Case #12: The 1921 Tulsa Massacre and the Destruction of Black Wall Street

| revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.” (See “3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.”)

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907 coincided with the discovery of oil, and the boom years that followed saw its population grow from 10,000 in 1910 to 100,000 a decade later. This included a significant number of Black people, looking for a better life, and hoping to escape the worst of Jim Crow Mississippi, Georgia, and other states of the Old South. In 1921, Tulsa was strictly segregated; Black people could work in town, but all Black residents were required to live and shop in the Greenwood District of Northern Tulsa. In time, Greenwood’s segregated economy, self-contained and self-sufficient, was so successful that it became known nationally as the “Black Wall Street.” About 11,000 Black residents lived in the Greenwood neighborhood. Black-owned grocery stores, banks, libraries, hotels, restaurants, movie theaters, and more lined Greenwood Avenue.

THE CRIME

On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner working downtown, entered the elevator of the only building with a restroom Blacks could use in the area. Sarah Page, a white 17-year-old, was the elevator operator. When the door closed, Page cried out, and Rowland ran off. The most common explanation is that Rowland just stepped on Page’s foot. But Rowland was alleged—without evidence—to have assaulted Page. He was arrested the next morning and held in a jail cell above City Hall.

That afternoon, the Tulsa Tribune ran the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” suggesting that Page had been raped, and editorialized: “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” Within an hour of the paper hitting the streets a lynch mob in the hundreds descended on the courthouse.

Word spread throughout Greenwood that whites were storming the courthouse and Rowland was in danger. After debating how to respond, at 9 pm a group of 25 armed Black men, some veterans of World War 1, drove to the courthouse determined to stop the lynching. They got out with their rifles and shotguns, and offered their support to the local authorities. Their offer was refused, and they left.

But the white mob was incensed, and grew into the thousands in no time as word spread, more and more coming with weapons. At 10 pm a group of 75 Black men returned to the courthouse after new rumors that a lynching was imminent. They marched single file to the courthouse steps. Again, their offer of help to protect Rowland was refused. A white man approached an armed Black army veteran and demanded he turn over his gun. A fight broke out, and a gun went off.

Historian and author Scott Ellsworth wrote: “While the first shot fired at the court house may have been unintentional, those that followed were not. Almost immediately, members of the white mob—and possibly some law enforcement officers—opened fire on the African American men, who returned volleys of their own. The initial gunplay lasted only a few seconds, but when it was over, as many as a dozen men, both black and white, lay dead or wounded. Out numbered more than twenty-to-one, the black men began a retreating fight toward the African American district, with armed whites in close pursuit.”1

“They tried to kill all the black folks they could see,” a survivor, George Monroe, recalled in the 1999 documentary The Night Tulsa Burned.

Shortly after the fighting broke out at the courthouse, a large number of whites—many who’d been part of the lynch mob—gathered outside police headquarters nearby. There, as many as 500 white men and boys were sworn in as “Special Deputies” and told to “Get a gun and get a nigger.” Weapons were passed out by other deputies from a sporting goods store across the street. White rioters began firing on Blacks and setting fire to Black-owned homes and businesses late into the night.

“Tuesday night, May 31, was the riot, and Wednesday morning, by day break, was the invasion.” (Unidentified observer to a reporter)

As dawn approached, thousands of armed whites—some estimated as many as 10,000—gathered in three locations on the edges of Greenwood. A siren sounded at daybreak, and the mobs of white terrorists launched their invasion.

These armed white mobs included over 150 Tulsa police. They set about systematically killing, looting, and burning the entire district of Greenwood, block by block. Armed whites broke into Black homes and businesses and forced the people outside, where they were led away at gunpoint to internment centers set up by the authorities. Anyone who resisted was shot. If guns were found inside, the occupant was shot. The homes and businesses were looted, then set on fire with torches and oil-soaked rags. House by house, block by block, Greenwood was demolished. Airplanes were used to shoot Black people from the air and drop kerosene bombs on buildings, setting them ablaze.

Throughout this assault, Black Tulsans, while tremendously outnumbered, fought back. Riflemen took positions atop the belfry of a newly built church to temporarily halt the advance of the white invasion. But the church was burned to the ground. These attempts at resistance could not be maintained because the deputized police and the National Guard units arrested 6,000 Greenwood residents. Black Tulsans did not go down without a fight, but they were out-gunned and out-numbered. “Survivors recounted black bodies loaded on trains and dumped off bridges into the Arkansas River and, most frequently, tossed into mass graves.”2

By noon on June 1, these white mobs had murdered more than 300 Black Tulsa residents. They had turned 40 square blocks of Greenwood into a scorched wasteland. This included 1,256 homes destroyed, along with virtually every other structure—including churches, schools, businesses, even a hospital and library. “Not one of these criminal acts was then or ever has been prosecuted or punished by government at any level, municipal, county, state, or federal.” (Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921)

After order was restored, the Black people who’d been detained were released, but only if signed for by a white person, who also had to agree to accept responsibility for that detainee’s subsequent behavior. More than 10,000 residents were left homeless. Thousands of Black Tulsans spent the winter living in tents. Many left for good, having had enough of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

THE CRIMINALS

The racist mobs of thousands of white Tulsans were directly responsible for the horror inflicted on the people of Greenwood.

The Tulsa police chief and Tulsa deputies had a direct hand in arming, deputizing, and directing the mobs from the very start of the killing of Black Tulsans.

The Tulsa city officials played a decisive role by refusing to take any action to stop the racial massacre. And shortly afterwards, these same officials passed a zoning ordinance that made it too expensive for the Greenwood residents to rebuild their homes.

The local units of the National Guard, by arresting every Black resident of Tulsa they could find and taking them into “protective custody,” left Greenwood property unprotected and aided the “special deputies” who came to burn it. The after-action reports by the local guardsmen show they saw their job not as protecting the people of Greenwood, but putting down the supposed “Negro uprising.”

The Oklahoma State Troopers did not arrive from Oklahoma City until the annihilation of Greenwood was over; arriving earlier could have prevented some of the worst crimes from taking place.

The governor of Oklahoma, from the very start, treated the events in Tulsa as a Black “insurrection.”

The extent of the Ku Klux Klan’s involvement and possible lead role in this heinous act of terror hasn’t been proved, but “Tulsa’s atmosphere reeked with a Klan-like stench that oozed through the robes of the Hooded Order.” (Tulsa Race Riot report.) At that time many of the city’s most prominent men were Klansmen, including the lawyer assigned to represent Dick Rowland. Photographs of the Tulsa massacre were made into postcards, including a close-up of a charred Black body; and another of the Greenwood District in ruins.

THE ALIBI

The blame for the Tulsa Massacre was, from the very start, fully put on Greenwood’s Black residents—calling it a “Negro Uprising,” or “Insurrection.” A grand jury investigation organized by Oklahoma’s governor in the days after the massacre concluded:

We find that the recent race riot was the direct result of an effort on the part of a certain group of colored men who appeared at the court house on the night of May 31, 1921, for the purpose of protecting one Dick Rowland ...There was no mob spirit among the whites, no talk of lynching and no arms. The assembly was quiet until the arrival of armed Negroes, which precipitated and was the direct cause of the entire affair.

THE REAL MOTIVE

The economic success of the people of Black Tulsa—including home, business, and land ownership—fueled resentment, fear, and jealousy within the white community. Many of Greenwood’s Black residents were living more successful lives than white Tulsans. In a community, and a country, where white supremacy was taken for granted—and counted on—the success of the people of Greenwood was seen as a provocation.

The Tulsa Massacre, and the 1919 “Red Summer” of anti-Black violence that preceded it (see American Crime Case #15), took place at a time when the U.S. rulers needed to maintain the brutal oppression of Black people and white supremacy under changing conditions. The beginning of the Great Migration saw Black people leaving the rural South to find work in the cities of the North. Among them were Black veterans of World War 1, returning with a defiant spirit and less willingness to put up with open Jim Crow degradation and terror. Those in power faced the “need” for Black people to be beaten into submission through terror, their defiant spirit suppressed, and white people (including oppressed white people) enlisted to serve and identify with the exploitative, white supremacist order.

Resources:

- Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the published findings of an independent expert panel on the consequences of the massacre.

- The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims, by B.C. Franklin, an unpublished manuscript written 10 years after the massacre by a witnessing survivor.

- Black Wall Street: The African American Haven That Burned and Then Rose From the Ashes, by Victor Luckerson, a reported, researched look at the glory, razing, and rebuilding of Greenwood.

- Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, by Scott Ellsworth, the first comprehensive history of the events leading up to, during, and after the massacre.

- ‘They was killing black people’, by DeNeen L. Brown, a reported article about the lingering damages of the massacre, and how it affects Tulsa today, Washington Post, September 28, 2019.

- In Search of History—The Night Tulsa Burned, History Channel Documentary

1. “The Tulsa Race Riot,” by Dr. Scott Ellsworth, an essay in Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. [back]

2. Washington Post, September 18, 2018. [back]

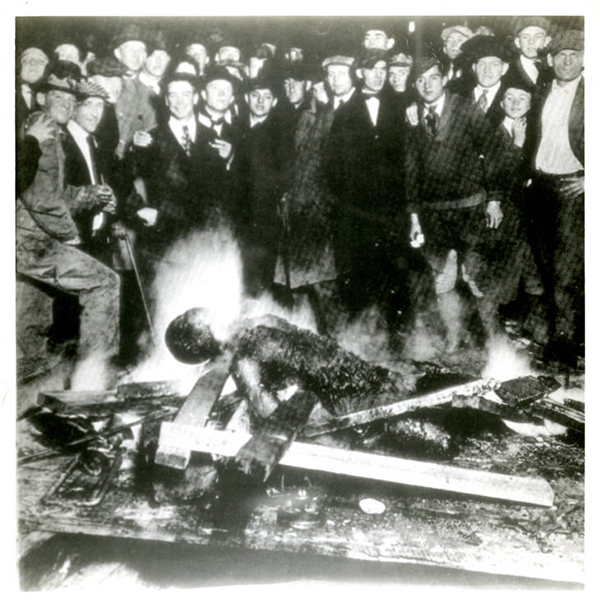

Systematic killing, looting, and burning of the entire district of Greenwood during Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921.

House by house, block by block, Greenwood, Tulsa was demolished.

A black man being burned on a bed of lumber during the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. Photo: Unsourced Archive

Mt. Zion Baptist Church burns during Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. Photo: Historical Society and Museum

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: