Case #71: The Colfax Massacre of 1873... and the Supreme Court Stamp of Approval for Racist Terror

November 28, 2016 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

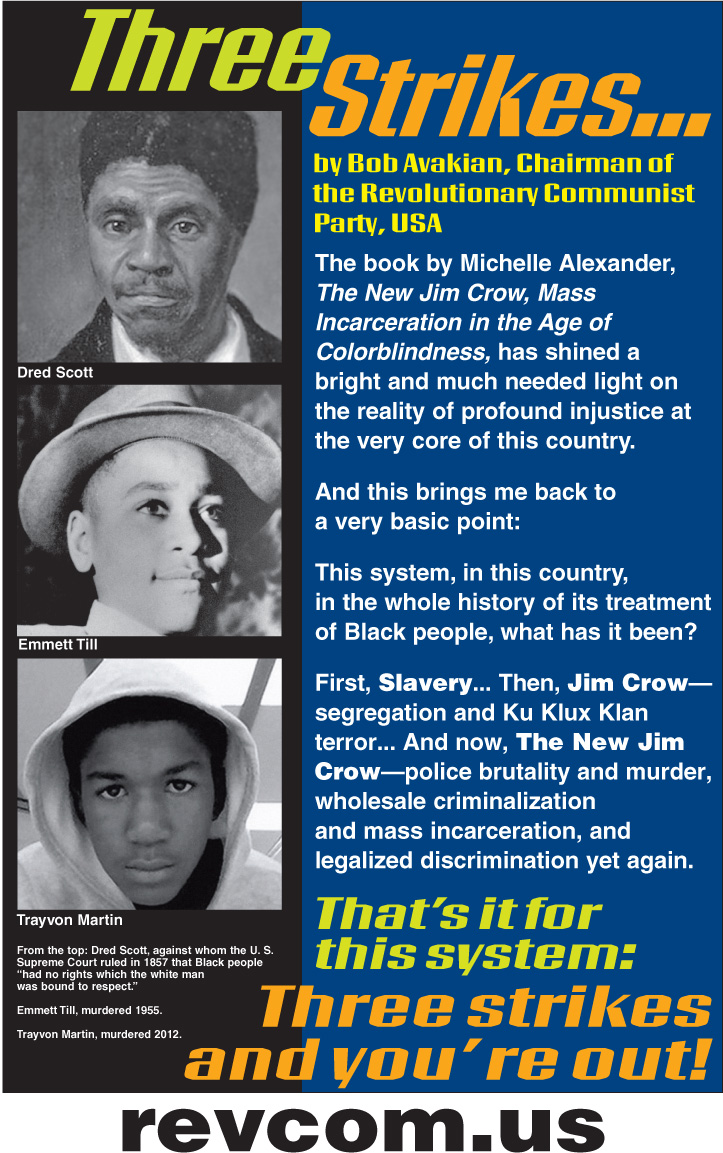

Bob Avakian recently wrote that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

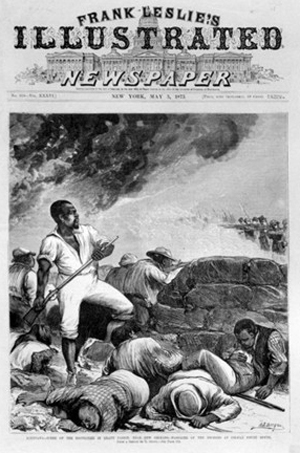

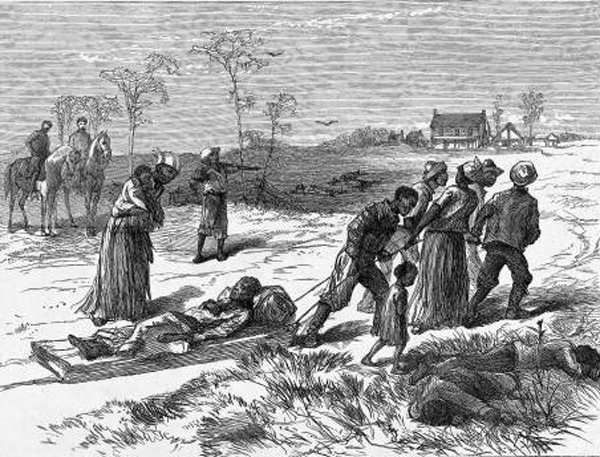

In 1873, Black people demanding their right to vote in Colfax County, Louisiana were attacked by armed white supremacist mobs. There was a courageous attempt by Blacks to defend themselves but they were massacred. Above, a magazine in New York reported on the crime.

On April 13, 1873, Easter Sunday, a mass slaughter of Black people occurred in Colfax, Louisiana. Over 300 heavily armed white men, most of them former officers and soldiers in the Confederate Army, shot, stabbed, burned, and maimed Black people seeking shelter in a courthouse. Many were killed as they tried to surrender. Historian Eric Foner described the Colfax massacre as the “bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era.”

Reconstruction was a brief, more or less 12-year period after the end of the U.S. Civil War. As Bob Avakian wrote:

[D]uring the brief period of Reconstruction, while the full promise of these rights was never realized, there were significant changes and improvements in the lives of Black people in the South. The right to vote and to hold office, and some of the other Constitutional rights that are supposed to apply to the citizens of the U.S., were partly, if not fully, realized by former slaves during Reconstruction. And in fact some Black people were elected to high office, though never the highest office of governor, in a number of southern states.

This was very sharply contradictory. The armed force of the state, as embodied in the federal army, was never consistently applied to guarantee these rights, and in fact it was often used to suppress popular struggles aimed at realizing these rights. But there was a kind of a bourgeois-democratic upsurge in the South during this period, and it not only involved the masses of Black people but also many poor white people and even some middle class white people in the South. During these ten years of Reconstruction, with all the sharp contradictions involved, there was a real upsurge and sort of flowering of bourgeois-democratic reforms. This was not the proletarian revolution, but at that time it was very significant. (From “How This System Has Betrayed Black People: Crucial Turning Points,” on revcom.us as part of a series of excerpts from Bob Avakian’s writings on the Black national question.)

THE CRIME: From the beginning, these developments were assailed with convulsions of mass terror and violence across the entire area of the former Confederacy. White supremacists were determined to reinstitute a system in which gains Black people had made were violently snatched away, and Black people were ruthlessly repressed. Schools were burned, entire communities destroyed. The Ku Klux Klan was founded and grew dramatically in these years, carrying out lynchings, night raids, and terroristic assaults upon newly freed Black people across the South.

This violence permeated every aspect of society and was intended to enforce a culture of white supremacy. Historian Eric Foner wrote, “...(V)iolence was directed at... ‘impudent negroes’—those who no longer adhered to patterns of behavior demanded under slavery. A North Carolina freedman related how, after he was whipped, his Klan assailants ‘told me the law. That whenever I met a white person, no matter who he was, whether he was poor or rich, I was to take off my hat.’” Robert Smalls, a former slave who became a U.S. Congressman from South Carolina until 1887, said when he left office that “fifty-three thousand African Americans had been murdered, mostly in the South, in the years since emancipation,” according to historian Douglas R. Egerton.

Louisiana was a particularly violent inferno of racist mob violence against newly enfranchised Black people. In September 1868 over 200 people were murdered in three days in St. Landry Parish. Later that month, hundreds of whites unleashed a bloodbath in Bossier Parish, and by October, 168 Black people there were dead.

In Colfax, federal investigators arrived two days after the massacre. They found too many mutilated corpses on the courthouse grounds for them to count. Most had been horribly tortured and shot in the back of the head at close range. Historian Charles Lane described some of what the investigators literally stumbled over: “One lay dead with his throat slashed. Another, stripped to the waist, had been so badly beaten that no facial features were recognizable; next to him lay the broken stock of a double-barreled shotgun. All that remained of the courthouse were its singed brick walls, reeking of smoke. In the ruins, the officials found a human skeleton.” The number of dead is unknown; most estimates say at least 150 people were murdered that day.

No state charges were brought against any of the murderers. Federal charges were brought against dozens of members of the white-supremacist mob. They were not charged with murder, only with violating federal laws against interfering with people’s “right and privilege peaceably to assemble together.” In federal trials, only three men were convicted of any crime at all. The convictions were appealed, and set aside in federal district court. Federal prosecutors appealed that decision to the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case U.S. v. Cruikshank (William J. Cruikshank was one of the three men convicted of violating Federal civil rights law).

A drawing from Harper's Weekly depicting Black people collecting the bodies of the murdered after the massacre.

The Supreme Court heard the case in 1875. By that time, federal troops to enforce Reconstruction remained in only three Southern states—Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. The other states had been, in the language of white supremacy, “redeemed”: white supremacy had begun to be restored in all the laws and institutions, and the odious system of Jim Crow was becoming entrenched.

The Court overturned the guilty verdicts on the three racist killers. The essence of the ruling was that federal law cannot protect Black people from violations of their civil rights (or from mass murder!) committed by mobs, only violations of those rights by government agencies.

The legacy of Colfax and the Cruikshank ruling stood for over a century. Only in 2005—yes, 2005—did the U.S. government in any way acknowledge its endorsement of the murder and terror against Black people, when the Senate passed a resolution expressing its “remorse” for never having passed an anti-lynching bill.

In 1877 the U.S. withdrew the remaining federal troops from Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. This withdrawal, and the Supreme Court decisions, put an end to Reconstruction.

As Bob Avakian wrote:

[H]ere was a situation involving a major turning point in U.S. history where the question was posed very decisively: Can Black people and will Black people actually be “absorbed,” or integrated, or assimilated into this society on a basis of equality? Will not only slavery, but the after-effects of slavery, be systematically addressed, attacked and uprooted...or not? And the answer came thunderously through—NO!—this will not be done. And there was a material reason for that: it could not be done by the bourgeoisie without tearing to shreds their whole system.

Instead they re-chained Black people—not in literal chains, but in economic chains of debt and other forms of economic exploitation and chains of both legal and extra-legal oppression and terror. So this was one major turning point where the system fundamentally failed and betrayed Black people.

The Criminals

* The entire racist mob of unrepentant Confederate soldiers who committed the mass murder.

* The organizers and leaders of the lynch mob, Alphonse Cazabat and Christopher Columbus Nash, former Confederate officers who claimed to be the elected judge and sheriff of Grant Parish, where Colfax was located. William Cruikshank, a wealthy former slave plantation owner who participated in and helped organize the lynch mob.

* The U.S. Supreme Court. The Cruikshank ruling was a stamp of approval for the KKK and racist mobs to carry out terror and lynching. And the Supreme Court made the point again a few years later, invoking the Cruikshank ruling in another case concerning a lynch mob in Tennessee. The Court ruled that “Lynching was found not to be a federal matter, because the mob consisted only of private individuals.”

These rulings gave a green light to 100 years of lynch mob terror in the South. In the words of W.E.B. DuBois, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

Criminal Past

Many of the participants in the mass murder had owned other human beings of African descent. They had participated in driving them brutally on highly profitable slave plantations, whipping them, hunting them down. Some of them made fortunes buying, selling, and exploiting enslaved Black people. Most of them fought in a war to preserve the slave system. After they lost that war, all of them fought for years to restore and entrench white supremacy.

The Alibi

The white mob claimed they attacked Black people who were seeking shelter in the Grant Parish courthouse because they were about to kill and rape white people. They also claimed Black people were “stealing” an election so they could carry out further murder and rape. One participant in the lynch mob said, “the Negroes at Colfax shouted daily... that they intended killing every white man and boy, keeping only the young women to raise from them a new breed. On their part, if successful, you may safely expect that neither age, nor sex, nor helpless infancy will be spared.”

The Actual Motive

The small army that assaulted the Colfax courthouse had the explicit aim of restoring unquestioned white supremacy.

The motive behind their acquittal, and the Supreme Court decision in Cruikshank, represented the interests of even more powerful forces. As summed up in a special issue of Revolution, “The Oppression of Black People, The Crimes of This System and the Revolution We Need”:

[T]he true interests of the northern capitalists [in the Civil War] came out with their betrayal of Reconstruction. During this all too brief period of Reconstruction, in the 10 years or so after the end of the Civil War, the U.S. government had kept some of its promises and stationed troops in the South. These troops were there to prevent wholesale slaughters of Black people, and poor whites, who were striving to gain land and exercise political rights promised to them. But the capitalist class which now dominated the national government did this in large part in order to fully subordinate the former plantation owners; and when the ex-slaves and their allies fought “too hard” for their rights these same troops would be used against them.

Above all the northern capitalists wanted order and stability to carry out the further consolidation of their rule, as well as further expansion on the North American continent and internationally. The ferment and upheaval that would have gone along with everything that would have been involved in the former slaves playing a significant role in the political process or even exercising basic rights might have “sent the wrong message” to other oppressed people within the U.S.; and in fact, when in 1877 the U.S. troops were pulled out of the South, signaling the end of Reconstruction, they were immediately sent west—to fully crush the resistance of the Indians—and into the cities of the North—to violently suppress revolts of immigrant workers. Further, real freedom for the former slaves would have enabled them to resist the severe exploitation that was visited upon them, and thus would have made the re-integration of the southern economy into the larger society much less profitable for the ruling capitalists. So the Ku Klux Klan was unleashed in full force and played a brutal role in defeating and subjugating the freed slaves and progressive whites, often in bloody battles.

Ongoing Crimes

Louisiana converted its largest slave plantation, not far from the site of the Colfax massacre, into the notorious Angola prison camp. Louisiana now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world; its prison population is overwhelmingly Black men.

In 1950, the state of Louisiana put up a highway marker near the site of the Colfax massacre that perpetuated the justification, deceit, and cover-up of the mass slaughter of Black people there. It read, “On this site occurred the Colfax Riot, in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag [i.e., Northern anti-slavery] misrule in the South.”

Sources

“How This System Has Betrayed Black People: Crucial Turning Points,” on revcom as part of a series of excerpts from Bob Avakian’s writings on the Black national question.

The Oppression of Black People, The Crimes of This System and the Revolution We Need (Special issue of Revolution, October 2008)

LeeAnna Keith, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Douglas R. Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction (Bloomsbury Press, 2014)

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877 (DIANE Publishing Company, 2008; updated edition, Harper Perennial, 2014)

Peter Irons, A People’s History of the Supreme Court (revised edition, Penguin Random House, 2006)

Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction (Holt Paperbacks, 2008)

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.