Bitter Harvest

How the system ruined Black farmers

| revcom.us

"The root of racism in America is on the farm. It started on the plantations with slavery."

Tim Pigford, Black farmer

in Wilmington, North Carolina

"African Americans know that, far from getting help from the Government in a time of need, it was often Government officials who terrorized them and their families. While millions of government dollars have been made available to white Americans, their Black neighbors often couldn't even use the court system to sue a white person who owed them money, stole from them or even killed their family members."

Letter to the New York Times about

the plight of Black farmers

After the Civil War, Reconstruction promised former slaves forty acres and a mule. But this was a promise quickly denied. General Sherman set aside thousands of acres of confiscated and abandoned land in Georgia and South Carolina for settlement by Blacks. But this offer was soon canceled by President Andrew Johnson, who returned the property to its prewar owners.

Most Black people who have acquired land since the Civil War have either inherited it or bought it. And it's been a huge battle for every generation of Black farmers, just to keep the land. Black farmers have faced racist local officials and greedy white farmers waiting to grab up their land. They've faced murderous KKKers who have burned down their farm houses. And they've faced government officials who've systematically sabotaged their efforts to work the land.

Today affirmative action programs are being attacked and dismantled with the argument that "discrimination is a thing of the past." But this is a lie. And the story of how the U.S. government has helped to destroy Black farmers is a particularly sharp and bitter example of how Black people in this country continue to face systematic and institutionalized racism.

A recent class action law suit filed in 1997 against the government has brought to light how, for decades, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has had a systematic and racist policy toward Black farmers—unfairly denying or delaying loans and other benefits.

On January 4, 1999 the USDA settled the suit before going to trial. Under the terms of the settlement, the USDA may end up paying as much as $300 million and possibly more for claims dating back 16 years. But this settlement is only a drop in the bucket in the face of the tremendous hardship and financial loss suffered by thousands of Black farmers. The government is offering individual farmers up to $50,000 and cancellation of their loans. But these farmers, after years of discrimination, face all kinds of other bank and commercial loans. In some cases, they were forced to file for bankruptcy. Farms that had been in the family for generations were lost. And many lives were ruined.

The Destruction of Black Farmers

"If I can't get any loans, there will soon be one less Black farmer. The nail is being driven further in the coffin every day.... We'd be better off if we were eagles or snails. There's more interest in saving endangered animals than saving the Black farmer."

Lucious Abrams, whose family has been farming

in Georgia for four generations"The facts of life are that all small farmers are disappearing. But it just seems that on the way out it's the Black farmer who is really catching it."

Albert J. Perry, Black farmer in Alabama

Over the years, small farms in the U.S. have been crushed by corporate agribusiness, which is the most profitable industrial sector in the country. During the 1980s low farm prices and high production costs forced 24 percent of the U.S. rural population off the land. Four million farmers have been eliminated since 1945. And Black farmers—many who can trace their family's history back to farms owned by great-grandfathers who were former slaves—have been hit the hardest.

Over 100 years ago, when the first annual Farmers Conference for Blacks was convened at the Tuskegee Institute, it was barely a generation after the end of slavery and about 60 percent of all employed Blacks in the United States worked on farms. In 1920, 14 percent of the nation's farms were owned by African Americans. But by 1992 the number of Black farmers had gone down to around 19,000—only one percent of the country's two million farmers. Black farmers have been losing land at the rate of at least 1,000 acres per day—a rate three times the national average.

Black farms are generally small—the average, 50 to 100 acres. They mostly cultivate vegetables and some grow cotton, peanuts and tobacco. Nearly 95 percent of Black farms are located in the Southeast, with a few scattered throughout Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri. Seeing the hardships of their parents, most children of Black farmers are leaving for other jobs. The average age of Black farmers in the U.S. is now 70.

In the mid-1970s low-interest federal loans were readily available. Encouraged by agriculture officials, Albert J. Perry, like many other Black farmers, took out a loan to expand his crops, buy equipment and get into livestock. The next year the bottom fell out of the soybean market. A year later, hurricanes destroyed much of the crops, and the next year there was a drought. Perry had three bad years out of five and almost went under. He held on to his land but lost much of the new equipment that had been the collateral for the loans. He said, "White farmers in the area had the same problems I had, but the system just seemed more forgiving of them."

Perry told of one Black farmer in the area who was in his 60s and had borrowed heavily to increase his peanut acreage and buy a used combine. He was harvesting a crop that would have brought in $20,000 when the combine broke down. The repair bill was $200, but local officials of the Farmers Home Loan Administration wouldn't advance him the money for repairs. The farmer lost his crop, defaulted on his loan and lost his land. A year later he had a stroke.

Another Black farmer, Robert Coleman, was able to keep his farm only because he also had a job as an equipment operator at a nearby mine. In 1992 he told the New York Times, "Most of the money in agriculture goes to the big farms, not the small farmers, and it's twice as hard for the Black farmer. Some of us lose our land in a bad year or through bad management. Some of us don't have the best land in the first place and we can't afford the new techniques that produce higher yields. As for me, I'd have lost my farm if it wasn't for the job at the mine."

Loans are granted to farmers, based usually on their next crop, to cover their large operating expenses. If farmers can't get the capital necessary to sow their crops, they face financial ruin. For those who can't get private credit, the USDA is the lender of last resort. And with the tradition of Jim Crow in the South, Black farmers have historically been shut out of private loan markets and so are heavily dependent on USDA loans. But the USDA has disproportionately denied Black farmers loans. A 1983 USDA task-force report found that local USDA officials were "rude and insensitive to Black farmers," calculated Black farmers' projected crop yields differently from those of white farmers, and often rejected Blacks for loans based on "computation errors."

In 1984 and 1985, the USDA loaned $1.3 billion to farmers nationwide to buy land. Of the approximately 16,000 who received those funds, only 209 were Black farmers. A report by the research organization Environmental Working Group found that between 1985 and 1994, the average Black farmer received less than a third of the amount in federal subsidies that the average white farmer received.

According to John W. Boyd, head of the National Black Farmers Association, the USDA provides loans to white farmers at lower interest rates than to Blacks, grants loans to Blacks later in the crop season than to whites, and often shelves Black farmers' loan applications all together. He says local USDA officials have even altered some Black farmers' loan requests to increase their likelihood of being rejected and accelerated others' repayment schedules without explanation.

Evidence shows that the average white farmer's application takes about 60 days to process, while a Black farmer's application—if it is processed at all—takes more than 120 days. This and other racist government policies have directly caused foreclosures and the continued loss of Black farms.

Black farmers say they have been routinely denied the assistance granted almost automatically to white farmers and that federal officials sometimes demanded evidence of agricultural and financial expertise that was not required of white farmers, or delayed processing loans until after the planting season. Sometimes Black farmers had their applications rejected, accompanied with overt racist remarks.

Black Farmers vs. the USDA

"I tried for nine years to get a farm operating loan. Back in 1992 the county supervisor for the department threw my application in the trash. He said they didn't have any more money. When the investigator asked him why he had made only two Black farm loans, he said Black farmers were lazy."

John W. Boyd, a tobacco farmer

in southern Virginia and head of the

National Association of Black Farmers

The National Black Farmers Association represents about 60,000 farmers and their family and other supporters. At a protest to demand the UN Commission on Human Rights take up their case, they pointed out that the way the government deals with Black farmers is a human rights violation—and a continuation of the racist way Black people have been treated since slavery.

In 1997, the National Black Farmers Association, representing nearly 1,000 Black farmers, sued the USDA in a nationwide $2.5 billion class action suit. Lawyers for the Black farmers clearly documented USDA discrimination against Black farmers. And the suit also exposed how the USDA simply ignored hundreds of complaints filed by Black farmers and how this was particularly true in the 1980s—when the Reagan administration dismantled the Agriculture Department's civil rights office, leaving hundreds of discrimination complaints to gather dust or end up in the trash.

For many years, the USDA had denied any discrimination took place. But by the time the Black farmers' filed their lawsuit, the USDA had been forced to admit that the agency has discriminated against Black farmers. One report by the USDA's own civil rights action team admitted, "Minority farmers have lost significant amounts of land and potential farm income as a result of discrimination." And the USDA had to admit that they had simply ignored hundreds of discrimination cases filed by Black farmers. Some of the Black farmers who joined the class action suit have been fighting for justice and redress for 15 or 20 years.

In April of 1998, the Clinton administration imposed a new bureaucratic blockade against the Black farmers' suit. Turning right and wrong upside down, government officials claimed that many of the Black farmers' claims were so old that the "statute of limitations" had run out on them—that a two-year time limit barred them from getting any restitution. The Clinton administration wanted to deal with the Black farmers' claims on a case-by-case basis—which would not only delay justice the farmers were due but deny them the right to appeal any rejections. These plans to enforce the two-year statute of limitations was a particularly vicious slap in the face, given the fact that after Reagan abolished the USDA's Office of Civil Rights, Black farmers didn't even have any way to lodge official complaints. And it wasn't until 1996 that the Clinton administration restored the Office of Civil Rights in the USDA.

At the end of 1997, President Clinton met with John W. Boyd and several other leaders of the National Black Farmers Association and promised to seek a resolution of the case. Congress eventually passed a bill that extended the statute of limitations in the case beyond the usual two years. But meanwhile, for another year, no real settlement materialized.

Black farmers held large protests in Washington, DC—at one point they tied a mule to the White House fence—making a link with the fact that Blacks had been promised, but had never gotten, their "forty acres and a mule" after the Civil War.

When the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Dan Glickman, spoke before the NAACP's annual convention, Black farmers held a protest march outside. Inside, Glickman admitted in his speech, "I spent nearly two decades in Congress. In all that time, I can recall only once the issue of minority farmers being raised. There was not one hearing in the House or the Senate in modern times until this issue blew up." He also revealed, "In the 1990 farm bill, Congress authorized $10 million annually to provide technical and resource assistance to minority farmers through Black land-grant colleges and other community organizations—the same kind of assistance white farmers customarily get through USDA extension offices. The trouble is, Congress never followed up in the appropriation process. Only $13 million has been allocated to the minority farmers' rights program since its inception, not the $60 million its authors anticipated."

Bitter Harvest

In May 1998 a federal judge urged the Clinton administration to settle the Black farmers' lawsuit against the USDA in order to avoid a costly, time-consuming trial. By the end of the year it looked like the government wanted to settle to avoid going to trial—scheduled to start February 1, 1999. On January 4, the USDA announced they had settled the suit. The department's civil rights director, Rosalind Gray, said the department would not admit to having discriminated against the farmers—but would agree that its procedures in handling bias claims had been "flawed."

According to the terms of the settlement, Black farmers who have an active discrimination case or who file an affidavit of discrimination naming specific officials who denied them loans will be eligible for $50,000 tax-free and will have all their government debts forgiven. The average debt for most Black farmers is $75,000 to $150,000.

The settlement says Black farmers who have better documentation of discrimination can forego the $50,000 award and negotiate higher awards with an outside arbitrator. John W. Boyd says up to 2,000 Black farmers could file claims as part of the settlement and that the majority will likely claim the $50,000 award because they lack the explicit proof of discrimination necessary to fight for a larger award.

This settlement hardly even begins to compensate Black farmers for all they've lost and doesn't punish any of the USDA officials who presided over decades of injustice toward Black farmers. Among many Black farmers this settlement leaves a bitter taste.

Willie E. Adams, a fourth generation Black farmer, is raising 48,000 chickens on the same land in Atlanta that his ancestors farmed. But with debts of $150,000— $90,000 to the federal government and $60,000 to banks—he says, "I'm just keeping my head above water." By his calculations, he could be raising more than twice as many chickens if the USDA had fairly processed all the loan applications he's filed over the last 22 years. Turned down by the USDA, he had to get higher-interest commercial loans. But unable to carry a lot of debt on these terms, he hasn't been able to modernize his feeding and watering equipment to meet the standards of today's poultry processors. So three of his five chicken houses, each longer than a football field, have stood empty for more than three years.

Many Black farmers say getting $50,000 and having their federal debt written off is too little and too late—particularly for those who have lost their farms to foreclosure or who were forced to declare bankruptcy. And like Willie Adams, they point out that the settlement won't help them with all the commercial debt (at higher interest rates) they had to take on when they couldn't get loans from the government.

