Case #18: The LAPD—150 Years of Murder, Brutality, Racism and Repression

| revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIMES

The LAPD, with its slogan of “To Protect and Serve,” is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year. But what is its actual history—from beginning to today? And what does it say about the actual history of this country and the role of the police?

1950-1966: Chief Parker and the Watts Rebellion—A More “Professional” and More Brutal LAPD

William Parker, who became police chief in 1950, was hailed as a modernizer. But there was nothing “modern” about his stone-cold racism. When he was sworn in, he declared, during a period when tens of thousands of Black people were migrating to LA, that “Los Angeles is the white spot of the great cities of America today. It is to the advantage of the community that we keep it that way.”

A decade later, Parker told the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights that Blacks and Latinos were more likely to commit crimes than white people, and that the barrios had a high crime rate because people there were a step removed from “the wild tribes of Mexico.”

In between, Parker, who called the police the “Thin Blue Line” protecting civilization (i.e., white supremacy), unleashed a reign of terror against Black and Brown people. “The policing of the ghetto was becoming simultaneously less corrupt but more militarized and brutal,” writes Mike Davis. Previously, LAPD officers often “shook down” the interracial, Black-owned nightclub scene on Central Avenue for bribes. Now Parker’s police shut it down—even blockading Black-owned stores and warning white customers away.

This police terror escalated in the 1960s. In April 1962, some 75 LAPD cops shot up a Nation of Islam mosque, killing one and wounding six others. Why? Some cops had gotten in a beef with two members of the mosque after they accused them of having a “suspicious amount of clothes in their car.” It turned out the two owned a dry cleaning business. After the assault Malcolm X came to LA and condemned Parker for “filling his men with hatred for the Black Community.”

1965: The Watts Rebellion

Between 1963 and 1965, thousands of young Black men were harassed or brutalized, and 60 Black people were shot by the LAPD—27 in the back. Then an incident of this kind of everyday harassment turned into something else.

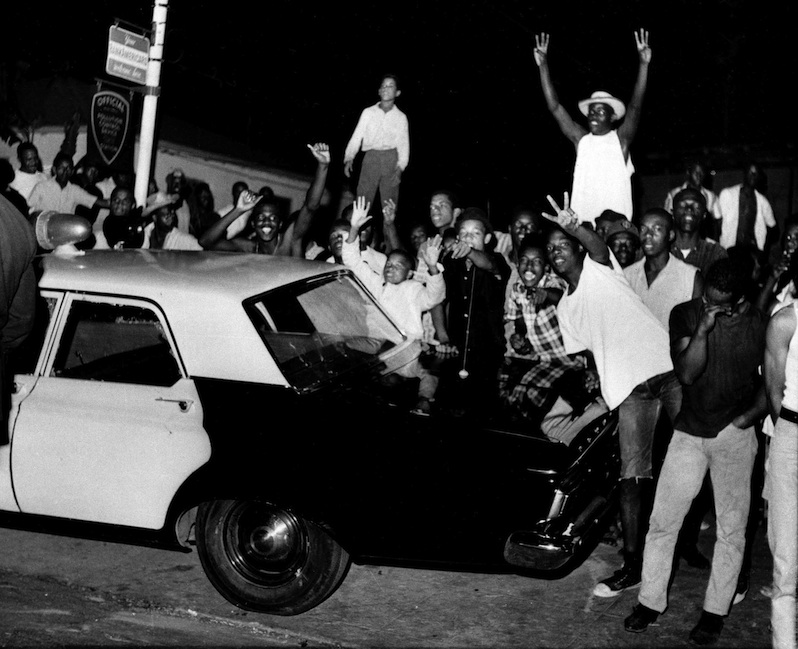

1965 Watts Rebellion: Black people stood up in anger and defiance at the LAPD—an estimated 75,000 people took part—rocking LA and sending shockwaves around the world. (Photo: AP)

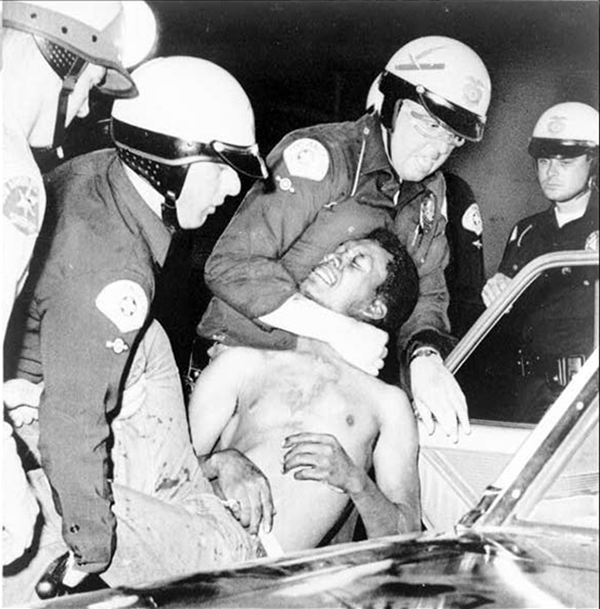

More than 5,000 youth were injured or arrested. Photo: AP

More than 30 Black and Latino people were unjustly shot to death by pigs. Photo: Creative Commons

According to various accounts, on the evening of August 11, a California Highway Patrol (CHP) cop stopped Marquette and Ronald Frye on suspicion of drunk driving. Ronald, who was a passenger, went to get their mother, as a crowd began to gather. When Ronald and his mother came and the crowd had grown to several hundred, Marquette exploded in rage, “cursing and shouting at the officers [saying] they would have to kill him to take him to jail.” An altercation ensued and all three Fryes were arrested and taken to jail.

But the growing crowd wasn’t having it. They cursed the CHP. The pigs decided to assert their authority and waded into the crowd to arrest one agitator and a woman who supposedly spit on them. A rock hit the CHP cruiser as it was leaving, and when word circulated that a bad bust had gone down and a pregnant woman had been abused, the community rose up.

Black people stood up in anger and defiance—an estimated 75,000 people took part—rocking LA and sending shockwaves around the world. A feeling of freedom and liberation surged through the Black community as the hated pigs had been driven out—and it took them nearly a week to regain control. The LAPD was forced to put 46.5 square miles of the city under military-enforced curfew, mobilize 21,000 cops and National Guard troops, and lock down and retake one neighborhood after another. More than 30 Black and Latino people were unjustly shot to death by pigs who were totally rampaging, and 5,000 were injured or arrested—but it still took the authorities six days to bring the Watts Rebellion to an end.

The 1960s-1980s: Spying, Suppressing, and Murdering Radicals and Revolutionaries

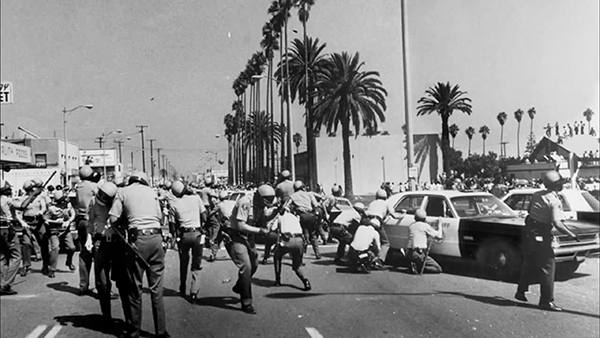

LAPD attack a 1967 protest against the Vietnam War at Century City Mall. Hundreds of police attacked them. Photo: courtesy LA Times Photographic Archive, Young Research Library UCLA

The Watts uprising was a turning point in the 1960s, helping to usher in a period of massive upheaval and rebellion in cities across the country. The LAPD under Parker protégés Edward M. Davis (1969-1978) and Daryl Gates (1978-1992) responded with paramilitary assault units, including SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams, and stepped up spying aimed especially at radical and revolutionary forces.

The LAPD’s Murderous Assaults on the Black Panther Party

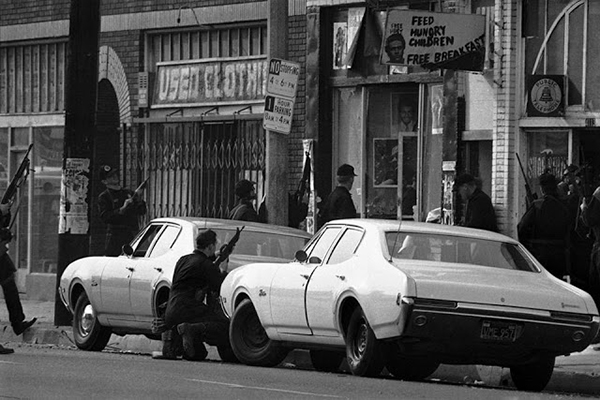

On December 8, 1969, four days after the Chicago Police Department and the FBI assassinated Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton, the LAPD launched a predawn assault on the LA Panther headquarters at 41st and Central. Inside their sandbag-fortified office, 11 Panther members, including Vietnam vet Geronimo Pratt, engaged in a five-hour shootout with 350 cops, SWAT teams, and LAPD helicopters, that rained bullets and tear gas into the Panther house in Watts. Five thousand rounds of ammunition were exchanged. Masses of people from the area turned out in support, along with student radicals, and this helped to prevent the police from unleashing an even worse barrage.

December 8, 1969, SWAT teams and LAPD helicopters rained bullets and tear gas into the Black Panther Party house in Watts.

Roland Freeman got buckshot in his legs from a police shotgun, and a single shot shattered the bone in his arm. A police sniper’s bullet tore through the legs of Tommy Lewis, one of the two women there. Not being able to stop the bleeding of some of their comrades, the Panthers called an end to the exchange. When it ended, four Panthers and four SWAT cops were wounded but there were no fatalities.

In the 2006 documentary by Gregory Everett, 41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers, Wayne Pharr recalls what he felt during that intense standoff facing overwhelming murderous police firepower: “That was the only time as a Black man in America that I ever felt free, was the five hours that I was in the shootout…. For those five hours, I was in control of my destiny…” Millions of people also saw the LA-BPP self-defense action as heroic and took inspiration from it.1

The 1970 Chicano Moratorium and the Murder of Rubén Salazar

On August 29, 1970 over 25,000 Chicanos marched in East LA in the Chicano Moratorium, demanding an end to the Vietnam war and to the oppression they faced as a people. (Photo: Los Angeles Public Library)

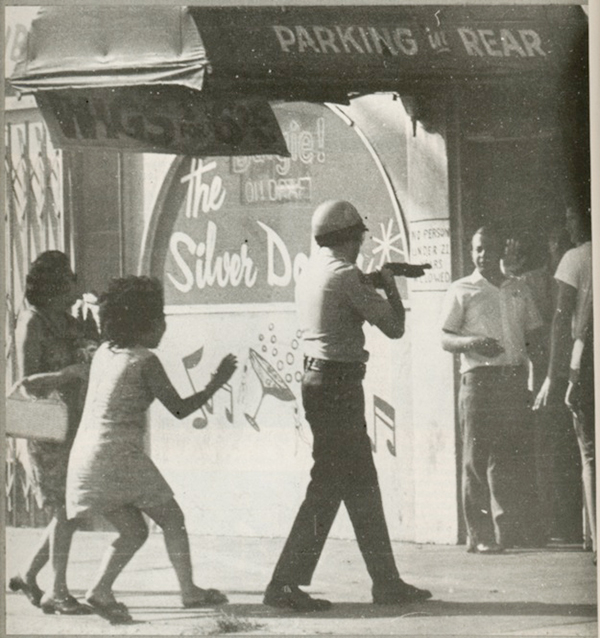

An LA County Sheriff’s deputy shot a tear gas canister through the door of the Silver Dollar Bar, hitting prominent Chicano journalist Rubén Salazar in the head and killing him. (Photo: Raul Ruiz)

The LA County Sheriffs and the LAPD came out in force against the Chicano Moratorium. They reacted to a shoplifting situation by declaring it an illegal assembly and sheriff’s deputies and LAPD stormed into the crowd, shooting tear gas and swinging their batons. (Photo: CreativeCommons)

The LAPD and other law enforcement agencies had the burgeoning Chicano liberation movement in their crosshairs since March 1968, when some ten thousand Chicano students in East LA walked out of their predominantly Mexican-American high schools in protest of the inferior education available to them.

So on August 29, when over 25,000 Chicanos marched in East LA in the Chicano Moratorium, demanding an end to the Vietnam war and to the oppression they faced as a people, the LA County Sheriff’s Department and the LAPD came out in force. Toward the end of this largely peaceful march, some youth allegedly shoplifted drinks from a nearby store and ran into the crowd. The sheriff’s deputies seized on this to declare an illegal assembly and deputies and LAPD stormed into the crowd, shooting tear gas and swinging their batons. People did not disperse, but courageously stood their ground and fought back. At one point, a sheriff’s deputy shot a tear gas canister through a shop door that hit prominent Chicano journalist Rubén Salazar in the head killing him. Two others were also killed before the day was over. Salazar had given voice to Chicano demands, and many demanded an investigation feeling the Sheriff’s Department may have targeted Salazar for assassination, an investigation that an inquest jury found was warranted. Yet DA Evelle J. Younger refused to proceed.

Militant Chicanos held three other major protests over the next five months which were attacked by the LA sheriff’s deputies and LAPD, including on January 31, 1971 when one demonstrator was killed and thirty-five were wounded.

May 17, 1974: The SLA Massacre

The LAPD fired some 1,200 rounds of ammunition into the tiny home as six SLA members shot back. Teargas containers thrown into the house ignited a fire, but the SLA refused to surrender and all six were killed by burns and smoke inhalation. (Photo: AP)

On May 17, some 500 LAPD cops surrounded and laid siege to a small house in Compton where they suspected members of the small radical group the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) were hiding out. Then they opened fire. The SLA had carried out a series of actions—including the highly publicized kidnapping of ruling class heiress Patty Hearst, demanding her family distribute food to poor people in California, which the family did.2 (Other SLA members, not present, were later arrested and sent to prison for murder, bank robbery, and kidnapping.)

The LAPD fired some 1,200 rounds of ammunition into the tiny home as six SLA members shot back. Teargas containers thrown into the house ignited a fire, but the SLA refused to surrender and all six were killed by burns and smoke inhalation.

April 22, 1980: The Murder of Revolutionary Communist Damián García

Damián García raising the red flag on top of the Alamo.

On April 22, 1980, Damián García, a member of the Revolutionary Communist Party, was building for May First in the Pico-Aliso Housing Project in East Los Angeles. A month earlier Damián and two other members of the “May Day Brigade” had scaled the infamous Alamo, lowered the flag of Texas and raised the red flag of revolution. This powerful internationalist statement made the front page of newspapers in many countries of Central and South America—and made Damián a “dangerous individual” in the eyes of this system and its political police, and the LAPD.

As Damián and his comrades moved through the housing project, he was confronted by a man who said, “You hate the government. I am the government. Your flag is red. Mine is red, white and blue.” He and others jumped the Brigade in what at first appeared to be a fistfight. But suddenly Damián fell to the ground and died—slashed in the neck, abdomen and back.

The LAPD quickly claimed it had been a gang killing, and that the gang member responsible for Damián’s murder had himself been killed six weeks later—case closed. But two years later, an ongoing investigation revealed that a police agent (Fabián Lizárraga), who went by the alias "Ernie Sánchez," had been assigned by the LAPD’s Public Disorder Investigation Division (PDID) to target Damián.

The PDID had been formed in 1970 and it had infiltrated, spied on, and disrupted over 200 groupings and kept files on 50,000 people—including the LA Times, the National Organization for Women, Students for a Democratic Society at UCLA, the Peace and Freedom Party, and the Black Panther Party (BPP). They also spied on members of the City Council, the Police Commission, and at least one judge.

One week after Damián and his comrades scaled the Alamo, “Sánchez” had infiltrated the May Day Brigade. He was with Damián daily and fed the PDID information about Damián’s schedule, including the day he was murdered. And Sánchez was standing five feet away when Damián was assassinated.

In 1983, an ACLU lawsuit accused the PDID of illegally spying on 131 social movement activists and organizations. This revelation of the extent of LAPD spying and its targeting of political activists—including Damián—caused a major social uproar and forced the Police Commission to disband the PDID. (It was replaced by an anti-terrorism division). Adding to the outrage, it also came out that one PDID cop, Jay Paul, had defied a 1976 order by the Police Commission to destroy the unit’s confidential intelligence files on revolutionaries, radicals, members of the City Council, the Police Commission, and at least one judge and instead stored them in his garage and shared the files with a private, fascist intelligence dissemination operation called Western Goals.

The Gates Years, 1978-1992:

The LAPD sets the standard for state-sponsored racist terror and suppression

The Murder of Eula Love. Daryl Gates took over the LAPD in 1978 and quickly became infamous for his sneering, open racism, and his war-like approach to policing Black and Brown people. Gates ushered in his tenure with, among other horrors, the murder of 39-year-old mother of three Eula Love on January 3, 1979. Love was recently widowed and struggling to raise three kids on a limited income in her small home in South Central. That day she was upset because a utility man had come and tried to turn off her power. They got into an altercation and he called the police. When the police arrived Eula came out of her home while her children stayed inside. The cops talked to her for two to three minutes before opening fire, hitting her with twelve .38-caliber slugs from eight to twelve feet away. They claimed she’d advanced on them with a knife in her hand, but it turned out she was moving away.

After they murdered Eula, the cops rolled her lifeless body over and handcuffed her on the grass in her own front yard. There was a major outpouring of protest after her murder, but Gates responded by mocking and assaulting her—and all Black people again—declaring the white pig who shot her was “just as much a victim of this tragedy as (she was).”

With LA’s Black mayor, Tom Bradley, and other Black “leaders” remaining silent as the so-called “war on drugs,” launched in earnest by Ronald Reagan in 1982, escalated, Gates was emboldened to openly insult and taunt Black and Brown people as part of the terror the LAPD was raining down on them. In 1982, after a string of young Black men were killed by LAPD ”chokeholds,“ Gates claimed their deaths were caused by being Black: “We may be finding that in some Blacks when [the carotid chokehold] is applied the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as they do on normal [sic] people.”

The “War on Drugs” and Operation Hammer 1988-1990. The “war on drugs” was not about bringing down crime; it was a war on oppressed people aimed at ramping up suppression and social control—a counterinsurgency before the insurgency. And the LAPD under Gates was in the vanguard of waging, expanding, militarizing, and brutally carrying it out.

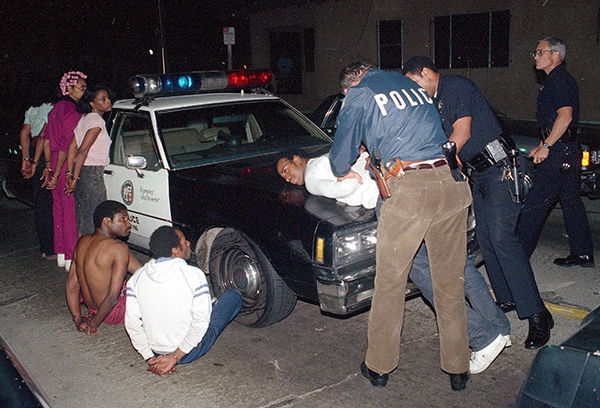

The “war on drugs” was not about bringing down crime; it was a war on oppressed people. A thousand extra-duty patrolmen, backed by elite tactical squads and a special anti-gang taskforce formed Operation HAMMER. They arrested more Black youth than at any time since the Watts Rebellion of 1965. (Photo: AP)

By 1987, with crack spreading and violence surging among the youth of different gangs and sets —and hysteria about the situation fanned by the media, Democrats, and Republicans—the LAPD launched the so-called Gang Related Active Trafficker Suppression program (GRATS) which targeted “drug neighborhoods” with 200-300 police ordered to stop anyone “suspected” of being a gang member based on “criteria” like clothing and hand gestures. Gates announced that full manpower reserves of LAPD would be thrown into super-sweeps called Operation HAMMER.

Author Mike Davis describes Operation HAMMER’s first action on April 9, 1988:

A thousand extra-duty patrolmen, backed by elite tactical squads and a special anti-gang taskforce, bring down the first act of “Operation HAMMER” upon ten square miles of Southcentral Los Angeles between Exposition Park and North Long Beach, arresting more Black youth than at any time since the Watts Rebellion of 1965… Kids are humiliatingly forced to “kiss the sidewalk” or spread eagle against police cruisers while officers check their names against computerized files of gang members. There are 1,453 arrests; the kids are processed in mobile booking centers, mostly for trivial offences like delinquent parking tickets or curfew violations. Hundreds more, uncharged, have their names and addresses entered into the electronic gang roster for future surveillance.

Daryl Gates called it “war.” The Chief of LAPD Hardcore Drug Unit said, “This is Vietnam here.”

The Dalton Street Raid. One of the infamous operations during Operation HAMMER was the Dalton Street raid on August 1, 1988. Eighty-eight cops from the infamous Southwest Division swooped down on a group of apartments on Dalton Avenue near Exposition Park. They wielded shotguns and sledgehammers and shouted racist slurs and insults. The LA Times reported:

An infamous operation during Operation HAMMER was the Dalton Street raid on August 1, 1988. Eighty-eight cops from Southwest Division swooped down on a group of apartments on Dalton Avenue. They wielded shotguns and sledgehammers and shouted racist slurs and insults. (Video screen capture)

Residents… said they were punched and kicked by officers during what those arrested called “an orgy of violence….”

They also accused the officers of throwing washing machines into bathtubs, pouring bleach over clothes, smashing walls and furniture with sledgehammers and axes, and ripping an outside stairwell away from one building.

[They] destroyed family photos, ripped down cabinet doors, slashed sofas, shattered mirrors, hammered toilets to porcelain shards, doused clothing with bleach and emptied refrigerators. Some officers left their own graffiti: “LAPD Rules.” “Rollin’ 30s Die.”

Damage to the apartments was so extensive that the Red Cross offered disaster assistance and temporary shelter to displaced residents—a service normally provided in the wake of major fires, floods, earthquakes or other natural disasters.

As Mike Davis reported in City of Quartz, at Southwest Division, 32 people arrested were forced to whistle the theme from the Andy Griffith TV show as they had to go through a gauntlet of pigs beating them with fists and flashlights. After all the lives and homes devastated, the result was two minor drug arrests.

Gates institutionalized the Operation HAMMER sweeps as semi-permanent occupations of neighborhoods of the oppressed, including the largely immigrant neighborhood of Pico Union, later the site of the infamous Rampart scandal, which Gates claimed was “a veritable flea market for drug dealers.”

By 1990, the LAPD and the LA County Sheriff’s Department together had detained or arrested some 50,000 suspects—roughly half the entire population of 100,000 Black youth in Los Angeles at the time! In many of these highly publicized sweeps, more than 90 percent were released without charges —but their innocence didn’t necessarily keep them out of the LAPD’s growing gang database.

All of this was facilitated by support from the media, which fanned horror stories about the masses. Leading Democrats, including Black politicians like Senator Diane Watson, whose press secretary said, “when you have a state of war, civil rights are suspended for the duration of the conflict,” also joined in. Reformist Black “leaders” like the Urban League and SCLC started arguing that the problem was “too little policing” —not police brutality. “Progressives” like Ishmael Reed and Harry Edwards joined in denouncing Black youth as beyond hope, and demanded they be locked up to protect the rest of the Black community (i.e., better-off working, middle, and upper class Black people).

Meanwhile, California state laws were being passed—with Democratic backing as well as Republicans—targeting Black and Latino youth in the name of a “war on gangs” and “war on drugs.” One was the 1988 “Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act” (STEP), which made alleged membership in a “criminal gang” a felony. Such laws, along with the much harsher punishment for crack as opposed to powder cocaine, led to ensuring people of color and the poor were locked up much more frequently and for longer than white people—and all this was a big part of the explosion of mass incarceration, disproportionately targeting Black and Latino youth. To this day, with an average population of 17,000 to 20,000, the LA County Jail is the largest jail system in America.

1991-92: The Rodney King Beating and the LA Rebellion3

The night of March 3, 1991, Rodney King, a young Black man, was pulled over for speeding. LAPD and Highway Patrol officers flooded to the scene and over the next few minutes, at least seven mercilessly beat and tased King, crushing the bones in his face, breaking his teeth and ankle, and causing numerous lacerations and internal injuries. Over a dozen other cops stood around laughing and encouraging the beating.

Within minutes after the four cops who beat Rodney King were acquitted, people began gathering all over LA, hundreds at LAPD headquarters. Protests erupted in many neighborhoods. Here Parker Center is in flames. (Photo: AP)

Authorities mobilized the largest domestic military operation since the 1960s: nearly 20,000 police, National Guard troops, federal military troops, FBI, Border Patrol, and others. (Photo: AP)

By the time it ended, the 1992 LA Rebellion was the largest urban rebellion in U.S. history. Some 63 people had been killed, 10 by law enforcement—nearly 80 percent Black and Latino. Some 12,000 people were arrested. (Photo: AP)

A resident across the street videotaped the whole assault, and the tape was repeatedly shown on TV. Despite police claims that the video didn’t tell the real story, public anger was so intense that prosecutors were forced to charge four of the white officers with excessive force to try to contain things.

A year later the four officers went on trial. The trial had been moved to the virtually all-white Simi Valley. There was a widespread feeling that this time the brutality and the treatment Black people continually faced was caught on tape for all to see, and that the officers had to be found guilty. But on April 29, 1992, the Simi Valley jury verdict acquitting them of all charges was broadcast on live TV.

Within minutes, people began gathering all over LA, hundreds at LAPD headquarters. Protests erupted in many neighborhoods, but the gathering at Florence and Normandie became a flashpoint that propelled the whole uprising. By that evening, fires were burning throughout LA and protests were jumping off across the country. Over the next three days, the authorities mobilized the largest domestic military operation since the 1960s, with nearly 20,000 police, National Guard troops, federal military troops, FBI, Border Patrol, and others on the streets. By the time it ended, the 1992 LA Rebellion had become the largest urban rebellion in U.S. history. Some 63 people had been killed, 10 by law enforcement—nearly 80 percent Black and Latino. Some 12,000 people were arrested.

From 1992 to Today: Cosmetic Changes, Same Racist, Murdering LAPD

Over the 27 years since the LA Rebellion, various commissions, different police chiefs, and many calls for and declarations of change, the LAPD has continued to be the same savage machine of murder, brutality and repression. A few examples:

- Stolen Lives: Killed by Law Enforcement, published in 1999, was able to document 197 police killings in the LA area in the 1990s (some by LA sheriff's deputies and other smaller police departments, but most by the LAPD.)

- 1999 Rampart scandal. In 1999, it came to light that the Rampart Division of the LAPD and its elite “anti-gang” CRASH unit (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums) had been terrorizing the residents of Pico Union, a largely Spanish-speaking area. This included murder, attempted murder, brutality, robbery, extortion, drug dealing, and routinely framing and convicting thousands of people based on lies, planted “evidence,” and trumped-up charges—including Javier Francisco Ovando, a 19-year-old Honduran immigrant who was wantonly shot four times, paralyzed for life, then convicted of attempted murder! Over 70 CRASH cops were involved, but only four were put on trial. The trial exposed some of their gruesome crimes and the jury found them guilty. Instead of carrying out the verdict, LA Superior Court Judge Josephine Connor threw out the verdict and exonerated the pigs!

- 2002: When former NYPD head William Bratton became chief he brought “Stop and Frisk” from NYC to LA with a vengeance. The number of stops went from 587,000 in 2002 to 875,000 in 2008.

- 2009-2018: Charlie Beck and more police murder. Beck was featured as a “reformist” chief by Obama at a White House meeting. In reality, on his watch from 2015 to 2017, the LAPD had the highest number of people killed by police in any city in the whole country. The LAPD killed 19 in 2015, 20 in 2016, and 17 in 2017.

- Political persecution of revolutionary and anti-fascist activists: 11 members of Refuse Fascism and the Revolution Club were criminally charged for engaging in or supporting nonviolent civil disobedience and political protests from September 2017 through March 2018. This included holding banners across the 101 freeway saying “Trump/Pence Must Go!” and disrupting Trump’s Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin at UCLA. Some of the dangerous elements of the prosecution include two Refuse Fascism activists being singled out for “criminal conspiracy”; involvement of LAPD’s “Major Crimes/Anti-Terrorism Division,” which has a history of targeting progressive and radical movements; use of a “confidential informant” to spy on and illegally record members of Refuse Fascism and the Revolution Club.

THE CRIMINALS: The entire LAPD, from 1869 until today, all the cops listed above, and all the politicians—Democrats and Republicans—and media who backed them.

THE ALIBI: See “In Their Own Words” sidebar

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE:

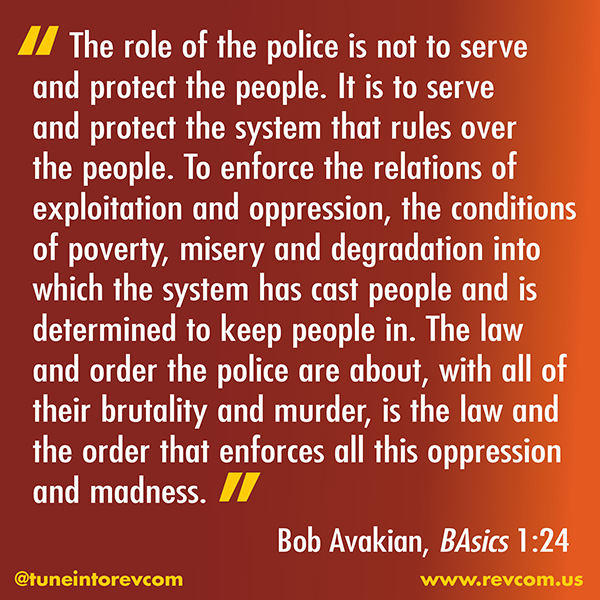

All in all, the LAPD is a textbook illustration of Bob Avakian’s point in BAsics:

The role of the police is not to serve and protect the people. It is to serve and protect the system that rules over the people. To enforce the relations of exploitation and oppression, the conditions of poverty, misery and degradation into which the system has cast people and is determined to keep people in. The law and order the police are about, with all of their brutality and murder, is the law and the order that enforces all this oppression and madness.

SOME KEY SOURCES:

Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (Verso 1990), in particular chapter five, “The Hammer and the Rock”

“A History of the LAPD, 1900-1965: Historic Racial and Class Repression throughout the 20th Century Leading to the Creation of SWAT by the LAPD following the Watts Unrest of 1965,” Clinton Clad-Johnson, Senior Thesis for Dr. Juan Gómez-Quiñones

“The Raid That Still Haunts L.A.,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 2001

Edward J. Escobar, “The Unintended Consequences of the Carceral State: Chicana/o Political Mobilization in Post–World War II America,” Journal of American History, June 2015

American Crime Case #66: The “War on Drugs,” 1970 to Today, revcom.us, March 6, 2017

John Johnson, Jr., “How Los Angeles Covered up the Massacre of 17 Chinese,” LA Weekly, March 10, 2011

American Crime Case #67: 1848-1900: Brutal Exploitation and Ruthless Oppression of Chinese Immigrants, revcom.us, February 13, 2017

1. During the subsequent trial of the Panthers arrested, it was revealed that two undercover LAPD informants (Melvin “Cotton” Smith and Louis Tackwood) had been in the BPP headquarters and had given the LAPD the layout of the office and fabricated “intelligence” that military weapons were being stored there, which was used to justify the assault.

The LA chapter of the Black Panther Party was subjected to more police assaults than any other chapter nationwide. They included:

- The January 1, 1969, murder of Captain Franco (Frank Diggs) in Long Beach.

- On January 9, 1969, John Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, BPP leaders in Los Angeles, were gunned down by members of the US Organization (United Slaves), a reactionary nationalist group led by Ron Karenga, during a meeting at UCLA to discuss forming a Black Studies Department. Their assassinations were a result of COINTELPRO actions against the BPP. It is not known if the LAPD played a role. See American Crime Case #42: COINTELPRO—The FBI Targets the Black Freedom Struggle, 1956-1971, revcom.us, April 30, 2018.

- In May 1969, the LAPD carried out 56 arrests of 42 Panthers.

- On September 8, 1969, an armed LAPD unit raided the Panthers' free-breakfast-for-children program in Watts.

- Panther Bruce Richards was wounded and Panther Walter Toure Poke was killed in a shoot-out with the LAPD on October 10, 1969.

- Geronimo Pratt was arrested in 1970 and then convicted for the murder of a Santa Monica schoolteacher on trumped up charges, based on a testimony of an LAPD informant, and held in prison for over two decades.

- In November 1970, the LAPD raided the LA BPP’s childcare center, holding guns on the children and beating up the Panther in charge. [back]

2. Then-California governor Ronald Reagan said he hoped there would be an outbreak of botulism among the poor who received the food. [back]

3. The LA4. In the aftermath of the rebellion, one of the main ways the authorities tried to go after it was the prosecution of the LA4—four young Black men charged with the attack on white truck driver Reginald Denny at Florence and Normandie. While the judge, prosecutor and mainstream media tried to railroad them to prison, the jury would not go along and delivered not guilty verdicts on nearly all of the charges. In a heroic development, when Denny himself took the stand he called for no jail time and expressed some real understanding of what led to the rebellion. The Los Angeles Times quoted Denny: “Everyone needs respect.... And as soon as you take a group of people, and put them on a shelf and say they don’t count. Let me tell you, they count in a big way.... It’s hard saying what those guys have gone through.” The RCP joined with a wide range of people to mount a campaign to defend the LA4. “Free the LA4+! Defend the Los Angeles Rebellion!” and “No More Racist Pig Brutality!” were two of the slogans. “20th Anniversary of the Los Angeles Rebellion—It’s Right to Rebel Against Injustice!“ revcom.us, April 22, 2012 [back]

“How Long?! How Many More Times Do The Tears Have To Flow?”

A clip from BA Speaks: REVOLUTION—NOTHING LESS!, a film of a talk by Bob Avakian given in 2012. Watch the whole talk at revolutiontalk.net.

1869-1950: The founding and early “lynch-mob” years

The LAPD was founded in 1869, modeled after the paramilitary L.A. Rangers and City Guards and their lynch-mob spirit, and it’s been a brutal, murderous, racist operation ever since. Los Angeles was being built on land recently seized from Mexico and stolen from Native Americans, and it had a significant and growing nonwhite population. The LAPD’s job from day one was focused on confining and suppressing the basic masses, especially Black, Brown, Native American and other non-white people, and relentlessly assaulting those who organized and politically fought back.

Just some of its crimes during those early years:

In 1871, the largest mass lynching in U.S. history took place—against Chinese immigrants. Los Angeles authorities, including the LAPD, did nothing to stop the carnage. Bodies of some of the murdered Chinese immigrants.

In 1871, the largest mass lynching in U.S. history took place—against Chinese immigrants. From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, scores of racist, xenophobic anti-Chinese laws were passed that unleashed mob violence. The 1871 Chinese Massacre started when a mob of around 500 attacked Chinese immigrants. Seventeen were hanged by the mob, after most had already been shot to death, and some mutilated. The city’s authorities did nothing to stop the carnage. Police chief Marshal Francis Baker made a brief appearance and then went home to bed, leaving the mob in charge. The city’s elite did act decisively on one front: making sure the lynchers put on trial were set free.

In 1910, the LAPD seized on the dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times Building, which was immediately blamed on “labor saboteurs,“ to compile records on at least 300,000 suspected “subversives” including sympathizers with the Mexican revolution.

During World War 1, suspected anarchists, socialists, and communists were hunted down by the LAPD and vigilantes and 220 were arrested under the Espionage Act.

In 1923, the LAPD began to infiltrate the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW, a radical workers’ group) and the Communist Party and in the ‘20s, and ‘30s LAPD Red Squads regularly broke up union and leftist meetings, beating up and arresting people.

The department’s first statistics, published in the 1920s, showed that the LAPD was disproportionately targeting Black and Brown youth for arrest.

In August of 1941 the LAPD began rounding up hundreds of “subversive” Japanese residents, even before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat, ordered their internment in concentration camps.

In 1941, two days after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the LAPD began rounding up hundreds of Japanese residents they labeled as "subversive," even before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat, ordered their internment in concentration camps.

In 1942, when José Gallardo Díaz was murdered, the LAPD rounded up 600 Latino youth, arrested 59, and convicted 17 (shown here) without one definitive witness or piece of evidence.

In 1942, when the body of José Gallardo Díaz was found near a swimming hole, the media dubbed it the “Sleepy Lagoon Murder,” and whipped up furor against “Mexican Boy Gangs” who were blamed for his death. The LAPD rounded up 600 Latino youth, arrested 59, and convicted 17 without the prosecution producing one definitive witness or piece of evidence.

On May 31, 1943, white servicemen in LA assaulted Mexican youth dressed in zoot suits while the LAPD stood by. Then LAPD arrested as many as 500 of the zoot suiters.

On May 31, 1943, 12 white sailors and servicemen fought with some Pachuco youth—Mexican gangs and others who adopted the oversized “zoot suit” as a sign of rebellion. Over the next several days, hundreds of white servicemen fanned out across LA looking for zoot suiters to attack, in what was called the “Zoot Suit Riots.” What did the LAPD do? It stood by as the Pachucos were being assaulted, then arrested as many as 500 of them! The LA Times, which helped create anti-Mexican hysteria with reports of “Mexican crime waves,” called the sailors’ actions “a great moral lesson” for the “freak” zoot suiters.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS:

LAPD police chief James Davis, during the Red Squad raids of “subversives” and labor union strikes of the 1920s-30s:

“The more the police beat them up and wreck their headquarters, the better. Communists have no constitutional rights…”

LAPD chief William Parker told his audience at his swearing-in ceremony in 1950, a time of major Black migration to L.A. from the South:

“Los Angeles is the white spot of the great cities of America today. It is to the advantage of the community that we keep it that way.”

Parker said of the 1965 Watts uprising;

“Like Monkeys in a Zoo. One threw a rock and the rest started throwing rocks.”

Afterwards, he warned:

“[I]t is estimated that by 1970, 45% of Los Angeles will be Negro…. If you want any protection for your home and family … you’re going to have to support a strong police department. If you don’t, God help you.”

LAPD chief Daryl Gates, following a string of LAPD “chokehold” killings of young Black men in custody. claimed that the deaths were the fault of the victims’ racial anatomy, not excessive police force:

“We may be finding that in some Blacks when [the carotid chokehold] is applied the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as they do on normal people.”

Daryl Gates, to critics of Operation Hammer:

“This is war.... we’re exceedingly angry.... We want to get the message out to the cowards out there, and that’s what they are, rotten little cowards -- we want the message to go out that we're going to come and get them….”

“I think people believe that the only strategy we have is to put a lot of police officers on the street and harass people and make arrests for inconsequential kinds of things. Well, that’s part of the strategy, no question about it.”

Testifying in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1990, Daryl Gates stated that

casual drug users “ought to be taken out and shot” because “we’re in a war” and even casual drug use is “treason.”

Editor’s note: Tyisha Miller was a 19-year-old African-American woman shot dead by Riverside, California police in 1998. Miller had been passed out in her car, resulting from a seizure, when police claimed that she suddenly awoke and had a gun; they fired 23 times at her, hitting her at least 12 times, and murdering her. Bob Avakian addressed this.

If you can’t handle this situation differently than this, then get the fuck out of the way. Not only out of the way of this situation, but get off the earth. Get out of the way of the masses of people. Because, you know, we could have handled this situation any number of ways that would have resulted in a much better outcome. And frankly, if we had state power and we were faced with a similar situation, we would sooner have one of our own people’s police killed than go wantonly murder one of the masses. That’s what you’re supposed to do if you’re actually trying to be a servant of the people. You go there and you put your own life on the line, rather than just wantonly murder one of the people. Fuck all this “serve and protect” bullshit! If they were there to serve and protect, they would have found any way but the way they did it to handle this scene. They could have and would have found a solution that was much better than this. This is the way the proletariat, when it’s been in power has handled—and would again handle—this kind of thing, valuing the lives of the masses of people. As opposed to the bourgeoisie in power, where the role of their police is to terrorize the masses, including wantonly murdering them, murdering them without provocation, without necessity, because exactly the more arbitrary the terror is, the more broadly it affects the masses. And that’s one of the reasons why they like to engage in, and have as one of their main functions to engage in, wanton and arbitrary terror against the masses of people.

—Bob Avakian, BAsics 2:16

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: