Kent State!

Originally posted May 16, 2010 | Reposted | revcom.us

Editors’ note: May 4 marks the 50th anniversary of Kent State, the assassination of four students by the Ohio National Guard, with import and relevance today. We are re-publishing excerpts of an article published on the occasion of the 40th anniversary. As we noted in concluding that original article:

May 1970 was a time when students were NOT complacent, passive, and complicit but dared, even at the cost of very real sacrifice, to stand up against and resist the crimes of their government, and the system that government serves and enforces—and there are very important lessons from this inspiring experience for today. It is time, once again, for students—and many others—to step up and join the movement we are building for revolution.

On this occasion, we highlight the following from Bob Avakian on the larger context and ethos of the 1960s:

Editor’s note: Here Bob Avakian talks about the 1960s.

Between the anti-war protesters and the war planners in the Pentagon; between the Black Panthers and J. Edgar Hoover; between Black, Latino, Asian, and Native peoples on the one side and the government on the other; between the women who rebelled against their “traditional” roles and the rich old men who ruled the country; between the youth who brought forward new music, in the broadest sense, and the preachers who denounced them as disciples of the devil and despoilers of civilization: the battle lines were sharply drawn. And through the course of those tumultuous times, those who were rebelling against the established order and the dominating relations and traditions increasingly found common cause and powerful unity; they increasingly gained—and deserved—the moral as well as political initiative, while the ruling class dug in and lashed out to defend its rule, but increasingly, and very deservedly, lost moral and political authority.

BAsics 5:6

* * * * *

Forty years ago, on May 4, 1970, four students at Kent State University were gunned down by the Ohio National Guard. Days before, on April 30, the U.S. had begun the invasion of Cambodia in Southeast Asia. This represented a major escalation in and expansion of the war in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. At the same time, Bobby Seale, a leader of the Black Panther Party, faced trumped up murder charges in New Haven, Connecticut. Thousands militantly protested against this outrage over the weekend of May 2-3.

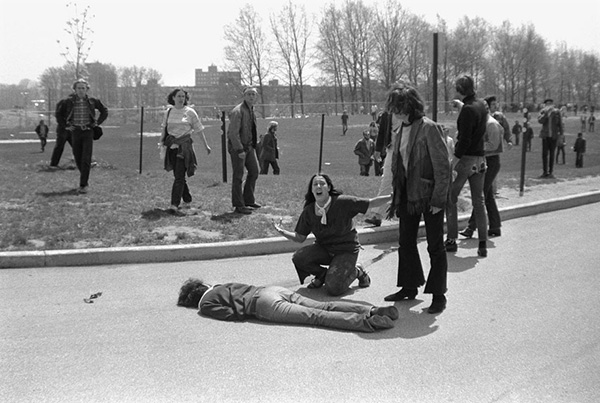

When the U.S. invaded Cambodia, students across the country poured into the streets and took over buildings in protest. In the months before this escalation of the war, protest on Ohio campuses had been developing, as students mobilized against the war and joined this with a movement of Black students. The governor had called in the National Guard to Miami University at Ohio in response to a building takeover there that was brutally repressed by the local police, and then again he mobilized the Guard at Kent State. In the face of the Guard forbidding the demonstration against the invasion of Cambodia, the students defiantly went ahead. Tear gas was fired. Students were pushed around. But still they refused to back down in the face of these attacks. Then, the Guard fired into the crowd (61-67 rounds in the space of 13 seconds), killing four students and wounding nine others, one paralyzed for life. Then 10 days later, two students were murdered and 12 others were wounded at Jackson State University in Mississippi.

Why did the students resist? What were students thinking? On campuses across the country (and more broadly in society), people were not thinking the war should be opposed because it was unnecessary, or detrimental, to U.S. national security interests. Students were not thinking that the financial cost of the war to Americans was too high. Their thought was not that maybe the U.S. shouldn’t have gone into Vietnam to begin with, but since it did, it had to stay and “rebuild” the country. People were not saying: “We think killing innocent civilians is probably wrong, but then again we are not there, so we can’t be sure.” And they were definitely not of a mind that the determination about whether the war in Vietnam was just should be left to the President and the U.S. generals, or any of the other assorted war criminals who were waging that war in the first place.

No, the leading edge of opposition to the Vietnam War—including among those tens of thousands of students who were at the forefront of resisting that war—was a clear and basic moral and political stand: the U.S. has no right whatsoever to be in Vietnam; it is visiting crimes against humanity on the people there, and we demand an immediate end to the war. Over years of resistance, this movement had spread from more radical campuses, like Berkeley and Columbia, and was penetrating deep into what the U.S. calls its heartland. On page 1 of The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, it plainly stated: “The crisis on American campuses has no parallel in the history of the nation. The crisis has roots in divisions of American society as deep as any since the Civil War.”

The Leap in the Situation and the Movement for Revolution

These were times of mass struggle and upheaval. The movement against the war came together with the movement against racial oppression and for Black liberation—all within the context of a much broader and sustained societal rebellion against oppressive relations and ideas. Defiance and a determination to fight for what was moral and just typified the resistance movements of that time. There was a flowering of movements of youth, like the hippies, who were thoroughly alienated from the traditional norms of society and searching for alternatives. And this brought them into increasing conflict with the powers-that-be and the system as a whole.

Distilled out of all this, a core emerged convinced of the need to fight for revolution. This was a core which opposed U.S. imperialism in an all round way—and drew the connections between the crimes of the imperialist system committed throughout the world and the crimes that this system committed in the U.S. This core worked tirelessly to show that it was the capitalist-imperialist system based on the exploitation of the vast majority of people on this planet that was at the root of the oppression—the U.S. war in Southeast Asia, the oppression of Black, Latino, and other minorities, the oppression of women, and the many other horrors people were resisting. They did not see their interests as lying with the interests of U.S. capitalism (at home and abroad), nor did they act as though they had a stake in protecting and defending that system. Instead, this core brought to the broader thousands of students, who opposed injustice and war and felt completely alienated from their government, the understanding that the system itself was the evil that needed to be done away with. And they fought with all their fiber to build the revolutionary movement with that goal in mind. Internationalist in their outlook, they were inspired by and supported revolutionary movements throughout the world. And they especially looked to China, which was a genuine socialist country at that time, led by Mao Tsetung.

All this set the stage for May 1970. When the U.S. army invaded Cambodia, which President Dick Nixon had promised NOT to do, broad swaths of society opposed to the war joined the movement. And those who had been resisting became all the more determined to stand up and put an end to this war.

With the killing of the students at Kent State and Jackson State, about 4 million students at 1,350 universities, outraged by the murders, took to the streets in protest.*

Campuses across the country shut down. There was a leap in the situation, and many who had been sickened by the war—and the treatment of Black people in this society—but passive, sprang into action. They confronted the forces of the state, refusing to back down in the face of this brutal repression. And began to look at things in new ways. For hundreds of thousands, the very legitimacy of the current order’s right to rule was called into question. The political polarization in society changed, seemingly overnight. And within this outpouring of people across the country, the revolutionary core gained in strength... many, many people were radicalized and the target of the uncompromising protest became the system itself... the revolutionary movement, while still far from encompassing the majority in society, had the initiative in many ways.

* Kenneth Heineman, Put Your Bodies Upon the Wheels: Student Revolt in the 1960s, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001; page 176. [back]

May 4, 1970 - U.S. National Guard shoot dead four unarmed students and wound nine at Kent State University. The students were protesting the Vietnam War. (AP photo)

May 4, 1970 - The National Guard at Kent State University. (AP photo)

May 4, 1970 - Kent State University student hurling a tear gas cannister back towards National Guardsmen.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: