Case #67

1848-1900: Brutal Exploitation and Ruthless Oppression of Chinese Immigrants

February 13, 2017 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian recently wrote that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

The Crime

Between 1850 and 1900, Chinese immigrants were super-exploited in the mines, fields, and railways, and were subjected to savage discrimination and repression, including lynch-mob pogroms.

Beginning in 1848, immediately after invading and seizing over half of Mexico’s land, including the entire state of California, American capitalists began to lure Chinese immigrants to fill their huge thirst for cheap labor for their westward expansion, which was fueled by the California gold rush, and to build the transcontinental railroad. These (nearly all male) immigrants were worked like pack animals in horrific conditions from dusk to dawn and in extreme weather. They were crammed into tiny tents, and were fed and slept on wooden cots. In one incident, when the workers went on strike, the company cut off all food supplies to the remote work camps and starved them for a week.

The role of Chinese immigrants in building the railroads is a story of its own—truly an incredible feat of human sacrifice and inhuman suffering. They shoveled, chipped and drilled holes for explosives, and scrambled up the lines while gunpowder exploded below them along the granite mountain surface. They labored through 60-foot snowdrifts, tunneling, blasting and laying railway tracks. Chinese women were mainly prevented from immigrating unless they could prove they were of “good character” (that is, were not prostitutes), yet some were brought into the U.S. (or bought or kidnapped) to be exactly that.

When Chinese immigrants died in America, it was a common practice for their ashes or bones to be sent back to the villages they had come from in China. In 1870, one newspaper reported that 20,000 pounds of bones had been gathered from shallow graves along roadbeds. These were from the bodies of about 1,200 Chinese workers—some of the thousands of Chinese immigrants who died building the railroads.

To pay for passage to America’s “Gold Mountain,” peasant families in China went into debt. Those unable to acquire loans would get “credit tickets”—money advanced by American employers to cover the voyage but which had to be paid back by wages earned over months or even years slaving away in the U.S., as indentured servants.

Railroad companies sent recruiters to China to bring back thousands of workers. Chinese immigrants were crowded into wretched hulls of ships crossing the Pacific Ocean, packed in like cattle with as many as 500 crowded into one hull, and where as many as one-fifth of them died on the voyage.

Corpses of victims of the largest mass lynching in U.S. history, when a white mob of 500 tortured and murdered 17-20 Chinese in downtown Los Angeles, 1871.

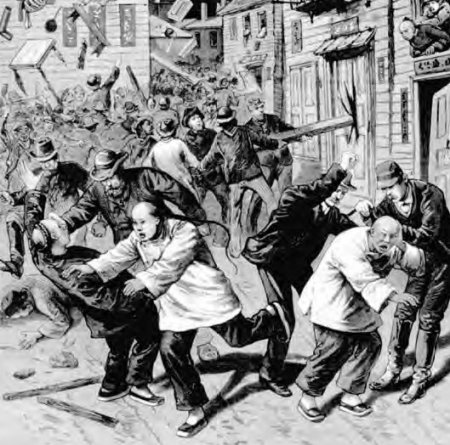

Newspaper illustration of anti-Chinese rioting in Denver, Colorado, 1880.

Newspaper illustration of anti-Chinese rioting in Denver, Colorado, 1880.

After the gold rush and railroad construction peaked, Chinese immigrants were shifted into the cheap labor pool for the expansion and growth of many other U.S. industries—reclaiming marshes and swamps for California’s agriculture, fishing and canneries, manufacturing (shoes, garments, cigars, etc.), as farmworkers and more. This super-exploitation was a tremendous source of the wealth that contributed greatly to building the U.S. economy in the latter decades of the 19th century.

To enforce this super-exploitation and maintain white supremacy for over half a century (1850-1900), Chinese immigrants in the U.S. were denied the most basic rights and were subjected to officially sanctioned racist violence and terror that rose to fever pitches during the economic depressions of the late 1870s and 1890s.

The infamous Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first law enacted by Congress to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S. It prevented Chinese in the U.S. from re-entering without certificates. It barred Chinese residents in the U.S. from acquiring citizenship. This official denial of rights opened the door to all other forms of legal and political attacks on them. It meant families permanently separated. The mainly Chinese male immigrant population could not bring over family members, even a spouse, and also were not allowed to marry whites. This cruel act was not repealed until 1943, and Chinese and other race-based quotas for immigration was U.S. law until 1965.

Scores of municipal, state and federal laws were passed between the mid-1800s and early 1900s that targeted Chinese. There were racist, xenophobic laws that made Chinese ineligible to testify against whites, even for murder. This legally protected white vigilante killers from prosecution.

There were laws that prohibited Chinese from attending public schools, owning real estate or getting business licenses and government contracts; that legalized a California state holiday to allow public anti-Chinese demonstrations; that limited Chinese who could arrive on one ship to 15; that prohibited Chinese the right to bail and habeas corpus; that prevented the hiring of Chinese or forced them out of work in industries they were driven into after the gold rush and railroad completion.

The laws and official attacks unleashed xenophobic mob violence. Gangs of whites stormed through segregated Chinese immigrant ghettos (a/k/a Chinatowns), burning homes and looting shops, shooting, lynching, scalping and branding the victims with hot irons. In one incident, a mob sliced off a Chinese miner’s genitals. In another, they tied a man to a wagon wheel driven at high speed until he was decapitated. In yet another, a Chinese was beaten to death and his corpse mutilated, which was commonly done. In 1885, in Rock Springs, Wyoming—a coal mining center along the Union Pacific Railroad—white vigilantes massacred 28 Chinese miners and left many others wounded.

In 1871, the largest mass lynching in U.S. history took place as a white mob of 500 tortured and murdered 17-20 Chinese in downtown Los Angeles. In the late 1800s, throughout California, anti-Chinese mobs spread like wild fire—Fresno, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Pasadena, San Jose, Stockton, Napa, Chico, Vallejo, Locke, Santa Cruz, Redding, Sonoma, Hollister, Vacaville, Truckee, Petaluma, San Francisco, Placerville, Nevada City, Carson, Yuba City, Santa Rosa, Lincoln and Wheatland. The ethnic cleansing of Chinese went on in other states—in Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Wyoming and beyond.

There was a larger global context for this crime in the U.S. Thousands of Chinese were being driven to America as a direct result of imperialist plunder and domination of China. Britain, France and the U.S. had carved up China into “spheres of influence” for foreign trade, opium traffic and missionaries. In the mid-1800s, China was defeated in two Opium Wars, first with England, then with England and France. As a result, China was forced to buy opium from the British and to pay war reparations to England and France, and open its borders to unrestricted exploitation by the Western powers. Foreign-owned manufacturing crushed local industry. And to pay reparations to the colonial powers, the Chinese government hit the people with huge tax increases. The horrible conditions of the Chinese people, who were overwhelmingly peasants at the time, became even worse and drove people to seek work in the U.S.

The Criminals

Leland Stanford was one of the foremost criminals. He built his empire as an industrialist, making millions as president of the Southern Pacific Railroad and later the Central Pacific Railroad. Leland Stanford was elected governor of California in 1861 and became a U.S. senator from 1885 to 1893. In a speech to the California legislature in 1862, he said: “The presence of numbers of that degraded and distinct people would exercise a deleterious [harmful] effect upon the superior [white] race.”

He was a partner in the railroad business with others such as Charles Crocker. Crocker used starvation tactics to break a strike by Chinese railroad workers. He also used his posse of well-armed white men to enforce this.

The use of official and unofficial violence worked together to enforce the super-exploitation and racist oppression of the Chinese immigrants.

This societal culture gave birth to populist union leaders like Dennis Kearny and his Workingman’s Party. Kearny said: “To be an American, death is preferable to life on a par with the Chinese.” He fanned the slogan “the Chinese must go!”

And the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1892: “White men and women who desire to earn a living have for some time been entering into quiet protest against vinyardists and packers employing Chinese in preference to whites.”

The Alibi

Through legal and extra-legal means, the ruling class mobilized U.S. society, including by using its press/media and mass culture, to broadly promote that the Chinese were responsible for taking the jobs of white workers, and driving down wages. Along with this, Chinese immigrants were depicted as inherently evil and sinister foreigners who caused all of America’s economic and social problems. It was said that they were importing mysterious exotic diseases, drugs and prostitution that had to be kept out of the U.S., and that those Chinese already here should submit to being exploited or else “choose to” live in fear.

The owners and operators of the capitalist press played a role in whipping up xenophobic, white supremacist hysteria. For example, in 1873, the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: “Who have built a filthy nest of iniquity and rottenness in our very midst? The Chinese. Who filled our workshops to the exclusion of white labor? The Chinese. Who drives away white labor by their stealthy but successful competition? The Chinese.” The paper’s owner, William Randolph Hearst, coined the phrase and promoted the racist fear of the “yellow peril.”

The Actual Motive

As a pool of super-exploitable labor, the Chinese were brought into the U.S.—some may even have been kidnapped—to build up the foundation of the U.S. economy at a time when it was expanding and needed this vast and cheap labor. But by the 1860s, mining was no longer profitable and the Chinese immigrants who came joined displaced gold miners working to build the railroads. By the 1880s, the U.S. capitalists did not have the same need for this cheap labor pool as they had in earlier decades. The California gold rush ended in 1855, the first transcontinental railway was completed by 1869, other industries had gotten off the ground, and the U.S. was mired in recession by the late 1870s. Southern plantation owners had stopped importing Chinese labor as the system of sharecropping and Jim Crow became more established.

Also, the decision to exclude Chinese immigrants forcibly asserted and helped maintain social cohesion based on white supremacy, particularly in the state of California. Targeting Chinese at a time of economic recession was a means of directing the anger and resentment of many lower-class whites (including in the labor movement) against the immigrants and away from the capitalist system itself as the cause of their misery. It also opened up certain jobs for white workers. And it served to prevent the growth of the non-white Chinese immigrant population (and in fact the Exclusion Act did radically diminish it).

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (renewed in 1892 and 1902) set precedent for legally discriminating against an entire group of people based solely on ethnicity and country of origin.

Sources

Revolutionary Worker (now revcom.us), February 16, 1997, “Sacramento Delta Blues: Chinese Workers and the building of the California Lees, 1860-1880”

Wikipedia—Chinese Exclusion Act, Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, History of Chinese-Americans

Chinese Exclusion Act (history.com)

LA Weekly, March 10, 2011, “How Los Angeles Covered up the Massacre of 17 Chinese,” by John Johnson Jr.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.