Case #59: The U.S. Invasion, Occupation, Domination, and Plunder of Cuba: 1898 to 1959

October 2, 2017 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian recently wrote that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

The Crime: In 1895, the Cuban people rose up against the Spanish colonialists who had ruled their country for more than 350 years. Cuba was one of the last outposts of Spain’s once vast empire and a source of immense profits from the sugar plantations. Spain waged a brutal counter-insurgency war, employing what later became known as the “strategic hamlet” strategy: forcing entire villages and small towns into concentration camps and carrying out a burn-all, kill-all policy in large regions along with efforts to starve rebellious regions into submission. Tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of people died at the hands of the Spanish military. But by the spring of 1898, the Spanish were all but defeated.

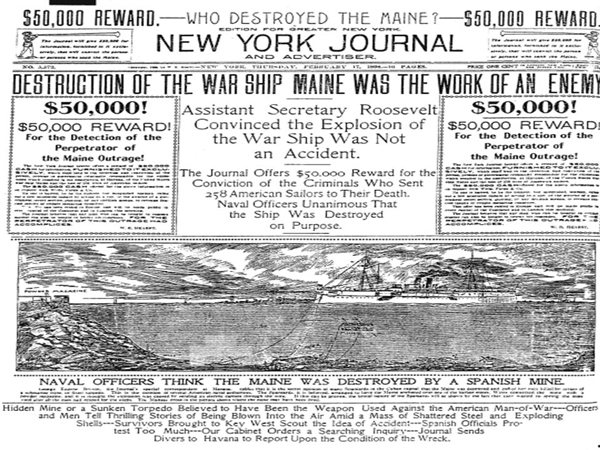

When the U.S. warship Maine blew up in Havana harbor, the U.S. press, especially that owned by William Randolf Hearst, initiated a fierce PR campaign to blame Spain and demanded U.S. military action against the Spanish. “Remember the Maine!” became a rallying cry for war.

As this was taking place, on February 15, 1898, a U.S. warship, the Maine, blew up in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, and 266 of the 350 sailors onboard were killed. U.S. president McKinley initially thought it was an accident, but the U.S. newspapers quickly blamed Spain for the explosion and demanded U.S. military action against the Spanish.1 “Remember the Maine!” became a rallying cry for war.

On April 20, the U.S. Congress passed the Teller Amendment declaring, “The United States ... hereby disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction or control over said island [Cuba] except for pacification thereof, and asserts its determination, when that is accomplished, to leave the government and control of the island to its people.” The amendment was meant to placate the Cuban people and people in the U.S. who had anti-imperialist sentiments opposed to foreign occupation.

Five days later, on April 25, the U.S. declared war on Spain. And on May 1, a U.S. invasion force commanded by future U.S. president Teddy Roosevelt landed at Santiago de Cuba and within a few weeks defeated a demoralized, outgunned Spanish force that had already been largely defeated by the Cubans. Shortly thereafter, Spain surrendered. While there were pro-U.S. elements among the rebels, including some who favored annexation to the U.S., the vast majority of rebels and their leadership wanted complete independence. The U.S. feigned sympathy with those aspirations and began what McKinley claimed was a temporary occupation.

The U.S. went on to directly rule Cuba for four years. Under their rule, black people were treated with utter contempt. For example, when the U.S. organized a Cuban Rural Guard, it created a segregated force with all-white officers. When the U.S. held an election in 1900, it pointedly excluded black people. A New York Times headline justified this exclusion in blatantly racist terms: “CUBA MAY BE ANOTHER HAITI.; Results Of Universal Suffrage Would Be a Black Republic—The Negroes Could Carry First Election.”

In May 1902, the last American troops sailed from the island, but not before the U.S. Congress passed the Platt Amendment,2 which gave the U.S. control over nearly every aspect of Cuban political life. Cubans were given an ultimatum: accept the Platt Amendment or face indefinite U.S. military rule.

With the Platt Amendment enshrining the right of the U.S. to intervene pretty much anytime it wished, American capitalist investors felt confident about moving into Cuba. Within a few years, 60 percent of Cuban rural property was in the hands of U.S. capitalists.

The resulting U.S. economic and political domination of Cuba was hugely advantageous to U.S. business interests. Under U.S. control, sugar plantations, even more dominant than they had been under the Spanish, ate up much of the arable land. The U.S. sucked wealth out of Cuba by dominating big agriculture and other businesses such as rum, tobacco, and cigar making, shipping, mining, and public utilities. Cuba became dependent on U.S. imports of food and nearly everything else, in a land that had been extremely fertile before its forests were burned down to make way for sugar.

The Cuban economy, built around the production of cane sugar, ground up hundreds of thousands of human beings in backbreaking and health-destroying labor. Rising and falling sugar prices and tariffs led to boom-and-bust cycles, which provided fabulous wealth for a few but ruin and immense suffering for many. Sugarcane workers worked unbearably hard during harvest months and went hungry much of the rest of the year. Often, it was family labor on tiny plots of land that enabled people to barely survive from harvest to harvest in the cane fields. Cubans worked on U.S.-owned cattle ranches, but only a tenth of the people in the countryside ever drank milk, and less than half of that percentage ever ate meat. Small farmers, often poor whites, were not much better off than plantation workers. Meanwhile hunger, poverty, and injustice were the lot for large sections of the Cuban population.

At various times in the decades following the U.S. withdrawal in 1902, U.S. troops returned to occupy Cuba. In 1906 to 1909 and in 1917 to 1922, the U.S. intervened militarily to put down protests against the corrupt and brutal government.

The U.S. intervention in 1912 came at a time of rebellion by Afro-Cubans against racial bigotry. The protests and an armed uprising (called the Armed Uprising of the Independents of Color, or the Negro Rebellion in the U.S.) against savage racism and oppression, were met with ruthless brutality. As many as 6,000 Afro-Cubans—rebels and the local population—were massacred, executed, or lynched by Cuban forces backed by nearly 3,000 U.S. Marines.

U.S. military power served to stabilize the imperialist hold on Cuba and to prop up some of the world’s most notorious tyrants, obsequious to Washington and unspeakably cruel toward the people.

In the 1930s Depression years, falling sugar prices led to widespread unemployment and starvation. In 1933 this exploded into a revolutionary movement that swept the island, including a paralyzing general strike initiated by transit workers and the seizure of dozens of sugar mills and the formation of “Soviets” by radicalized sugar workers.

Cuba’s president at that time, Gerardo Machado, was unable to defeat the forces rising against his regime. A special envoy, Sumner Welles, sent by U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt to deal with the crisis, pressured Machado to leave office, and a new U.S.-backed president assumed power. Still, the crisis and mass rebellion continued and spread into the ranks of the military. A group of non-commissioned officers led by army sergeant Fulgencio Batista seized control of the Cuban army and together with students and others drove Machado’s replacement from power. A reform government briefly held power, withdrew from the Platt Amendment, and began to make some changes that threatened U.S. economic and political interests. The U.S. withdrew support from that government and maneuvered against it. With U.S. help, Batista became the new head of the Cuban military and assumed the role of a U.S. strongman, ruling Cuba directly or from behind the scenes until the revolution in 1959.

Like other U.S.-backed rulers before him, Batista relied on repression, racism, torture, and public executions to stay in power. Under his rule, U.S. domination of Cuba’s economy reached new heights. By the late 1950s, U.S. financial interests owned 90 percent of Cuban mines, 80 percent of its public utilities, 50 percent its railways, 40 percent of its sugar production, and 25 percent of its bank deposits.

Cuban society was as devastated and dominated as its economy. Under the watchful eyes of Washington’s ambassadors, the U.S.-based Mafia set moral standards and the Catholic Church blessed them. Among their most sacred values were men’s right to rule over women and women’s confinement to the categories of mothers, wives, mistresses, and prostitutes. Prostitution flourished—in brothels and on the streets—10 percent of Havana’s population “served” American military men, civilian sailors, and sex tourists. The biggest growth industry was casinos.

Ordinary Cubans had no rights. The aspirations of even the better-off middle classes and professionals were trampled underfoot by the country’s corrupt, vicious, and tiny ruling class in association with the U.S. monopoly capitalists and their political representatives in Washington.

In 1952, Batista, who had been out of the presidential office for a number of years, returned by way of a coup. The years that followed saw corruption on an even more vast scale, along with increasing anti-government rebellion. An effort to provoke an insurrection in 1953 by a group led by Fidel Castro was followed by intense and bloody repression. Perhaps as many as 20,000 students, workers, and others were murdered. Many others were jailed and tortured. The U.S. supported and backed the Batista regime in this bloody repression. Yet discontent spread and a guerrilla movement led by Castro’s 26th of July Movement gained strength in Cuba’s mountain areas.

On January 1, 1959, Batista fled Cuba along with members of his family and government, taking with him hundreds of millions of dollars stolen from the Cuban people. A week later, Castro and his army rolled victoriously into Havana. After 61 years, the era of U.S. economic and political domination of Cuba, with all its plunder and terror, came to an end. But while Cuba did break from direct U.S. domination, it did not break from the overall grip of imperialism.3

The Criminals

The entire U.S. ruling class for many decades agreed on the need to control and dominate Cuba. President McKinley oversaw seizing of the island in 1898 under the pretext of guaranteeing Cuban sovereignty. The U.S. media whipped up war fever by blaming Spain for the sinking of the battleship Maine, even though they had no real evidence. Theodore Roosevelt, later the U.S. president, commanded a regiment in the invasion force. General Leonard Wood served as the U.S. military governor of Cuba until 1902. Sumner Welles, President Franklin Roosevelt’s special envoy, tried to save the brutal Machado regime and then negotiated Machado’s departure and replacement in 1933. Under President Truman, Batista carried out the coup that brought him to power in 1952. Under President Eisenhower, Cuba became the playground of the U.S. Mafia. Under every president and every U.S. regime from 1898 to 1959, Cuba was an exploited neo-colony of the U.S.

The Alibi

As the defeat of the Spanish colonialists seemed imminent in 1898, the U.S. claimed that the Cuban people were incapable of independent rule because there were too many divisions and conflicts among the anti-colonial forces. There were also outright racist justifications, like a U.S. general who said of the Cuban people, “They are no more capable of self-government than the savages of Africa.”

When the U.S. warship Maine blew up in Havana harbor, the U.S. press, especially that owned by William Randolph Hearst, initiated a fierce PR campaign to blame Spain (the cause of the blast remains inconclusive up to today) and whipped up jingoistic sentiment for military action. The press campaign was an important factor in building support for the U.S. invasion of Cuba in May 1898.

In Washington, politicians played on those sentiments. They claimed the U.S. had no colonial or imperialist ambitions in Cuba, while pontificating about its moral responsibility to come to the aid of the oppressed Cuban victims of Spanish colonialism. At the same time, they promoted and played on racial hatreds and fears that the revolution in Cuba could lead to a dangerous “Negro republic.”

The Actual Motive

The U.S. rulers had their eyes on Cuba at least since the 1820s when Southern slave owners feared that a rebellion of Spain’s slaves, along the lines of the revolution against slavery in Haiti, would be detrimental to the stability of the U.S. slave system. In the 1840s, the U.S. seizure of Mexican territories sparked enthusiasm for further expansion, and some looked then to Cuba.

By the late 1800s, as capitalism further developed in the U.S., monopolies emerged in various industries, as did big banks. They needed new areas to invest large amounts of accumulated wealth (capital). Industries needed access to resources and markets. There was intensifying rivalry among the emerging imperialist powers of the world for control of regions of the globe. The U.S. claimed the Caribbean territories and Latin America as its turf. The weakening of the Spanish empire and the rebellions in Spanish colonies opened opportunities for U.S. imperial expansion.

The seizure of Cuba (and other Spanish colonies—Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines) in the Spanish-American War was not only in order to gorge on the exploited wealth but to prevent rivals from moving in. The U.S. was very explicit about this. The Platt Amendment specifically prohibited any power, other than the U.S., from establishing bases on Cuba. The U.S. also feared that the revolutionaries in Cuba—hundreds of thousands of poor working people, small farmers, the majority of them Black people who had been slaves until the 1880s, and some middle class professionals, and members of the Cuban elite—would defeat Spain and set up an independent country that would be unfavorable to U.S. interests.

The invasion of Cuba and other Spanish territories at the end of the 19th century signaled the emergence of the United States as an imperialist world power. Its successful invasion, domination, and plunder of Cuba was but a glimpse of the immense crimes to come.

Sources

“A World to Win News Service: What Future for Cuba Did the Handshake Between Barack Obama and Raúl Castro Herald?” Revolution/revcom.us, March 28, 2016

Cuba, A New History, Richard Gott, Yale University Press, 2014

Cuba, Between Reform and Revolution, Louis A. Perez, Oxford University Press, 1995

The Cuban Reader History, Culture, Politics, Aviva Chomsky, Duke University Press, 2003

The War of 1898, Louis A. Perez, University of North Carolina Press, 1998

Wikipedia on Fulgencio Batista, Gerardo Machado, Negro Rebellion

AfroCubaWeb on the 1912 Massacre

Footnotes

1. Following the explosion, the U.S. claimed that Spain used a mine to blow up the Maine. Years later, evidence mounted that the explosion may have been from within the ship, from its boiler room, not from outside. [back]

2. The Platt Amendment contained eight provisions. The key ones were the third, which gave the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuba militarily, and the seventh, which gave the U.S. the right to maintain a base on the island. Because of the seventh provision the U.S. was able to set up a military base at Guantánamo, which it maintains to this day. [back]

3. See “Re-colonization in the Name of Normalization: Behind the Re-Establishment of U.S.-Cuba Diplomatic Relations,” by Raymond Lotta at revcom.us. [back]

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.