The Voyage of Charles Darwin is a seven-part, 350-minute BBC television series from 1978. I feel it’s a must-see, and it’s an ambitious undertaking—a powerhouse production.1

The series encompasses Charles Darwin's university days in the late 1820s, his five years on the HMS Beagle from the early to mid-1830s to the 1859 publication of his book On the Origin of Species as well as his later years before his death in 1882. The biopic is based on Darwin's letters, diaries, and journals, especially The Voyage of the Beagle and The Autobiography of Charles Darwin.

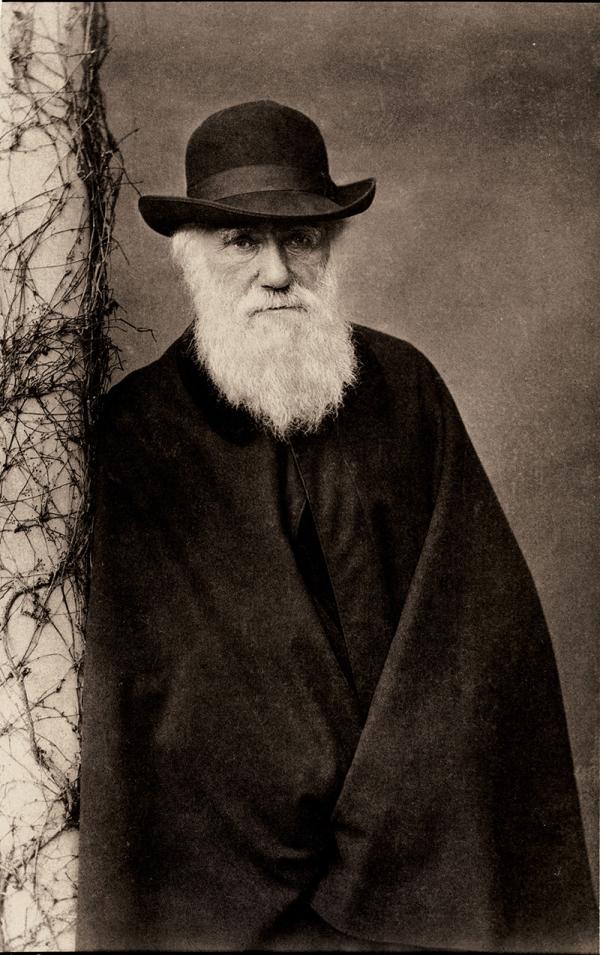

Charles Darwin, 31

Charles Darwin, 72 Photo: WikiCreative Commons

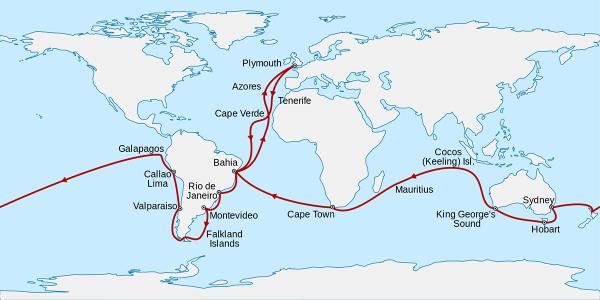

The heart of the series is the voyage Darwin took on the ship HMS Beagle from 1831-1836. On the HMS Beagle, Darwin crosses the equator and reaches South America. He’s at sea, where he develops friendships as well as important working relationships with some others on the HMS Beagle. Darwin develops an intense relationship with Robert Fitzroy, the captain of the Beagle. The ideological struggle between Darwin and Captain Fitzroy, an aristocrat and devout fundamentalist Christian, is especially riveting—it’s a struggle over how to interpret the world (including how to interpret new discoveries they are making on the voyage), a struggle over the scientific method vs. religious dogma. As you will learn, the struggle between them continues throughout their lives.2

