” New York Times, July 30, 2003. [back]

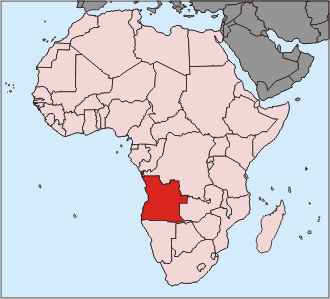

Angola

U.S. President Reagan in a White House meeting with Jonas Savimbi of UNITA, which received American backing in the Angolan civil war, including through the apartheid regime in South Africa. (Photo: Public Domain)

The widespread use of land mines throughout the war resulted in one of the highest amputee rates in the world. (Photo: AP)

The aftermath of the war left Angola with much of its infrastructure and other basic life support systems in ruins. Here, a school destroyed in the war. (Photo: AP)

In the aftermath of more than 25 years of civil war, three in ten children did not survive to their fifth birthday. Above, malnourished Angolan children. (Photo: AP)

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: