Interview with a Vietnam War Vet:

50 Years Ago: Anti-war Vets Rock the U.S. Capital and the Whole Country with Dewey Canyon III Protests

| revcom.us

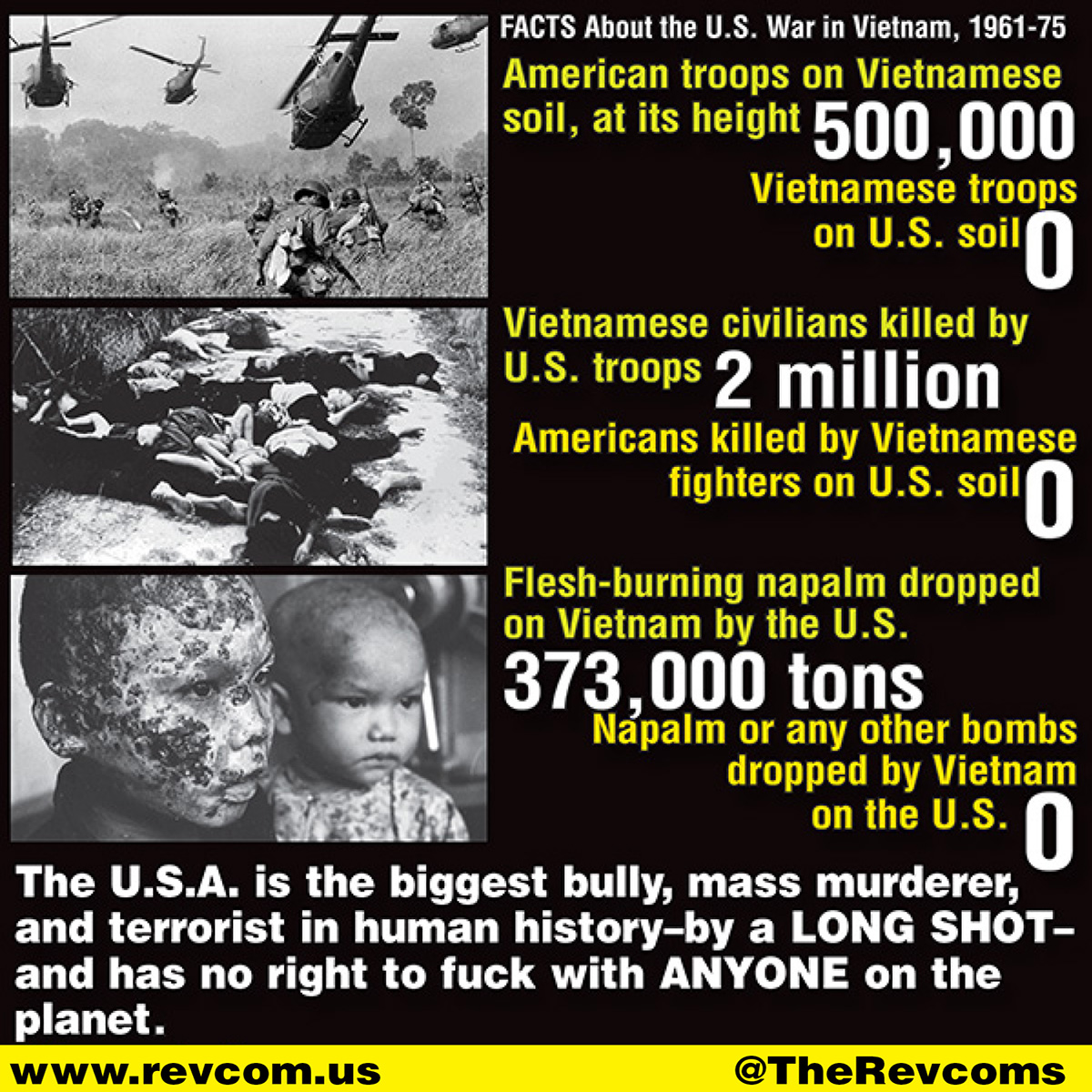

Editors’ Note: This April 19-23 marked the 50th anniversary of the Dewey Canyon III protests in Washington, D.C., led by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. The war in Vietnam is part of a whole bloody history of U.S. wars, invasions, and aggression against countries and people fighting for their liberation. The heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people, combined with upsurge of opposition within the U.S., led to the defeat of the U.S. imperialists in Vietnam. Revcom.us interviewed a Vietnam War vet who took part in Dewey Canyon III.

Q: You were part of Dewey Canyon III, the important protest by vets that happened 50 years ago against the U.S. war in Vietnam. Tell us what this protest was about and what happened.

A: I think it would be helpful if we set the stage a little bit about the period of time this was in. This was 1971. By this time, the U.S. was stuck deep in Vietnam. The Vietnamese people were waging this incredible war to drive out the U.S. invaders. And there was an anti-war movement back here in the States, and that anti-war movement had actually leaped into the military—in the sense that there was increasing GI resistance, so that by 1971 there was an article in the Armed Forces Journal by a Colonel Heinl in which he described rebellion in the ranks, drug use, fragging (killing their officers), refusing to fight... It was a very sharp article that showed GIs in Vietnam, on many different levels, refusing to fight and carry out orders. So this was the context in which Dewey Canyon III was happening.

The previous few months before this the U.S. military had put on trial Lt. Calley for war crimes, for the massacre at My Lai village in Vietnam. And they were trying to make it look like it was an “isolated” incident. The Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) had conducted what was called the Winter Soldier Investigation where 125 veterans testified, along with a whole bunch of other people, for three days about the massive horrors that the United States was inflicting on Vietnam, including very powerful testimony by veterans about the crimes they carried out against the Vietnamese people as part of the U.S. military. So that was one of the things that the VVAW did to “bring the war home” to the American people and call on the people that it was their responsibility to stop it. That was the purpose of the Winter Soldier Investigation.

And that was also the purpose of the demonstration that was scheduled April 19 to 23 in Washington, DC. It was called Dewey Canyon III, because there had been two previous U.S. military operations—called Dewey Canyon I and Dewey Canyon II. Dewey Canyon II was actually an invasion of Laos—American soldiers had gone into Laos along with a horrific air war that was being carried out in Laos. So we called it Dewey Canyon III—an “incursion into the country of Congress.” “Incursion” was the language the military was using about their invasion of Laos.

The idea for this protest was first proposed at a national coordinators meeting of the VVAW, where John Kerry (who would later become a U.S. senator) put forward the idea of going to DC to carry out a demonstration. His idea was that this was going to be to lobby Congress. And it turned into a bigger deal.

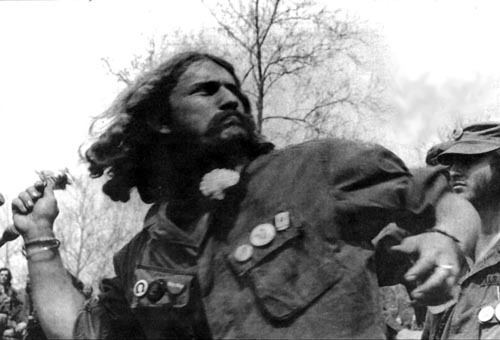

The idea was that we were going to DC and camp out on the Mall. We ended up staying there for five days, from Monday through Friday. We spent the week going throughout the city and carrying out guerrilla theatre operations where we dressed up in our fatigues and, along with theater people and artists who pretended to be the Vietnamese, and we would do re-enactments of the crimes that we had carried out in Vietnam. This was not the first time we had done this. We had done this previously in the fall of 1970. We had carried out a 77 mile march from Morristown, New Jersey, to Valley Forge, and we did similar guerrilla theater for the length of those 77 miles. So we had it down pat about how to these kinds of things.

The week involved something like 1,000 vets, and people came from all over. We were going all over the city, doing different kinds of things, and lots of people were getting arrested, including dozens at the Supreme Court. There were a couple of days when the lobbying on Congress went on. One of the things that happened as we were going around DC was that we passed a group of Daughters of the American Revolution, a right-wing group, and this woman said to us, “What are you doing? You’re going to upset the troops.” And we responded, “Lady, we are the troops!”

In camping out at the Mall for the week we had to have security at night. We had to be aware of people coming into the camp and disrupting, both innocent people who were drunk or whatever, but more importantly, we knew that the government didn’t want us there. So I was walking around one night on security and came upon three or four guys with very short hair. Young as I was, or even younger. I got into a conversation with them, and asked them, “Why are you guys here?” One guy said, “Well, we’re here to support this.” We talked further, and finally he said, “You know, we’re on alert to put you down.” I said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “We’re from Fort Bragg.” I asked what was going to happen. And he said, “Don’t worry, all the vehicles have been sanded. Nothing will run.” The hair on the back of my neck shot up.

Q: These were National Guard or regular military?

A: They were Army soldiers. Years later I would come to find out the Marines at Quantico (a base in Virginia) were also on alert to possibly put us down. But this was an example of how profound the GI movement was seeping into the military worldwide—not only with the GI newspapers on every U.S. military installation in the world, but there were rebellions among troops in Germany who were refusing to go to Vietnam, and many other examples. This massive GI resistance was growing. I had been deeply involved in the vets movement, but this was one of the first times I realized there’s something bigger going on here than just these veterans I’ve been organizing. The government was also trying to mobilize the DC police against us, and there was disagreement among the ranks, and they were not able to mobilize the police to come after us. Years afterward, I watched a 2013 film called Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight, and in there is the story of the struggle in the Supreme Court around how they’re going to decide the Ali case, of his refusal to go to Vietnam. There’s a discussion in there where two Supreme Court justices are going back and forth on this, and one of them makes a comment about the veterans that are there right on the Mall outside the door. This was part of the stage that Dewey Canyon III was happening on, right when there was tremendous struggle among the rulers around how they were going to handle the war and the resistance. Also, the DC government filed a suit with the Supreme Court to try to force us to leave the Mall. We veterans held a vote—it was a close vote, but we voted to refuse the order to leave. The next day, New York Daily News had a headline, “Veterans Overrule Supreme Court.”

Q: A big part of Dewey Canyon III was the vets throwing their medals at the Capitol.

A: The plan had been that at the end of the week, we were going to go somewhere near the Capitol, where we were going to carry body bags with stage blood in the body bags, and we would take our medals and throw them at the bags. It was symbolic, and very passive. When we came to DC we thought we were going to tell the Senators things they did not know about what the U.S. was doing in Vietnam, and that if we just told them the truth, that would help to reverse the war. It was a very profound experience that we summed up that these Senators knew exactly what was going on and that they didn’t care, and they didn’t want us veterans there. So by the end of the week that body bag idea was dumped, and it was decided to take our medals and throw them back at these mf’ers.

As the veterans lined up at the Capitol, the government had constructed a fence. We hung the word “trash” on it. And somewhere around 600 to 800 veterans lined up—it went on for several hours—to throw their medals away, over the fence toward Congress. As vets hurled their medals they made various statements. One was, “We don’t want to fight again, but if we have to it’ll be to take these steps.” Another one was, “I got a Purple Heart. I hope I get another one fighting these motherfuckers.” VVAW was sort of a coalition between two kinds of vets. The leadership and the majority of the membership was coming at this from wanting to oppose the crimes we had committed against the Vietnamese people and to expose the truth about those crimes. But there was another section of vets who wanted the war to end mainly because Americans were dying. And that was reflected in some of what was said at the medal throwing. But mainly it was people like this Black vet who said, “I apologize to the non-white people of the world for what the United States is doing to their countries.” Other people got up and said about their medals, “Here’s a bunch of shit.” This went on for hours and hours. You can watch some of the footage on YouTube.

This broke through the U.S. media in a way that nothing before had done. We were the first story on CBS, NBC, and ABC national network news, every night of that week—covering the different things we were doing, showing the guerrilla theater, throwing of the medals, etc. The actions of VVAW changed the image of the veteran in this country from one of the patriotic WW2 type to what people saw at Dewey Canyon III—anti-war, angry, and for many—unpatriotic. I think it is important to stress how there were these veterans of the U.S. military siding with the humanity (and, for many of us, the victory) of the Vietnamese people, especially now as the white supremacy and xenophobia of ex-military fascists are much in the news.

GIs refuse to return to combat, AK Valley, Vietnam, September 1969.

Dewey Canyon III, April 1971

On April 23, as part of Dewey Canyon III, 800 to 1,000 vets lined up outside the Capitol to walk up the Capitol steps and throw their medals back at the U.S. Congress and the rulers of America. Some of the comments from the vets as they threw their medals over a fence marked “trash” were: a Black vet who said, “This is my opposition for the policies of this country against the non-white peoples of the world”; “My name is Peter, I got a purple heart here and I hope I get another one fighting these motherfuckers”; “We don’t want to fight again, but if we have to it’ll be to take these steps.”

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: