Interview with Larry Siems, Editor of Guantánamo Diary

February 23, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

The following is a transcript of a February 13, 2015 interview with Larry Siems, editor of Guantanámo Diary, by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, on The Michael Slate Show, KPFK Pacifica radio.

Larry Siems describes himself as “a lifelong advocate for freedom of expression and the power of writing.” He is the former director of the Freedom to Write and International Programs at PEN American Center and the author of The Torture Report: What the Documents Say About America’s Post-9/11 Torture Program (2011).

Michael Slate: Larry Siems, welcome to the show.

Larry Siems: Thanks so much for having me.

Michael Slate: It’s fairly unique, because we’re doing a story around a book, and we can’t talk to the author, but we can talk to you, who played a very important part in getting the book out into the world even though you’re not the author. In some ways, you actually contributed to writing it. Can you tell people what the book is, and how you came to be involved in this?

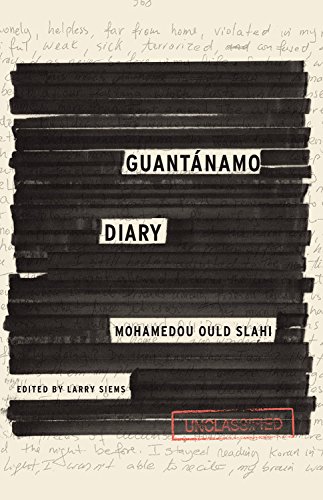

Larry Siems: Sure. The book is Guantánamo Diary, by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who’s a prisoner in Guantánamo to this day. He wrote the book in 2005. He handwrote it in English, which was his fourth language, over a period of months in an isolation hut that he had been dragged into a couple of years before as part of one of the most brutal tortures that happened inside of Guantánamo. As I say, he wrote the book in 2005, beginning in March of 2005, when he found out he was finally going to meet his attorneys, and he gave several pages to Nancy Hollander and a partner of hers at the time, Sylvia Royce, when they visited him in March, 2005, and with their encouragement he continued to write and completed the manuscript by September.

Like everything that a Guantánamo prisoner writes, the manuscript was immediately considered classified, from the moment it was created, and it was taken away and locked in a secure facility outside of Washington, DC, accessible only to his attorneys with their full top secret security clearances, and of course, they couldn’t talk about it or anything. And it remained there for about seven years, while his lawyers, led by Nancy, who are the real heroes of the story, carried out litigation and negotiations to force the government to declassify the manuscript and clear it for public release. That happened in the summer of 2012. They were finally able to give me the redacted version of his handwritten manuscript that formed the basis of this amazing book.

Michael Slate: This was quite a task for you—both a challenge and an opportunity to do something that was really unprecedented, both in publishing and in terms of the sort of medieval torture chambers that the U.S. has set up in Guantánamo, to really bring out the first voice that has been able to bust out there on their own, while they’re still in Guantánamo.

Larry Siems: Yeah, as you say, it’s a voice from the deepest void, and it’s such an amazing voice. It was amazing because in the summer of 2012, when I was handed this thing, I had a good idea of how remarkable it would be, because as you said, for the previous four years I’d been working on this project called the Torture Report. My job was to sort of sift through about 140,000 pages of documents that the ACLU had managed to get declassified and released through FOIA [Freedom of Information Act] litigation about prisoner abuse in Guantánamo, Afghanistan, Iraq and the CIA “black sites”—to go through these things and try to look for characters and narratives and try to put them together into emblematic stories of the torture program. And one of the characters that emerged most strongly was Mohamedou Slahi, because his torture in Guantánamo was so deliberate, approved at the very highest levels. His torture plan, they called it a “special project interrogation plan,” was signed off on by Donald Rumsfeld, the secretary of defense, and there’s a huge paper trail about the torture that Mohamedou describes in the book.

So I knew that it was likely to be a pretty harrowing story. I knew it was an epic story because he had been sort of dragged through a sort of global gulag of detention sites even before he got to Guantánamo. He had turned himself in voluntarily for questioning in his city of Nouakchott, Mauritania, and was essentially disappeared. The U.S. sent him on a rendition plane to Jordan. He was interrogated in a Jordanian intelligence prison for eight months. Then another CIA rendition plane took him to Bagram and then to Guantánamo. So I guess I knew it was an epic story. And I also knew, just because in these documents there were a couple of transcripts of his hearings inside Guantánamo that had little bits of his voice. I also knew he was quite a remarkable storyteller, with a great eye for detail, a really good sense of humor. So when I got the manuscript in 2012, like I said, I had a sense that it would be something quite amazing. But even so, I couldn’t imagine the depth of skill and empathy and humanity with which he would be able to convey this incredible experience.

Michael Slate: I really want to emphasize that as well. I was very, very moved by what emerged as the character of Mohamedou Ould Slahi. Let’s talk about Mohamedou a little bit more here. Because I want people to understand that you’re reading a book, and it’s just a guy taking a trip, and then all of a sudden he goes from just a guy on a plane, to a man who’s spent, like how many years—since 2002, he was brought to Guantánamo, but it was the end of 2001, when he was actually picked up in the beginning, and he’s been there ever since. So we’re looking at 13, 14 years trapped in this system. And yet he managed to write a book that was full of both a very good sense of the ironic and a good sense of the absurd. Many people who have looked at the book have referred to it as Kafkaesque and Dostoyevsky and all these people. He’s dealing with something that was just so intensely absurd, but intensely repressive and oppressive, and every day his life is on the line. And yet what comes through is a person who’s really trying to maintain his humanity and his sense of humor and his view of some kind of future.

Larry Siems: Yeah, that’s exactly right. In any form his first person testimony would have been extraordinary because his story is so extreme and extraordinary. But his book moves beyond personal testimony into a real realm of literature. I think it belongs on the shelf with some of the great writing about prisons and prison communities that has ever been created. Like you say, he maintains his humanity in the most dehumanized situation. He does it because he’s intensely interested in those around him. He’s curious and he’s empathetic. These are his two most obvious and compelling characteristics. He’s constantly drawn outside of himself by his environment. He’s driven by his curiosity to learn English, to master English. There’s a scene early on where he’s, as you say, he’s flown to Guantánamo on a flight with 34 other detainees, and he arrives there in August of 2002. They’ve had a 30-hour flight on a freezing cold airplane, shackled in uncomfortable positions. They’re hooded and earmuffed and all these things and they throw them into a truck and the guards are shouting all these orders at him in English, which at that point he doesn’t know very well: “Sit down! Shut up! Cross your legs!” And one guard says, “Do not talk!” and another guard says, “No talking!” And he thinks to himself, in the middle of the extreme discomfort and pain that he’s feeling, and there’s certainly fear—he thinks to himself, “Wow, they give the same order two different ways: “No talking,” “Do not talk,” that’s interesting.

He’s just the sort of man who is always looking at his larger environment. He’s fascinated by language; he’s fascinated by the characters of his captors. And the result is, this is not only the first really in-depth look at what it is like to experience the kind of treatment that Mohamedou experienced, but it’s also an extremely moving and upsetting, but also revealing look at what it’s like to be a person who’s put in a position of having to mete out this kind of treatment. The book is a tremendous reclamation of humanity, not only for somebody who’s tortured, but for those who were asked to torture him as well. You get these vivid portraits of guards and interrogators who we recognize as our brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, our sons and daughters. These are the men and women we’ve asked to carry out these really quite appalling and immoral and at times quite ridiculous programs. And you get a sense of the toll that it’s taken on them as well.

Michael Slate: Part of what I was really moved by—one, people should understand that when he set out to write this book, when he was picked up, he didn’t speak much English at all. And he wrote the entire book in English, which is quite a feat when you’re looking at just over a few years, and he learns English inside this hellhole.

Larry Siems: It’s an incredible achievement. He’s obviously a tremendously gifted person. He was already fluent—he was bilingual from childhood in French and Arabic, of course, because he grew up in Mauritania. He’s the ninth of twelve children of a rather poor family. His father was a camel trader. His family moved to Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania when he was a teenager, right about the time his father died. And Mohamedou, a favored son, and a son on whom the family pinned its hopes, its economic hopes and dreams. He won a scholarship when he was in high school to study electrical engineering in Germany. He had memorized the Koran as a child, so he obviously had great intellectual gifts. He went to Germany and earned an engineering degree, and lived and worked as an electrical engineer in Germany for most of the 1990s.

So then he was, of course, fluent in German. And then he lived briefly in Canada. I think he had some rudimentary English from a couple of months in Canada. And many Germans have quite good English. So he had a foundation of English, but it really was his contact with his guards and his interrogators that led to this incredible work that’s written in English. There’s something really telling about it. It’s not just a natural gift and fascination for language, but it’s also this real desire to communicate with and understand every single person that he came in contact with. Obviously learning the language of his guards and interrogators was an essential part of that process. He has just a fascinating and extremely admirable ethic as a writer and as a person. He treats everyone as an individual. He says we’re all a combination of good and bad. The question is what percentage of each. So he’s just constantly compelled to think about and examine the inner lives of the men and women who are shaping his destiny every single day.

Michael Slate: Let’s talk about a few of the particulars about his case. One of the things that really got me is, you look at this, and there had to be a tremendous risk in him doing this. What was the risk to Mohamedou for writing this book in the first place? He has to keep it in his cell wherever he is. He has to keep the things there. When people read the book, you understand that when these guards come in, they rip apart everything. They can take anything and everything from you, all at once. And the different personalities of the guards—they’re matched up to drive you kind of insane. What’s the risk to a person sitting in the middle of that writing a book like this? And I have to tell people, I’m going back through it a second time, and I’m really moved by what I read there, in terms of the treatment, both the inhumanity and the humanity that’s concentrated in the entire book. So, what’s the risk to Mohamedou in writing this book and getting it out like he is now?

Larry Siems: I think that’s a really interesting question. I hadn’t really thought about it in those terms. He wrote the book in 2005, at a time when the worst treatment had passed. His special project interrogation ended in 2004. At the time he was writing the book, and he writes really up to that present moment, it’s very clear that there’s a recognition on the part of the military authorities in Guantánamo that they have taken him to the brink, psychologically, physically. So there’s a real clear effort to rehabilitate him. He talks about a new team of guards that are assigned to him. Their job is to be nice to him and really specifically to help in his rehabilitation. One of those guards, very poignantly drags his mattress in front of Mohamedou’s cell, and they spend nights just talking to each other all night.

So he writes it during that period when I think there was a sense that the worst was behind him, so he was I think maybe breathing a little easier, and he had a chance to kind of reflect a little bit on his experience, and I’m sure that the writing process was an essential part of that recovery to some extent. So I never thought of it in terms of risk. I thought of it much more in terms of faith, what an incredible act of faith this is on his part: that if he just faithfully and honestly tells his story, and does it in a way that preserves and recovers his dignity and the dignity of some of the guards and interrogators—because remember, torture dehumanizes not just the tortured, but also the torturer—that if he does these things, and just does it accurately, that manuscript will eventually find its way to us. He addresses us, the American people directly: “What do you think, dear reader?” He says it several times in the book. If that manuscript just makes it to us, that there will be some movement, that this kind of crazy deadlock that exists in Guantánamo, that’s a combination of legal limbo and bad politics and just kind of delaying accountability for terrible mistakes will be broken.

I’m a lifelong advocate for freedom of expression and the power of writing, and for me, I was constantly inspired by that gesture of faith. He says, I’m going to tell my experience. I’m not going to exaggerate; I’m not going to understate it. I’m just going to tell you what I experienced. And just in doing that, and the faith that it would make it out of this kind of lock box that is Guantánamo and eventually be published and be received the way it’s been received, is so inspiring.

Michael Slate: Part of what got me is, here’s a man who went through being picked up, and actually driving down to the police station himself to go for questioning, and he ends up going through this incredibly horrible journey that involves detention, rendition, and finally ending up in prison in Guantánamo. He went through a number of places. He was in Mauritania, he was in Jordan, then from Jordan to Bagram, and then from Bagram to Guantánamo.

Everybody always talks about Jordan as, that’s a place where the big secret is, and it’s not so secret, that torture is going to be heinous.

Larry Siems: That’s again one of the really fascinating elements of the book, is that it isn’t just Guantánamo, but it’s kind of this odyssey through this secret network of intelligence prisons around the world. So there’s a kind of a comparative study of intelligence prisons and interrogation that goes on just implicitly within the book. As you say, he reported for questioning, voluntarily drove himself to the police station in November of 2001, was told that he would be home in a day or so. Instead, the Mauritanians held him just long enough for the U.S. to arrange for a Jordanian rendition flight to take him to this prison in Amman where he was held for about seven and a half months.

From a Human Rights Watch report, we know which prison that is, and we know he was one of about fifteen people who were renditioned to Jordan at this time period. That time period is before the CIA “black sites” had opened, so I think this was a period where the CIA was using proxy torturers and interrogators before it opened up its own secret operations.

What’s interesting is, he’s quite open in talking about the kinds of pressure that he was under in Jordan, but it was nowhere near the level and magnitude of abuse that he would suffer in Guantánamo. The Jordanians mostly—they were certainly torturing in the prison, and their pressure on him was essentially to make him listen to or hear or be in the proximity of that torture as a kind of pressure tactic. And then they would move him. He was a secret prisoner there, which meant that every time the International Committee of the Red Cross came to visit the intelligence prison, they moved him to the basement so that nobody would know he was there. This was enforced disappearance. He had been disappeared from the face of the earth. His family for a whole year thought he was still in the local prison in Mauritania, and they were delivering food and clothes to that prison. That’s in itself a gross human rights abuse that’s tantamount to torture because of the anxiety it causes the family, and the prisoner knowing how anxious the family must be not knowing where he is. So that was clearly a level of abuse that rose to torture in Jordan. But it was really this special project interrogation that happened in Guantánamo that is the most horrific onslaught that he faced anywhere.

Michael Slate: One of the high points of that is this mock execution. Can you talk about that a little?

Larry Siems: As I said before, these were things that were planned, written out in special interrogation plans that went through several drafts and were signed off on by the Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. They moved him into ever more extreme isolation, subjected him to ever more extreme sleep deprivation, until ultimately he was being interrogated by three shifts of interrogators for twenty out of twenty four hours every day. He was subjected to freezing cold rooms, sometimes nude, sometimes doused with water, shackled in stress positions, forced to listen to heavy metal music, strobe lights, many death threats against him, and ultimately a ruse in which they pretended that they had captured his mother and were going to bring her to Guantánamo. And then, as you say, this mock kidnapping and rendition. In the original draft, according to the Department of Justice’s 2008 report about FBI complaints about interrogations in Guantánamo, the original draft of his special project interrogation plan involved dragging him out of his cell, shackling him, binding him and putting him in a helicopter and flying him out over the Caribbean probably to threaten to kill him, and then pretend that they were taking him to a third country.

According to that report, the commandant of Guantánamo decided not to do that because too many people would know about it. And again, these were things that were really kept in close secrecy. There were only small units of the larger operation that even knew these things were happening. So instead what they did is they dragged him out of his cell with a kind of commando team, shackled him, hooded, blindfolded, and threw him in a motorboat and sent him out into the Caribbean with two interrogators, a Jordanian and an Egyptian interrogator, pretending that they were going to take him to one or the other of those countries, which he thought was quite funny. With his typical sense of irony and humor, he knows that he’d already been to Jordan. He’s already seen what they did. So it wasn’t such a terrifying thing. So they’re pretending that they’re taking him to one of these countries, and they’re beating him. They’re alternately beating him and filling his jumpsuit with ice in order to alleviate the swelling and bruising from the beating but also to induce close to hypothermia, or hypothermia. So they do this for several hours. The boat lands again, and they pretend again that they’re dragging him into some now other country’s prison. And all along he knows where he is, because they’ve been doing these things and the prisoners tell each other these stories. He said, “I knew all along that I was just being taken to a new place.” And that new place is an isolation hut that’s been prepared specifically for him. Everything is blacked out so no light can enter, and he remains there for several months. Well, he remains there in fact for several years, but they eventually open up the windows and it becomes a living space. But for several months, the interrogation, the sleep deprivation continues until he’s taken to the absolute extremes, and as he describes it very vividly in the book, he begins hearing voices, the voices of his family, sort of heavenly choruses of Koranic reading. And we know that this is true. It’s important to emphasize that everything that he tells about in his experience, the torture that he describes in Guantánamo is completely corroborated by the government’s own reports and documents that have been released.

In those documents, quite chillingly, is an email from one of his interrogators to an army psychologist saying, “Mohamedou is hearing voices now. Is that normal?” and the army psychologist writing back and saying, “Well, given the level of sensory deprivation, hallucinations are to be expected.”

Michael Slate: This is all happening to a man who has never been charged. A federal judge actually ordered his release from Guantánamo. But he still remains trapped in this hellhole. This is a very incredible predicament here.

Larry Siems: It is. And it’s a shameful predicament. In one sense this manuscript which he wrote in 2005 is just a very simple call for justice. And that call for justice was suppressed for seven years as part of a larger regime of secrecy that’s been imposed on him and on all the men who have been held in Guantánamo. That secrecy was purposeful. From the start it existed specifically in order to allow torture and other human right abuses to happen. Then it was prolonged in order to hide the fact that that abuse had happened, and ultimately to forestall accountability for those abuses. To think that the failure to deliver justice, or to even make a case for why they’re holding this man for all of these years—the fact that some of that failure may actually have been just part of an effort to conceal what was done to him, to hide the crimes that were committed to him, to his person, that should disturb every American. This is now almost ten years after he wrote the manuscript, and the questions of why Mohamedou is in Guantánamo should have been answered long ago. The American people should ask the government to answer those questions. They’ve been answered, as you say, in a habeas corpus proceeding which resulted in a judge concluding that the government has no case against him. He’s never been charged. So he should be released.

Michael Slate: When people read this, and hopefully a lot of people are going to read this—you got a manuscript, and when you talk about redacted, I want people to understand that on every page almost, there’s these thick black lines blocking out text. And in some cases, there’s like five pages all at once that are all just blacked out. Even the simplest male or female pronoun is blacked out. Looking at that, I kept wondering, how the hell did Larry work with this to actually retain the beauty and the power of the book? It’s really disturbing when you read this and you just see blocks of text blacked out.

Larry Siems: You’re right. These are the fingerprints of the censorship regime that continues to exist in this place. To this day, no writer or journalist has ever spoken to, or communicated directly with, a Guantánamo prisoner. A large part of that is to keep the prisoners from telling their stories, from becoming human, human faces and human biographies, for the American people. What’s amazing is how much we get in this book. So, yes, the redactions were a stumbling block and obstacles in a lot of places, but what you get is this voice, this approach, this experience, this way of interpreting and presenting experience, this real writer’s sense of form and beauty and character and all of these things. They are vivid, even with the redactions.

So for me the process was just following that voice, listening to that voice, following the clues, learning that that voice was always trustworthy. Even for me, throughout the year I came to appreciate ever more, at every turn, how just accurate and truthful and fully realized his narrative was. So I sort of followed his lead on it. And then I had alongside of it, like I said, dozens if not hundreds of pages of government documents that align exactly with his story. So some of those redactions, you get a sense of what’s behind those redactions because the same information exists in other documents. The story that he tells in this book, he also tells in some form, much shorter, to these two review boards in Guantánamo in 2004 and 2005. Interestingly in 2005 when he’s beginning—this is the first time that he’s recounted his abuse. In 2004, which is just after the abuse ended, he was clearly terrified to talk about it. They’re asking him if he’s been abused, and he said, “You know, I really don’t want to talk about that.”

In 2005, he starts to tell the story to the review board, and just when he’s getting to the part where he’s sexually assaulted by these two female interrogators, and then describes leading up to this kidnapping that we talked about, the transcript in bold-face type says, “At this point the recording equipment malfunctioned,” and they offer a kind of cursory summary of what must have been many, many minutes of him telling this terrible, harrowing story.

So this is a story that has been suppressed and suppressed and suppressed again. But for me, like I say, when I got this manuscript in 2012, much of that story had already been public knowledge because of the declassification of the documents. But what we had never had was a voice like this that could help us understand so clearly what this means. And that voice triumphs even over the redactions in the manuscript itself.

Larry Siems: I agree 100%.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.