Case #77: Christopher Columbus Brought Genocide and Slavery to the "New World," and America Celebrates Him for It

October 10, 2016 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian recently wrote that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

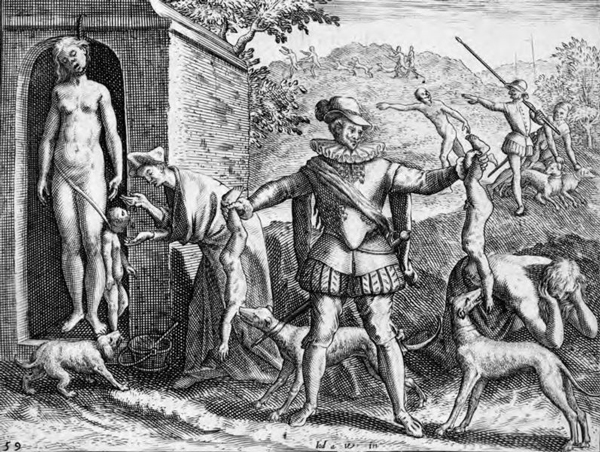

Spaniards killing women and children and feeding their remains to dogs. Illustration based on eyewitness account by Bartolomé de las Casas, in his book published in the 16th century.

THE CRIME: On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus, an Italian sailing for Spain, landed on what is now the Bermuda Islands. Columbus is celebrated in the U.S. as the person who first “discovered” the “New World,” making it possible for those who came after him, through hard work, to create the greatest global power in the world today, as the official declaration of “Columbus Day” as a national holiday would have you believe.

Columbus did not “discover” the Americas—they had been inhabited by many different indigenous peoples for some 13,000 years. But he did bring conquest and enslavement, and launched one of the most massive, horrific genocides in human history.

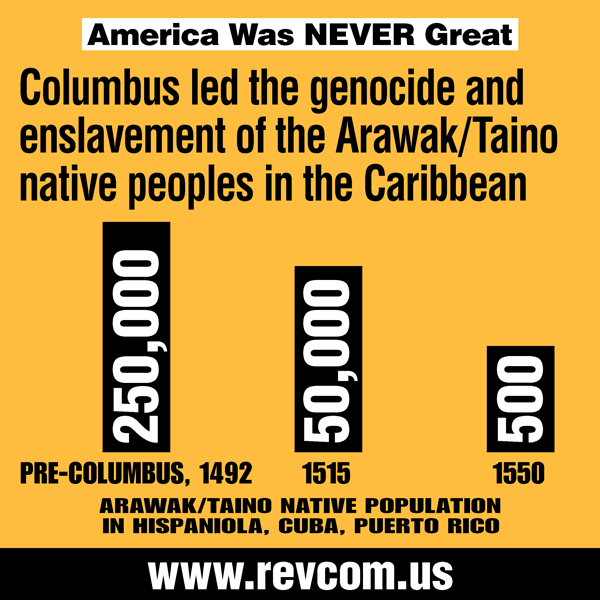

Columbus was searching for a shorter route to the East Indies (South and Southeast Asia), in pursuit of gold and new peoples to exploit and convert to Christianity, and initially thought that's what he'd found. He and his crew were first met by the indigenous Arawaks, who swam out to welcome them. At the time, it’s estimated that roughly 250,000 Arawaks inhabited the nearby island Columbus named “Hispaniola”—today's Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. The Arawaks lived in communal, agricultural villages, without horses, iron implements—or prisons or prisoners. Columbus wrote they “are so naïve and so free with their possessions that no one who has not witnessed them would believe it. When you ask for something they have, they never say no. To the contrary, they offer to share with anyone....”

But Columbus was making his own calculations from the moment he encountered them: “They willingly traded everything they owned.... They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features.... They do not bear arms, and do not know them.... They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane.... They would make fine servants.... With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

He immediately took several Arawaks captive, demanding they lead him to the source of the gold on the tiny ornaments they wore. Discovering gold was the reason the Spanish king and queen had backed his voyage. In return, Columbus was to receive 10 percent of all the wealth he brought back, and be appointed governor over the colonized territories. Columbus soon sailed to Cuba and then to nearby Hispaniola where, “bits of visible gold in the rivers, and a gold mask presented to Columbus by a local Indian chief, led to wild visions of gold fields,” Howard Zinn wrote in A People’s History of the United States.

On Hispaniola, the Spanish built a fort (the 39 sailors left to find gold were later killed by the Arawaks). Meanwhile, Columbus took 15 captured Arawak Indians back to Spain. He presented them to the king and queen as evidence, along with exaggerated claims of massive gold mines, that he should be given backing to return with more vessels and troops. Columbus promised he would bring back “as much gold as they need... and as many slaves as they ask.”

Based on these promises, in 1493 Columbus went back to the Caribbean islands with 17 ships and over 1,200 men. From his base on Hispaniola, Columbus sent out expeditions from island to island, capturing Indians and searching for gold fields. Finding none, and needing to fill their ships for the return voyage, in 1495 Columbus sent an expedition that, as Zinn writes, “went on a great slave raid, rounded up fifteen hundred Arawak men, women, and children, put them in pens guarded by Spaniards and dogs, then picked the five hundred best specimens to load onto ships.” Two hundred died crossing the ocean; those who survived were sold in Spain to be used by artisans and as domestics.

But with too many slaves dying in captivity, and having to make good on his promise of gold to the Crown and the Church, in Haiti all persons 14 years or older were forced to work in gold mines until exhausted. It’s estimated that within eight months, nearly a third died. Each had to collect at least a thimble of gold dust every three months. This was a nearly impossible task: the only gold to be found were bits visible in some rivers. As many as 10,000 had their hands cut off and tied around their necks while they bled to death for failing to meet their quota. Others fled and were hunted down with dogs and killed.

Once the Spaniards figured out there were no gold fields, they forced the indigenous people into slave labor on huge feudal agricultural estates called encomiendas, where they were worked to death.

The Arawaks tried to organize resistance, but were no match for the Spanish armaments. Those captured were hanged or burned to death, triggering the start of mass suicides among the Arawaks, including babies deliberately poisoned by their mothers rather than see them tortured. In two years, half of the 250,000 indigenous people in Haiti were dead. By 1515, only 50,000 Arawaks remained; by 1550, there were 500. And this was just the beginning of the massive genocide of native peoples in the Americas by European powers and their colonial settlers, set in motion by Christopher Columbus and his “discovery.”

The atrocities committed by the Spaniards were so gruesome they’re hard to imagine. Bartolomé de las Casas, a former slave owner who became bishop of Chiapas, described some of what he witnessed in his book History of the Indies. The Spanish “thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices of them to test the sharpness of their blades.... Two of these so-called Christians met two Indian boys one day, each carrying a parrot; they took the parrots and for fun beheaded the boys.” Las Casa concluded: “Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight as no age can parallel. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature that now I tremble as I write.”

The Criminals:

Christopher Columbus: Columbus made four voyages to the West Indies, and he was the first to engage in savagery, slavery, and to commit genocide in the New World. Among his many crimes, Columbus supervised the selling of native girls—the ages nine and 10 were most desired by his men—into sexual slavery. He forced the native peoples to work in the gold mines until they died of exhaustion, killing anyone who resisted. Catholic law forbade enslaving Christians; so Columbus refused to baptize the people of Hispaniola. If the Spaniards ran short of meat for their dogs, Arawak babies were killed for dog food.

On his third voyage in 1498, Columbus landed on the island of Trinidad and explored the area off the north coast of South America, before returning to the Spanish colony in Hispaniola. Columbus’s reputation, and that of his two brothers, was so horrific that they were arrested by the governor and shipped back to Spain in chains in 1500. But because of his great assistance to the Crown, Columbus was pardoned by the King and Queen of Spain and let go.

King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain: By continually financing the crimes of Columbus, they enabled the brutality, exploitation, and enslavement to expand continually. For them this was a profitable investment, but not only that. It served the goals of the Catholic Church, which were to expand the conversion of souls to Christianity—in opposition to Islam—around the world.

Pope Alexander VI and the Catholic Church: In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal Bull (or decree)—Inter caetera—which declared the full backing of the Catholic Church to Columbus and the Spanish king and queen and all they were doing in the New World. Inter caetera granted official ownership of the New World—“dominion”—to Ferdinand and Isabella. It instructed them to “civilize” every “savage” they encountered. In 1515, an ultimatum was issued by the Spanish conquerors to all indigenous people they encountered in the New World to accept “the Church as the Ruler and Superior of the whole world” or else:

We shall take you and your wives and your children, and shall make slaves of them, and as such shall sell and dispose of them as their Highnesses may command, and we shall take away your goods, and shall do all the mischief and damage that we can.

The Alibi:

The Spanish expeditions to the “New World” were justified by Spain’s rulers and the Catholic Church as expressions of the “will of god”—to convert “savages” to Christianity. As Columbus described it: “Thus the eternal God, our Lord, gives victory to those who follow His way over apparent impossibilities.”

The Actual Motive:

The goal of the expeditions to the Americas was to find new sources of wealth, especially gold, and people who could be enslaved to produce products for an emerging market. In competition with the Ottoman Turks, who had blocked access to Asia, the Catholic Church and the European powers under their influence were searching for access to new markets, and new sources of gold and other wealth. Columbus offered the promise that there was a way to those riches by crossing the ocean to the west. Finding a continent of people not yet discovered by other rival powers, who could be conquered, dominated, exploited, and converted to Christianity, was the answer to a prayer.

Repeat Offenders:

The Spanish empire eventually expanded across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of Central America, and much of Mexico and North America. Meanwhile, in 1501-1502, a Portuguese colonizing expedition sailed along the coast of South America, including the bay of present-day Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. From these origins and foundations, and later British and French colonization, what would become the United States of America arose, developed, and carried forward what was begun by Columbus. The genocide of Native Americans began before and continued after the official founding of this country. So did the enslavement and murder of millions and millions of African people, who were first brought to Virginia in 1619, and on whose backs the wealth of this country, and many other parts of the world, was built.

Sources:

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, Harper & Row, 1980 (first edition)

Bartolomé de las Casas, History of the Indies, written 1527-1561, published by Harper & Row, 1971

Eric Kasem, “Columbus Day? True Legacy: Cruelty and Slavery,” Huffington Post, October 15, 2015

Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, Vintage Books, 2006

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.