Charles Dennard, 47, a Black farmer who grows cotton, peanuts, soybeans and watermelon on 90 acres in Pineview, Georgia, told the New York Times, "As far as the settlement, it's not going to be of help to me. If all your debt is with the USDA, it'd be a great help. But I'm tied up with debt to the bank and the USDA." Dennard owes the government $72,000, which should be forgiven under the settlement. But he still owes another $88,000 to private lenders—from loans, he points out, he would never have applied for if he had been treated fairly by the USDA.

John DeCourdreaux, a blueberry farmer from South Haven, Michigan, also says he's not satisfied with the settlement. "To me, this is a pat on the back from the Agriculture Department, saying, `We acknowledge what we did. Here's enough money to get out of our hair.' Well, I don't want a pat on the back and it's not enough money." DeCourdreaux points out that he was denied hundreds of thousands of dollars in USDA loans and now, $50,000 won't even buy him a good truck.

Gary R. Grant is president of the Black Farmers and Agriculturists Association and a plaintiff in the lawsuit. His family grows peanuts, cotton, corn and soybeans on 250 acres in Tillery, North Carolina. Grant says the settlement is "neither moral nor just" in that it doesn't punish any federal officials who denied Black farmers loans, crop subsidies and other benefits. He said, "These folks took our homes, took our credit rating, took our man and womanhood and personhood. These folks are not even getting slapped on the wrist as far as we know."

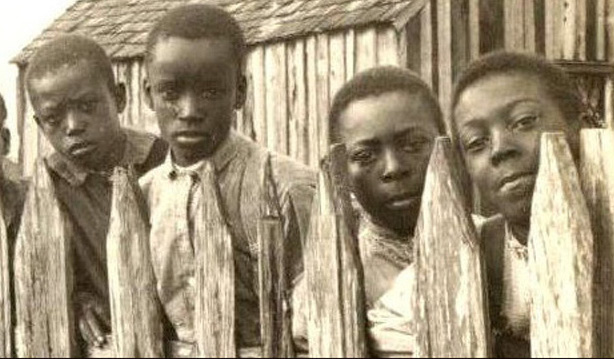

Black farmers have faced a long history of racist local officials and greedy white farmers waiting to grab up their land. They've faced murderous KKKers who have burned down their farm houses. And they've faced government officials who've systematically sabotaged their efforts to work the land. Above: a Black farmer in Alachua County, Florida, 1913.

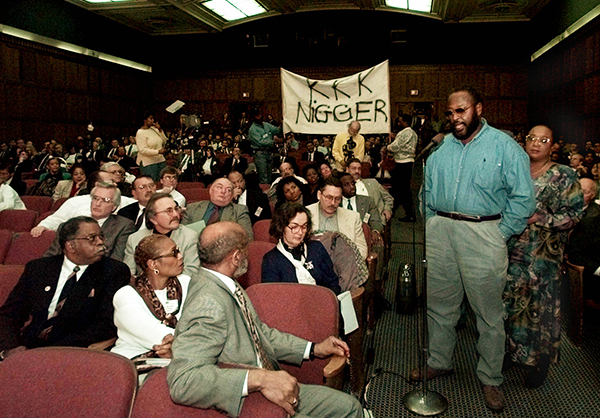

Robert Williams Jr., a farmer from Nolan County, Texas, and his wife La-Verne arrive for the Civil Rights Listening Session at the Agriculture Department in Washington, January 22, 1997. The session was held to discuss the Agriculture Department's civil rights record. A participant holds a banner similiar to the one found on Williams' farm in 1994. (AP Photo/Brian Diggs)

See also:

As Judge Blocks Law to Redress Discrimination Against Black Farmers...

You Need to Know This History

Acres of Injustice

The Lives of Black Farmers

John W. Boyd, Jr., from Baskerville, Va., founder and president of the National Black Farmers Association, speaks during a rally in front of the United States Department of Agriculture with his mule in the foreground in Washington, April 28, 2009. The group is rallying in support of a bill for government funding of compensation for Black farmers, who were discriminated against. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: