Among the most distinguishing features of today’s situation are the leaps that are occurring in globalization, linked to an accelerating process of capitalist accumulation in a world dominated by the capitalist-imperialist system. This has led to significant, and often dramatic, changes in the lives of huge numbers of people, often undermining traditional relations and customs. Here I will focus on the effects of this in the Third World—the countries of Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East—and the ways in which this has contributed to the current growth of religious fundamentalism there.

Throughout the Third World people are being driven in the millions each year away from the farmlands, where they have lived and tried to eke out an existence under very oppressive conditions but now can no longer do even that: they are being thrown into the urban areas, most often into the sprawling shantytowns, ring after ring of slums, that surround the core of the cities. For the first time in history, it is now the case that half of the world’s population lives in urban areas, including these massive and ever-growing shantytowns.

Being uprooted from their traditional conditions—and the traditional forms in which they have been exploited and oppressed—masses of people are being hurled into a very insecure and unstable existence, unable to be integrated, in any kind of “articulated way,” into the economic and social fabric and functioning of society. In many of these Third World countries, a majority of the people in the urban areas work in the informal economy—for example, as small-scale peddlers or traders, of various kinds, or in underground and illegal activity. To a significant degree because of this, many people are turning to religious fundamentalism to try to give them an anchor, in the midst of all this dislocation and upheaval.

An additional factor in all this is that, in the Third World, these massive and rapid changes and dislocations are occurring in the context of domination and exploitation by foreign imperialists—and this is associated with “local” ruling classes which are economically and politically dependent on and subordinate to imperialism, and are broadly seen as the corrupt agents of an alien power, who also promote the “decadent culture of the West.” This, in the short run, can strengthen the hand of fundamentalist religious forces and leaders who frame opposition to the “corruption” and “Western decadence” of the local ruling classes, and the imperialists to which they are beholden, in terms of returning to, and enforcing with a vengeance, traditional relations, customs, ideas and values which themselves are rooted in the past and embody extreme forms of exploitation and oppression.

Where Islam is the dominant religion—in the Middle East but also countries such as Indonesia—this is manifested in the growth of Islamic fundamentalism. In much of Latin America, where Christianity, particularly in the form of Catholicism, has been the dominant religion, the growth of fundamentalism is marked by a situation where significant numbers of people, in particular poor people, who have come to feel that the Catholic Church has failed them, are being drawn into various forms of protestant fundamentalism, such as Pentecostalism, which combines forms of religious fanaticism with a rhetoric that claims to speak in the name of the poor and oppressed. In parts of Africa as well, particularly among masses crowded into the shantytown slums, Christian fundamentalism, including Pentecostalism, has been a growing phenomenon, at the same time as Islamic fundamentalism has been growing in other parts of Africa.1

But the rise of fundamentalism is also owing to major political changes, and conscious policy and actions on the part of the imperialists in the political arena, which have had a profound impact on the situation in many countries in the Third World, including in the Middle East. As one key dimension of this, it is very important not to overlook or to underestimate the impact of the developments in China since the death of Mao Tsetung and the complete change in that country, from one that was advancing on the road of socialism to one where in fact capitalism has been restored and the orientation of promoting and supporting revolution, in China and throughout the world, has been replaced by one of seeking to establish for China a stronger position within the framework of world power politics dominated by imperialism. This has had a profound effect—negatively—in undermining, in the shorter term, the sense among many oppressed people, throughout the world, that socialist revolution offered the way out of their misery and in creating more ground for those, and in particular religious fundamentalists, who seek to rally people behind something which in certain ways is opposing the dominant oppressive power in the world but which itself represents a reactionary worldview and program.

This phenomenon is reflected in the comments of a “terrorism expert” who observed about some people recently accused of terrorist acts in England that, a generation ago, these people would have been Maoists. Now, despite the fact that the aims and strategy, and the tactics, of genuine Maoists—people guided by communist ideology—are radically different from those of religious fundamentalists and that communists reject, in principle, terrorism as a method and approach, there is something real and important in this “terrorism expert’s” comments: a generation ago many of the same youths and others who are, for the time being, drawn toward Islamic and other religious fundamentalisms, would instead have been drawn toward the radically different, revolutionary pole of communism. And this phenomenon has been further strengthened by the demise of the Soviet Union and the “socialist camp” that it headed. In reality, the Soviet Union had ceased to be socialist since the time, in the mid-1950s, when revisionists (communists in name but capitalists in fact) seized the reins of power and began running the country in accordance with capitalist principles (but in the form of state capitalism and with a continuing “socialist” camouflage). But by the 1990s, the leaders of the Soviet Union began to openly discard socialism, and then the Soviet Union itself was abolished and Russia and the other countries that had been part of the Soviet “camp” abandoned any pretense of “socialism.”

All this—and, in relation to it, a relentless ideological offensive by the imperialists and their intellectual camp followers—has led to the notion, widely propagated and propagandized, of the defeat and demise of communism and, for the time being, the discrediting of communism among broad sections of people, including among those restlessly searching for a way to fight back against imperialist domination, oppression and degradation.2

But it is not only communism that the imperialists have worked to defeat and discredit. They have also targeted other secular forces and governments which, to one degree or another, have opposed, or objectively constituted obstacles to, the interests and aims of the imperialists, particularly in parts of the world that they have regarded as of strategic importance. For example, going back to the 1950s, the U.S. engineered a coup that overthrew the nationalist government of Mohammad Mossadegh in Iran, because that government’s policies were viewed as a threat to the control of Iran’s oil by the U.S. (and secondarily the British) and to U.S. domination of the region more broadly. This has had repercussions and consequences for decades since then. Among other things, it has contributed to the growth of Islamic fundamentalism and the eventual establishment of an Islamic Republic in Iran, when Islamic fundamentalists seized power in the context of a mass upheaval of the Iranian people in the late 1970s, which led to the overthrow of the highly repressive government of the Shah of Iran, who had been backed and in fact maintained in power by the U.S. since the ouster of Mossadegh.3

In other parts of the Middle East, and elsewhere, over the past several decades the imperialists have also consciously set out to defeat and decimate even nationalist secular opposition; and, in fact, they have at times consciously fed the growth of religious fundamentalist forces. Palestine is a sharp example of this: Islamic fundamentalist forces there were actually aided by Israel—and the U.S. imperialists, for whom Israel acts as an armed garrison—in order to undermine the more secular Palestine Liberation Organization. In Afghanistan, particularly during the Soviet occupation of that country in the 1980s, the U.S. backed and provided arms to the Islamic fundamentalist Mujahadeen, because it was recognized that they would be fanatical fighters against the Soviets. Other forces, including not only more secular nationalists but Maoists, opposed the Soviet occupation and the puppet governments it installed in Afghanistan, but of course the Maoists in particular were not supported by the U.S., and in fact many of them were killed by the “Jihadist” Islamic fundamentalists that the U.S. was aiding and arming.

In Egypt, going back to the 1950s, there was the whole phenomenon of the popular nationalist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, and of “Nasserism,” a form of Arab nationalism which wasn’t limited to Egypt but whose influence was very widespread after Nasser came to power in Egypt. In 1956 a crisis developed when Nasser acted to assert more control over the Suez Canal; and Israel, along with France and England—still not fully resigned to the loss of their large colonial empires—moved together in opposition to Nasser. Now, as an illustration of the complexity of things, in that “Suez crisis,” the U.S. opposed Israel, France and Britain. The U.S. motive was not to support Arab nationalism or Nasser in particular, but to further supplant the European imperialists who had previously colonized these parts of the world. To look briefly at the background of this, in the aftermath of World War 1, with the defeat of the old Ottoman Empire, centered in Turkey, France and England basically divided up the Middle East between them—some of it was allotted to the French sphere of influence, as essentially French colonies, and other parts were under British control. But then after World War 2—through which Japan as well as Germany and Italy were thoroughly defeated, and countries like France and Britain were weakened, while the U.S. was greatly strengthened—the U.S. moved to create a new order in the world and, as part of that, to impose in the Third World, in place of the old-line colonialism, a new form of colonialism (neo-colonialism) through which the U.S. would maintain effective control of countries and their political structures and economic life, even where they became formally independent. And, as part of this, Israel was made to find its place in relation to the now more fully realized and aggressively asserted American domination in the Middle East.

