Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.”

3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better:

1) People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.

2) People have to dig seriously and scientifically into how this system of capitalism-imperialism actually works, and what this actually causes in the world.

3) People have to look deeply into the solution to all this.

Bob Avakian

May 1st, 2016

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

Paratroopers were set loose to raid homes, to beat, bayonet, shoot, torture and murder protesters and even bystanders on the streets. (Photo: AP)

THE CRIME

From May 18-27, 1980 the U.S.-backed South Korean military junta of President Chun Doo Hwan massacred as many as 2,000 courageous protesters in the major city of Kwangju (also spelled Gwangju). The U.S. publicly deplored the mass murder and repeatedly claimed it had nothing to do with it. But secretly behind the scenes, it was fully backing and enabling this slaughter.

After the 1950-53 Korean War, South Korea had been ruled by a series of brutal military dictatorships—from 1961-1979 by General Park Chung Hee. All had U.S. support. In 1979, amid a wave of student and mass protests, Park was assassinated. Two months later Gen. Chun Doo Hwan seized power in a coup and declared martial law.

Yet protests continued, demanding democratic rights, with university students and others demanding an end to “the arrests of dissidents and their families and friends, fraudulent elections, torture and unmet social needs.”1

By early May 1980, there were daily demonstrations of tens of thousands of students in the capital of Seoul. And the southwestern province of Jeolla, an impoverished area where Kwangju is located, was a hotbed of radical dissent and opposition.

The U.S. and the South Korean regime were secretly preparing to crush the opposition, in Kwangju in particular. At the time, the U.S. had 40,000 troops in South Korea. Under a 1978 agreement, the U.S. and South Korean militaries operated through a joint command structure—the Combined Forces Command (CFC)—with the U.S. military commander (then John Wickham Jr.) in charge and had operational control of both militaries. A South Korean general was second in command, but had to request control of its main units from the U.S.2

Secret State Department cables, later declassified, revealed that the U.S. government “knew as far back as February 1980 that Chun was mobilizing special troops under U.S. command” to crush dissidents in Kwangju and that Gen. Wickham had given Chun control over these key military units. On May 8 and 9, U.S. Ambassador William Gleysteen told Chun and his forces that the “US government understood ‘the need to maintain law and order’ and ‘would not obstruct development of military contingency plans by reinforcing the police with the army’”.3

By early May 1980, there were daily demonstrations of tens of thousands of students in the capital of Seoul, demanding democratic rights and an end to martial law, May 20, 1980. (Photo: May 18th Democratic Movement)

May 18-21, The Murderous Assault on Kwangju Is Defeated

On May 17, 1980 martial law was extended throughout South Korea by the Chun regime. The aim was to suppress the massive and growing protests that had rocked the country for months.

Over the next two days, May 18-19, Chun’s “black berets” Special Forces were dispatched and began to massacre protesters who had barricaded themselves in the city of Kwangju for several days.

These paratroopers were set loose to raid homes, to beat, bayonet, shoot, torture, and murder protesters and even bystanders on the streets. They opened fire on civilians with M-16s and tanks. At least 17 cases of rape were confirmed, including of teenagers and a pregnant woman. There were reports of other atrocities—of disembowelments and of lynchings in the parks. Medical workers giving first aid were gunned down as well as children under ten.

Na Byung-un was working by day and taking classes for a university entrance exam by night. He recalled being “attacked by airborne troops while he was working on the second floor of the billiards hall. He was bashed repeatedly with a baton, and dragged to the ground floor, where soldiers tried to load him into a military truck...‘ Some people appeared and helped to pass me over a wall, where the troops couldn’t see me. Some women protected me. That is why I am now alive.’”4

Horrified and outraged by the military assault, the people of Kwangju fought back heroically and rose up in fierce resistance, forming citizen militias. Nearly a quarter of a million people, inspired and led by thousands of students, joined together and drove the elite troops sent to suppress them out of Kwangju by May 21.

Journalist Tim Shorrock, who reported extensively on Kwangju, paints a vivid description of the historic uprising:

With guns and weapons seized from local armories, a citizens’ army pushed the martial law forces out of town. As the Korean army threw a tight cordon around Gwangju, the people took it upon themselves to run their affairs. Virtually the entire city joined in, creating a self-governing community that many Koreans now compared to the Paris Commune of 1871. Women shared food and water with the fighters. Taxi and bus drivers shuttled rebels around the town and, on several occasions, used their vehicles as weapons against marauding soldiers. Nurses and doctors tended to the wounded. Citizens, young and old, flocked to local hospitals to donate blood.5

....hundreds of thousands of armed students, industrial workers, taxi drivers, students and citizens had gathered in a downtown plaza to celebrate the liberation of their city from two divisions of Army Special Forces troops who had been sent to quell anti-military protests ... It was the first armed insurrection in modern South Korean history.6

For five days from May 21 to May 27, anti-government masses controlled the city of Kwangju.

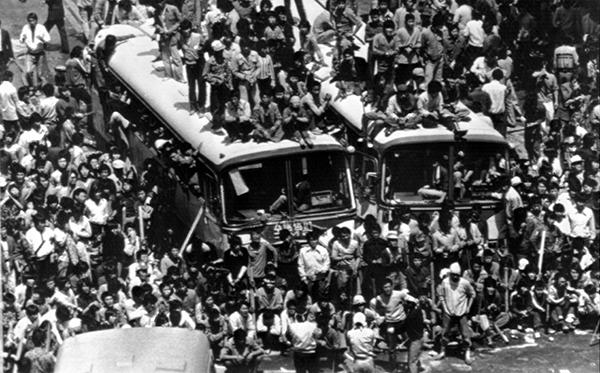

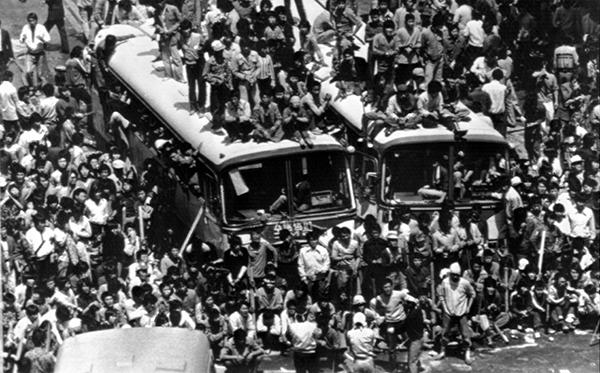

Horrified and outraged by the military assault, the people of Kwangju fought back heroically and rose up in fierce resistance, forming citizen militias and commandeering city buses to block city streets of Kwangju. (Photo: AP)

Jimmy Carter Plots to Crush Kwangju

U.S. officials were jolted by the mass takeover of Kwangju and the spread of anti-government uprisings to nearby cities. On May 22, Jimmy Carter convened a national security team meeting at the White House to decide how to crush the Kwangju uprising.7

Shorrock reports:

Within hours of the meeting, the U.S. commander in Korea gave formal approval to the Korean military to remove a division of Korean troops under the U.S.-Korean Joint Command and deploy them to Kwangju. The city and its surrounding towns had already been cut off from all communications by a tight military cordon. Military helicopters began flying over the city urging the Kwangju urban army—which had taken up positions in the provincial capital building in the middle of the city—to surrender. At one point, a Kwangju citizens’ council asked the US ambassador, William Gleysteen, to intervene [to] seek a negotiated truce; but the request was coldly rejected.8

The martial law commander in chief, Lee Hee Sung, later testified “that the date to send troops back into Kwangju was actually moved from May 24 to May 27 because of ‘the time needed for deploying the U.S. air force and navy from Okinawa and the Philippines in the near seas of Korea.’” Korean media reported that this redeployment of two U.S. aircraft carriers was also decided at the May 22 meeting cited above.9

At 4:00 a.m. on May 27, five divisions of South Korean paratroopers stormed into downtown Gwangju. They quickly overwhelmed the students and others who lay down in the streets to try and block their way, and after a 90 minute firefight, they defeated the armed citizen militias and seized control of Kwangju, arresting 1,740 protesters.

