Revolution #53, July 16, 2006

Review:

LEGACIES: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery

|

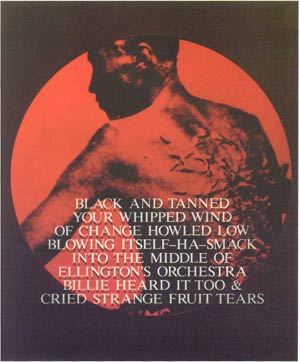

| Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953),

Black And Tanned Your Whipped Wind of Change Howled

Low Blowing Itself-Ha-Smack into the Middle of

Ellington's Orchestra Billie Heard It Too & Cried

Strange Fruit Tears , 1995-96,

Color coupler print with sandblasted text on frame

glazing Collection of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, Image courtesy Solomon Fine Art. |

The “peculiar institution.” This smugly ironic term has long been used to describe that chapter of the “American pageant” marked by people actually owning and enslaving tens of millions of other human beings.

How thoroughly did the barbarous American system of slavery shape every aspect of the history and consciousness of this country, from the earliest years right up to today? Check out some scorching evidence currently on-view at an art exhibition at the New York Historical Society Museum: LEGACIES: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery.

The neck. Kerry James Marshall’s three bright white canvases (Heirlooms and Accessories) showcase massive and gaudily grotesque necklaces with hanging lockets featuring grainy photos of white women staring out lovelessly. Weird. Slowly, the ghosted background comes into focus: it is the infamous photo of an Indiana lynching. Two Black men hang by their necks from trees. The women are part of the mob.

A few feet away in the museum another necklace is on display—this one listed as a “slave collar.” Engraved in wedding script on a small silver plaque located right under the chin is “J. Davis No. 101”—the name is that of the wearer’s owner. The item is part of a complex installation (Liberté/Liberty) which features two plaster-white busts of George Washington; on their backsides hang rusted-out slave leg chains and “shackles worn by a Georgia slave.” A bust of Napoleon gets paired with a portrait of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of a slave revolt that drove out the French colonialists in Haiti. Standing before the assemblage is a wooden tobacco store statue of a Black man, holding in his hand the crimson “Phrygian” or “Liberty Cap,” first worn by emancipated slaves in ancient Rome. The artist, Fred Wilson, is famous for “mining” museums and re-assembling objects to reveal the actual social relations routinely obscured in the falsified history told by the exploiting class.

On one wall, mirror-image indigo-blue photographs of two unconquered African women in their own stunning necklaces and headdresses are looking at each other, seemingly from across oceans. Emblazoned towards the bottom of the two photos: “FROM HERE I SAW WHAT HAPPENED…AND I CRIED.” This piece by Carrie Mae Weems has haunted me for years. You can never un-know what you learn here about what the institution of slavery in the “New World” meant for those in Africa whose husbands and wives and children were ripped away.

Between the two women, Weems has placed a red and black duotone version of the well-known U.S. War Department photo of “freed slave Peter” entitled “Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me.” Capturing the dialectic of this cruel history with precision and poetry, the artist prints across Peter’s lacerated back the legend: “BLACK AND TANNED YOUR WHIPPED WIND OF CHANGE HOWLED LOW BLOWING ITSELF—HA—SMACK INTO THE MIDDLE OF ELLINGTON’S ORCHESTRA BILLIE HEARD IT TOO & CRIED STRANGE FRUIT TEARS.”

The hands. How would it actually feel to grow up with the certain knowledge that you—and every female relative and friend—is subject to rape by any white man, or boy, who decides to afford himself that inalienable “right”? Ten minutes standing in front of the video at the center of the Mammy/Daddy installation, created by Jacqueline Terry and Brad McCallum, opens a portal to this unimaginably toxic place. Picture this: A dark, high-ceilinged ballroom, dramatically lit by the moon. Two people, one a nattily dressed white planter, the other a Black woman slave, are harnessed, back to back and head to feet, onto a rotating contraption spinning them round and round, Ferris-wheel-like. As the man emerges upright, cutting the air with an imperious hand gesture, the woman is thrust upside down. When the woman rotates into view, a look of defiant anguish on her face, her hands clutch her face and belly, then reach up as if to fly or swim her way out. Never happens. Next scene is a close-up of white hands grabbing her torso as the languorous music flows on in tempo with the endlessly revolving machine. In the background, an occasional thunderclap erupts, or a man’s cackle. Turning away, one confronts a disturbing set of objects: the actual garments, hers and his, white and black, laid out in a long glass vitrine, feet to feet. A blood-red mound of silk billows between them. Hovering above are life-sized casts—in color—of the owner and slave.

The torment awaiting runaway slaves fills one entire room in the exhibition. In The Loophole of Retreat, Ellen Driscoll dangles a line of rotting white pillars, sinister replicas from a planter’s mansion. They hang along one side of a rough-hewn wooden space-capsule-like shelter. Walk inside and shut the door and you find yourself in a pitch-black cavern, a simulation of the claustrophobic attic space in North Carolina inhabited for seven years by Harriet Jacobs, a runaway slave escaping a sexually marauding slave master. As the eyes adjust, a slow stream of images (a window casing, a child’s hand…) appear on a floating circular disc—projections from revolving objects hung above this structure which turns out to be a gigantic camera obscura, the beam of light the only lifeline to the world outside. Harriet eventually made it to the north and survived to tell her story in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Resistance runs through LEGACIES—manifested in the courageous and unpredictable ways enslaved people fought to get free and claim their humanity. It is worth a visit to the exhibition just to stand before Faith Ringgold’s Slave Rape Story Quilt, a patchwork of brilliantly colored batik surrounding a stark drawing of bodies and bones and a hand-written chronicle of a girl-baby, Beata, born on the deck of a slave ship who lives on to defy her captors.

Lorenzo Pace’s minefield-garden of memories (hemmed in by a white picket fence) is conceived around the original iron padlock and key which at one time shackled his great-grandfather, Steve Pace. Nothing can prepare you to look upon this ominous piece of hardware worn by an actual person whose family you have come to know. The lock and key, which the artist inherited from his uncle, are also the inspiration for Pace’s mammoth black stone monument commemorating slaves in America (Triumph of the Human Spirit) that was erected a few years ago in lower Manhattan near the recently unearthed African Burial Ground.

One notable piece in the show (Leader) by Betye Saar takes you from slave days right into the future. On a vintage washboard (actual brand name: “Leader”), the artist attaches a painted metal “Mammy” figure, on whose long white apron is written: “Oh these cold white hands manipulating they broke us like limbs from trees and carved Europe upon our African masks and made puppets.” (Henry Dumas)

Largely the work of Black artists, the exhibition (which runs through January 2007 and may travel to other cities) was curated by Lowery Stokes Sims of the Studio Museum of Harlem. This is the Historical Society’s first-ever contemporary art show, and it is a brave one. New York Times critic Holland Cotter wrote in his favorable review: “American slavery—what it did, what it is still doing—remains an incendiary topic…[and this show] keeps you looking, thinking and rethinking.”

LEGACIES connects with two earlier shows organized by the New-York Historical Society: Slavery in New York, and Civil Wars: New York and Slavery 1815-1870. The shocking “postcard show,” Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, was also exhibited at this museum a few years ago.

In 1867, Marx sardonically remarked in Capital: “The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalized the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

This significant art exhibition looks at a piece of this history, refracted through the eyes of artists who dare to depict, in excruciating and unforgettable ways, this cold truth: slavery lies at the center of what America was—and is today. As someone wrote in the museum visitor’s book on July 4, 2006: “Slavery was the basis of the building of America… Let this be taught as it was…”

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.