But, out of his stand in what became the “Suez crisis,” and as a result of other nationalist moves, Nasser and “Nasserism” developed a widespread following in the Arab countries in particular. In this situation, the U.S., while not seeking overtly to overthrow Nasser, worked to undermine Nasserism and generally more secular forces—including, obviously, communist forces—that were opposed to, or stood in the way of, U.S. imperialism. And, especially after the 1967 war, in which Israel defeated surrounding Arab states and seized additional Palestinian territory (now generally referred to as the “occupied territories,” outside of the state of Israel which itself rests on land stolen from the Palestinians), Israel has been firmly backed by and has acted as a force on behalf of U.S. imperialism.

Defeat at the hands of Israel in the 1967 war contributed significantly to a decline in the stature and influence of Nasser and Nasserism—and similar, more or less secular, leaders and trends—among the people in the Middle East; and by the time of his death in 1970, Nasser had already begun to lose a significant amount of his luster in the eyes of the Arab masses.

Here again we can see another dimension to the complexity of things. The practical defeats and failure of Nasser had the effect of undermining, in the eyes of increasing numbers of people, the legitimacy, or viability, of what Nasser represented ideologically. Now, the fact is that “Nasserism” and similar ideological and political trends, do not represent, and cannot lead to, a thorough rupture with imperialist domination and all forms of the oppression and exploitation of the people. But that is something which has to be, and is in fact, established by a scientific analysis of what is represented by such ideologies and programs and what they aim to achieve, and are actually capable of achieving; it is not proven by the fact that, in certain particular instances or even over a certain limited period of time, the leaders personifying and seeking to implement such ideologies and programs suffer setbacks and defeats. In the ways in which masses of people in the Arab countries (and more broadly) responded to such setbacks and defeats, on the part of Nasser and those more or less representing the same ideology and program, there was a definite element of pragmatism—the notion that, even in the short run, what prevails is true and good, and what suffers losses is flawed and bankrupt. And, of course, a spontaneous tendency toward such pragmatism, among the masses of people, has been reinforced by the verdicts pronounced by the imperialists and other reactionaries—not only, of course, in relation to secular forces such as Nasser but, even more so, in relation to communists and communism, which represent a much more fundamental opposition to imperialism and reaction.

In all this it is important to keep in mind that over a number of decades, and at least until very recently, the U.S. and Israel have worked to undermine secular forces among the opposition to them in the Middle East (and elsewhere) and have at least objectively favored, where they have not deliberately fostered, the growth of Islamic fundamentalist forces. During the “Cold War,” this was, to a significant degree, out of a calculation that these Islamic fundamentalists would be much less likely to align themselves with the Soviet camp. And, to no small degree, this favoring of religious fundamentalists over more secular forces has been motivated by the recognition of the inherently conservative, indeed reactionary, essence of this religious fundamentalism, and the fact that, to a significant degree, it can act as a useful foil for the imperialists (and Israel) in presenting themselves as an enlightened, democratic force for progress.

Now, one of the ironies of this whole experience is that Nasser, and other Arab nationalist heads of state, viciously and murderously suppressed not only Islamic fundamentalist opposition (such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt) but also communists. But, with what has taken place on the world stage, so to speak, in recent decades—including what has happened in China and the Soviet Union (as discussed above) and the widely propagated verdict that this represents the “defeat” of communism; the seizure of power in Iran by Islamic fundamentalists, with the fall of the Shah of Iran in the late 1970s; the resistance to the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan, which by the late 1980s forced a Soviet withdrawal and contributed significantly to the downfall of the Soviet Union itself; and the setbacks and defeats for more or less secular rulers like Nasser (and more recently someone like Saddam Hussein) in the Middle East and elsewhere—it has, in the short term, been the Islamic fundamentalists, much more than revolutionaries and communists, who have been able to regroup, and to experience a significant growth in influence and organized strength.

Another example of this whole trajectory, from the 1950s to the present time—which illustrates, in very stark and graphic terms, the points being made above—is the country of Indonesia. During the 1950s and 1960s Indonesia had the third largest communist party in the world (only in the Soviet Union and China were the communist parties larger). The Indonesian Communist Party had a massive following among the poor in the urban areas (whose slums, in the city of Jakarta and elsewhere, were already legendary, in the negative sense) as well as among the peasants in the countryside and sections of the intellectuals and even some more nationalist bourgeois strata. Unfortunately, the Indonesian Communist Party also had a very eclectic line—a mixed bag of communism and revisionism, of seeking revolutionary change but also trying to work through parliamentary means within the established government structures.

The government at that time was headed by the nationalist leader Achmed Sukarno. Now, an important insight into this was provided as part of a visit I made to China in the 1970s, during which some members of the Chinese Communist Party talked about the experience of the Indonesian Communist Party, and they specifically recounted: We used to struggle with comrade Aidit (the head of the Indonesian Communist Party during the period of Sukarno’s government); we warned him about what could happen as a result of trying to have one foot in communism and revolution and one foot in reformism and revisionism. But the Indonesian Communist Party persisted on the same path, with its eclectic approach; and in 1965 the U.S., through the CIA, working with the Indonesian military and a leading general, Suharto, carried out a bloody coup, in which hundreds of thousands of Indonesian communists, and others, were massacred, the Communist Party of Indonesia was thoroughly decimated, and at the same time Sukarno was ousted as the head of government and replaced by Suharto.

In the course of this coup, the rivers around Jakarta became clogged with the bodies of the victims: the reactionaries would kill people, alleged or actual communists, and throw their bodies, in massive numbers, into the rivers. And, in a phenomenon that is all too familiar, once this coup—which the CIA led, organized and engineered—was unleashed and carried out, all kinds of people who were involved in personal or family disputes and feuds would start accusing other people of being communists and turning them into the authorities, with the result that a lot of people who weren’t even communists got slaughtered, along with many who were. Once the imperialists and reactionaries unleashed this blood-letting, this encouraged and gave impetus to, and swept many people up in, a kind of bloodlust of revenge. The CIA openly brags about how they not only organized and orchestrated this coup but also specifically targeted several thousand of the leading communists and got rid of them directly, within this larger massacre of hundreds of thousands.

The fundamental problem with the strategy of the Indonesian Communist Party was that the nature of the state—and in particular the military—had not changed: the parliament was to a large degree made up of nationalists and communists, but the state was still in the hands of the reactionary classes; and because their control of the state had never been broken, and the old state apparatus in which they maintained control was never shattered and dismantled, Suharto and other reactionary forces were able, working together with and under the direction of the CIA, to pull off this bloody coup, with its terrible consequences.

In this regard, another anecdote that was recounted by members of the Chinese Communist Party is very telling and poignant. They told a story about how Sukarno had a scepter that he used to carry around, and the Chinese officials who met with him asked him, “What is this scepter you carry around?” And Sukarno replied: “This scepter represents state power.” Well, the Chinese comrades telling this story summed up, after the coup “Sukarno still had the scepter, they let him keep that, but he didn’t have any state power.”

The Indonesian Communist Party was all but totally wiped out, physically—its membership was virtually exterminated, with only a few remnants of it here and there—a devastating blow from which it has never recovered. And the decimation was not only in literal and physical terms but also was expressed in ideological and political defeat, disorientation and demoralization. Over the decades since then, what has happened in Indonesia? One of the most striking developments is the tremendous growth of Islamic fundamentalism in Indonesia. The communist alternative was wiped out. In its place—in part being consciously fostered by the imperialists and other reactionary forces, but partly growing on its own momentum in the context where a powerful secular and, at least in name, communist opposition had been destroyed—Islamic fundamentalism filled the vacuum that had been left by the lack of a real alternative to the highly oppressive rule of Suharto and his cronies that was installed and kept in power for decades by the U.S.4

All this—what has taken place in Indonesia, as well as in Egypt, Palestine and other parts of the Middle East—is a political dimension which has been combined with the economic and social factors mentioned above—the upheaval and volatility and rapid change imposed from the top and seemingly coming from unknown and/or alien and foreign sources and powers—to undermine and weaken secular, including genuinely revolutionary and communist, forces and to strengthen Islamic fundamentalism (in a way similar to how Christian fundamentalism has been gaining strength in Latin America and parts of Africa).

This is obviously a tremendously significant phenomenon. It is a major part of the objective reality that people throughout the world who are seeking to bring about change in a progressive direction—and still more those who are striving to achieve truly radical change guided by a revolutionary and communist outlook—have to confront and transform. And in order to do that, it is necessary, first of all, to seriously engage and understand this reality, rather than remaining dangerously ignorant of it, or adopting an orientation of stubbornly ignoring it. It is necessary, and indeed crucial, to dig down beneath the surface of this phenomenon and its various manifestations, to grasp more deeply what are the underlying and driving dynamics in all this—what are the fundamental contradictions and what are the particular expressions of fundamental and essential contradictions, on a world scale and within particular countries and regions in the world—that this religious fundamentalism is the expression of, and how, on the basis of that deeper understanding, a movement can be developed to win masses of people away from this and to something which can actually bring about a radically different and much better world.

Rejecting the “Smug Arrogance of the Enlightened”

There is a definite tendency among those who are “people of the Enlightenment,” shall we say—including, it must be said, some communists—to fall into what amounts to a smugly arrogant attitude toward religious fundamentalism and religion in general. Because it seems so absurd, and difficult to comprehend, that people living in the 21st century can actually cling to religion and in fact adhere, in a fanatical and absolutist way, to dogmas and notions that are clearly without any foundation in reality, it is easy to dismiss this whole phenomenon and fail to recognize, or to correctly approach, the fact that this is indeed taken very seriously by masses of people. And this includes more than a few people among the lower, deeper sections of the proletariat and other oppressed people who need to be at the very base and bedrock of—and be a driving force within—the revolution that can actually lead to emancipation.

It is a form of contempt for the masses to fail to take seriously the deep belief that many of them have in religion, including religious fundamentalism of one kind or another, just as tailing after the fact that many believe in these things and refusing to struggle with them to give this up is also in reality an expression of contempt for them. The hold of religion on masses of people, including among the most oppressed, is a major shackle on them, and a major obstacle to mobilizing them to fight for their own emancipation and to be emancipators of all humanity—and it must be approached, and struggled against, with that understanding, even as, at any given time, it is necessary, possible, and crucial, in the fight against injustice and oppression, to unite as broadly as possible with people who continue to hold religious beliefs.

The Growth of Religion and Religious Fundamentalism:

A Peculiar Expression of a Fundamental Contradiction

Another strange, or peculiar, expression of contradictions in the world today is that, on the one hand, there is all this highly developed technology and sophisticated technique in fields such as medicine and other spheres, including information technology (and, even taking account that large sections of the population in many parts of the world, and significant numbers even within the “technologically advanced” countries, still do not have access to this advanced technology, growing numbers of people actually do have access to the Internet and to the extensive amounts of information available through the Internet, and in other ways) and yet, at the same time, there is the tremendous growth of, let’s call it what it is: organized ignorance, in the form of religion and religious fundamentalism in particular. This appears as not only a glaring but a strange contradiction: so much technology and knowledge on the one hand, and yet on the other hand so much widespread ignorance and belief in, and retreat into, obscurantist superstition.

Well, along with analyzing this in terms of the economic, social and political factors that have given rise to this (to which I have spoken above) another, and even more basic, way of understanding this is that it is an extremely acute expression in today’s world of the fundamental contradiction of capitalism: the contradiction between highly socialized production and private (capitalist) appropriation of what is produced.

Where does all this technology come from? On what basis has it been produced? And speaking specifically of the dissemination of information, and the basis for people to acquire knowledge—what is that founded on? All the technology that exists—and, for that matter, the wealth that has been created—has been produced in socialized forms by millions and millions of people through an international network of production and exchange; but all this takes place under the command of a relative handful of capitalists, who appropriate the wealth produced—and appropriate the knowledge produced as well—and bend it to their purposes.

What is this an illustration of? It is, for one thing, a refutation of the “theory of the productive forces,” which argues that the more technology you have, the more enlightenment there will be, more or less directly in relation to that technology—and which, in its “Marxist” expression, argues that the greater the development of technology, the closer things will be to socialism or to communism. Well, look around the world. Why is this not the case? Because of a very fundamental fact: All this technology, all the forces of production, “go through,” and have to “go through,” certain definite production relations—they can be developed and utilized only by being incorporated into what the prevailing ensemble of production relations is at any given time. And, in turn, there are certain class and social relations that are themselves an expression of (or are in any case in general correspondence with) the prevailing production relations; and there is a superstructure of politics, ideology and culture whose essential character reflects and reinforces all those relations. So, it is not a matter of productive forces—including all the technology and knowledge—just existing in a social vacuum and being distributed and utilized in a way that is divorced from the production relations through which it is developed and employed (and the corresponding class and social relations and superstructure). This takes place, and can only take place, through one or another set of production, social and class relations, with the corresponding customs, cultures, ways of thinking, political institutions, and so on.

In the world today, dominated as it is by the capitalist-imperialist system, this technology and knowledge is “going through” the existing capitalist and imperialist relations and superstructure, and one of the main manifestations of this is the extremely grotesque disparity between what is appropriated by a tiny handful—and a lesser amount that is meted out to broader strata in some of the imperialist countries, in order to stabilize those countries and to mollify and pacify sections of the population who are not part of the ruling class there—while amongst the great majority of humanity there is unbelievable poverty and suffering and ignorance. And, along with this profound disparity, we are witnessing this peculiar contradiction between so much technology and so much knowledge, on the one hand, and yet such widespread belief in, and retreat into, obscurantist superstition, particularly in the form of religious fundamentalism—all of which is in fact an expression of the fundamental contradiction of capitalism.

This is an extremely important point to understand. If, instead of this understanding, one were to proceed with a more linear approach and method, it would be easy to fall into saying: “I don’t get it, there is all this technology, all this knowledge, why are so many people so ignorant and so mired in superstition?” Once again, the answer—and it is an answer that touches on the most fundamental of relations in the world—is that it is because of the prevailing production, social and class relations, the political institutions, structures, and processes, and the rest of the superstructure—the prevailing culture, the ways of thinking, the customs, habits, and so on, which correspond to and reinforce the system of capitalist accumulation, as this finds expression in the era where capitalism has developed into a worldwide system of exploitation and oppression.

This is another important perspective from which to understand the phenomenon of religious fundamentalism. The more this disparity grows, the more there is a breeding ground for religious fundamentalism and related tendencies. At the same time, and in acute contradiction to this, there is also a potentially more powerful basis for revolutionary transformation. All of the profound disparities in the world—not only in terms of conditions of life but also with regard to access to knowledge—can be overcome only through the communist revolution, whose aim is to wrest control of society out the hands of the imperialists and other exploiters and to advance, through the increasingly conscious initiative of growing numbers of people, to achieve (in the formulation of Marx) the elimination of all class distinctions, all the production relations on which these class distinctions rest, all the social relations that correspond to those production relations, and the revolutionization of all the ideas that correspond to those social relations—in order to bring about, ultimately and fundamentally on a world scale, a society of freely associating human beings, who consciously and voluntarily cooperate for the common good, while also giving increasing scope to the initiative and creativity of the members of society as a whole.

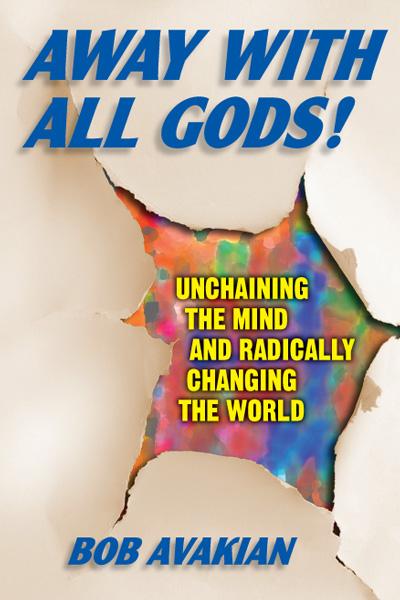

"Away with All Gods! is a powerful and erudite critique of religion and superstition and a rousing call to place our trust in reason and the scientific method....Unusual for an atheist work and in marked difference to works of Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins Avakian went further to explore the way in which religion is used to sustain the status quo and as a reactionary force by political power mongers...He stands against not only religion and superstition but for reason and science and shows us what an alternative way of living can really be like. More importantly he shows us the revolutionary potential of finally doing away with all gods and what such a new world could look like."

— Synergy Magazine

Available from Insight Press.