Acres of Injustice

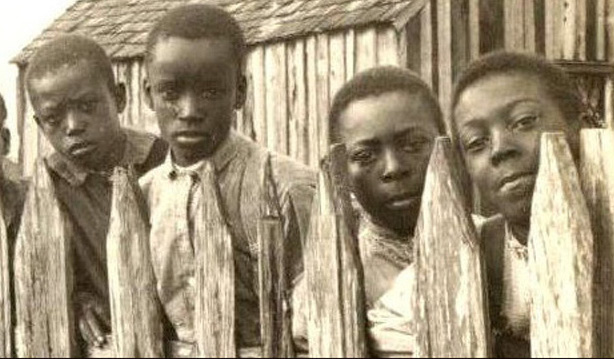

The Lives of Black Farmers

| revcom.us

When Lloyd Shaffer applied for an equipment loan from the USDA, a county official denied his application and told him: "All you need is a mule and a plow."

When George Hall applied for crop-disaster relief from the USDA, a county loan officer referred to the Black community as a "baby factory," and called Black people "generally irresponsible" and unable to handle financial matters.

When Abraham Carpenter applied for disaster relief, a county official decided his request was, "too much money for a n*gger to receive."

A May 1, 1998 Wall Street Journal article by Roger Thurow profiled some of the Black farmers involved in the 1997 discrimination suit against the U.S. government. These men experienced blatant racism from United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials. And they also encountered more subtle ways that the government agency sabotaged their efforts to farm the land. A systematic practice of discrimination against Black farmers emerges: Loans denied outright. Loans delayed until the end of the planting season. Only a small amount of a loan request approved. Denial of crop-disaster payments.

*****

Eddie Ross' grandfather was a sharecropper. His father also farmed land in Mississippi and owned a small plot. Eddie Ross learned farming from his grandfather and father and in 1986, when he was 23 years old, he started working for a white farmer, planting 1,000 acres. He also started renting out land for himself. First 47 acres, then five years later, another 775 acres near the Mississippi River. He had a plan to grow cotton and soybeans and applied for an operating loan from the Warren County USDA office.

Eddie Ross waited a long time to hear from the county lending committee. White farmers his age in the area were getting loans. And Eddie was an experienced farmer. He had been working larger pieces of land than what was in his proposal to the USDA. But they rejected his application outright, for "inadequate management ability/experience for scope of planned operation."

Eddie appealed the loan decision and also filed a civil rights complaint. A national USDA appeals review found that Eddie Ross had in fact been discriminated against and approved his loan. But by the time all this went through and Eddie got his money it was already mid-June. The cotton-planting season was gone and it was too late for soybeans. But Eddie planted anyway. Then in the fall, bad weather hit the crops and there was no way Eddie could pay back the loan. As Eddie put it, "I was already behind and I hadn't even started."

The same thing happened every year for the next few years. Eddie would apply for a loan. It would get delayed, then approved real late in the season. Eddie would be forced to plant late, resulting in bad crop yields. Each year debt piled up. And each year Eddie filed another discrimination suit.

In 1997, the USDA finally looked at Eddie Ross' complaint. They admitted that Eddie Ross had been subject to racial discrimination on a continuing basis. And they also reported that each year, the discrimination got worse as county officials retaliated because of Eddie Ross' suits. For example, in 1993, a county supervisor delayed processing Eddie's loan application until after county officials went through the civil rights "sensitivity training" that had been ordered after Ross' earlier complaints!

The USDA was supposed to give Eddie Ross a cash settlement close to $500,000. But right before he was supposed to get the money, the USDA stopped payment because they were worried that the settlement could hurt its position in the 1997 class action suit being brought against the USDA.

In December 1997, Eddie Ross went with other Black farmers to meet with Bill Clinton at the White House. Ross asked Clinton, "Where's my money?" In January Eddie Ross received a piece a mail with a Washington, DC postmark. He thought it was his money. But when he opened up the envelope he found a form from the Internal Revenue Service, saying how much tax he owed—on the settlement he had never received!

Eddie Ross finally did get some money from the USDA, but only a fraction of the amount he had originally been awarded. The USDA said they would compensate Eddie for only a couple of years of discrimination, and that if Eddie wanted compensation for the other years, he would have to pursue it in the federal suit.

*****

In the late 1980s, Lloyd Shaffer was the local leader of the NAACP in Yazoo County, Mississippi. He led a boycott of white-owned businesses to protest poor school conditions and other problems faced by the Black community. White farmers who considered Lloyd a "troublemaker" started to snidely call him, "Mr. NAACP."

Just like Eddie Ross, Lloyd Shaffer got into farming through his father. After his parents died, when he was just a teenager, he started working a white man's land and also helped out on some of his relatives' farms.

In 1991 Lloyd Shaffer wanted to buy a 200-acre farm of his own and went to the bank for a loan. When he was turned down he went to the Farmers Home Administration, a part of the USDA. Lloyd says a county loan official there sneered at his plan: "He threw my application in the trash can, right while I was standing there...They were rude."

The next year, Lloyd Shaffer leased 243 acres and planned on planting soybeans. He applied for an operating loan and a loan to buy more equipment. Even though he didn't have enough money for proper fertilization, the crop came in pretty good. But when the loan for additional equipment didn't come through, Lloyd had to wait to harvest the crop. It was the end of the year by the time Lloyd was able to finish picking—the quality and yield of the crop had really declined. And when he added up his books, Lloyd couldn't pay off the loan.

Just like Eddie Ross, Lloyd Shaffer faced the same sabotaging cycle of discrimination every year—of late loans, low yields and rising debt. At one point, the lending agency foreclosed on Lloyd and took away his equipment right in the middle of the harvest. Lloyd's debt went over a quarter of a million dollars and he couldn't even make the annual interest payments.

*****

George Hall is a Vietnam vet, a Black farmer and the sheriff in Greene County, Alabama. When he came back from the war he began working some land owned by his family and renting out some other land as well. In 1985 he applied for an $80,000 loan in order to farm an additional 100 acres. He put up his home as collateral and the loan was approved. But then, when George Hall applied for another loan to buy some cattle to put on the land, he was rejected. He told the WSJ, "They set you up for failure. You put your house and land up to buy more land, and then they won't let you borrow more to be productive."

Unable to really utilize the land he had acquired, George had a hard time making the loan payments. In 1987, facing foreclosure, he filed for bankruptcy in order to prevent losing his house. He went back to growing vegetables, sorghum and sugar cane. He became the sheriff of Greene County, a predominantly Black county in western Alabama, but continued to farm.

In 1994, the whole state was hit with bad weather. Like other farmers throughout the county, George Hall applied for disaster benefits. But unlike most other farmers, George got some money but had another big chunk of his claim rejected. He filed a discrimination claim. It was over only about $3,000 but for George, "It was a matter of principle. They didn't want to give any more to a Black man."

USDA investigators in 1996 finally admitted they had discriminated against George Hall. County officials had claimed George was a bad farmer and didn't properly cultivate and fertilize his crops. But white farmers in the area—who also didn't cultivate or fertilize because of the wet weather—"received expeditious approval" of their disaster payments. The USDA investigation also revealed that a county officer had referred to the black community as a "baby factory" and called Black people "generally irresponsible" and unable to handle financial matters.

*****

In 1976, Tim Pigford had just gotten married. His father and grandfather had owned and worked the land. Tim wanted a farm of his own too, so he applied for a loan to buy a 175 acre farm near Wilmington, North Carolina. The USDA county lending committee approved a loan to build a house and awarded Tim an operating loan to farm some rental acreage. Things looked good. But then the ownership loan was denied. This was the beginning of a pattern that would continue for the next 22 years, where Tim Pigford would get approval of an operating loan but no ownership loan.

In 1984, Tim Pigford was invited by the U.S. Congress to testify in Washington about civil rights and farming. He told the congress he believed racism had been keeping him from getting a farm ownership loan.

Three months later, the county committee declared Tim Pigford ineligible for operating and ownership loans for the 1985 season. They claimed he lacked training and experience; one official suggested he become a teacher.

Pigford filed a discrimination complaint. He told the WSJ: "I had lived in North Carolina for 20 some years. I didn't need anyone coming up to me and calling me `nigger' to know what's going on. They didn't want a Black man owning more than 40 acres and a mule."

With no loans, Tim Pigford couldn't farm and started working odd jobs while his wife, Clara, worked as a kindergarten teacher. They had two young children and still faced the debt on the old farm operating loans. Bills piled up and, in 1986, with the electricity bill over $1,500, the power to the house was cut off. Tim Pigford and his family lived in a dark house for a year and 12 days.

In 1992 the government began foreclosure proceedings. Tim and his wife couldn't afford a lawyer and represented themselves. In the fall of 1994 they were evicted from their house. In May of 1995, on the Pigford's 20th wedding anniversary, their house was seized by federal marshals. Tim's brother bought the house at a foreclosure auction to keep it in the family and a year later Tim and his family were able to move back in. All this has taken its toll on the Pigfords—Tim's oldest son has suffered a nervous breakdown, Clara has ulcers and an irregular heartbeat, and Tim has high blood pressure.

Tim Pigford figures he has been to Washington 120 times since 1984—he calculates he's driven more than 115,000 miles, back and forth. In April 1997, the Pigfords spent a week in Washington, DC meeting with USDA officials to try and settle their complaint, but no agreement was reached. Shortly after this, Tim was fired from his job at a fiber-optics factory—for taking too many days off to work on his case.

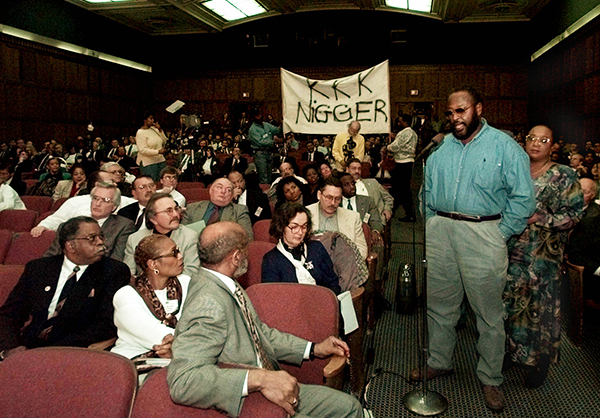

Robert Williams Jr., a farmer from Nolan County, Texas, and his wife La-Verne arrive for the Civil Rights Listening Session at the Agriculture Department in Washington, January 22, 1997. The session was held to discuss the Agriculture Department's civil rights record. A participant holds a banner similiar to the one found on Williams' farm in 1994. (AP Photo/Brian Diggs)

See also:

As Judge Blocks Law to Redress Discrimination Against Black Farmers...

You Need to Know This History

Bitter Harvest

How the system ruined Black farmers

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: