Interview with Simon Moya-Smith about Standing Rock

“Taking it back to the beginning – another example of Native Americans fighting for our rights as human beings.”

October 17, 2016 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Revolution Interview

A special feature of Revolution to acquaint our readers with the views of

significant figures in art, theater, music and literature, science, sports and politics. The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our paper.

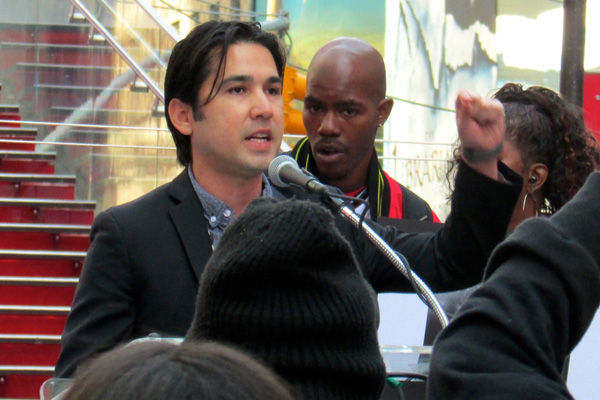

Simon Moya-Smith is a Native American journalist and activist. Revolution spoke with him as he was returning to Standing Rock, where he has been part of the battle to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline that endangers the water supply and encroaches on land that is precious to the traditions of the Native people in the area.

Above: Simon Moya-Smith representing for Mah-hi-vist Goodblanket, 18, who was killed by Custer County Oklahoma sheriffs on December 21, 2013. Photo is from Rise Up October, NYC, October 22, 2015. Photo: revcom.us.

Q: I want to get into what’s happening on the ground right now at Standing Rock, but also get your insights into the context for and significance of this struggle, both for Native peoples but also for humanity and the environment.

A: Taking it back to the beginning, this is yet another example of Native Americans fighting for our rights as human beings. Our allies have joined the Native American struggle against the aggressive settler-colonialism of the 21st Century, recognizing that water is the first medicine. When you get sick, what do you do? You take ice chips. Or when you’re sick, you get an IV. Hydration is key. So what you’re seeing now with all these arrests are invaders arresting indigenous peoples and our allies for protecting our land, and our water, and future generations.

What we know about pipelines is they do leak. That’s the basics of it, right? That’s why plumbers exist, because pipes will leak. And these pipes are definitely dangerous because they’re close to a water source, the Missouri River, which is the main water source for the Standing Rock people. And the sense that people have out there is one of, we are our great-grandparents' kids—the ones who went through the boarding school systems, the ones who went through their own form of resistance in their day, against the oppression that they felt. They had to stand up and do something. Just like in the 1970s with the Wounded Knee occupation over there at Pine Ridge. This feels similar to that, in that once again, here we are, fighting for our rights as human beings. And we’re extremely happy that we have celebrities like Shailene Woodley there. Yesterday, Dave Mathews went up there. People are realizing that the Native American is still being threatened by the descendants of people who sought to exterminate us and steal our land.

Q: The Army Corps of Engineers put out a statement “asking” the pipeline builders to pause construction at Standing Rock. Can you speak to that?

A: Sure. The Army Corps of Engineers is asking, they’re requesting, that the Dakota Access Pipeline be halted. These are not injunctions. These are requests. They’re just asking. And if they don’t stop, there’s no repercussions. So why would they stop? That’s the problem, they’re making a request. You’re asking these people to stop building the pipeline and you know they are not going to do that. So what are you trying to do? What message are you sending by just asking the company to stop it when you know they won’t? Those are hollow words. It’s like asking a dog that’s biting, speaking of dogs, right, to release when you know it won’t.

Q: If I understand what you’re saying, this allows the U.S. government to appear benevolent and neutral...

A: Sure, right? Exactly. They’re trying to make it appear they’re on the side of Native Americans while maintaining a position of safe impartiality.

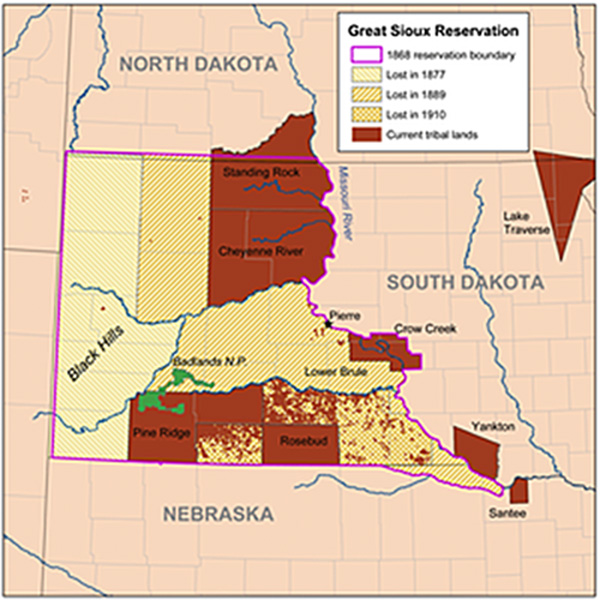

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie supposedly guaranteed Native people the right to certain lands. But as oil and minerals were discovered, the lands were grabbed back by the U.S. government.

