Revolution #48, May 28, 2006

Film Review: Darwin’s Nightmare

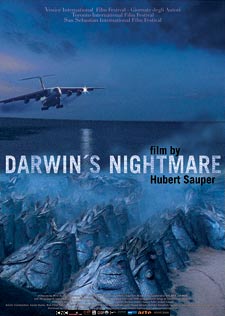

The following review of the movie “Darwin's Nightmare” is from A World to Win News Service (December 19, 2005):

19 December 2005. A World to Win News Service. The once spell-binding natural beauty of the landscape around the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania stands today in sharp contrast to the wretchedness of the inhabitants and their fly-infested, horrendous surroundings. This is part of the Great Lakes Region of Africa, said to be the origins of humanity. Today, the people live mainly on fishing and the fish processing industry all along the shores of these lakes. The documentary film Darwin’s Nightmare reveals virtually all the contradictions in and around Mwanza in scenes taking place in a fish factory, the factory manager’s office, an isolated airport, tiny leaf-thatched hovels called homes by the village folks. An international conference on ecology, a conference room for bureaucrats and visiting European Union Commission dignitaries, the compound of the National Institute of Fishery, massive former-Soviet built Ilyushin cargo planes from Russia, hotel rooms for airline pilots and plane crew members from Europe. The film brings out graphically all the horrors of utter destitution—the continuing impoverishment (half of Tanzania’s population live on less than a dollar a day) and exploitation of the country and its people under the domination of the great powers of the day—making the viewer seethe with anger.

This film brings home the many contradictions in Tanzanian society which are clearly tied into a knot… and over and over again our hearts scream out for the great need of the people to rise, rise in revolution...

We see so many children in rags, anywhere from four or five years old to ten and twelve. The playful, the silent, the timid and shy, the insolent and brazen, the aggressive and the pitifully bullied. Kids waiting impatiently, with plates and bowls in hands for rice and fried fish-head handouts, while older boys do collective cooking in the warm night air. When the cooking is done, kids scramble over every morsel of food. We see kids sniffing glue so they can fall asleep and forget that they have nowhere to live. So many children and youth with only one leg scurrying along on crutches. Children giggling, playfully wrestling, quarreling, bullying and fighting like children anywhere in the world. Very young girls sticking close to even younger boys for relative safety lest older boys attack or abuse them sexually.

We see too the spread of the tentacles of the hideous “free-market” in this desolate but rich region: cartloads of the giant Lake Victoria fish destined for the supermarkets of Europe and Japan, now heaved and shoved towards the factory. Boatmen busy repairing fishing nets and boats—all for bare survival. Youth and adults in tatters, wading, ankle-deep in muck and piles of remains of rotting fish, laid out to dry in the sun. Kids and elders alike foraging, fighting over tidbits. Maggots and worms crawling over rows and rows of fish skeletons and heads, all that’s left for sale to the common people after the succulent meat has been neatly carved out and processed for export. Frenzy of activity: factory workers hard at work. Boatmen hacking and sawing, fishermen hauling in their catch.

As deeply troubling and even revolting for anyone concerned with questions ranging from ecological disaster to the ruining of human lives as it may be, Hubert Sauper’s award-winning film (Best Documentary European Film Award, the winner of the Grand Prix du Jury Award and the Europa Label Jury Award) is a must-see. It seems as if a great disaster has struck the land and its people, but there has been no tsunami, no hurricane, no earthquake, neither flood nor mudslide here. We see pictures of people, brought really close up, real live characters going through unbelievable daily injustices and torment. The ruthless exploitation of the working people, deaths of the hapless in villages, women forced into prostitution and scourged by AIDS, lungs assailed by poisonous gas, all consequences of international relations glamorized so often by the great powers of the earth, which come by the name of “free trade,” the “free market economy”—and in these days, “globalization.” What these words really mean for the people comes out stark and real.

In the 1960s a new species of fish, the Nile perch, was introduced into Lake Victoria as a “little scientific experiment.” Prior to this, Lake Victoria, the largest lake anywhere in the tropics, was teeming with about 400 varieties of fish. Many of the other species eat up the decaying algae, an overgrowth of which could consume the oxygen in the lake and hence their spread could suffocate the fishes. Thus the wide variety of fish constantly ensured adequate supply of oxygen in the lake. But this new breed is a voracious predator that even cannibalizes its own young. It can grow up to almost double the size of an adult human, weighing as much as 200 kilograms, about 440 pounds (40 kilo fish, about 88 pounds, are common in the daily catch). It has devoured 95 percent of the native species in a single decade and is reproducing itself very quickly. The rapid fall of the oxygen level, owing to the disappearance of other, smaller fishes that feed on algae, endangers all life in the water of the lake. In the end the Nile perch too will become extinct. This ecological state of affairs is bringing 14,000 years of evolution in this lake to a tragic end.

The villain of the film is ostensibly the Nile perch. But an even greater predator, with a more voracious and never-ending appetite for profits and power, a far bigger player on a global scale—the imperialist political, economic and social system and its international relations—soon comes into sharp relief.

Fat juicy fillets for Europe and Japan, lean pickings for locals

Sauper’s camera takes us into the factory, a hive of activity. Here the workers toil away, expertly carving out the fillet of the denizens from the deep and tossing their heads and skeletons onto large waste bins, cleaning away the scales and fins, sharpening their knives, loading and unloading crates and bins of fish and waste. The fillet themselves are loaded onto conveyor belts that carry them into machines for further processing and then to the packing area. A quality control worker tells the camera that most people in the country cannot afford to eat the fillet. These are strictly for export. When asked if he is aware that a famine is looming over Tanzania, he looks bewildered… and falls silent.

Just as painful to watch are scenes of Mr. Diamond, whose factory employs 1,000 workers, and the men around him, the smug and gloating local exploiters (his business partner and his management staff). “We are the pioneers here,” Diamond proudly boasts. “The fishing industry has provided jobs for all the people, all around the shores of the lake, all the people in the region, in Mwanza and Musoma, and even as far as the central region, have work and are totally dependent on the fishing industry.” Diamond gives the impression that there is general prosperity and well-being in the region owing to the export of Nile perch fillets. Each day, two planes land and take off laden with fish and “the airport is busy,” he says. Diamond further reveals that many entrepreneurs have successfully applied for loans and financial support from the World Bank and are today doing very well in the fish industry.

Sauper immediately takes us into a slum area on the outskirts of Mwanza. Amid the squalor of the surroundings, “Life Tastes Good,” declares a large Coca-Cola billboard, one of many that adorn the landscape. And giant-size concrete models of Coca-Cola bottles, complete with its notorious label, stand here and there amidst rows and rows of houses—frames of sticks and tree branches upon which hang plastic and canvas sheets. Trucks unload the waste on a vacant ground, surrounded by the shantytown. The people here, mainly village women around the dump, have erected very many large racks and frames of wood and sticks, upon which they hang or place the salted fish skeletons with heads intact, to dry under the sun. Young boys chase away the white cranes and crows hovering overhead, descending, trying to pick at the fish, along with a myriad of flies and other insects. While the workforce in the factory Saupert visited employed overwhelmingly male and young, here on the dump women struggle for their families. The stench of the rotting fish almost assails our nostrils.

A one-eyed woman working among the garbage complains that the poison in the air causes blindness and respiratory problems for the folks around here. There is a dangerous level of ammonia in the atmosphere says the caption. A middle-aged worker hanging up fish remains says that life is looking better for her. In the “backcountry” where she used to be a peasant, she says, there is no work, no way to earn a living, no money, no food and clothing. It is better to earn some cash here than to stay in her village, she declares. Here, at least, she says, she can earn her livelihood among the filth and odor… She looks around and almost whispers that she cannot talk any more. Her boss is cautioning her to say no more and get on with her work.

Sauper does not make any conceptual remarks here, but the footage makes it plain as bright daylight. The global market—world capitalism—is the greatest predator the world has ever seen and its much vaunted “magic” is able to turn human beings into scavengers scrambling for whatever they can to survive.

Unexpected talents appear too. Local self-taught artist and chronicler, young Jonathan shows his multi-colored crayon drawn pictures of life around him. His picture collection includes the giant Ilyushins landing at Mwanza airport, children smoking drugs in dark alleys; he too was like that he confides. It was to forget the pangs of hunger and hardship. He has also drawn pictures of children sniffing glue, older boys fighting with broken bottles, a body sprawled on the ground, bleeding, a young woman begging for money from a driver of a stationary car, “for her living so that she could survive.” “Perhaps she is a prostitute,” he surmises. Jonathan relates stories of orphans, fishermen’s children abandoned by drunken parents, parents suffering from AIDS.

Jonathan also tells of a time when an airplane was raided by the authorities and a large cache of modern firearms was discovered on board. Those weapons were destined for other African countries, Jonathan says. When asked how he came to know of this, he replies, “It was in the papers, on radio, on TV.”

“We sell our country”

Once again in Mwanza town. The scene: a conference hall. A delegation of European Union Commissioners sit on one side of a conference table. An exuberant delegate congratulates the political representatives of Tanzania’s capitalism, seated on the other side, for the high quality of the fish produced and the “world-standard” sanitary and hygienic conditions under which they are processed and packaged for the markets of Europe. Fish from the lake region account for 25 percent of Tanzania’s export earnings, we are told. They provide the perfect illustration for the Marxist term comprador capitalist, meaning capitalists in an oppressed country whose business is dependent on the international imperialist economy and who therefore are politically subservient as well.

We also see an international conference on ecology, with top bureaucrats and leading business and political figures from abroad and Tanzania, including a government minister and his delegation. The audience is shown a documentary film. A film within the film. It is about the Nile perch wiping out other species of fish in Lake Victoria and choking all life in the water.

The honorable minister is not at all pleased with the theme of the film. “We are all here for one purpose only,” he announces loudly. That is, “How we can sell our country, sell our lake, and our fish.” “Film-making is a process,” he declares, in which a filmmaker takes the parts he feels important for his story and discards others he deems irrelevant. “But here, the producer jumps suddenly from one part to another… Of course, not all of the lake is polluted, dirty and green with algae and lacking in oxygen.” The lake and its fish bring in vital income to the country, contends this fat minister. “We have to look at the positive side of the fishing industry. We cannot be all negative.” We have to market our country. We look to the positive side and “sell our country.” The chairperson of the meeting, apparently an important state functionary, does not demur. “We should not be one-sided, all negative. We weigh the positive against the negative and sell the country.” Indeed those in authority are shamelessly chorusing before Sauper’s camera that Tanzania’s human and natural assets must be sold to the highest bidder.

Victoria Blues

Back in Diamond’s office. “These are tough times,” Diamond says. Business has slumped these days. Oversupply and a glut in the European market. Not long ago, he asserts, he used to ship 500 tons of Nile perch per day. How many people can be fed with the 500 tons? He has no idea… Two million people, the caption on the screen immediately states.

An East African newspaper lies on Diamond’s table. Its headline warns of famine. Diamond expresses his doubt on the accuracy of the news, yet he acknowledges that there is a drought and rice cultivation requires a great deal of rain. There will be severe shortage of rice in the country and prices would soar the following year, he admits. When asked what is going to happen as a result, he shrugs and says that the state would import food and other stuff from abroad.

While drought and other natural disasters trigger food crises, the previously food self-sufficient subsistence farming sector is destroyed through the import of cheap grains and manufactured foodstuff from abroad (mainly from imperialist countries). This is what has caused so many peasant communities to abandon food cultivation. Such economics is strenuously forced on third world countries by the IMF and the World Bank in the name of free trade, economic liberalization and structural reforms. These have given rise to wholesale ruin and uprooting of rural communities, resulting in chronic food shortage in the countryside. This is the underlying reason for the increasing poverty and food shortage in many African countries. To compound this problem, food subsidies are discontinued at the IMF’s insistence, while prices of imported food items rise—making them unaffordable for the poor.

Like many Sub-Saharan African nations, Tanzania used to grow enough food for its people. Now its economy is held for ransom by the global market economy, inexorably pushed by the imperialist system, by its workings, by its ever-widening worldwide structures, ever-tightening nooses around people’s necks, as well as by the state. It has become dependent on food imports as local farming communities abandon their fields and villages in search of quick cash, that is, working to export fish, and toiling on plantations to produce export crops for the world market. When the remaining food crops fail, as is happening now in Niger and Malawi, people die. In producing riches for imperialist capital, the people have become prisoners of a system whose other product is starvation.

Each day, giant aging Soviet-era cargo planes land at the Mwanza airport to take Nile perch fillet to Europe. The airport is also where the Russian air crews—pilot, co-pilot, navigator and engineer—do their own improvised maintenance work on the plane, rest and recuperate—and also spend their time and money enslaving local women.

Christmas presents: guns for Africa’s children, grapes for European children

A Russian pilot admits that he had previously unloaded military equipment in Afghanistan. When asked about arms delivery to African countries, he is evasive; he at first denies it. When the question is put to him somewhat differently, he changes the subject. “This is my co-pilot,” he jokes, smiling at a photo of a cute little kitten in his hand. He finally admits that he once delivered modern weapons to Africa—tanks to (civil) war-torn Angola. After delivering arms to Angola, he flew to South Africa, loaded the plane with grapes and returned to Europe, he reveals a little further. “The children in Africa receive guns for Christmas and the children in Europe receive grapes. Here is a little story from me to you.” After reflecting on this for a while he solemnly declares that he wants all the children of the world to be happy.

On a hilltop overlooking the town, with dark clouds gathering above, Richard Mgamba, a local investigative journalist, reveals that the Ilyushins don’t come into Mwanza empty. They bring in modern arms and military equipment meant for the Democratic Republic of Congo (where 4 million people have lost their lives in the last five years of civil wars) and other conflicts in Liberia, the Sudan, and elsewhere. Mwanza airport is a conduit for these arms deliveries from Europe, Mgamba discloses, bringing additional profits for the transport companies that own the planes. All the European nations have security apparatuses and intelligence services—why can’t they stop the arms trafficking? he angrily demands. Many viewers will conclude that they don’t want to—because the imperialists ship arms to stir up and fuel local conflicts in order to serve their own contending interests.

Condoms and sin, Hallelujah! and all that

In one of the most heart-rending scenes, the film takes us to see AIDS-stricken women, one of whom can’t even stand up. Gaunt, sullen, great sorrow and guilt absolutely written on her face, neighbors and relatives help her to her feet by as the camera zooms in. Others sit glumly, looking sullen and forlorn, staring into the camera.

A funeral service for an AIDS victim in the village. A close-up of faces. Young, well-cut cheek frames, but with death stalking. The villagers sing a funeral hymn, expressionless, yet there is so much beauty in the dirge. Beauty in deep sorrow. The villagers bury their dead, hoeing the dirt on the coffin.

The migration of people from the “back country” villages to regions or cities promising employment opportunities has depleted the population in rural areas. And those arriving at places like Mwanza and the Lakes and who do not find work as fishermen or factory hands end up scavenging for food and other bare essentials.

Prostitution is widespread around the Great Lakes region, and so is HIV and death by AIDS. In the village of Ito, M’Kono, an ex-school teacher and village leader, tells us, “Some people say the women in these parts are harlots, but it is not their fault, they are not to blame. They are forced to become prostitutes.” He explains that women, many of whom have lost their husbands and fathers (to AIDS and crocodiles in the lakes), are flocking to Mwanza and other towns in the area seeking to sell their bodies for a pittance. Poverty has gripped the nation and prostitution is the only alternative for many widows and orphans. “It is a vicious cycle,” he says about poverty, prostitution, diseases, and death.

“In the past,” M’Kono says, “there was a scramble for land in Africa by the great powers of Europe.” Nowadays, he declares, “it’s the scramble for Africa’s natural resources.” It’s a case of the “survival of the fittest,” M’Kono says. Talking of the fittest today, as it was in the past, it is the Europeans who are the strongest, and they come out on top. M’Kono observes, “It is the Europeans who possess the money, own the IMF, own the World Bank and the world trade.” It is they who bring in supplies of goods, profit from them and even benefit from the humanitarian relief aid. “It’s the law of the jungle,” he concludes.

Christian fundamentalism and hardship are obviously feeding into each other in the villages of the outlying areas. In a village nearby, a highly charged young man, well-fed and well-clothed, is holding a microphone in one hand, haranguing a gathering, gesticulating with boundless energy with the other. He hollers his praises to god and Jesus Christ, denounces the “devil” and calls on his parishioners to abstain from Satan’s temptations. He appears fierce, threatening, ending with a great Hallelujah! Amidst the extreme deprivation and squalor, it is clear that only the church has sophisticated electrical equipment. A film is shown of Jesus on board a fishing boat, hauling in a bountiful catch.

Reverend Cleopa Kaijaga, the village pastor, reveals that 45 to 50 or even 60 people die of AIDS every month in the area. In his small village alone 10 to 12 people have died of the disease monthly. As a pastor, he says dolefully, he advises the fishermen to stay away from prostitutes, and the womenfolk to keep away “from the business of prostitution.” The prostitutes seek out fishermen bringing in their catch every day. There is an air of despondency about him as he reflects on this—and this is really heart-wrenching—and yet unnerving. When asked if he would recommend the use of condoms, this preacher says no, claiming not only that condoms—the only means of prevention against HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases—are dangerous, but also that their use is a “sin against God’s law” and that instead women should abstain from sex outside marriage. This hard-sell brand of Christianity of the evangelical Protestant kind is a major export of the U.S. ruling class to these parts.

“The people here hope for war”

The immense sadness of watching infants and street-children so young lose their childhood, their innocence, is matched by the cynicism of Raphael, a retired soldier, now a fisherman by day and a night watchman at the National Institute of Fishery. He tells us how the previous watchman was hacked to pieces by thieves. All smiles now, and paid no more than a dollar a night at the institute for fish research, he calmly informs Sauper’s camera crew that he would readily shoot to kill (with his bow and poisoned arrows) any would-be burglar who dared enter the compound he is guarding. He muses aloud his regrets for being poorly educated and thus earning a very low income and yet being unable to rejoin the army owing to his age. And how things would turn for the better for him if war broke out once again.

Raphael tells Sauper that there are no hospitals or clinics around the place he lives and works. People needing medical care would have to travel great distances (to big cities) for treatment. Tanzania’s social services have been wrecked by imperialist-ordered policies. In order to extract debt repayment, from the 1980s through today, the IMF demanded that Tanzania slash state funding for health care and other social services, thereby making the people more vulnerable to chronic illness and diseases. The 2005 IMF report hails Tanzania’s favorable economic growth, an economic success story! This “success” has come at the cost of the poor becoming even poorer, a widening disparity of income and wealth, illiteracy, diseases and the death of so many young people.

Raphael tells the camera that war is good for the people around here. The army pays a good salary, he says, and takes good care of soldiers. “Many people hope for war here,” he adds. “Are you fearing war?” he asks Sauper. “I’m not fearing war,” Raphael adds reassuringly.

No amount of description can adequately do justice to Sauper’s Darwin’s Nightmare, which ends with a grim, but sad note: two very young boys taking turns to sniff into a bottle of glue and smoke a cigarette before they fall asleep in a dark alley as a motor-car speeds past a street light. This scene, like others, is never to be forgotten. Through his superb cinematography Saupert offers glimpses of how the European Union, IMF, World Bank and the very workings of international finance capital have wrought such dire consequences for a third world nation.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.