Excerpts on Imperialism and the Kurdish People

from Larry Everest, Oil, Power & Empire—Iraq and the U.S. Global Agenda1

| revcom.us

From CHAPTER 2: IRAQ IS NOT PRESENT AT THE CREATION

Incorporating—and Subordinating—the Kurds

In 2003, Saddam Hussein’s history of brutality against Iraq’s Kurdish population would feature prominently in Washington’s indictment of Ba’ath rule and its case for “regime change.” What Bush and company hypocritically ignored and what is rarely mentioned in mainstream coverage, however, was Britain’s role in deepening Kurdish oppression and the U.S. role in perpetuating it.

The Kurdish people have lived in the rugged mountains and valleys of northeast Iraq, western Iran, eastern Turkey and northeast Syria since the 7th century BC. This contiguous area, often called “Greater Kurdistan,” is nearly the size of Iraq. The Kurds are historically a pastoral and nomadic people, raising sheep and goats. Over time many have become peasants, others urban dwellers. Today numbering some 25 to 30 million, Kurds make up the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East, behind Arabs, Persians, and Turks. The Kurds converted to Islam in the 7th century AD (around 80 percent are Sunnis, the rest Shi’as), while retaining their national identity. The Kurdish language, a branch of Indo-European family closely related to Iran’s Farsi and Afghanistan’s Dari, is distinct from Arabic and Turkic. Kurdish culture, dress, and history are also distinct.

The Ottomans ruled most of Kurdistan from the 1600s until their empire collapsed following World War I. In 1880, during one Kurdish uprising, Sheikh Ubaidullah wrote the British:

“The Kurdish nation is a nation apart. Its religion is different from that of others, also its laws and customs.... We want to take matters into our own hands. We can no longer put up with the oppression which the governments [of Persia and the Ottoman Empire] impose on us.”33

Unfortunately, subsequent history, explored here and below, would demonstrate that neither the British nor the American empires, despite their claims to benevolence, would bring justice to the Kurds.

Like the Arabs, the Kurds had been promised independence by the world’s major powers following World War I. Point 12 of President Woodrow Wilson’s 1918 “Fourteen Points” declared that “the nationalities now under Turkish rule should...be assured...an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.”34 The August 1920 Treaty of Sevres formally recognized, for the first time, that the Kurds formed a distinct nationality and forced Turkey to renounce possessions comprised of non-Turkish populations, such as Kurdistan, and stipulated that the Kurds be given “local autonomy.”35

However, Kurdish aspirations, like those of the Arabs, were betrayed and then suppressed for British imperial interests. The Treaty of Sevres would have effectively dismembered Turkey—partitioning it between Italy and Greece, with independent states (or autonomous areas) in the Armenian and Kurdish areas.36 However, the treaty was never ratified and Turkish nationalists, led by Ataturk, rose in revolt and defeated the Greek Army in 1923, making the Sevres agreement moot.

A new treaty was signed by the allies and the new Turkish government at Lausanne, Switzerland on July 23, 1923. It made no mention of Kurdish independence. Instead, it ceded much of Kurdistan to the new Turkish government, which promptly banned all Kurdish schools, organizations, and publications. For decades after, Turkey refused to even acknowledge Kurdish ethnicity—instead calling them “mountain Turks”—and outlawed the Kurdish language. Ataturk’s government brutally crushed a 1925 Kurdish revolt against the Lausanne Treaty, and government assaults, mass deportations, and massacres against the Kurds continued during the 1920s and 1930s.37 Turkey, one of the U.S.’s closest allies in the region, has continued its grim oppression of the Kurds to this day. The Los Angeles Times reported that in December 2001, during the buildup to the 2003 war on Iraq, Turkish military police began scouring Kurdish villages and checking birth records for any newborns given traditional Kurdish names, and then forcing their parents to rename and re-register them with Turkish names. The Turkish regime warned that use of traditional Kurdish names would be considered “terrorist propaganda.”38

Kurds in Iraq also rose for self-rule. In 1919, Sheikh Mahmoud Barzinji declared himself the ruler of an independent Kurdistan and began administering the area around Suleimanieh in north east Iraq. London’s main political officer in Baghdad wrote at the time: “the Kurds wish neither to continue under the Turkish government nor to be placed under the control of the Iraqi government.” He estimated that 80 percent of the Kurds supported independence.39 The British quickly removed Barzinji from power.40 Subsequent revolts were also crushed by British forces in 1922 and by the RAF bombing of Suleimanieh in 1924.

The British were fundamentally no more interested in Kurdish self-determination than the Turks. Rather, they were interested in making sure that the former Ottoman Province of Mosul, an area populated by Kurds and Turkomans, was incorporated into the new state of Iraq, not Turkey. The reason was oil. The British feared that without the oilfields near the cities of Mosul and Kirkuk, the new state of Iraq would not be economically viable.41

The British promised the Kurds that the new Iraqi government under their control would recognize “the right of the Kurds who live within the frontiers of Iraq to establish a Government within those frontiers.” And in December 1925, the League of Nations decided in favor of the British: the Mosul region was incorporated into the new state of Iraq with the understanding that the British, whose mandate would continue for 25 years, would ensure Kurdish rights. “The desire of the Kurds that the administrators, magistrates and teachers in their country be drawn from their own ranks, and adopt Kurdish as the official language in all their activities,” the League declared, “will be taken into account.”42

This was the first and only time an international body formally promised the Kurds, of any country, a degree of autonomy. Yet such promises proved as empty as the others made by the British and the League to the peoples of the Middle East. Nor has the League’s successor, the United Nations, ever taken serious steps to uphold the Kurdish peoples’ right to self-determination. Today the Kurdish people remain the largest ethnic group in the world never to have achieved statehood.

Cobbling Together a Country

The new state of Iraq that emerged from these post-war years of foreign rivalry and maneuvering was born with deep internal fault lines, which have frequently been exploited by outside powers in the decades since. Britain had no desire to see a strong state arise in the midst of the world’s greatest oil fields. The British had created Iraq by combining three demographically distinct administrative units of the Ottoman Empire: Basra in the Shi’a south, Baghdad in the Sunni center, and Mosul in the Kurdish north.

The result was a patchwork of polities: the Kurdish areas comprised roughly 17 percent of Iraq’s 438,446 square kilometers, and some 20 percent of its population. Sixty percent of Iraqis were Shi’a Arabs living in the south; and some 20 percent were Sunni Arabs living in the center. Turkomans, who mainly live in the north, made up some 2.4 percent of the population, Persians 1.7 percent, and Chaldean Christian and Assyrians another 3.6 percent. In A History of the Modern Middle East, author William Cleveland notes that these groups “did not constitute a political community in any sense of the term,” yet the formation of Iraq drastically changed their political worlds.43

The British held this agglomeration together by relying on the Sunni Arab-based monarchy, backed by British arms, to rule over the Shi’a south and the Kurdish north. This oppressive configuration was supported by London and Washington—most glaringly in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War as explored in chapter 5—up until the 2003 overthrow of the Hussein regime. The point of this arrangement was to prevent the emergence of a Kurdish state, which could threaten the stability of Iran to the east and Turkey to the north; and also to prevent the rise of Shi’a power. Prior to 1979, this could have destabilized the Shah’s rule in Iran; after his fall it could have increased the regional influence of Iran’s Islamic Republic. Today, the U.S. occupation of Iraq has not resolved these deep ethnic and religious tensions; instead, they have the potential to help turn Washington’s conquest into a quagmire.

The new state lay at the head of the Persian Gulf, soon to become the heart of the world oil industry, and was bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to the south, and Jordan and Syria to the west. Three of these states—Turkey, Iran, and Syria, shared overlapping Kurdish populations with Iraq—a demographic that the U.S. has frequently exploited to weaken Iraq.

In 1932, Britain’s League of Nations mandate ended and Iraq became formally independent, but London still effectively ruled. Its armed forces remained in Iraq to ensure the continuation of the monarchy, which was widely hated and rightly considered a tool of British interests.

There were repeated uprisings against the British and the King, which British forces violently put down. In July 1931, RAF planes buzzed towns along the Euphrates River to intimidate an Iraqi general strike. That year and the next, the RAF bombed Kurdish rebels in Barzan.44 British planes were deployed against numerous uprisings, mainly in Kurdish areas, between 1936 and 1941. And during World War II, British troops invaded and occupied Iraq to depose the nationalist and pro-German government of Prime Minister Rashid Ali, who had seized power in 1941 with support from reformist intellectuals and nationalist army officers. During the war, preventing Iraq’s oil from falling into German hands became an important military objective.

From CHAPTER 3: SADDAM HUSSEIN’S AMERICAN TRAIN

The CIA Forms a “Health Alterations Committee”

The U.S. also sought to weaken Qasim [an Iraqi general who took power in 1958, overthrowing Iraq's pro-imperialist monarchy] by encouraging a Kurdish insurgency. The Kurds had initially welcomed the 1958 revolution, but it soon became clear that Qasim and the military would not grant their demands for autonomy and a share of the country’s oil wealth. By 1960, the U.S. and the Shah of Iran were arming the Kurds and supporting their revolt.53 According to Morris, the CIA plotted against Qasim and tried—unsuccessfully—to assassinate him:

In Cairo, Damascus, Tehran and Baghdad, American agents marshaled opponents of the Iraqi regime. Washington set up a base of operations in Kuwait, intercepting Iraqi communications and radioing orders to rebels.... The CIA’s “Health Alteration Committee,” as it was tactfully called, sent Kassem a monogrammed, poisoned handkerchief, though the potentially lethal gift either failed to work or never reached its victim.54

....

Two years earlier, in 1961, the U.S. had encouraged the Kurds to rebel against Qasim. Now, in April 1963, just months after the Ba’ath massacre [of thousands of members of the Iraqi Communist Party, with CIA assistance, as part of their coup against Qasim], the U.S. turned against the Kurds and flew arms from Iran and Turkey to northern Iraq to help the new Ba’ath regime put them down. American and British companies were also pleased: “Soon, Western corporations like Mobil, Bechtel and British Petroleum were doing business with Baghdad,” Morris reports.70

....

Playing the Kurdish “Card” (Again!)

To hear the Bush II administration tell it, Iraq’s Kurds could have no better allies than their self-proclaimed friends in Washington. Bush and company repeatedly denounced the Hussein regime’s “persecution of its civilian population, including Shi’a, Sunnis, Kurds, Turkomans and others,” as Bush put it before the United Nations in September 2002, and argued that war, conquest, and regime change were needed to assure Kurdish freedoms.97

The proponents of the 2003 war never saw fit, of course, to mention the actual, sordid record of Washington’s manipulation and betrayal of the Kurds during the 1970s, which we delve into below. That history not only makes U.S. promises ring hollow and hypocritical, but casts Washington’s true intentions toward the Kurds in a starkly different light.

In 1972, Nixon, Kissinger and Iran’s Shah also came up with a cynical plan to deal with its concerns in the Persian Gulf: encouraging an insurgency by Iraq’s Kurds in order to weaken Baghdad. In May, Nixon and Kissinger visited Moscow and promised that the U.S. would join the Soviets to “promote conditions in which all countries will live in peace and security and will not be subject to outside interference.” Seymour Hersh, a long-time investigative journalist for the New York Times and later the New Yorker, writes in his biography of Kissinger that, “The next day, Nixon and Kissinger flew to Tehran and made a secret commitment to the Shah to clandestinely supply arms to the Kurdish rebel faction inside Soviet-supported Iraq....”98 The goal, Kissinger later explained, was for the Shah to “keep Iraq occupied by supporting the Kurdish rebellion within Iraq, and maintain a large army near the frontier.”99

Since Iraq’s creation by the British, its Kurdish population has suffered systematic discrimination and oppression. Much of Iraq’s oil flows from fields around Kirkuk in Iraqi Kurdistan. Yet Iraqi Kurds saw few benefits from Iraq’s petroleum wealth and had no voice in its oil policy. Kurdistan remained undeveloped, with fewer industries, roads, schools, and hospitals than the rest of Iraq. Kurds were discriminated against in government employment and had little control over even their local affairs.

Following the Ba’ath takeover in 1968, the new regime promised Kurds that their lot would improve. Iraq’s new 1970 constitution recognized “the national rights of the Kurdish People and the legitimate rights of all minorities within the unity of Iraq.” A 1974 “Law for Autonomy in the Area of Kurdistan” promised that Kurdish would be an official language, used in Kurdish schools.100 These actions marked Iraq’s broadest official recognition of Kurdish identity and rights. (In contrast, neighboring Iran and Turkey, then staunch U.S. allies, have never even formally recognized the Kurds as a distinct nationality, let alone promised them national rights.)

However, during negotiations in 1971 between the Ba’ath regime and Kurdish representatives, it became clear that the key issues of Kurdish control of local security forces, receiving a fair portion of Iraq’s oil income, and sharing national power were not on the table. The Ba’ath also began encouraging Iraqi Arabs to move to Kurdistan and attempted to assassinate Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani.101 Barzani, who had been in contact with the U.S. and the Shah (and perhaps Israel) since the early 1960s, turned to them once again for help against Baghdad. Barzani even promised the Washington Post that if the U.S. backed the Kurdish struggle, “we are ready to do what goes with American policy in this area if America will protect us from the wolves. If support were strong enough, we could control the Kirkuk field and give it to an American company to operate.”102

The Kissinger-Shah plan went into effect in 1972. Iran and the U.S. encouraged the Kurds to rise against Baghdad and provided them millions of dollars in weapons, logistical support, and funds. Over the next 3 years, $16 million in CIA money was given to Iraq’s Kurds, and Iran provided the Kurds with some 90 percent of their weapons, including advanced artillery.103

The U.S. goal, however, was neither victory nor self-determination for Iraqi Kurds. The CIA feared such a strategy “would have the effect of prolonging the insurgency, thereby encouraging separatist aspirations and possibly providing to the Soviet Union an opportunity to create difficulties” for U.S. allies Turkey and Iran.104 A Congressional investigation of CIA activities, headed by New York Congressman Otis Pike, concluded that “none of the nations who were aiding [the Kurds] seriously desired that they realize their objective of an autonomous state.”105 Rather, the U.S. and the Shah sought to weaken Iraq and deplete its energies. According to CIA memos and cables, they viewed the Kurds as “a card to play” against Iraq, and “a uniquely useful tool for weakening [Iraq’s] potential for international adventurism.”

To this end, Iran instituted “draconian controls” on its military assistance and never gave the Kurds more than three days worth of ammunition in order to deny them the freedom of action needed for victory.106 At one point in 1973, Kissinger personally intervened to halt a planned Kurdish offensive for fear it would succeed and complicate U.S. machinations in the wake of the October Arab-Israeli War.107 The Pike investigation concluded:

The president, Dr. Kissinger, and the Shah hoped that our clients would not prevail. They preferred instead that the insurgents simply continue a level of hostilities sufficient to sap the resources of our ally’s [Iran’s] neighbouring country. The policy was not imparted to our clients, who were encouraged to continue fighting.108

“Ours Was a Cynical Enterprise”

By 1975, the Kurdish insurgency posed the gravest threat the Ba’ath Regime had yet faced. Some 45,000 Kurdish guerrillas, aided by two Iranian divisions, had pinned down 80 percent of Iraq’s 100,000 troops, severely straining Iraq’s economy and military.109 Kissinger and the Shah wanted neither all-out war, nor the collapse of the Iraqi regime. Rather, they sought to force Iraq to curb its anti-Israeli Arab nationalism and to pry it from its Soviet patrons, demonstrating to others in the region that being a Soviet client didn’t pay. The Shah also wanted to prove that Iran was the Gulf’s strongest power and a reliable regional gendarme for the U.S., as well as to renegotiate the Sa’dabad Pact of 1937, which had given control of the entire Shatt al Arab waterway between the two countries to Iraq.110

The Shah planned to abandon the Kurds “the minute he came to an agreement with his enemy over border disputes,” one CIA memo noted. Eight hours after Iraq did agree to U.S.-Iranian terms, which were formalized in the Algiers Agreement of March 1975, the Shah and the U.S. cut off aid—including food—and closed Iran’s border, cutting off Kurdish lines of retreat.111

The Kurds had no idea that they were about to be abandoned. But Iraq knew, and the next day it launched an all-out, “search-and-destroy” attack. The Kurds, who had been led to believe that the U.S. was acting as a “guarantor” against betrayal by the Shah, were taken by complete surprise. Deprived of Iranian support, Kurdish forces were quickly decimated and between 150,000 and 300,000 Kurds were forced to flee into Iran.112

The U.S. coldly betrayed its erstwhile Kurdish “allies,” but even then, as the Pike Commission sardonically noted, “The cynicism of the U.S. and its ally had not yet completely run its course.” Barzani had written to Kissinger, pleading desperately for help. Kissinger didn’t bother replying.

Washington then “refused to extend humanitarian assistance to the thousands of refugees created by the abrupt termination of military aid,” the Pike Commission reported. One CIA cable acknowledged, “[O]ur ally [Iran] was later to forcibly return over 40,000 of the refugees and the United States government refused to admit even one refugee into the United States by way of political asylum even though they qualified for such admittance.”113

The U.S.-Iranian covert campaign further poisoned relations between Baghdad and Iraq’s Kurds. The Pike Commission concluded that if the U.S. and the Shah hadn’t encouraged the insurgency, the Kurds “may have reached an accommodation with the central government, thus gaining at least a measure of autonomy while avoiding further bloodshed. Instead, our clients [the Kurds] fought on, sustaining thousands of casualties and 200,000 refugees.”114

Baghdad also retaliated with a massive pacification campaign: some 250,000 Kurds were forcibly relocated to central and southern Iraq, while many Arab Iraqis were forced to move to into traditionally Kurdish areas.115

In what became an infamous remark, Kissinger dismissed the Pike Commission’s concerns: “Covert action,” he said, “should not be confused with missionary work.” Nonetheless, the Commission concluded, “Even in this context of covert operations, ours was a cynical enterprise.”116 It is important to note here that as these events were taking place (beginning in September 1973), Kissinger’s top aide was General Brent Scowcroft, who would later become National Security Advisor under Bush, Sr. and an architect of the 1991 Persian Gulf war on Iraq. It is also important to note that if the U.S. government had had its way, the Pike Commission’s damning exposures would have never seen the light of day. First, the House of Representatives voted not to release the document. Then, when CBS correspondent Daniel Schorr obtained a leaked copy and gave it to the Village Voice, he was promptly fired by CBS and threatened with contempt of Congress for refusing to reveal his sources. A new Director of Central Intelligence had just been appointed when this attempted cover-up took place. His name was George H.W. Bush.117

As we’ll explore in the next chapter, the United States government again resorted to a cynical “no win” strategy during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s with even more horrific consequences for Iranians, Iraqis and Kurds.

From CHAPTER 4: ARMING IRAQ—DOUBLE-DEALING DEATH IN THE GULF

Gas Massacres in Kurdistan

In 2003, the heinous gassing of Iraq’s Kurds during the Iran-Iraq War ranked high on the Bush, Jr. administration’s list of charges against the Hussein regime. Yet when these attacks were actually taking place, the U.S. government was not only supporting the Hussein regime, it was directly complicit in the gas massacres themselves.

During the war, Iraq’s Kurds took advantage of Baghdad’s focus on Iran to take control of Kurdish areas near the Iranian and Turkish borders. When Iranian forces moved into sections of Iraqi Kurdistan, as they sometimes did, they were often aided by Kurdish forces. By 1986, Baghdad held only the cities in Kurdistan, while Kurdish peshmergas controlled the surrounding countryside. In the midst of war, with the regime under great stress, the Kurdish insurgency forced Iraq to divert troops from the Iranian front and again posed a serious challenge to Baghdad. It responded viciously.

In 1983, Hussein put his cousin Ali Hasan al-Majid in charge of reasserting Ba’ath control, and he earned the sobriquet “Chemical Ali” for his murderous efforts. One of his first actions was rounding up some 8,000 males from the clan of Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) leader Masoud Barzani. They were never seen again.99 Kurds claim that the Hussein regime first used chemical weapons against them a year later. Chemical attacks further escalated in the spring of 1987.

Beginning in February 1988, as the war was winding down and momentum had shifted back to Iraq, the Hussein regime unleashed its “Al-anfal” (spoils of war) campaign—a seven-month rampage of murder, destruction, and scorched-earth vengeance against Iraq’s Kurds. Chemical attacks were stepped up, fields were destroyed, villages bulldozed, and survivors forcibly transferred to government resettlement camps outside of Kurdistan.

Charles Tripp, author of A History of Iraq, writes that by the time the campaign ended in August 1988, the Kurdish resistance had been crushed and “roughly 80 percent of all the villages had been destroyed, much of the agricultural land was declared ‘prohibited territory’ and possibly 60,000 people had lost their lives.”100

An estimated 3,800 Kurdish villages—the foundation of Kurdish life—were affected. In the 12 months from March 1987 until March 1988, Kurds were subjected to chemical attacks on 211 separate days.101 When I traveled around Suleiymeniah in Iraqi Kurdistan in the summer of 1991, I saw piles of stone rubble where Kurdish villages had once stood—grim testimony to the ferocity of the regime’s campaign.

The most notorious Iraqi attack took place on March 16, 1988 in the Kurdish town of Halabja. Iranian troops and Kurdish fighters had taken control of Halabja, some 15 miles from the border with Iran, and Iraq mounted a chemical weapons counter-attack to retake it. Some 5,000 Kurds were massacred in a few hours by a lethal combination that may have included mustard gas, cyanide, and the first recorded military use of nerve gas. People reportedly died where they had been standing, and bodies littered the streets.102

Independent journalist and Democracy Now! contributor Jeremy Scahill reports that in 1991 U.S. intelligence sources told the Los Angeles Times that they believed U.S.-built helicopters had been used to drop chemical bombs.103

Washington’s Silence and Complicity

In September 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell made a much-publicized trip to Halabja to visit the mass graves of those killed in the Hussein regime’s gassing; he even lit candles in memory of the victims. Given Washington’s complicity in creating those mass graves—and Powell’s own as a Defense Department official in the Carter, Reagan and Bush I administrations—his posturing in Iraqi Kurdistan was yet another display of the shameless hypocrisy of those running the U.S. empire.104

Throughout the 1980s, the U.S. supported attacks on Kurds throughout Greater Kurdistan, and steadfastly opposed recognizing their basic rights, let alone self-determination. This was done in service of overall U.S. objectives: preserving the “territorial integrity” and ruling governments of Iraq, Iran and Turkey and thus a regional balance of power that maintained U.S. dominance.

Iran’s Kurdish population rose up with millions of other Iranians to overthrow the hated Shah in 1979, but when they demanded their national rights, the U.S. government publicly supported the Khomeini regime’s efforts to crush them. This was brought home to me during trips to Iranian Kurdistan in 1979 and 1980, when, traveling with Iranian peshmergas, we were forced to drive with lights out in the dead of night to evade U.S. fighter jets, sold to the Shah and then utilized by the Khomeini regime, which streaked overhead strafing Kurdish positions along our route.

The picture was similar in Turkey. Its Kurdish population rose against the dictatorial Turkish regime in 1984, and the U.S. supported Ankara’s brutal suppression campaign with increased U.S. aid, which included supplying 80 percent of Turkey’s heavy weapons.105

Former U.S. Marine and UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter says that the U.S. assisted the Hussein regime in its chemical attacks on the Kurds: “Wafiq Samarai the former head of the Iraqi intelligence service responsible for Iran—I have met with him many times—and he has said that U.S. advisers were sitting there as Iraq planned the inclusion of chemical weapons in the Anfal offensive [of 1987-88].”106 Throughout the Iran-Iraq War, the U.S. maintained a “no-contacts” policy and refused to even meet with Iraqi Kurdish representatives. Washington’s approach was spelled out in the recently declassified, National Security Directive 26 (NSD-26), signed by President George H. W. Bush in October 1989:

We should oppose Iraqi military activities against the civilian population and the destruction of hundreds of villages in Kurdistan. But bearing in mind the historical context, in no way should we associate ourselves with the 60-year-old Kurdish rebellion in Iraq or oppose Iraq’s legitimate attempts to suppress it. 107

NSD-26 stated that Iraqi use of chemical or biological weapons or development of nuclear arms, would “lead to economic and political sanctions,” but these provisions were not enforced because they conflicted with overall U.S. strategy.108 For instance, after the gassing at Halabja, Secretary of State Schultz condemned the attack as “abhorrent and unjustifiable,” and the Senate passed the “Prevention of Genocide Act of 1988,” which would have imposed economic sanctions on Iraq (reflecting concerns of some strategists that the Hussein regime might not be a reliable client). The Reagan and Bush administrations, however, were still committed to turning Iraq into a strategic ally and blocked any action against Baghdad. U.S. officials argued that sanctions were “premature” because Washington needed “solid, businesslike relations” with Iraq. As one government memo stated, “there should be no radical policy change now regarding Iraq.”109 No sanctions were imposed and the “Genocide Act” died in Congress.

Instead, U.S. aid and trade increased. Guaranteed U.S. agricultural exports to Iraq peaked in 1988 at $1.1 billion. By early 1990, Iraq had become America’s third leading Middle East trade partner, after Saudi Arabia and Israel, purchasing $433.6 million worth of U.S. goods. The U.S., meanwhile, was importing 500,000 barrels of Iraqi oil a day by 1988.110

FOOTNOTES:

From Chapter 2

33. John Bulloch and Harvey Morris, No Friends but the Mountains: the Tragic History of the Kurds (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 73. [back]

34. Simons, 297. [back]

35. Gerard Chaliand, ed., People Without A Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan (London: Zed Press, 1980), 12. [back]

36. Peter Sluglett, “The Kurds,” in Saddam’s Iraq: Revolution or Reaction?, Committee Against Repression and for Democratic Rights in Iraq, 2nd ed., (London: Zed Books, 1989), 179. [back]

37. Chaliand, People Without A Country, 235; Sluglett, 179-80. [back]

38. Richard Boundreau, “Nameless Kurds of Turkey,” Los Angeles Times, January 30, 2003. [back]

39. Vanly, 159. [back]

40. Middle East Watch, Human Rights in Iraq (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990), 71. [back]

41. Middle East Watch, 72. [back]

42. Middle East Watch, 72. [back]

43. Cleveland, 201. [back]

44. Simons, 217. [back]

From Chapter 3

53. Blum, Rogue State, 134; Lee F. Dinsmore, “Regrets for a Minor American Role in a Major Kurdish Disaster,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, May/June 1991, 9. [back]

54. Morris, New York Times, March 14, 2003. [back]

70. Aburish, 59; Morris, New York Times, March 14, 2003. [back]

97. Bush, Wall Street Journal, September 12, 2002. [back]

98. Seymour M. Hersh, The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House (New York: Summit Books, 1983), 542. [back]

99. Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, 674-75. [back]

100. Middle East Watch, 70. [back]

101. Tripp, 200-201. [back]

102. Dinsmore, Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, May/June 1991; Washington Post, June 22, 1973 cited in Simons, 302. [back]

103. Bulloch and Morris, No Friends But the Mountains, 138-39. [back]

104. CIA: The Pike Report (United Kingdom: Spokesman Books, 1977), 211. Extensive excerpts from the Select Committee on Intelligence, or Pike report, were also published in the New York Times and the Village Voice. “The CIA Report the President Doesn’t Want You to Read,” Village Voice, February 16, 1976; “House Committee Finds Intelligence Agencies Generally Go Unchecked” and “Intelligence Report Leaks Denounced by White House,” articles by Nicholas M. Horrock and John M. Crewdson, New York Times, January 26 and 27, 1976. [back]

105. Pike Report, 214. [back]

106. Vanly, 187. [back]

107. Bulloch and Morris, No Friends But the Mountains, 140. [back]

108. Pike Report, 197. [back]

109. Dilip Hiro, The Longest War (New York: Routledge, 1991),16; Simons, 303. [back]

110. Vanly, 186. [back]

111. Vanly, 187. [back]

112. Pike Report, 197-98; Cleveland, 398-99; Vanly, 189. [back]

113. Pike Report, 198, 217. [back]

114. Pike Report, 197. [back]

115. Cleveland, 398-99. [back]

116. Pike Report, 198. [back]

117. Otis Pike, “We’ve Given Them False Hope Before,” San Francisco Examiner, April 10, 1991; Daniel Schorr, “1975 Background to Betrayal,” Washington Post, April 7, 1991, D3; Christopher Hitchens, “Minority Report,” The Nation, May 6, 1991, 58; all cited in Tony Murphy, “Encouraging Rebellion: The Cynical Use of the Kurds and the Shiites,” in “High Crimes and Misdemeanors: U.S. War Crimes in the Persian Gulf,” Research Committee of the San Francisco Commission of Inquiry of the International War Crimes Tribunal, 1991. [back]

From Chapter 4

99. Tripp, 243. [back]

100. Tripp, 243. [back]

101. Bulloch and Morris, No Friends but the Mountains, 142. [back]

102. Bulloch and Morris, No Friends but the Mountains, 142. [back]

103. Scahill, ZNET, August 4, 2003 [back]

104. Jonathan Wright (Reuters), “Powell Visits Mass Grave of Hussein’s Victims,” Washington Post, September 15, 2003. [back]

105. Cleveland, 506; Noam Chomsky, “Prospects for Peace in the Middle East,” speech at the University of Toledo, March 4, 2001 (www.matrixmasters.com/wtc/chomsky); Middle East Watch, 79-80. In 1982, Iraq signed an agreement with Turkey authorizing Turkish forces to enter Iraq in pursuit of Kurdish rebels from Turkey, or to conduct joint operations with Iraqi forces against Iraqi Kurds. This agreement helped Iraq deploy more forces against Iran. Clark, 6. [back]

106. Phil Donahue Show, January 13, 2003, MSNBC. [back]

107. Jentleson, 104, emphasis in original. [back]

108. Phythian, 42. It also urged that the U.S. “should pursue and seek to facilitate, opportunities for US firms to participate in the reconstruction of the Iraqi economy, particularly in the energy area, where they do not conflict with our non-proliferation and other significant objectives,” foreshadowing the 2002-2003 discussion of U.S. control of Iraq’s petroleum industry following “regime change” in Baghdad. [back]

109. Jentleson, 69. [back]

110. Ridgeway, 13-14; Teicher and Teicher, 393. [back]

1. Larry Everest, Oil, Power & Empire – Iraq and the U.S. Global Agenda (Common Courage Press, 2004) [back]

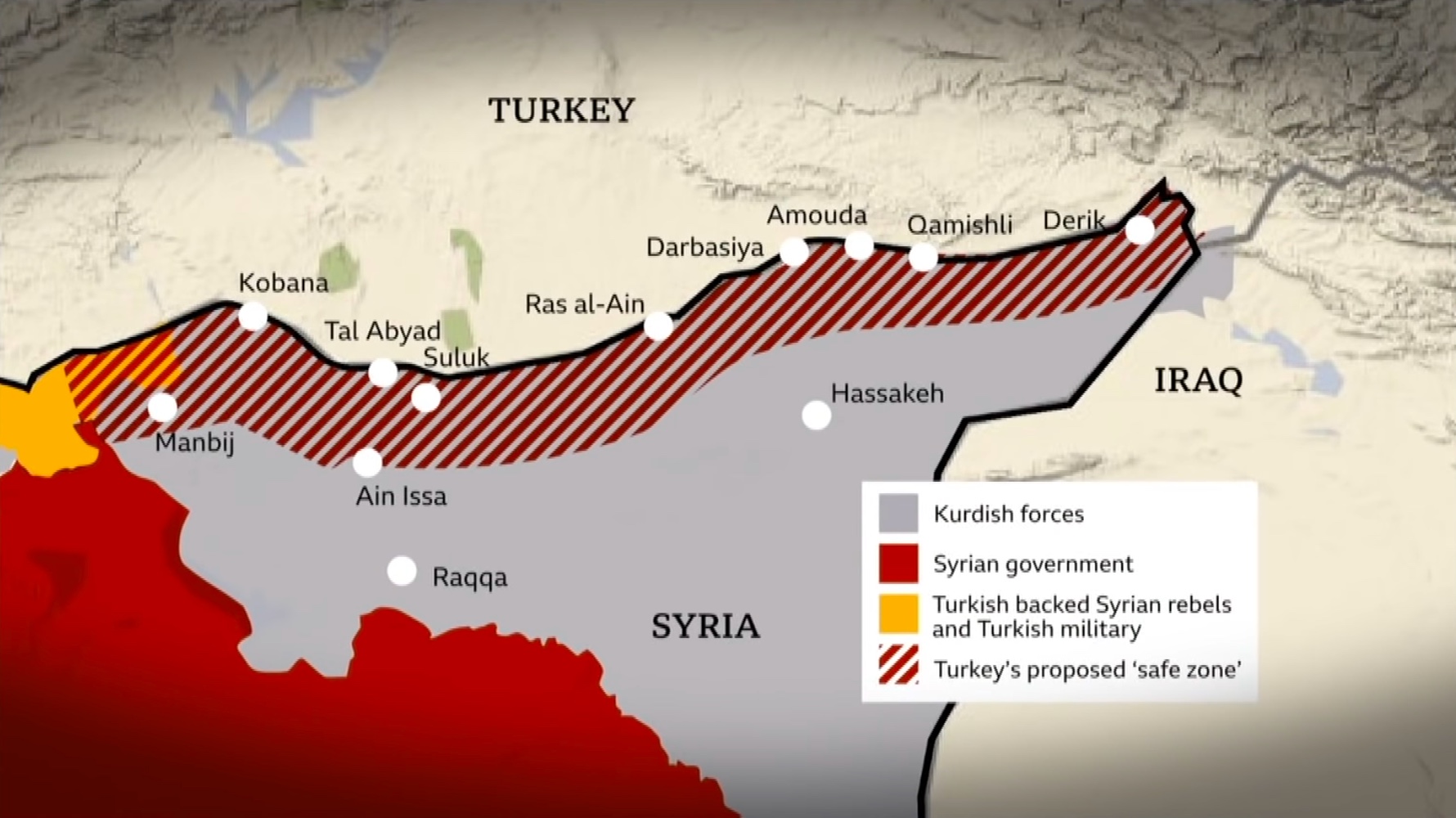

People running for cover from mortar fire on the border with Turkey, October 10, 2019. Photo: AP

Above: Syrians flee shelling by Turkish forces in Ras al Ayn, northeast Syria, October 9, 2019.

Below: Syrians bury Syrian Democratic Forces fighters killed fighting Turkish forces in the Syrian town of Qamishli, October 12, 2019.

Photos: AP

Above: On March 16, 1988, the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein launched a poison gas attack against the Kurdish town of Halabja in the final days of the Iran-Iraq War, killing some 5,000 civilians.

Below: Kurds flee the attempted Anfal genocide which killed between 50,000 and 182,000 Kurds in Iraq, 1986-1989. Photo: Wikipedia.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: