From a Reader

She Who Tells a Story

Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

January 13, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Out of the cauldron of war, invasions and occupations, Obama’s drones and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism—out of resistance to Islamic theocracy in Iran, the Arab Spring and the subsequent military coup in Egypt, comes an exhibition of brave and insightful work by 12 photographers. Given the forces colliding in the region, it’s not surprising that some of the most radical and imaginative artistic expression is coming from women. Some of the artists on display until January 12 are part of Rawiya, a small collective of female photographers in the Middle East—the translation of Rawiya is “She Who Tells a Story” and gives the exhibit its title.

Much of the work is commentary on the division of humankind along lines of sexuality and gender and the domination of women by men made inviolable under Sharia laws. Some of these women are working in exile, some of them are bi-national, and some of them are continuing to work in their home countries dealing with censorship, the challenges of being among the first female photojournalists venturing out onto streets and into war zones, risking their own personal safety, potentially bringing “dishonor” to their families and having to coax their female subjects into allowing themselves to be photographed.

A panel of moving video images by photographer Newsha Tavakolian titled "Listen" features six Iranian singers—their faces full of emotion but there is no sound—you cannot hear their voices. The accompanying text reads

“Imagining a dream.”

“Eyes closed, mouths open as if in a dream. Standing, facing us with their backs to the darkness, they sing soundless; they have standing here, singing for themselves for a long time, imagining us. Standing, facing the days of tedium. Facing a world that has adorned them with a false crown.”

“Standing, waiting.”

Forbidden by Islamic law to perform by themselves in public or to produce recordings—the next panels are imaginary album covers created for each artist and each has an empty CD case as a statement against the restrictions they face. The covers include irreverent depictions of women, one of a young woman in red boxing gloves with Farsi words dripping from the sky, or images of the same woman standing in pounding ocean surf.

_Newsha-Tavakolian-600.jpg)

Don’t Forget This Is Not You (for Sahar Lotfi), 2010, Newsha Tavakolian

Reproduced with permission. Courtesy of the artist and East Wing Contemporary Gallery. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Palestinian photographer Rula Halawani presents “Negative Incursions” shot during the Israeli incursion into the West Bank during the second Intifada in 2002. The images capture Israeli tanks bulldozing homes and the grief of displaced people in the rubble of the aftermath. Displayed as negatives, Rula Halawani describes her purpose: “As negatives they express the negation of our reality that the invasion represented.”

Untitled XIII, 2002, Rula Hawani

Courtesy of the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery, London. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Working with contradictions, the artists provoke people to look at things usually taken for granted from a different angle. Shadi Ghadirian counterposes the “domestic realm” of women with the “male realm” of war. A photo of a bowl of fruit—with a hand grenade nestled in the still life. A sepia portrait series of a woman in a chador holding banned objects. Nermine Hammam takes pictures of soldiers on duty in Tahrir Square and digitally manipulates them to take them out of context and situates them in bucolic nature scenes taken from her collection of traditional Japanese landscape paintings. This includes an iconic scene of a woman being violently attacked by soldiers in Tahrir Square—her abaya torn open to reveal a brightly colored bra. Nermine explains that this image, published and distributed by Reuters, quickly eclipsed the brutality of the soldiers and added a second violation, turning her into an object of titillation as the image went viral. Rania Matar’s series “A girl in her room” juxtaposes teenagers from the greater Boston area and Lebanon, and the self-expression of their bedrooms—or just a small individual space on a wall of a one-room apartment in a refugee camp.

Stephanie, Beirut, Lebanon, 2010, Rania Matar

© Rania Matar. Courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons, Boston. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The impact of Western imperialism on how people not just in the West but in the Middle East see themselves is a tension that runs through much of photographic work. Lalla Essaydi from Morocco addresses this most explicitly—Essaydi takes the 19th-century European "orientalist" paintings and tales like The Thousand and One Nights and the musical composition Sheherazade, and creates an image of a woman arranged in an "odalisque" pose. Odalisques were slaves and concubines, and in the photo the subject is draped over cushions in a chamber with her hair flowing back. According to the exhibit notes, the image is a comment both on the way Western colonialists produced voyeuristic images of women in harems and the artist’s fear of increasing reactionary restrictions on women in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The image appears as luminous and golden but as you approach closer you realize the gleam in the image is constructed with bullet casings. Like the Ghanian sculptor El Anatsui who works with bottle caps to make amazing metallic hanging sculptures—Lalla Essaydi has worked with the detritus of wars in the region with provocative effect. She also works with the traditional use of henna in Moroccan celebrations of puberty, weddings, and childbirth and draws calligraphy over the entire image including over their skin. Calligraphy is a sacred Islamic art reserved for men—and the exhibit notes explain that by appropriating this she is giving women a way to speak and express themselves in her art.