Q: I understand Standing Rock is part of a much larger area the U.S. government promised to Native peoples.

Q: What you’re talking about is the Fort Laramie Treaty. The Fort Laramie Treaty was after the westward expansion and encroachment by white invaders. Not settlers! Remember, it does violate a fundamental law of physics to call them settlers before you call them invaders. You first have to invade before you can settle. What they did, they invaded. So it’s not incorrect to refer to European encroachment as an invasion. So there was a European invasion headed our way.

So once they started to settle this area, there was an agreement with a number of Native American tribes and nations, I think it was five that signed the treaty. And the treaty essentially said, “This territory is yours, you don’t have to worry about white people ever coming in here or trying to take your territory.”

But then it continued to shrink. It continued to shrink because there was no comprehension of oil and mineral extraction when reservations were set up. Some reservations were put on oil or mineral-rich land. And then the United States went and found that out, and it was like “Jesus, we have these treaties with the Indians, but there’s a lot of fucking oil under there. How are we gonna get that out? We have to move them off the reservations. Maybe we can squeeze them into cities.”

So, in the 1950s they had the Indian Relocation Act. The Indian Relocation Act wasn’t removal. Removal was removing Native Americans from their territory, like in the Trail of Tears. But relocation was trying to get Indians off reservations into cities. Give them a little dough so they can go to vocational schools. And it didn’t work out it that well. It was culture shock for a lot of Native Americans. They came from living in these rural environments, living with their own people, to urban environments where there were no other Native Americans other than ones relocated from reservations.

I’m a descendant of the relocation era. My grandmother moved from the Pine Ridge reservation to Denver. So, I was born in Denver. But I’m a descendant of the relocation era.

Q: Talk about this pattern of the U.S. government ripping up and violating treaties with Native peoples when resources were found under their land.

A: Look up the Elouise Cobell settlement. She has since passed. But she sued the United States government because she believed they were mis-managing funds from resources on their reservation. And there was finally a settlement by the United States government in favor of Elouise Cobell [editors’ note: Elouise Cobell was lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit filed in 1996 against the U.S. government for illegally stealing billions of dollars of resources including timber, minerals and oil, from Native American reservations]. More Native Americans are recognizing they are not getting their cut of extraction of natural resources coming out of reservations.

Now, there is extraction when Native Americans say there shouldn’t be extraction. Which brings us back to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Even though they’re not drilling on Native American territory, they are desecrating our land and cutting through a sacred site. And this brings us back to treaty violations, as we mentioned before. The Fort Laramie Treaty. You wrote down on a piece of paper You’re mucking up the legal jargon so you can violate the treaty—convoluting something as simple as you don’t violate treaty.

They don’t violate treaties with France, or Russia. But they violate treaties with Native Americans because we don’t have an army. We don’t trade with them, they just take. They do what they wanted to do, and we’ve been standing in opposition to this form of aggressive theft for centuries.

Q: It seems there is an important convergence at Standing Rock of thousands of people, putting their bodies on the line, taking a stand there, right? Not a beginning, as you say, but a resurgence of struggle with significance both for the struggle against genocide against Native peoples but also for the survival of the planet.

A: Yeah. It’s true. When I was at Standing Rock, I was just sitting by my car, and I see a group of Samoans, actually, come by. They’re looking around, they didn’t know where to go, so I waved at them, “Hello! Hello!” They were sweet and wonderful people. They just needed directions, right? So I directed them to the tent, and they can speak with the elders over there.

And if you look, it’s not just indigenous people even though indigenous people are converging. Ecuadorians came. Hawai’ians had come. Indigenous peoples are converging. But also other people. You’ve got Irish, English, Scottish contingents. They are indigenous to their land, and they have to drink water, you had people coming that are indigenous not to this land but to their land, and they know water is important for them.

You were mentioning, here in the United States, a collection of so many different nations. You have the Crow, you’ve got the Oglala, so many nations coming into one territory, like what we did when we kicked the shit out of Custer. We had to do that, you know. We came together as nations. We were like, OK, here comes the army. We’re all Indians to them. They want to kill you, so we have to take this guy [Custer] out.

Now you have a collection of so many nations on the camp itself. You have banners and flags, that represent many nations. You can look over to your left, and over here are the Crow, over here the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, the Oglala Lakota over there, the Sicangu Lakota across the river, coming together because we have faced the same aggressive settler-colonialist aggression for centuries. They don’t discriminate—even today, people look at Native Americans as one big fucking group—everybody has a headdress, everybody has long hair and braids. Even though if look to the north, you see our relatives in Alaska, they look nothing like the Oglala. The Oglala look nothing like the Seminole. We’re all separate, sovereign, indigenous people that are based in a certain locale. The Ute are mountain people. The Ojibwa are forest people. The Oglala are the plains people. The Tulalip in the Pacific Northwest, they’re the ocean people. We’re all very different in our languages, our culture, spirituality. But when it comes down to this, we’re all facing the same goddamn threat. They’re well aware that it could be only a matter of time before a pipeline wants to cut through their land, and they’re going to try to justify it in the same way.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.