On May 27, paratroopers stormed into downtown Kwangju. They quickly overwhelmed the students, arresting 1,740. (Photo: AP)

ThoughtCo reports: “The Chun Doo-hwan government issued a report stating that 144 civilians, 22 troops, and four police officers had been killed in the Gwangju Uprising. Anyone who disputed their death toll could be arrested. However, census figures reveal that almost 2,000 citizens of Gwangju disappeared during this time period...[and] eyewitnesses tell of seeing hundreds of bodies dumped in several mass graves on the outskirts of the city.”10

The clearest U.S. endorsement of the South Korean General Chun Doo Hwan came in 1981. Then newly inaugurated President Reagan honored Chun as his first foreign head of state invited to the White House.11

President Reagan meets with Chun Doo Hwan.

THE CRIMINALS

President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) secretly gave the green light for the U.S. to back and facilitate the Kwangju massacre while publicly decrying Chun’s actions as part of attempting to put a “humanitarian” face on U.S. imperialism’s global crimes and exploitation.

Carter’s national security team that met on May 22 to develop the plans for a full out military assault on Kwangju: Secretary of State Edmund Muskie; Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher; top NSC intelligence official for Asian policy and former CIA station chief in Seoul Donald Gregg; CIA director Admiral Stansfield Turner; and U.S. Defense Secretary Harold Brown. The key players of this pack were the Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific Affairs Richard Holbrooke; and Carter’s NSC Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski who summed up the U.S. position on the attack of Kwangju “in the short term support, in the longer term pressure for political evolution.”12 They all agreed that the first order of business was restoration of law and order.

The U.S. military command of John Wickham Jr., David Jones and all those who were part of planning, leading and executing the assault on Kwangju and in the slaughter and torture of the Korean people, including aiming special cruelty against the youth and women.

Presidents Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) and George H.W. Bush (1989-1993) who continued to coverup the U.S. role and provide crucial military, financial and political support to the brutal South Korean regimes after the Kwangju massacre.

General Chun Doo Hwan, the South Korean Special Forces, other military units and police forces that directed and committed the Kwangju massacre in the interest/service of U.S. imperialism and South Korea’s ruling class.

THE ALIBI

The Chun regime claimed the rebellion was instigated by “communist sympathizers and rioters” while other rightwing forces in South Korea claimed the uprising was actually “led by 600 North Korean soldiers who infiltrated the city at the time.”13

Jimmy Carter and other officials publicly denied any U.S. knowledge or involvement in the Kwangju massacre. In 1989, the George H.W. Bush White House issued a white paper to reaffirm the story of U.S. non-involvement in the Kwangju massacre. Even when confronted with the discrepancy between the declassified documents and this white paper, State Department officials continued to insist the U.S. didn’t know what was going on and didn’t approve it.

Richard Holbrooke, hailed in the bourgeois press as an enlightened diplomat, later tried to justify the Kwangju massacre as the “tragic” outcome of “an explosively dangerous situation,” but one with the beneficial “long-term results for Korea” of “democracy and economic stability.” He also denied any U.S. role in the carnage: “The idea that we would actively conspire with the Korean generals in a massacre of students is, frankly, bizarre; it’s obscene and counter to every political value we articulated.”14

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE

There was never any evidence that North Korea had moved any troops, much less a large contingent of 600 soldiers, into Kwangju or anywhere else in South Korea before, during or after the uprising in Kwangju as right wing forces in South Korean had claimed.15

In reality, Carter’s and subsequent U.S. administrations had backed the Kwangju massacre to maintain its control of South Korea, which had been a bulwark of American imperialist dominance in the Asian-Pacific region and a forward base against “communist encroachment” in general, and against the Soviet Union and revolutionary China16 in particular, ever since the U.S. took control of South Korea after defeating the Japanese imperialists in World War II. From 1950-1953, the U.S. waged a savage war on Korea, killing three million Koreans and Chinese volunteers to maintain that control. (See American Crime #93: “U.S. Invasion of Korea—1950,” revcom.us, June 13, 2016)

South Korea served as a key military staging area for the U.S. during its war against Vietnam, and it remains a crucial base area in that region for the imperialists down to today.

In 1979 and 1980, the U.S. faced increasing challenges on the global stage. Richard Holbrooke bluntly stated one concern driving U.S. actions in South Korea in 1980 was “...nobody wants ‘another Iran.”’17

He was referring to the 1979 Iranian revolution which had driven the Shah (King) from power. America’s rulers were stunned because the Shah’s brutal regime was a key pillar of U.S. imperialist dominance in the Middle East, and one they considered “an island of stability,” as Carter put it in December 1977, literally weeks before the first protests that grew into the tidal wave that swept the Shah from Iran. When tens of thousands rose up and took over Kwangju, the Carter team feared it was facing another uprising which could threaten another client regime which had appeared to be stable.

The 1979 Soviet imperialist invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the intensifying U.S.-Soviet global rivalry also heightened the necessity the U.S. rulers felt to maintain control of South Korea.

1. William Blum, Rogue State: A Guide to the World's Only Superpower, pg. 150-151. Common Courage Press 2006. [back]

2. The armed forces of South Korea (or ROK) had a structure unifying the U.S. and the ROK leadership called the Combined Forces Command (CFC). The CFC’s top commander is a U.S. 4-star general with a ROK 4-star army general as deputy commander who had to request control of the units from the U.S. commander. The U.S. also had nearly 40,000 stationed at the border between South and North Korea. Chun was an army general who had received military training in the U.S., having specialized in guerrilla tactics and psychological warfare. [back]

3. Tim Shorrock, “Debacle In Kwangju”, The Nation, 1996 [back]

4. Kristen Alice, “May 18, An eyewitness account of the Gwangju Massacre”, The Korean Observer, May 19, 2015 [back]

5. Tim Shorrock, “The Gwangju Uprising and American Hypocrisy: One Reporter's Quest for Truth and Justice in Korea”, The Nation, June 5, 2015. [back]

6. Tim Shorrock, “Kwangju Declassified: Holbrooke’s Legacy”, Money Doesn’t Talk, It Swears blog, May 31, 2010 [back]

7. Ibid. [back]

8. Ibid. [back]

9. Bill Mesler, “Korea and the US: Partners in Repression” Covert Action Quarterly, #56, Spring 1996 [back]

10. Kallie Szczepanski, “The Gwangju Massacre, 1980”, ThoughtCo., January 23, 2019 [back]

11. In 1996, Chun was sentenced to death for corruption and his role in the Kwangju Massacre. His sentence was commuted in 1998. [back]

12. Shorrock, (n 6) [back]

13. Shorrock, (n 6) [back]

14. Tim Shorrock, “Debacle In Kwangju”, The Nation, 1996 [back]

15. The DMZ which separates North and South Korea has been one of the most closely monitored stretches of land on the planet by U.S. electronics, such as by U-2 spy planes and by the National Security Agency surveillance system. [back]

16. The Soviet Union was a genuine socialist country from 1917 until the mid-1950s and China was also a revolutionary society between 1949 and 1976. After socialism was defeated and capitalism restored in both countries, South Korea remained an important outpost for the U.S. contention with these rising capitalist powers. [back]

17. Tim Shorrock, “Ex-Leaders Go on Trial in Seoul”, Journal of Commerce, February 27, 1996 [back]