Darwin spends much of his time on land, in fact Darwin spends more than three years of the voyage on land in South America. Darwin travels and meticulously collects plant and animal specimens of all types, fossils, fauna and flora, etc. He studies the Brazilian rainforest, spends time in Rio de Janeiro, then he’s on to the southernmost tip of South America in Tierra del Fuego, across Patagonia to Buenos Aires, and then to Valparaíso, Chile, and the Andes Mountains. One scene involves Darwin finding seashells 12,000 feet high in the Andes Mountains. He becomes convinced this proves the Andes Mountains were pushed up out of the sea over a very long period of time, and there is no way the story Genesis in the Christian Bible could be true. An explosive encounter between Fitzroy and Darwin occurs, as Darwin excitedly shares his seashell finding with Fitzroy, who takes it as a challenge to his faith in the Bible and an attempt by Darwin to undermine his biblical fundamentalism. We watch Darwin, a young naturalist with an open mind, searching for the truth—an emerging one-of-a-kind naturalist, geologist and biological scientist—combine incredible observational powers with a careful systematic approach as he collects all manner of natural life throughout the voyage. The series captures the breadth of Darwin’s insights and interests. Darwin brought back specimens of more than 1,500 different species, hundreds of which had never before been seen in Europe. He found fossils of extinct animals that were similar to modern species—including a giant species of mammal first discovered by Darwin in present-day Uruguay (whose skull was nearly the size of an elephant’s skull). The series also takes in Darwin’s developing theory of the formation of atolls, a type of coral reef.

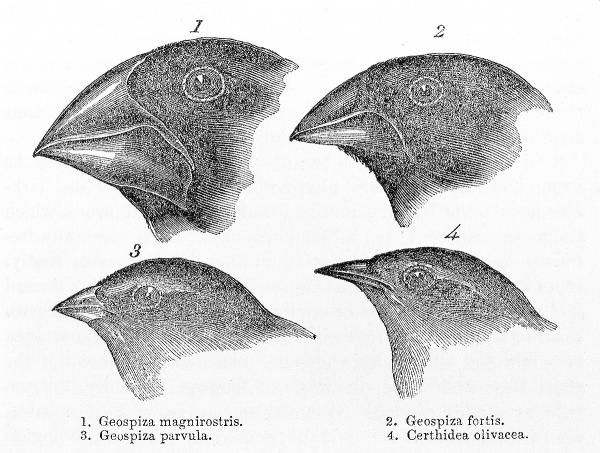

Charles Darwin journal sketch of four kinds of finch. Photo: Wikipedia

Toward the end of the voyage Darwin is on the Galápagos Islands, an archipelago (a group of islands) off the coast of Ecuador which straddles both sides of the equator. The series features the ecology, the endemic wildlife (species found only in one geographical location), and unique habitat of the Galápagos Islands. The once-in-a-lifetime five-week visit Darwin made to these islands had tremendous impact on his thinking about the natural world. This part of the The Voyage of Charles Darwin profoundly reveals the great influence the Galápagos would have on Darwin’s ideas on evolutionary theory.3

The culminating episode captures the backdrop of the 24-year period between Darwin’s return from the voyage and the publication of On The Origin of Species in 1859, including his hesitations on publishing his scientific breakthrough. This “backdrop” includes scenes of Darwin’s closest friends and scientific colleagues struggling with him to publish for the world his new theory of evolution.4

One of the reasons I am provoked to recommend this now is something I was particularly struck by—a scene toward the end. Darwin published On the Origin of Species in late 1859, and there is a tremendous uproar. The book is being burned and the Church of England is on the attack… even as you also get the sense Origin is “breaking through” in the context of the controversy and in the face of attack, reaching much wider circles of society than even Darwin and his proponents initially expected.

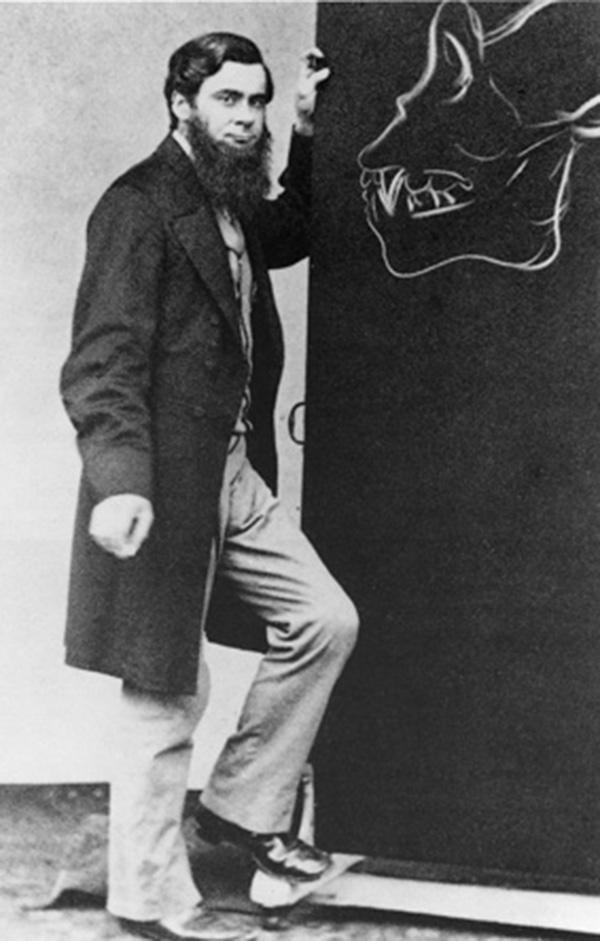

The stage is set for an historic debate, which in my opinion the series portrays excellently. It’s what is now known as “The 1860 Oxford Debate” (at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History) on Darwin’s new evolutionary theory, seven months after Origin was published. Several scientists and philosophers participate, but the dominant figures are, on the one side, Samuel Wilberforce, and on the other Thomas Henry Huxley. Wilberforce, a prominent clergyman, the Bishop of Oxford, was one of the great public speakers of his day—and arguing against Darwin’s theories. T.H. Huxley, a young comparative anatomist, argues for the Darwinian theory.

Thomas Huxley with sketch of gorilla skull, c 1870. Photo: WikiCreative Commons

Those who watch will no doubt be taken by any number of important themes and lessons of this debate, which has been called “one of the great stories of the history of science.”5 Here are two that stood out:

When replying to Bishop Wilberforce’s attack on Darwin and Darwin’s new evolutionary theory, T.H. Huxley makes this point, paraphrasing: “If, after 24 hours of tutelage in divinity, I were to stand here in front of this audience and make pronouncements upon the inadmissibility of the holy trinity, would you expect them to listen to me with care or consider me a charlatan…?”

Leaving aside the actual specifics, the non-existence of the holy trinity, there is an important underlying methodological point made here by Huxley that really resonated with me, of people just mouthing off on communism and revolution without any real study, scientific investigation or sifting through the evidence for the truth. In this context, I myself really learnt from, appreciated and highly recommend to readers Bob Avakian’s “An Open Letter to Theoretical Physicist Lee Smolin” in exemplifying a model approach to such needed struggle.6

Another lesson from The Voyage of Charles Darwin: The relish and certitude, the zest and spirit with which “Darwin’s Bulldog,” T.H. Huxley, along with Darwin’s best friend, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and a number of others, “went into battle” to fight for Darwin’s scientific breakthrough is inspiring and captured powerfully in the final scenes.

At the 1860 Oxford Debate, Bishop Wilberforce described Darwin’s new evolutionary theory as “…more than a theory… it is a direct challenge to Christian faith” and ridiculed Darwin for his “crude simplicity.” Wilberforce speaks to the audience and asks Huxley the now famous question: “Is it through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claims descent from a monkey?” You’ve got to see Huxley’s retort and be forewarned, Huxley had done deep work on Darwin’s new theory through studying Origin and had spent recent years, as he put it, “on the development of vertebrate anatomy and especially its relation to the origin of mankind” (on the transition from ape to humans).

This is a mind blowing and fun adventure of scientific discovery—take the time to check it out!

The Science of Evolution

and the Myth of Creationism

Knowing What's Real and Why It Matters

by Ardea Skybreak

Order from Insight Press