Case #9: The 1919 Massacre of Black Sharecroppers in Elaine, Arkansas

| revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIME

On the night of September 30, 1919, 100 or so Black sharecroppers crowded into a small church in Phillips County, Arkansas, three miles outside the town of Elaine. They were meeting with a white attorney from Little Rock to explore legal means of preventing white plantation owners from forcing them to sell their crops to the owners at below-market rates and to buy food and other supplies at price-gouging plantation-run stores, creating a cycle of constant debt. But this meeting soon became the flash point for one of the bloodiest massacres of Black people in U.S. history.

About six months before the meeting, the sharecroppers had joined the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America, formed in 1918 by a Black tenant farmer and WW1 army veteran. Black veterans formed the backbone of the union and many of them were at the September 30 meeting. They returned from the war militant and ready to fight for the rights they were told they had been fighting for in Europe, refusing to accept the inequalities, injustices, and brutality of a white supremacist society.

The whites of Elaine panicked when they heard Black sharecroppers were joining a union. They formed a local chapter of the American Legion and stored arms and ammunition in the local courthouse. By the night of September 30, tensions were at a boil. Fearing an attack, the Black union members at the church stationed armed guards outside. At about 11 pm, three white men emerged from the darkness, shining a flashlight on the church. One of them asked the guards, “Going coon hunting, boys?” A gunfight broke out. Who fired first is unclear, but when the gunfire stopped, one of the white men lay dead, another had been wounded. The third fled back to Elaine, reporting on the shooting. A local sheriff called on white people to “hunt Mr. Nigger in his lair.” By the next morning, mobs of armed white men, numbering in the hundreds, perhaps as many as a thousand, and some from as far away as Mississippi and Tennessee, had poured into the county. What ensued was a massive massacre, continuing for three days.

By the end of the first day, the mobs had murdered many Black people. They cut off the ears and toes of some of the dead and dragged their bodies through the streets of Elaine. On October 2, about 600 all-white federal troops arrived in Phillips County, ostensibly to stop the bloodshed. They did anything but. Many of the Black people from Elaine and the surrounding area had fled into the nearby woods, where the troops were given orders “to shoot everything that showed up.” One of the troops bragged that they “were shooting them down like rabbits.” The troops interrogated a captured Black man, found him to be “extremely insolent,” poured gasoline on him, set him on fire and, for good measure, shot him numerous times. Meanwhile, the mobs continued to hunt down Black people, killing many in the countryside around Elaine. The killing was indiscriminate—men, women, and children were all slaughtered. Five whites were also killed amidst the violence as some of the attacked Black people fought back.

By massacre’s end, more than 200 Black people were dead; some historians and others estimate the number as considerably higher. Many bodies were left to rot in the Mississippi River or cane fields.

After the massacre, nearly 300 Black people were arrested, with 122 charged by a Phillips County grand jury for crimes related to the “race riots.” Not a single white was arrested or prosecuted, but 12 Black union members were charged with first-degree murder and sentenced to death, held accountable for the five whites who had been killed. “The 12 men accused of leading the ‘conspiracy’ were tortured,” said David F. Krugler, author of 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back. “They had formaldehyde stuffed up their noses. They used electrical shocks on their genitals. They were brought to court in chains and not allowed to see an attorney. They were quickly convicted and sentenced to death within minutes.” Fearing a death sentence, 65 others who had been arrested entered plea bargains and accepted up to 21 years imprisonment for second-degree murder.

The NAACP, led by attorney Scipio Africanus Jones, and other civil rights groups intervened in the “Elaine Twelve” case, as it became known, bringing national attention to the men and helping to expose what really happened in those first few days of October 1919. In February 1923, some four years after the massacre, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the Elaine Twelve, ruling that they had been denied due process and that their sham trial had been influenced by a white mob that had gathered outside the courthouse. Eventually the men won their release, with the last of the 12 freed on January 14, 1925.

THE CRIMINALS

The racist mobs who inflicted great horror on the Black people of Elaine.

Arkansas Governor Charles Brough, who, with the approval of Secretary of War Newton Baker, called in the nearly 600 soldiers from nearby Camp Pike who joined with the mobs, local police, and other whites in the murderous attacks.

Colonel Isaac Jenks, commander of the soldiers. Years earlier, Jenks led troops in the genocidal wars against Native Americans in the West. Told by local whites that Elaine’s Black people were killing white planters and their families, Jenks ordered his soldiers to “kill any negro who refuses to surrender immediately.”

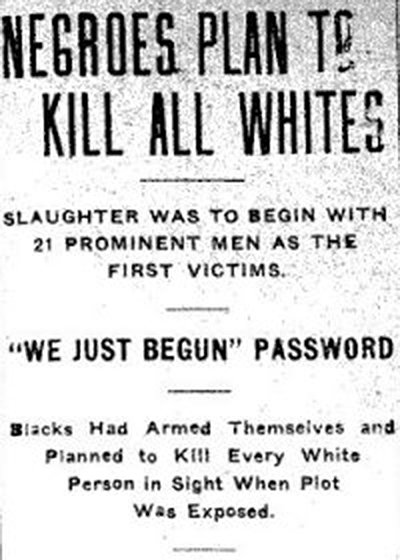

The local and national press. Even as the mobs were marauding and murdering, the Gazette, the state’s leading newspaper, blared in a headline that “NEGROES PLAN TO KILL WHITES,” and the accompanying article declared that the “Slaughter was to begin with 21 prominent white men as the first victims.” The national press was no better. On October 3, the New York Times “reported” that the “trouble [was] traced to socialist agitators.” Three days later, the Times ran a story headlined “PLANNED MASSACRE OF WHITES TODAY: Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot Among Them.”

THE ALIBI

The country was told that the Black people of Phillips County had planned a large-scale “uprising,” an “insurrection,” to overthrow the white plantation owners, take their land, and rape the women. In the days immediately following the massacre, an all-white, seven-man committee was formed to “investigate” the killings. In short order, they issued a statement in the Arkansas Democrat that the gathering at the church was engaging in a “deliberately planned insurrection of the negroes against the whites,” led by the union’s founders who used “ignorance and superstition of a race of children for monetary gains.”

THE REAL MOTIVE

With the end of World War 1 in 1918, many Black veterans of the U.S. military returned with a defiant spirit and were less willing to tolerate open Jim Crow humiliation and brutality. This was in the context of major economic, social, and political changes taking place in society—and the need that the U.S. rulers faced to maintain the brutal oppression of Black people and the whole white supremacist hierarchy on which American society was built, under new conditions.

In the South, whites were frightened by Black people’s expression of a new self-confidence and willingness to challenge the entire apparatus of vicious white planters, racist sheriffs, and the KKK. Black veterans in particular, like those who formed the backbone of the union in Phillips County, Arkansas, were seen as a major threat to Jim Crow and racial subordination. The New York Times lamented the new Black militancy: “There had been no trouble with the Negro before the war when most admitted the superiority of the white race.”

At the same time, this period witnessed the beginning of the Great Migration—thousands of Black people fled brutal Jim Crow laws and terror in the rural South to find jobs and new lives in cities of the North. But there they encountered both super-exploitation, as the lowest-paid workers in the worst jobs, and racial hostilities and pogroms, as many whites viewed them as competitors for jobs, homes, and political power.

In the year 1919 alone, in just the few months that became known as “Red Summer,” there were more than two dozen racist riots and white mob actions across the country. Hundreds of Black people were killed and thousands were injured and forced to flee their homes. In the period 1917-23, at least 97 lynchings were recorded, thousands of Black people were killed, and thousands of Black-owned homes and businesses were burned to the ground. The massacres occurred in large cities both south and north, including Washington, DC; Chicago, Illinois; Omaha, Nebraska; Charleston, South Carolina; Houston, Texas; and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Nor should we forget the hundreds murdered in the small town of Elaine, Arkansas.

SOURCES

1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back, David F. Krugler, Cambridge University Press, 2014.

On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice That Remade a Nation, Robert Whitaker, Broadway Books, 2009.

The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819-1919, Guy Lancaster (ed.), Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 2018.

“The Ghosts of Elaine, Arkansas, 1919,” Jerome Karabel, New York Review of Books, September 30, 2019.

“The Massacre of Black Sharecroppers That Led the Supreme Court to Curb the Racial Disparities of the Justice System,” Francine Uenuma, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2, 2018.

“Remembering ‘Red Summer,’ when white mobs massacred Blacks from Tulsa to D.C.,” Deneen L. Brown, National Geographic, June 19, 2020.

“Overview: The Elaine Race Massacre, Red Summer in Arkansas,” Dr. Brian Mitchell, UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture, 2019.

“Elaine, Arkansas Riot (1919),” Weston W. Cooper, BLACKPAST, September 30, 2018.

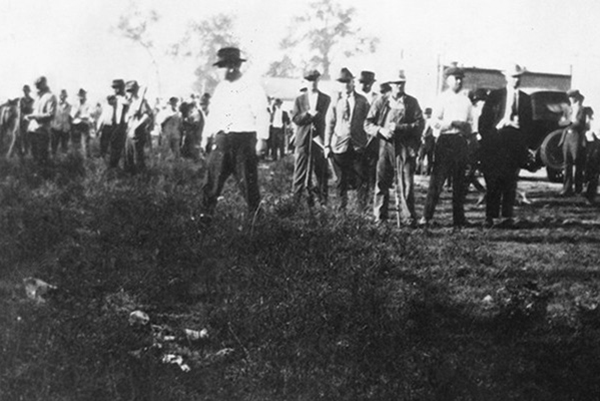

The whites of Elaine panicked when they heard Black sharecroppers were joining a union. They formed a local chapter of the American Legion and stored arms and ammunition in the local courthouse. Here a posse of whites gather on September 30. Photo: Arkansas State Archives

The whites of Elaine panicked when they heard Black sharecroppers were joining a union. They formed a local chapter of the American Legion and stored arms and ammunition in the local courthouse. Here a posse of whites gather on September 30. Photo: Arkansas State Archives

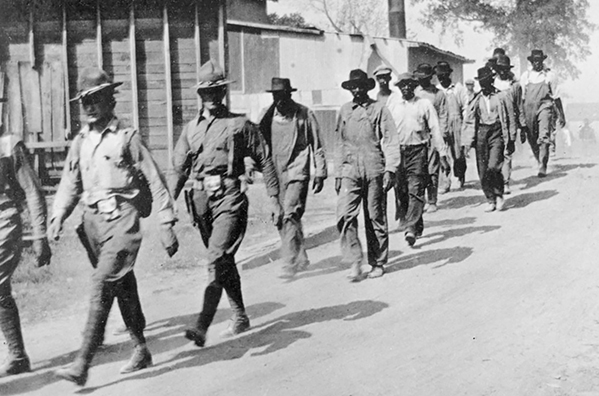

By massacre’s end, more than 200 Black people were dead. After the massacre, nearly 300 Black people were arrested, with 122 charged by a Phillips County grand jury for crimes related to the “race riots.” Not a single white was arrested or prosecuted. Photo: Arkansas State Archives

By massacre’s end, more than 200 Black people were dead. After the massacre, nearly 300 Black people were arrested, with 122 charged by a Phillips County grand jury for crimes related to the “race riots.” Not a single white was arrested or prosecuted. Photo: Arkansas State Archives

Inflammatory ad that appeared in the local newspapers.

Inflammatory ad that appeared in the local newspapers.

Among the real criminals responsible for this massacre, Arkansas Governor Charles Brough (shown here speaking to the whites of Elaine) called in the nearly 600 soldiers from nearby Camp Pike, who joined with the mobs, local police, and other whites in the murderous attacks.

Among the real criminals responsible for this massacre, Arkansas Governor Charles Brough (shown here speaking to the whites of Elaine) called in the nearly 600 soldiers from nearby Camp Pike, who joined with the mobs, local police, and other whites in the murderous attacks.

Order Communism and Jeffersonian Democracy from RCP Publications here

Listen to the podcast:

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: