Case #26: The 1946 White-Mob Lynching of Two Black Couples at Moore’s Ford, Georgia

| Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIME

In the summer of 1946, a white lynch mob near Moore’s Ford Bridge in Monroe, Georgia (a small rural town about 50 miles east of Atlanta), brutally murdered four Black sharecroppers. Despite abundant evidence, eyewitness accounts and two investigations by the FBI (60 years apart), there has never been a single indictment.

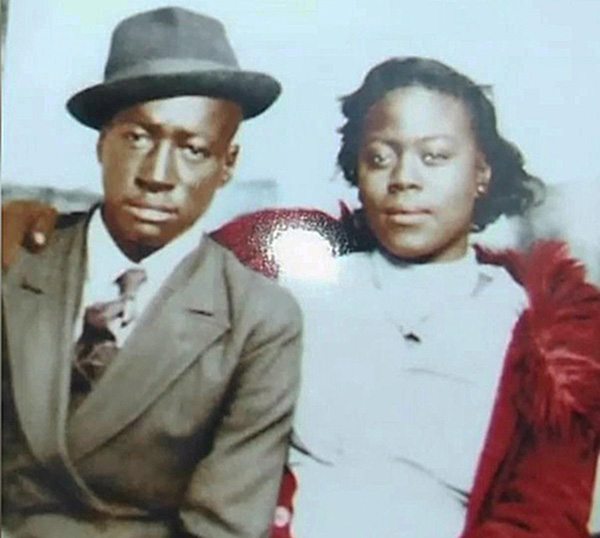

Roger and Dorothy Malcom

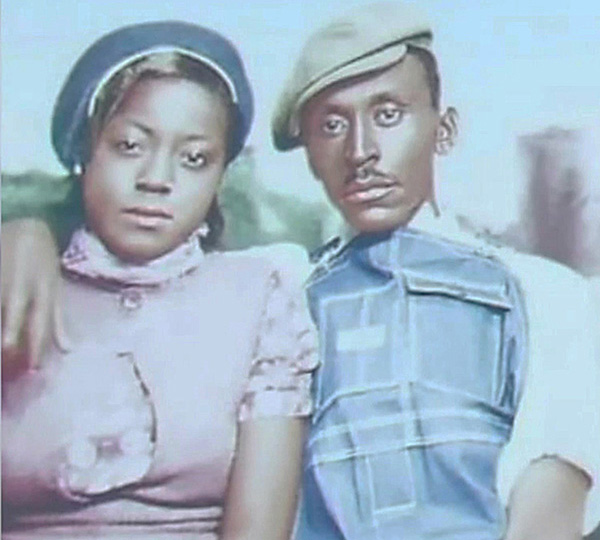

Mae Murray and George Dorsey

The events that would eventually lead to the lynching began on July 11, 1946, when a fight occurred between a Black sharecropper and a white farmer. The sharecropper, Roger Malcom, believed his wife, Dorothy, was having an affair with a white farmer named Barnette Hester. Dorothy and Roger were yelling at each other outside Hester’s home. When Hester tried to intervene, Roger stabbed him with what may have been an ice pick. Hester was seriously injured, and few thought he would survive, but he did. In fact, local newspapers reported on the morning of the day the lynching took place that Hester, for the first time, sat up in his hospital bed.

Roger Malcom knew stabbing a white man was tantamount to suicide; violence and execution pervaded the lives of Southern Blacks. White lynch mobs regularly killed Blacks for false accusations and often for no reason at all. Malcom hoped that jail might provide him some protection from white vigilantes. Even the sheriff believed a mob would come for Malcom, as they did for most Black men accused of harming a white person.

Dorothy Malcom's mother, Moena Dorsey Williams, begged a white farmer named J. Loy Harrison for help to get Roger out of jail. Roger, along with Dorothy's brother, George Dorsey, worked for Harrison. Harrison was known to be a brutal employer, but Moena was desperate to get her daughter’s husband out of jail. Initially, Harrison refused, referencing the repercussions he would face from local whites. Several days later, Harrison surprised everyone when he offered to post Roger Malcom’s bail in exchange for work on his farm.

On July 25, Harrison arrived at the Dorsey home. He invited Dorothy Malcom and her brother, George Dorsey, along with his wife, Mae Murray Dorsey, to accompany him on the ride to town. They happily took the opportunity to leave the farm and go into town. Once they arrived, Harrison told his passengers to go shopping while he ran errands and arranged for Roger Malcom’s release. They agreed to return to the courthouse at 5:00 pm where they’d meet Roger and return home. Harrison went to talk to the sheriff... alone.

After talking with the sheriff for a few minutes, Harrison paid $600 for Roger Malcolm’s release. Everyone got in the car and Harrison drove the longest route toward home. After a few minutes, they exited the highway and turned onto a winding dirt road. Harrison’s car began to approach Moore’s Ford around 5:30 pm, only an hour after Roger’s release. Several yards from the bridge, Harrison stopped. Two dozen white men blocked the road. They were trapped.

The men peered into the car. Some of them held guns. Harrison later told the police: “A big man who was dressed mighty proud in a double-breasted brown suit was giving the orders. He pointed to Roger Malcom and said, ‘We want that nigger.’ Then he pointed to George Dorsey, my nigger, and said, ‘We want you, too, Charlie.’”

The mob ripped the two men out of the car, roped them together and dragged them toward the undergrowth of the river. One woman in the car started calling out the attackers by name. Without hesitation the mob descended on the two women, ripped them from the back seat and tied them to a tree next to their husbands. Bound and unable to run, their fate was sealed.

The bodies of George, Mae, Roger, and Dorothy were found disfigured beyond recognition. Bullets fired at point-blank range filled the victims’ faces and arms. George Dorsey’s body lay face down on the ground with bullet and shotgun wounds covering his arms, head, and back. The lynch mob singled out Roger Malcom for the worst punishment—a shotgun blast exploded his face and the noose of a 10-foot-long rope encircled his neck. Another rope held his hands tied to George’s. Dorothy Malcom’s disfigured face pointed toward her husband, Roger. Dorothy’s body touched Mae Murray Dorsey’s. Mae was closest to the road—her body was in a crouched position, a large-caliber bullet had pierced the back of her skull.

After hearing about the lynching at Moore’s Ford, hundreds of whites visited the scene looking for souvenirs, taking bullets and bone fragments. They even pulled up the tree that held the victims.

Four months after the murders, a grand jury convened, ostensibly to identify the killers and bring them to justice. There were 21 white and only two Black jurors. Hundreds of witnesses took the stand. J. Loy Harrison was one of the main suspects, but he claimed he was innocent.

Fearing reprisal, Black residents were reluctant to testify before the grand jury, but at least one brave Black man did. Lamar Howard claimed he saw Harrison at the local icehouse where he was working on July 25, an hour before the murder, deep in conversation with James Verner, a violent white supremacist known to fire shots at Black people. (Both Harrison and Verner admitted to prior membership in the Ku Klux Klan.) Howard also testified he saw Harrison dispose of two pistols behind the icehouse, shortly after the murder. Harrison denied this, but later admitted that he was at the icehouse that day. (Two weeks after Howard gave his testimony, James Verner and his brother Tom showed up at the icehouse where they beat Howard with a pistol while demanding to know what he told the grand jury.)

Harrison’s story had other holes in it. Monroe is a small town, yet Harrison claimed he was unable to recognize a single one of the two dozen men who surrounded his car, nor recall the name of the woman, either Dorothy or Mae, who yelled out when identifying the attackers. Despite these facts, glaring contradictions in testimony by the 20-some suspects, and numerous threats against witnesses, after 16 days the grand jury was “unable to establish the identity of any persons guilty of violating the civil rights statute of the United States.” One man was charged with perjury, but the charge was eventually dropped. The records of this grand jury disappeared but were found in 2017 in the National Archives, and researchers, family members, and activists have filed suit to have them released to the public. The Justice Department objected, arguing that the records don’t meet the requirements for disclosure, and the case is now before the U.S. Court of Appeals.

The gruesome murder shocked the conscience of people around the globe. News of the Georgia lynching ran alongside articles about the trials of Nazis for atrocities in Europe during World War 2, with headlines announcing prosecutors’ demand for death sentences for those guilty of “the doctrine of hatred” that permitted murder “conducted like some mass production industry.” Many wondered how the U.S. could denounce the massacres in Europe while ignoring the murder of Blacks domestically.

More than 70 years have passed since the Moore’s Ford lynching and it still resonates today. The community and families of the victims still hope for answers, but with each passing year, their hopes fade. Moore’s Ford, along with thousands of other lynchings in the South, remain unresolved and the killers unaccountable.

THE CRIMINALS

J. Loy Harrison portrayed himself as a helpless victim who, despite his objections, couldn’t stop the mob from murdering the four young Black people in his car. However, the evidence points to Harrison and the sheriff having concocted the lynching plan in the hours before it took place. The sheriff had told Harrison not to bother stopping at the courthouse and to go directly to the jail. Now Roger Malcom could be taken without raising any eyebrows—Walton County never allowed a Black man to be bonded when a white man’s life was in danger without prior approval from “interested people.”

Speaking to investigators, several Black farmhands reported Harrison threatening them and warning them not to speak with agents. One worker reported Harrison warning him and other Black farmhands, “He said if any of us did tell anything, folks would find us scattered about dead.” Harrison also told them he had an informant who would report to him anything they said to agents.

The Police. Local law enforcement conspired with J. Loy Harrison and aided in the murder. Harrison and the sheriff’s deputies coordinated the time Harrison would bail Roger Malcom out of jail, and the route and location of the crime. How were two dozen men able to prepare their weapons and assemble at the bridge in a matter of minutes? Several witnesses said they saw a law enforcement vehicle blocking the road and at least one officer and Harrison taking part in the killing. The sheriff and deputies admitted to cutting segments from the rope tied around Roger Malcom’s neck to keep as souvenirs.

The KKK. In 2008, investigators discovered Ku Klux Klan membership rosters that provided circumstantial evidence of their involvement in the murders. The rosters date back to the 1930s and 1940s and include the names of four men who were suspects in the 1946 investigation. The roster also contained a fifth man listed as an “Exalted Cyclops” of the local Klan chapter in 1939. This Klansman owned the white funeral home that recovered the victims’ bodies before it transferred them to a Black-owned funeral home.

Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge, a Southern Democrat, served several terms as governor before losing the position to a more progressive Democrat. In 1946, Talmadge sought nomination for governor in the Georgia Democratic primary—recently forced by a federal court to allow Black voters. Talmadge centered his entire campaign around white supremacy and maintaining segregation. His campaign ignited white outrage at Blacks who refused to “stay in their place.” In the weeks leading up to the Moore’s Ford lynching, Talmadge led a boisterous crowd in Walton County where he warned Negroes “to stay home and not attempt to vote.” The lynching at Moore’s Ford took place three days before the primary when racial tension was boiling over. Talmadge eventually regained the governorship. White people who sought to maintain Jim Crow segregation celebrated his victory. J. Loy Harrison was a steadfast supporter of Talmadge, even naming one of his sons after him.

The FBI. When the FBI had leads, they failed to pursue them. Even when evidence indicated that the local sheriff had known of the threats against Roger Malcom’s life before the lynching and did nothing to protect him, investigators didn’t even pursue a case.

To make matters worse, whites in Monroe did everything they could to stonewall the investigation; they closed ranks, purposefully misleading investigators, refusing to cooperate and intimidating Black residents who dared speak.

Racial terror and the lynching of Black people were pervasive in the South, but it was rarely investigated. The FBI was far more interested in weakening and suppressing Black people’s growing demand for civil rights than it ever was in prosecuting lynchings. A few years after the Moore’s Ford lynching, when 14-year-old Emmett Till was brutally lynched in Mississippi, FBI head J. Edgar Hoover called it an “alleged murder” and spent more energy investigating communists protesting the lynching than the lynching itself.

U.S. Congress. Civil rights organizations like the NAACP spent years fighting for anti-lynching laws. Despite public outrage following the Moore's Ford lynching, Congress did not enact an anti-lynching bill until 2018. Some 200 anti-lynching bills introduced in Congress between 1877 and 1950 were blocked, particularly by the Southern Democrats (Dixiecrats).

THE ALIBI

A white farmer, J. Loy Harrison, reported to a local sheriff that a mob of 24 unknown white men blocked the road just before Moore’s Ford Bridge and forced his car to a stop. The men attacked the four Black passengers riding in his car. The mob viciously beat and then murdered the two Black men and two Black women. Harrison claimed he did not take part in the killing and recognized none of the attackers.

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE

The heinous lynching at Moore’s Ford provides a glimpse of the barbarity faced by Black people in the South. Even after literal slavery was ended through the Civil War, the horrors of oppression continued for Black people in new forms—including segregation and being chained to the land as sharecroppers—and lynching and its effects were a certain concentration of what the masses of African-Americans faced. For decades under the overt segregation known as Jim Crow in the South, every Black person there faced the threat that at any time they could be brutally murdered for anything they did that might “offend” some white people—or for nothing at all except the color of their skin—and nothing would happen to their killers. This was a key way that the system of white supremacy and the subjugation of Black people were enforced and kept in place.

For Black people, Jim Crow was a looming death sentence. The only evidence white people needed to justify killing a Black person was dark skin and an accusation. Lynching served a reminder to all Black people that they could be next.

A report by the Equal Justice Initiative, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” documents over 4,000 mob killings of Black people between 1877 and 1950 in just 12 Southern states.

Lynchings were often announced days before being carried out. Spectators gathered in a picnic-like atmosphere. White men, women and children cheered as Black bodies dangled from trees, and photographers lined up hoping to get the best photos, which would then be sold as postcards.

After World War 2, major economic transformations were taking place in the South. Many Black people were moving (or being forced) off the land into urban areas, and the political tides were shifting as more and more Black people stood up to injustice. Whites feared the political gains being made by Black people and struggled to repress any move to challenge their dominance. Black veterans like George Dorsey were particularly threatening to Jim Crow and white claims of racial superiority. Thousands of Black veterans were assaulted, threatened, abused and lynched. The number of lynchings rose sharply after the war, with 12 Black people lynched in 1945 alone.

In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that white primaries were unconstitutional, which allowed some Black people to vote in the Democratic Party primaries. The massacre at Moore’s Ford took place two years later.

Sources

Anthony Pitch, The Last Lynching: How a Gruesome Mass Murder Rocked a Small Georgia Town (Skyhorse, 2016).

“Answers to last mass lynching in U.S. die when investigators close case after 72 years,” Southern Poverty Law Center, February 7, 2018.

“Probes of Moore’s Ford lynching end with no charges, AJC learns,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 28, 2017.

“Moore’s Ford lynching: years-long probe yields suspects—but no justice,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 29, 2017.

“FBI questions elderly Georgia man in connection with unsolved 1946 lynching at Moore’s Ford Bridge,” New York Daily News, February 17, 2015.

“A Last Hope for Truth in a Mass Lynching,” New York Times, October 7, 2018.

“Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans,” Equal Justice Initiative

Clips from Revolution: Why It's Necessary, Why It's Possible, What It's All About, a film of a talk by Bob Avakian

“They're selling postcards of the hanging.”

“Emmett Till and Jim Crow: Black people lived under a death sentence.”

Watch the entire film online at revolutiontalk.net.

Clip from BA Speaks: REVOLUTION – Nothing Less!

“How Long?! How Many More Times Do the Tears Have to Flow?”

Watch the entire film online at revolutiontalk.net.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: