New Yorker writer Doreen St. Félix’s criticism of the Democratic National Convention (DNC) and her review of an important installation of flag art at the Paula Cooper Gallery in Chelsea (“Flag Waving and Flag Burning in Kamala Harris’s America,” October 5, 2024) is a sorely needed breath of fresh air, calling out the flag waving patriotism of the Kamala Harris campaign, the DNC and the artists who are willingly giving the “imprimatur of the civilized, the art-makers” to endorse and enhance the reputation of the Harris campaign and the country.

Speaking of the artists, especially Black artists, who are promoting unabashed love of country, St. Félix writes:

“Love of country” as Frederick Douglass analyzed, is a difficult essence to stir in the heart of the Black American. This past year, there has been a surfeit of so-called recontextualized patriotism, brightened and Blacked up, made sexy, in regions of culture outside of politics. There is Beyoncé, who let the Harris campaign use her 2016 song “Freedom,” featuring Kendrick Lamar, as its anthem. “Freedom” is a cut-and-dry protest song, about breaking chains and conquering troubled water. (The Lamar verse—“Stole from me, lied to me, nation hypocrisy”—isn’t getting spotlighted at Harris’s rallies.) The iconography of Beyoncé’s most recent album, “Cowboy Carter,” is rife with straight Americana—bluejeans, big hair, the big flag that she holds while straddling a horse. But observers hoping to detect any exciting irony in Beyoncé’s invocation of the flag will come up empty.”

Almost a decade ago, not long before Colin Kaepernick started kneeling, Lamar was stepping on a cop car as the flag waved behind him, performing “Alright.” As the song’s lyrics go, “Lookin’ at the world like, ‘Where do we go?’ / Nigga, and we hate po-po / Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure, nigga.”

“What happened between then and now?” asks St. Félix. “I don’t know whether we get far enough analytically if we chalk up the change to a mass degradation of the soul or a collective selling out, although that’s happening, too. The iconography of this country is so ubiquitous as to be symbolically moot. It is too much symbol—of violence, of imperialism, of ingenuity, of segregation, of hope. It is the spiritual deadness that is conveyed, not the jingo pride, as the cooler kids take up the Stars and Stripes in 2024.”

In contrast to this current outbreak of flagophilia, St. Félix turns to the artists who have produced a history of flag art.

I would have said the flag-as-muse theme was retro for a show in 2024, had the campaign season gone differently. The questioning of the flag in the art world is a twentieth-century tradition. Newer works can feel iterative, paling in vitality, recombinant critiques. But now the show seemed relevant, not nostalgic. The works in “Flags” responded to war, assassination, economic collapse, police violence; the artists, no matter where they were born, were made by the country and vice versa.

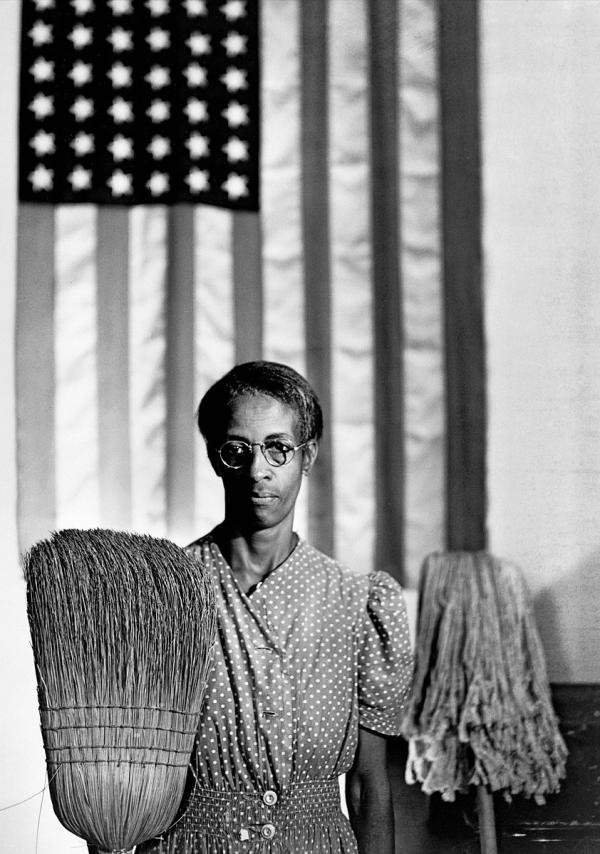

The show includes art from Jasper Johns and Diane Arbus to Gordon Parks's famous photo American Gothic and contemporary artist Dread Scott.

Cleaning Woman Ella Watson, (American Gothic) photographed by Gordon Parks for the Farm Security Administration. August 1942.

St. Félix further comments, “I’ve always thought of the Parks photograph, the subdued rage in it, as an antecedent for “What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?,” Dread Scott’s work displayed at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1989, which had visitors walk across a flag, laid on the ground, to testify to their experiences of marginalization on a ledger. The piece drew the ire of President George H. W. Bush; that same year, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling protecting the ‘desecration of the flag’ under the First Amendment. The artist helped change the flag and vice-versa. The piece is what you’re taught in school to disavow you of the idea that art is unimportant.”

For all those sickened by the ritual of embracing empire and singing praise to the number one oppressor on earth, there is the very simple question which contains words raised by the revolutionary leader Bob Avakian (BA): “When Was America Ever Great? Never!"

For everyone agonizing over the degradation of the soul and the collective selling out—BA takes it even deeper with a series of social media dispatches @BobAvakianOfficial addressing the need for A Profound Fight for the Soul of Black People: A Defeated People, Or A Revolutionary People? Radically and fundamentally breaking with the allegiance to this country is a major part of this fight.