Bullets Revisited #3, 2012, Lalla Assia Essaydi

Reproduced with permission. Courtesy of Miller Yezerski Gallery Boston; Edwynn Houk Gallery New York. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Iranian photographer and filmmaker Shirin Neshat has a whole body of work that is also situated between the patriarchal legislation of women under Sharia law and the domination of the Middle East by the West, particularly by U.S. imperialism. As she put it in a recent talk, Iranian artists have to fight two battles at once in different realms—one the depiction of Iran produced by the Western media and the other against the atrocities of the Islamic fundamentalist regime. Shirin returned to Iran after attending school in the U.S. She arrived after the Islamic revolution and went with an uncritical view. This changed slowly as she sharpened her analysis and the blade of her art—and therefore facing censorship, imprisonment, and torture that artists considered a threat to the regime were facing—made the decision to go into exile.

Speechless, 1996, Shirin Neshat

Copyright Shirin Neshat. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by Jamie McCourt through the 2012 Collectors Committee, M.2012.60. Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Perhaps the most discussed photos in the exhibit is a series titled “Mother, Daughter, Doll” by Boushra Almutawakel from Yemen. The nine photos begin with a mother (Boushra used herself and her daughter as subjects) her daughter and doll dressed in what was more typical Yemeni custom—a plaid coat and pastel headscarf—her daughter with no head covering. With each successive photo the dress becomes darker, the hands more closed, the faces more guarded, until midway through, mother, daughter, and doll are cloaked in the niquab with faces and hands covered until in the last photo the only thing left is a black pedestal—the woman, daughter, and doll have been disappeared. Boushra Almutawakel—the first female photo journalist in Yemen describes the photo essay as an expression of her concern for the growing religious extremism in Yemen—but she’s also conflicted herself about the veil and this has informed an exploration of this subject in quite a few of her projects—one series showing the roles reversed with men in the veil and women without, another showing the way Western women cover themselves with make-up while women in the Middle East cover themselves with the veil. Another shows the Middle Eastern version of a Barbie doll complete with niquab.

Mother, Daughter, Doll series, 2010, Boushra Almutawakel

© Boushra Almutawakel. Museum purchase with funds donated by Richard and Lucille Spagnuolo. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

This ambivalence runs through some of the artists’ work—seeing the veil as part of their cultural identity or allowing for the anonymity and protection the veil provides women in the public spaces when society (everywhere) is saturated with misogyny.

Caught in between the rise of Islamic fundamentalism on one side and the domination of the West and in particular imperialism with its bogus claim to be the liberator of women—artists are shining a light on this predicament for women in the region—but nearly absent is the ability of these same artists to see the possibility of a world without the domination of half of humanity by the other. Still hidden is where the oppression of women arises from and the fact that there is a basis for this age-old and outmoded way of thinking to be uprooted and superseded at this point in human history.

Sharia law, the segregation of women from men, the view that a woman is nothing more than the property of a man and her sexuality as something to be controlled by men, alternately objectified and stigmatized as shameful, the compulsory veiling of a woman’s body is intolerable in the 21st century. Any woman or man can and should be able to say this without reservation—anywhere on the planet. This is what heroic women in the Middle East are risking everything to resist. It’s why the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in the Soviet Union led people and freed a generation of women to cast off the veil in the nations formerly oppressed by Russia at the same time the world's first socialist state was legalizing abortion and decriminalizing homosexuality. It is no more essential or immutable to culture than arranged marriages, female infanticide, and binding women’s feet were in pre-revolutionary China. Those who wanted to uphold this as “Chinese” culture had tens of thousands of years of feudal traditions to claim but that did not stop tens of millions of women from leaping at the prospect of liberation when the Red Army marched through and for them to continue to be a driving force in the Chinese revolution—before capitalism was restored when the first socialist revolutions were defeated.

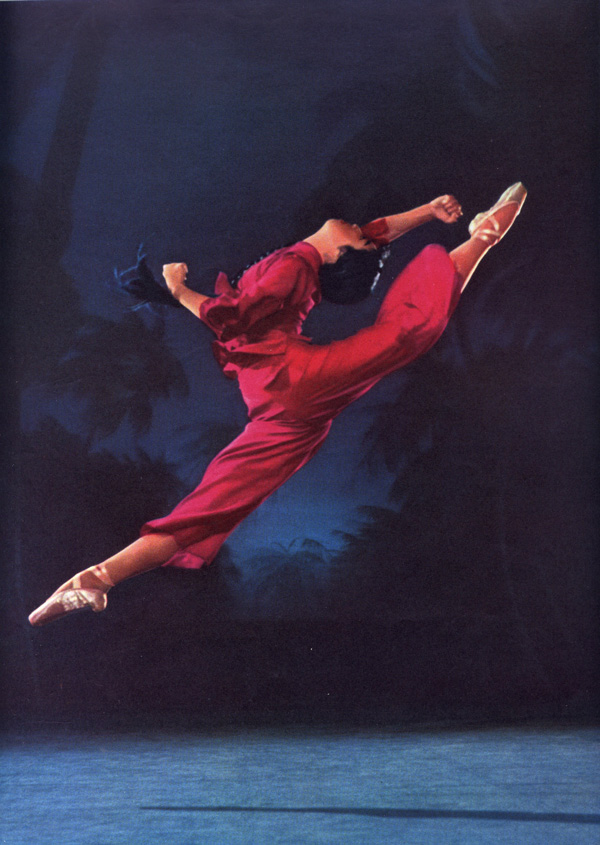

A scene from The Red Detachment of Women, film of a revolutionary ballet created during the Cultural Revolution in China—when China was a genuine socialist society, before the restoration of capitalism in 1976.

For some of the artists, family honor and patriarchal traditions appear so deeply embedded that it seems improbable that this will change—but what people currently think does not determine what is just nor what is possible. In the U.S., where there has been a long history of Black people’s struggle being deeply intertwined with the struggle for the liberation of women, the 1960s produced a generation of people who experienced a repolarization of millions of people and how they transformed their thinking and deeply embedded beliefs through the convulsions of the civil rights and Black liberation movements. One of the first truths young people grabbed onto was an understanding that if you were taking part in holding your foot on the neck of another human being—if you held to the groundless belief that Black people were inferior and tolerated a society segregated on the basis of race where Black people were legally designated as “lesser”—then ALL of society was bound to be poisoned and stunted by that injustice. There wasn’t anything about Jim Crow, Confederate culture, or the institutionalized racism in the country as a whole that was morally acceptable or justifiable.

Different classes and class interests see questions of culture and morality especially as embodied in the treatment and status of women with completely different and opposed outlooks, sensibilities, and aspirations.

Veiling under burkas and niquabs, a culture of rape and pornography, feudal honor killings, the marketing of women as sexual commodities, as prizes of war and trophies of success, the control by men of women by stripping them of any self-determination over their own reproductive decisions—these are essential and indispensable to carrying forward and buttressing patriarchal systems that depend on oppression and the subordination of women. Whether it is capitalism that traffics in the degradation and exploitation of women anywhere the dollar and its military reach, or outmoded feudal forces in the oppressed nations who may oppose the West but ultimately look to find their own reactionary niche in the imperialist world market—none of it is necessary, desirable, or in the interests of the vast majority of humanity.

All over the third world people are being thrown off the land and into the world’s megacities, often in the sprawling slums and shantytowns. Uprooted from the traditional means of life and hurled into miserable and uncertain conditions, people often turn to movements like Islamic fundamentalism to try and find some kind of anchor in the midst of all the dislocation and precariousness of “modern” existence. The majority of the world's population has shifted from rural to urban in just a few decades and this rapid urbanization is taking place in the context of domination and exploitation by foreign imperialists who align themselves with local tyrants. After decades of counterinsurgency in the Middle East—where the West systematically targeted and decimated secular opposition to imperialism (and often funded and fed reactionary religious movements to go after the secular left)—all this has strengthened the growth of Islamic fundamentalists who portray themselves as the opposition to Western decadence and foreign domination.

These contending outmoded and reactionary poles of imperialism on one hand and Islamic fundamentalism on the other, as Bob Avakian has pointed out, actually “reinforce each other even while opposing each other.” And while Avakian makes clear that the greater damage is being done by imperialism, he also makes the point that “If you side with either one of these ‘outmodeds’ you end up strengthening both.”

Culture, like human nature throughout human history, is a moving target—undergoing subtle, even imperceptible changes that often give rise to dramatic ruptures in what had been the social norms.

Today the family—worldwide—is undergoing a tidal wave of change. Women in large parts of the world have been driven by the workings of imperialism into the job market—into the sweatshops of Bangladesh and Cairo, the high-tech call centers of Bombay or into the universities of Tehran. In the U.S., jobs once held only by men have moved overseas and women are supporting the family by working at the local Walmart. In the U.S., the majority of people no longer live in the traditional nuclear family. In fact, increasingly, the nuclear family is practicable only for the more privileged strata. And that traditional nuclear family arrangement is often made possible by a woman who has traveled halfway across the world to be a nanny—often leaving her own children behind. In the U.S. today, of the 2.3 million people incarcerated in U.S. prisons, more than half are parents of children under 18. That translates to 2.7 million children with one of their parents in prison—a disproportionate number of them Black people with a historical legacy of children being torn from their parents' arms in one form or another since slavery.

This upending of the traditional family opens a veritable Pandora’s box of unforeseen worldwide consequences and social forces. The last decades have witnessed youth revolts and cultural movements with progressive aspirations and subversive views of sexuality, gender and equality colliding with ugly currents of resentment, as male entitlement is disrupted and eroded by the anarchic workings of the capitalist economic system. The very workings of capitalism are pushing increasing numbers of women to work, to maintain a middle class existence or simply a below subsistence existence. And that entry of women all over the world into the workforce is undermining traditional family arrangements. Capitalism and capitalist globalization undermines the family even as the patriarchal family is—for those who rule society—essential for social stability and reinforcing the subordination of women. From misogynist "Guy Culture" to reactionary religious movements, that promise to restore man’s domination over his wife and children and bring back order and the “good old days,” these reactionary movements and social trends are embraced, funded, initiated, or aided by powerful forces in the ruling class.

When I look at the iconic photo of the young women being brutalized in Tahrir Square, I can’t help but think about the push and pull of these currents with their antagonistic views of what it is to even be human—in bitter contention worldwide—and a prescient statement made by Bob Avakian in the 1980s:

"The whole question of the position and role of women in society is more and more acutely posing itself in today's extreme circumstances…. It is not conceivable that all this will find any resolution other than in the most radical terms.... The question yet to be determined is: will it be a radical reactionary or a radical revolutionary resolution, will it mean the reinforcing of the chains of enslavement or the shattering of the most decisive links in those chains and the opening up of the possibility of realizing the complete elimination of all forms of such enslavement?”

What is needed and eminently reasonable is carving out of this morass a whole other way—of liberating women through communist revolution. Led with a communist outlook revolution would, to quote from the Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America (Draft Proposal) from the RCP:

Section 3. Eradicating the Oppression of Women.

1. The oppression of women emerged thousands of years ago in human history together with the splitting of society into exploiting and exploited classes, and this oppression is one of the cornerstones of all societies based on exploitation. For the same reason, the struggle to finally and fully uproot the oppression of women is of profound importance and will be a decisive driving force in carrying forward the revolution toward the final goal of communism, and the eradication of all exploitation and oppression, throughout the world. Based on this understanding, the New Socialist Republic in North America gives the highest priority not only to establishing and giving practical effect to full legal equality for women–and to basic rights and liberties that are essential for the emancipation of women, such as reproductive freedom, including the right to abortion as well as birth control—but also to the increasing, and increasingly unfettered, involvement of women, equally with men, in every sphere of society, and to propagating and popularizing the need for and importance of uprooting and overcoming all remaining expressions and manifestations of patriarchy and male supremacy, in the economic and social relations and in the realms of politics, ideology and culture, and to promote the objective of fully emancipating women and the pivotal role of the struggle for this emancipation in the overall transformation of this society and the world as a whole. This orientation, and policies and laws flowing from it, shall be applied, promoted, encouraged and supported with the full political, legal and moral force, authority and influence of the government, at all levels, in the New Socialist Republic in North America.

So I will end this correspondence by inviting people to look at the book of this exhibit, which is published by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and which can be found or ordered from Revolution Books, and to invite people to discover a whole other way the world could be—the most radical and realistic that has ever existed—uprooting the oppression of women by bringing about communist revolution, worldwide. Communism has been put on a more revolutionary, scientific and viable foundation due to the breakthroughs in communist theory, method and strategy made by Bob Avakian. A new synthesis of communism that is a real source of hope, especially for anyone who has dreamed of freeing humanity from traditions chains.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.