Case #21: Chad, 1981‒1990: U.S. Backs Ruthless Torturer, Mass Murderer Hissène Habré—“Africa’s Pinochet”

| revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIME

In March 1981, the CIA under newly elected President Ronald Reagan began providing covert backing and military assistance to Hissène Habré, one of the most ruthless warlords fighting to take power in Chad. That U.S. support would continue for eight more years, as Habré seized power, and ruled so ruthlessly he became known as “Africa’s Pinochet,” after Chile’s U.S.-backed butcher, Gen. Augusto Pinochet.1

The Republic of Chad is a small landlocked country in Central Africa, bordered by Libya, Niger, Nigeria, Central African Republic, Sudan, and Cameroon. It was part of French Equatorial Africa until gaining formal independence in 1960. For most of the 20 years that followed it was racked by civil war and several invasions by Libya, often in support of various factions in Chad. Libya was headed by Muammar Qaddafi and had political and military ties with the Soviet Union, which was in a Cold War conflict with the U.S. during the 1970s and 1980s.

The CIA knew of Habré’s opposition to Qaddafi and his allies in Chad, and they also knew of his warlord atrocities, which had also been reported by the New York Times and Washington Post. This included the discovery of several hundred skeletons of people murdered by his henchmen and buried in the back yard of his home. Nevertheless, in early 1981, Reagan signed a secret presidential finding that authorized covert operations to bring Hissène Habré to power and the CIA, along with France, began covertly supplying Habré with millions of dollars in weapons and other assistance.

In June of 1982 Habré overthrew Goukouni Oueddei’s Libya-backed government, established a provisional government, and declared Chad’s “Third Republic.” Oueddei’s forces continued to battle Habré’s rule from northern Chad with Libyan and Soviet support.

Habré’s regime responded with systematic violence and terror: carrying out arbitrary arrests of thousands of Chadians, systematically torturing and murdering those he considered political opponents, and targeting specific ethnic groups for mass killings.

During Habré’s rule, reports of mass crimes and atrocities continued to come out. In November 1984 Amnesty International reported: “Government troops in Southern Chad have carried out hundreds of summary executions in the past two months, killing prisoners in custody and shooting unarmed civilians at random.”

Documents of Habré’s political police—the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS)—discovered by Human Rights Watch in 2001 revealed the names of 1,208 people who were killed or died in detention, and the names of 12,321 others who were victims of torture, arbitrary detention, and other human rights violations. A 1992 Truth Commission, set up by the government that replaced Habré, estimated that he was responsible for more than 40,000 deaths.

Habré’s secret police—the DDS—had been created and trained by the U.S. from the start. American officials made regular visits to DDS offices for purposes of “advising, or exchanging information”—at the same time, according to Chad’s 1992 Truth Commission, that the worst of the torture and murder was taking place.

In “Enabling a Dictator: The United States and Chad’s Hissène Habré, 1982-1990,” Human Rights Watch reports:

DDS logs confirm that an embassy official who liaised with the DDS visited the DDS headquarters at the height of one of the waves of repression. The DDS headquarters, which included a torture chamber, and Habré’s underground “Piscine” prison—a colonial-era swimming pool divided into cells and covered with a cement slab—were located in the capital N’Djaména, across the street from the USAID office.

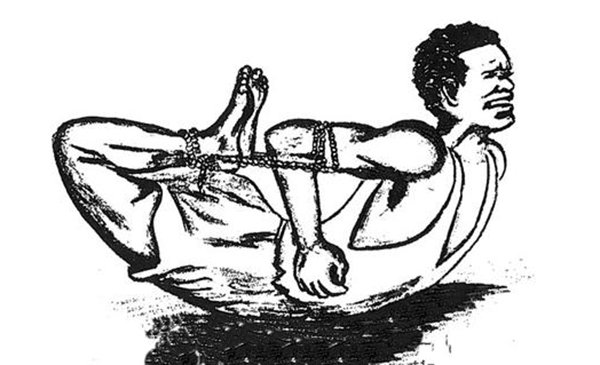

Over 25 years later, when Habré was tried in Senegal for crimes against humanity, 90 witnesses testified that he had thrown thousands of people into secret jails, where they were tortured and killed. The tortures people suffered included waterboarding, forced asphyxiation on the tailpipe of a car, and the “Arbatachar”—where all four limbs are tied behind the victim’s back, the cord yanked tight until the chest is thrust forward—which left some deformed, paralyzed, or unable to use their limbs at all.

During his eight bloody years in power, it’s estimated that Habré’s secret police killed tens of thousands, tortured as many as 200,000 and disappeared countless others. Yet during that time the U.S. never stopped providing him with tens of millions of dollars each year in military assistance, training, intelligence, and political support. That aid only stopped when Habré was driven from power in 1990.

THE CRIMINALS

Hissène Habré was put on trial in Senegal in 2016 and found guilty of crimes against humanity, summary execution, torture, rape, and sexual slavery. He was sentenced to life in prison.

President Ronald Reagan gave the go-ahead to the CIA to secretly fund Habré when he was already known as a brutal warlord hungering for power. To them he was “our man in Africa.” And Reagan continued his support year after year, despite the mounting evidence of atrocities committed against the Chadian people under Habré’s rule. In 1987 Reagan invited Habré for a special visit to the White House, where he said: “President Habré and I are convinced that the relationship between our countries will continue to be strong and productive, one which will serve the interests of both our peoples. It was an honor and a great pleasure to have had him here as our guest.”

CIA Chief William Casey and Secretary of State Alexander Haig played crucial roles in putting their “quintessential desert warrior” Hissène Habré in power. They also played key parts in ensuring that Habré was provided with all the covert aid he needed to remain in power, despite his growing mountain of crimes against humanity. A former director of Chad’s DDS said at his own torture trial in 2014 (which ended in a life sentence), “I was constantly assisted by a CIA agent who provided me with advice.”

The French government also fully supported Habré—supplying him with weapons, logistical support, and information. In addition, it carried out its own military operations to help force Libyan troops from Chad. French advisers worked with the military, and French intelligence also trained DDS and army officers in France as well as in Chad. This includes Idriss Déby, the current president, who forced Habré out in a 1990 coup. France was Chad’s largest financial contributor, investing $250 million per year.

Israel and Saudi Arabia were also a part of the coalition that trained and armed Chad’s security forces.

THE ALIBI

From the start of his presidency, Reagan had declared “international terrorism” a primary threat to world order, and targeted Libya’s Qaddafi as a prime supporter of terrorism. The U.S. justified its support for Habré in terms of its “global war on terrorism,” combating Soviet expansionism, and maintaining political stability in Chad and Central Africa.

As Habré’s atrocities began to come to light, the U.S. officials and intelligence operatives closest to Habré claimed they were unaware of the magnitude of his crimes. As the evidence became insurmountable in the years and decades following his ouster, the U.S. expressed shock and regret for what they might have contributed to that. After the verdict in Habré’s trial, Obama’s secretary of state, John Kerry, said, “This is also an opportunity for the United States to reflect on, and learn from, our own connection with past events in Chad.”

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE

Defending Chad was not Reagan’s principal concern. The U.S.’s actual motive was focused on encircling and undermining Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi. Throughout the 1980s, Habré was a centerpiece in that effort.

As Raymond Lotta put it, “The problem the U.S. imperialists had with Qaddafi was his close ties to the Soviet bloc [then the U.S.’s main imperialist rival]... the problem they had was assertiveness in supporting certain radical movements and groups that might benefit the Soviet bloc at a time when the rivalry between the U.S. and Soviet-led blocs was heading towards a global military showdown.”

U.S. support for Habré was aimed at preventing Libya from taking over northern Chad (or the entire country) and increasing its (and potentially Soviet) influence in neighboring countries. In 1983 Reagan said he was not only concerned with maintaining political stability in Chad, but that “the whole attitude of Qaddafi and his empire-building is of concern to anyone, but the main concern is to the surrounding African States”—which included Sudan, Niger, Nigeria, Egypt, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and Senegal. These were all considered “pro-Western,” and threatened by Libya.

For the U.S., Habré’s regime was also a weapon for weakening Libya. As Secretary of State Haig put it, working with Habré to launch a covert war against Libyan and pro-Libyan forces would “bloody Qaddafi’s nose” and “increase the flow of pine boxes back to Libya.” By 1987, Libyan forces had largely been driven from Chad.

Compared to these imperialist interests, concerns about human rights—or life—barely registered. As one former U.S. intelligence official who worked with Habré put it:

Little to no attention was paid to the human rights issues at the time for three reasons [...] (1) We wanted the Libyans out and Habré was the only reliable instrument at our disposal, (2) Habré’s record suffered only from the kidnapping (the Claustre Affair2), which we were content to overlook, and (3) Habré was a good fighter, needed no training, and all we had to do was supply him with material.

SOURCES

Michael Bronner, “Our Man in Africa,” Foreign Policy, January 24, 2014.

“Enabling a Dictator: The United States and Chad’s Hissène Habré, 1982-1990,” Human Rights Watch, June 28, 2016.

“Revolution Interviews Raymond Lotta: The Events in Libya in Historical Perspective... Muammar Qaddafi in Class Perspective... The Question of Leadership in Communist Perspective,” revcom.us, March 8, 2011.

Truth Commission: The Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes and Misappropriations Committed by Ex-President Habré, His Accomplices and/or Accessories, Duration: 1991‒1992, United States Institute of Peace.

“Chad profile—Timeline,” BBC, May 8, 2018.

William Blum, Rogue State—A Guide to the World’s Only Superpower (Common Courage 2000), pp. 151-52.

Bob Woodward, VEIL—The Secret Wars of the CIA, 1981-1987, Pocket Books, 1987

“Libyan Intervention in Chad, 1980-87,” GlobalSecurity.org.

1. See, American Crime Case #57: The 1973 CIA Coup In Chile, revcom.us, October 22, 2017. [back]

2. In 1974 Habré’s armed forces kidnapped three Europeans, including Françoise Claustre, a French anthropologist and wife of a French government official. Habré insisted on a ransom from the French and German governments in the form of cash, armaments, and medical supplies. In 1975, Habré’s forces executed a French captain who went to Chad to negotiate Claustre’s release. [back]

Over 25 years, thousands of people were jailed, tortured and killed at the hands of Habré. One of the tortures people suffered was the “Arbatachar”—where all four limbs are tied behind the victim’s back, the cord yanked tight until the chest is thrust forward. This left some victims deformed, paralyzed, or unable to use their limbs at all.

President Ronald Reagan gave the go-ahead to the CIA to secretly fund Habré, a brutal warlord hungering for power. In 1987 Ronald Reagan invited Habré to the White House. He said: “President Habré and I are convinced that the relationship between our countries will continue to be strong and productive, one which will serve the interests of both our peoples….”

Hissène Habré was put on trial in Senegal in 2016 and found guilty of crimes against humanity, summary execution, torture, rape, and sexual slavery. These three rape victims, seen here with their lawyer, testified at his trial about being raped repeatedly by his military forces. (Photo: AP)

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: