Case #15: Chicago 1919: The Racist Riot and the Righteous Resistance

| revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

THE CRIME

July 27, 1919. Late in the afternoon of a hot Chicago day, a Black teenager named Eugene Williams and some friends went out into Lake Michigan from an unofficial “colored” beach at 29th Street to cool off and have some fun—a simple act of the kind that has so often proved deadly for Black youth, from that time and before, on down to the present day.

The kids drifted across the invisible line to the adjacent “white” area. Here is how the anti-Black Chicago Daily Tribune described what happened at the time1:

A snarl of protest went up from the whites and soon a volley of rocks and stones were sent in his direction. One rock, said to have been thrown by George Stauber of 2904 Cottage Grove avenue, struck the lad [Williams] and he toppled into the water.

Colored men who were present attempted to go to his rescue, but they were kept back by the whites, it is said. Colored men and women, it is alleged, asked Policeman Dan Callahan of the Cottage Grove station to arrest Stauber, but he is said to have refused.

This brazen murder by racist whites backed by the cops sparked an immediate clash between Blacks and whites on the adjoining sections of the beach, which spread like wildfire through a large part of the city.

There are various accounts of what happened, but what is clear is that gangs of white youths, soldiers, sailors, and other white racists went on a rampage against Chicago’s small Black community, which was less than 5% of the city’s population. Again, from the Daily Tribune, under the subhead “Drag Negroes From Cars”:

Negroes who were found in street cars were dragged to the street and beaten. They were first ordered to the street by white men and if they refused the trolley was jerked off the wires....

News of the afternoon doings had spread through all parts of the south side by nightfall, and whites stood at all prominent corners ready to avenge the beatings their brethren had received. Along Halsted and State streets they were armed with clubs, and every Negro who appeared was pommeled.

Another account reported that “groups of whites had driven a truck at breakneck speed up south State Street, in the heart of the Black ghetto, with six or seven men in the back firing indiscriminately at the people on the sidewalks.”2 Black homes were set afire, especially those of families who had dared to move outside the Black Belt. According to the Chicago Defender (Chicago’s main Black paper), “[Black] Workers thronging the loop district to their work were set upon by mobs of sailors and marines roving the streets and several fatal casualties have been reported. Infuriated white rioters attempted to storm the Palmer house and the post offices, where there are a large number of [Black] employees....”3

This mass lynch-mob pogrom was fueled by social, political, economic, and demographic changes that were stressing and challenging the traditional white supremacist, highly segregated order in Chicago and across the U.S. The “Great Migration” of Black people from the South to the North had more than doubled Chicago’s Black population between 1909 and 1919—from 44,000 to 100,000—but housing remained rigidly segregated, often imposed through private “covenants” forbidding white homeowners from selling to Black people.

The new migrants seeking jobs found themselves in fierce competition with Chicago’s white residents, and the desperation of Black people was often used by big capitalist employers to bring down wages or to break strikes, further fueling resentment. This clash was especially sharp in Chicago’s sprawling stockyards.4 Meanwhile, World War 1 had just ended, and many returning Black veterans brought with them a defiant spirit and were less willing to tolerate open Jim Crow humiliation and brutality.

In Chicago (and many other cities), white youths were organized into racist gangs (the so-called “Athletic Clubs”) which had as part of their explicit principle that “they didn’t allow niggers in [their] neighborhood.” These gangs were closely tied to the Democratic Party machine in Chicago; in fact, Richard J. Daley, who went on to become Chicago’s most powerful mayor, emerged as a leader of one such gang after the 1919 pogrom.5

And the gangs were quite active in the years leading up to the 1919 pogrom. Between January 1918 to August 1919, there were 20 bombings of Black homes outside the Black Belt... but only two arrests.6 And they were itching to start a race war that would pit the small Black minority against the large white population. One gang even donned blackface and set fire to homes in a Lithuanian and Polish neighborhood in hopes of turning these new immigrants against Black people.7

All of this came into play in Chicago on July 27, 1919, in a storm of anti-Black violence in which thousands of white people participated while, for the most part, cops either stood idly by or actually helped the racists. And similar pogroms were unleashed in many other cities—from Washington, DC, to Charlotte, South Carolina. In DC, “200 sailors and marines marched into the city, beating African American men and women. A group of whites also tried to break through military barriers to attack African Americans in their homes.”8

But these racist pogroms did not go unresisted, in Chicago or elsewhere. Harry Haywood (who later became a communist) was just back from the war. When he saw what was happening, he and other vets set up in a strategically located apartment with a submachine gun and rifles to defend the neighborhood. In another incident, Haywood said that Black vets ambushed a truck that was speeding through the ’hood shooting at people. The vets

pulled in behind and opened up with a machine gun. The truck crashed into a telephone pole at Thirty-ninth Street; most of the men in the truck had been shot down and the others fled. Among them were several Chicago police officers—“off duty,” of course!9

And there were many instances of crowds of Black people freeing others from the clutches of the police or white mobs, as well as counterattacking against white areas that were concentrations of the racist assault, and against white-owned businesses in the Black Belt. Much of this resistance was armed. (As inevitably happens in such a chaotic situation, there were also some innocent white people who were attacked when they strayed into Black areas.)

And the same was true elsewhere. In Washington, DC, “Determined to fight back, a group of African Americans boarded a streetcar and attacked the motorman and the conductors. African Americans also exchanged gunfire with whites who drove or walked through their neighborhoods.”10

In Chicago, the anti-Black violence was cheered on by major newspapers and political institutions. The Chicago Daily Tribune focused on the small minority of white people who were hurt (or even were the “victims” of “insulting remarks”) by Black people. One Daily Tribune headline screamed about “A Crowd of Howling Negroes.” Another paper headlined an article “Negro Bandits Terrorize Town.”11

Moreover, the Chicago Police Department had a consistent practice of either not arresting white rioters at all, or arresting them and letting them go. In one incident, cops arrested five whites and a group of Blacks. The Blacks stayed in jail; the “five whites were released and their ammunition given back to them with the remark, ‘You’ll probably need this before the night is over.’”12 The “athletic clubs” were never prosecuted for their role in the violence, although the “Chicago Commission on Human Relations eventually concluded that without these gangs ‘it is doubtful if the riot would have gone beyond the first clash.’”13

And key figures wanted to amp things up even further. Joseph McDonough, a rising Democratic Party political figure who was “mentor” to the “Hamburg Athletic Club”—future-mayor Daley’s gang—claimed that police captains were telling South Side whites, “For God’s sake, arm. They are coming; we cannot hold them.” And McDonough told police chief John J. Garrity that “unless something is done at once I am going to advise my people to arm themselves for protection.”14

In the days following July 27, area cops called for all police and reserves in the city to concentrate around the Black Belt (as Chicago's Black ghetto was known), and thousands of National Guard as well as sheriffs from surrounding counties were brought in. That, together with heavy rains, brought relative calm, though sporadic fighting continued for another week.

By August 3, when the fighting ended, 38 people were dead (25 Blacks, 13 white) and at least 500 wounded; thousands of Black people (and some whites) had been driven from their homes.

But that was not the end of the assault on the Black community. The very next day, a special grand jury issued indictments for “rioting and murder”… against 17 Black people! The judge hearing the indictments “exhorted the jury to deal with [the riots] as anarchy” and promised “speedy trials” (i.e., rapid convictions) for the indicted Black people. Meanwhile, over 10,000 troops, police and deputies continued to patrol the Black community, and Black homeowners living on the edge of “the negro district” received letters warning them “to move within two days or their homes would be burned and bombed.”15

Nationally, this period of racist violence was dubbed “The Red Summer” by NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. The official death toll was 150 people, mainly Black.

For Black people, their sense of safety was utterly devastated, and for many it was a turning point towards radicalization. Harry Haywood had this realization: “I had been fighting the wrong war. The Germans weren’t the enemy—the enemy was right here at home.”16

THE ALIBI

During the frenzy of white lynch-mob violence, Chicago newspapers and political leaders either outright blamed Black people (as with the articles cited above depicting Black people as a “Howling Mob”) or emphasized the injuries to white people. Or they played the “violence on both sides” card, failing to distinguish between the organized, violent racist assault on Black people and their heroic resistance to that violence.

And they completely obscured the role of their own system in systematically preparing the ground for the pogrom with racist agitation, the organization of racist gangs and the complicity of the police. Instead, they drew the “lesson” that Black people and white people just can’t live together without fighting.

Since then, for the most part this massive anti-Black pogrom has been blotted out of history. In the whole city of Chicago, there is exactly one site commemorating what happened—a plaque affixed to a boulder near Lake Michigan that was paid for by suburban high school students.17

THE REAL MOTIVE

What lay behind the 1919 Chicago pogrom, and the whole “Red Summer” of anti-Black violence, was the need for the U.S. ruling class to maintain the brutal oppression of Black people, and the whole white supremacist hierarchy upon which U.S. society was built from even before its birth as a nation, under new conditions.

The Great Migration, the return of Black veterans from World War 1, and other social, economic, political, and demographic changes that were taking place confronted the ruling class with the “problem” of how to maintain Black people in an oppressed position outside the apparatus of racist sheriffs, KKK, and predatory white landowners that—more or less—had held Black people in the rural South “in check.”

Former rural peasants, moving into the cities to jobs where they would be super-exploited as the lowest-paid workers in the worst jobs—a source of enormous profit to U.S. capitalism for several generations to come—had to be beaten into submission through terror, their defiant spirit suppressed, and white people (including oppressed white people) enlisted to serve and identify with the whole oppressive order to carry this out.

One upshot of the 1919 violence was a conscious decision on the part of the Chicago authorities to replace informal segregation with a more formal system. As a Chicago Tribune article earlier this year noted: “[A]fter the riots, the city—meaning white Chicago—essentially decided to separate the races officially. ‘The city’s response to the cataclysmic events of the riot in many ways was to double down on segregation as a solution to keep the peace,’... Housing segregation of course has been a dominant shaping factor within the city and has largely structured it as a dual and unequal city in relation to whites and blacks.”18 In 1920, the Chicago Realtor’s Board voted “unanimously to punish by ‘immediate expulsion’ any member who sold property to a black on a block where there were only white owners.”19

THE CRIMINALS

The mainstream newspapers, which whipped up racist sentiment before and during the 1919 racist riots.

The “Athletic Clubs” of racist white youths who spearheaded the pogrom, as well as the all-too-broad sections of white people, numbering well into the thousands, at least, who joined in, and the hundreds of thousands of others who stood aside and were thus complicit in this orgy of racist violence.

The Chicago city political structure, including the Democratic Party (and future mayor Richard J. Daley), which organized and ran the “Athletic Clubs” as a conscious tool for maintaining power on a white supremacist basis in Chicago.

The real estate industry, which maintained and profited from speculation and then whipped up and profited off of white fear and white flight, and the big capitalist factory, mill, and packinghouse owners who pitted Blacks against white workers.

The whole damn system of capitalism, which arose and throve on the enslavement of Black people and has continued to find yet new forms of oppression from which to increase its power and profit.

1. “A Crowd of Howling Negroes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1919. [back]

2. Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Communist, by Harry Haywood, chapter 5, “History Is A Weapon,” Chicago, Liberator Press, 1978. [back]

3. From the Chicago Defender, ”Ghastly Deeds of Race Rioters Told,” 1919, cited by “History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web.” [back]

4. “Chicago and Its Eight Reasons,” by Walter White, October 1919. [back]

5. American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley—His Battle for Chicago and the Nation, by Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor, New York, Back Bay Books, 2001, Excerpt. [back]

6. “Chicago and Its Eight Reasons,” Walter White. [back]

7. Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, 2005, “Race, Ethnicity and White Identity.” [back]

8. “The Red Summer of 1919, Explained,” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Teen Vogue, April 8, 2019. [back]

9.Black Bolshevik, Harry Heywood. [back]

10. Teen Vogue, “The Red Summer of 1919, Explained” [back]

11. “Chicago and Its Eight Reasons,” Walter White. [back]

12. “Chicago and Its Eight Reasons,” Walter White. [back]

13. American Pharaoh, Cohen and Taylor. [back]

14. American Pharaoh, Cohen and Taylor. [back]

15. “Indict 17 Negro Rioters,” New York Times, August 4, 1919. [back]

16. Teen Vogue, “The Red Summer of 1919, Explained” [back]

17. “‘Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots’ looks to bring city to terms with a chilling summer 100 years ago,” Chicago Tribune, January 18, 2019. [back]

18. “‘Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots’ looks to bring city to terms with a chilling summer 100 years ago,” Chicago Tribune. [back]

19. American Pharaoh, Cohen and Taylor. [back]

Watch BA’s whole speech, Why We Need An Actual Revolution And How We Can Really Make Revolution

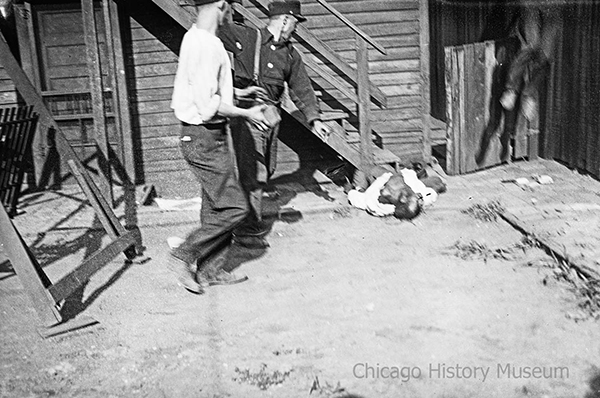

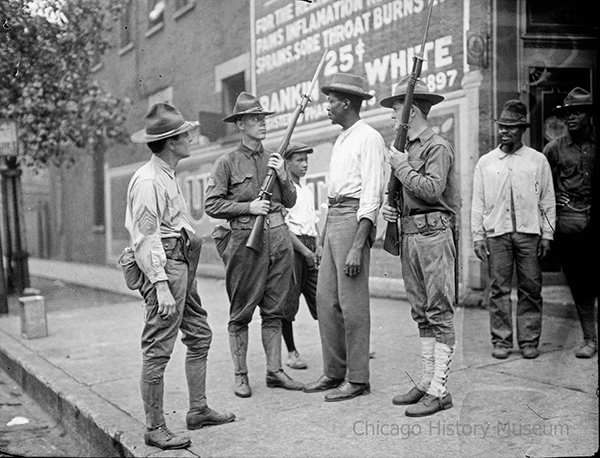

All photos: Jun Fujita, Chicago History Museum

White men stoning an African-American man during the 1919 racist riot in Chicago.

Black victim being stoned and bludgeoned during the racist riot in Chicago, Illinois, 1919.

Armed National Guard troops and Black men face off on a sidewalk during the 1919 racist riot in Chicago, 1919.

Armed National Guard troops and a crowd of Black people, Chicago, 1919.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: