by Juan Rojo

July 20, 2025

An Imperialist Parasitic Harvest: Savagely Exploitative and Entrenched, A contribution on the Historical Roots of the U.S. Domination of Mexico

by Juan Rojo

Downloadable PDFs:

** Printer Spreads

** Single Pages

From the editors:

We are proud to announce the publication in this issue of “An Imperialist Parasitic Harvest: Savagely Exploitative and Entrenched… A contribution on the Historical Roots of the U.S. Domination of Mexico,” by Juan Rojo. Rojo’s new-communist analysis of the U.S.-Mexico relationship would be welcome and important at any time. But coming today, when the fascist regime now running the U.S. insists on turning reality upside-down and scapegoating Mexico and especially Mexicans as parasites and criminals, Rojo’s work is a critically important and valuable reality check as to who are the real parasites and criminals. We urge you to read, study and spread this.

Personal introductory note from author:

I was born in East Los Angeles and grew up in South Central Los Angeles. My parents were both from Mexico, and my first language was Spanish. From an early age I was an inquisitive youngster and as I grew up I began to question why. Why were the people in our neighborhood treated so badly by the police? Why did my father work so hard and yet was not really treated with respect? It felt like people in our neighborhood were looked at as inferior, and people like me, Chicanos, were regarded with desprecio—like we were worthless. I hated this.

I dropped out of high school and at age 17 I joined the Army. I was stationed in France at the time when the people in Algeria were fighting for independence from France, and my eyes were peeled open by a close-up look at the horrific brutality of France’s colonization of Algeria. I also learned from the Black soldiers that it was not just in my neighborhood but in the whole country that Black people were viciously treated by the society and the police. That helped me see that there was something more systemic that explained what went on in my neighborhood in LA, although I still didn’t know the real story that lay hidden below the surface. When my time in the Army was up, I returned to life in LA, where I was unable to get regular work. The civil rights movement was impacting the whole country, and before long the protests against the Vietnam War were drawing thousands of people into the streets. The Watts rebellion in 1965—where our neighborhood was in the area that the national guard patrolled—signaled major changes in how people were standing up to that vicious oppression. Because I had been in the Army I was able to get money from the GI Bill to go to college. I was able to learn world history, explore philosophy, art history and cultural anthropology. I also was excited to learn about and participate in the Chicano student movement where we were able to talk openly about the vicious oppression that people of Mexican descent have suffered in this country and feel proud to be standing up against that. And this was at a time when all over the world people were standing up for their rights and for liberation. It was a very exciting time. But I was still the person who kept asking why. I still had that restless search to understand what was at the root of all the problems—all the injustice—to reveal what was hidden beneath the surface and discover what could be done to end it. I wanted the truth, not superficial explanations. I loved being part of the Chicano movement. But I began to see that the goals of that movement fell far short of the kind of radical solution that I felt was needed. I wanted to be part of a movement that was going to end all oppression not just for Chicanos, but for everyone that was treated as “less than” in this country and in other parts of the world.

I will forever consider it the greatest fortune of my life that my revolutionary activism and restless search for the truth propelled me into contact with the Revolutionary Union (the organization that led to the formation of the Revolutionary Communist Party in 1975). Through this, particularly learning from the approach of Bob Avakian, who played a leading role in the Revolutionary Union and went on to develop the new synthesis of communism, I was introduced to a thoroughly scientific approach to understanding and fighting to change the world. This completely transformed and enriched the path my life was on. Since that time, by taking up more and more consciously the leadership and method forged by Bob Avakian, I have only deepened my determination to contribute all I can to making the kind of emancipating revolution that I have learned is possible. A revolution that finally puts an end to exploitation and oppression in every form, not just here but all over the world. It is my hope that by applying this scientific method of dialectical and historical materialism to the important topics and history covered in this paper that I will inspire and pass a baton to younger people of today to take up this same science, this leadership, this method and to give all that you can in whatever way you can to this same emancipating mission.

* * * * *

Contents

Personal introductory note from author

An Imperialist Parasitic Harvest: Savagely Exploitative and Entrenched

1860s and 1870s

The Second Stage—El Porfiriato

The Impact of the Railroad

Impact of Regional Railroads on Capitalist Development in the West and Southwest of the U.S.

The Impact of Mexican Labor

Bibliography

An Imperialist Parasitic Harvest: Savagely Exploitative and Entrenched

There is a saying in Mexico: “Pobre Mexico, tan lejos de Dios, y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos,” that, translated, goes like this: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, and so close to the United States.”

As for the first part of that saying, no one is any further or closer to God than anyone else—for the simple reason that there is no god.1 The second part of that saying, however, hints strongly at the long and bitter history of United States’ plunder, exploitation and domination of its southern neighbor—even as not being on the U.S. border offers no protection from global U.S. aggression, from Vietnam to Iraq.

Much like a tree whose branches and leaves are visible, but whose roots are hidden, there are aspects of the U.S.’s domination of Mexico that are apparent and known, but whose historical roots are concealed, buried and less-known. My goal in this paper is to help uncover and expose an essential aspect of this, as a spark and inspiration to others, so we can all better understand the reality today—and what to do about it.

Many know about the U.S.-Mexican war in 1846-1848,2 in which the U.S. seized large amounts of territory, including the modern day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming, plus Texas which had already declared “independence”—a war in which U.S. generals who later became famous through the U.S. Civil War played a part. What remains hidden is the vicious exploitation of Mexico in the post-Civil War period, which ended up playing a crucial role—historically—in shaping the current reality of U.S. imperialism, the subjugation and impoverishment of Mexico, and the relations between the two countries.

The domination of Mexico played a pivotal role in building up the economic and military strength of the U.S. to emerge as an imperialist power in the 20th century. At the same time, this experience proved an early laboratory—and versatile and adaptable template—for the U.S.’s oppressive and exploitative dominance, which now stretches across the globe.

This relationship also played a crucial role in driving the capitalist development of the West and the Southwest, in how it developed, in the impact of regional railroads in “opening up the West and Southwest” to rapid agriculture, commerce and occupation of formerly Mexican and Native lands—the savage exploitation and bloody treatment, including the lynching of Mexican labor in this whole process.

Hundreds of Mexican laborers were lynched in the U.S. Southwest. Here, Francisco Arias and José Chamales, lynched on May 3, 1877. Photo: John Elijah Davis Baldwin

As a xenophobic white-supremacist fascist Trump/MAGA regime ratchets up its demonization and attacks on immigrants, accompanied by ludicrous claims that Mexico is “taking advantage” of the U.S., it is even more urgent and necessary to know and spread the truth of the real and untold history.

My intention in writing this paper is to build upon a lifetime of searching for answers, of learning, and to draw from important new scholarship, approaching and synthesizing all this with the scientific method of dialectical and historical materialism. This will help reveal and popularize the real-world causes for why the people of Mexico and their descendants within the borders of the U.S. today are in a subjugated position relative to the dominant powers of the U.S. And it will show how a factor in the U.S. building its wealth and racial identity and social cohesion was through its subjugation of its neighbor to the South, and how all this sits within the larger dynamics of the system of U.S. capitalism-imperialism. None of this was predetermined. It is not owing to any inferior or superior “human nature” of the peoples of one country versus the other. It is certainly not owing to the will of some nonexistent god or gods. But there are scientifically determined reasons.

Simply put, the dialectical materialist approach and understanding is that, as Bob Avakian, the revolutionary leader and architect of the new communism,3 has described, “there is nothing in the world, nothing that actually exists, or has ever existed or ever will exist, except matter in motion; that all existence, all reality, consists of matter in motion. Founded on and flowing from that, the basic principle of historical materialism is that the most fundamental human activity is the production and reproduction of the material requirements of life—food, clothing, and so on (and the reproduction of human beings themselves).”4

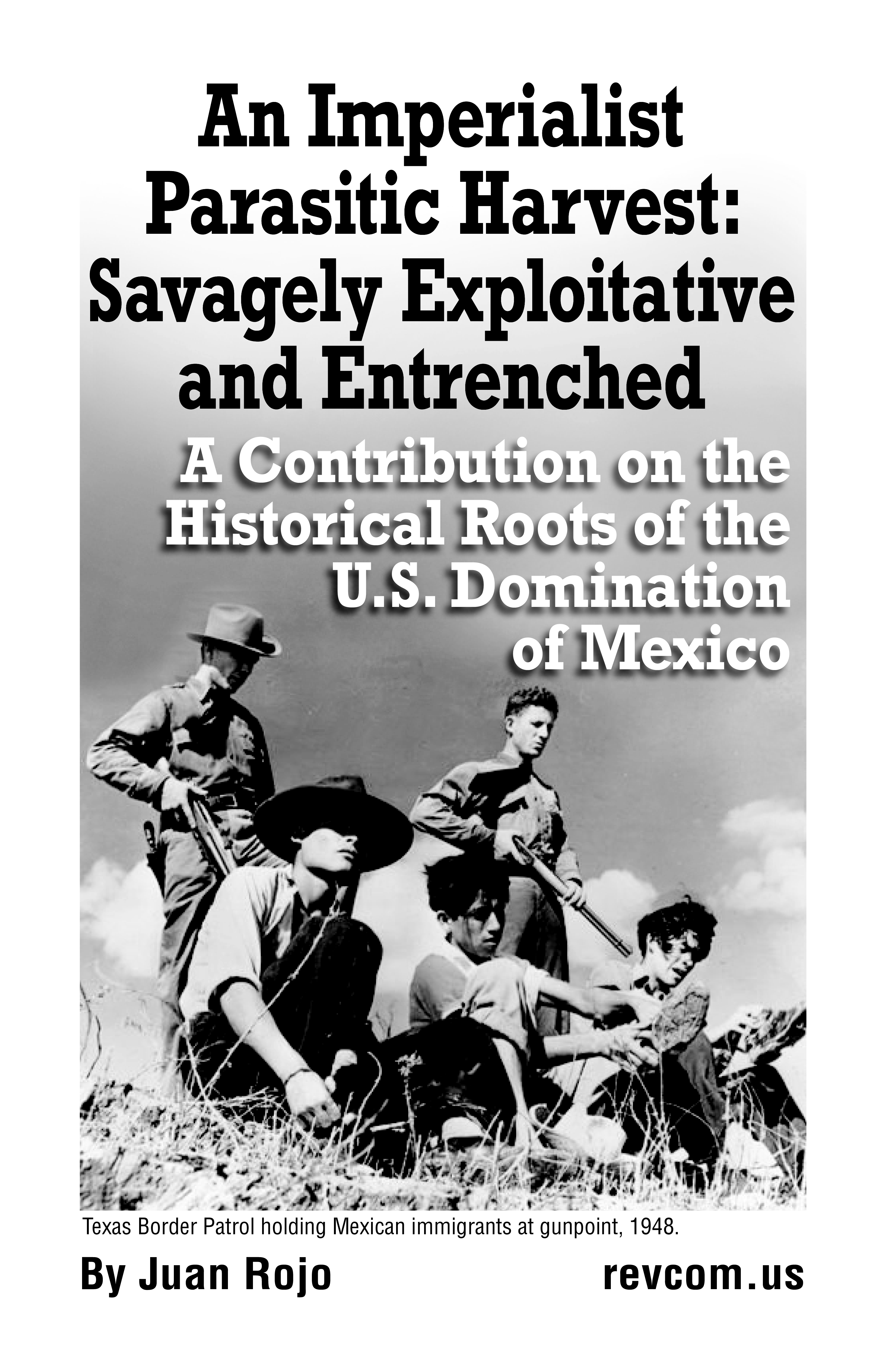

Texas Border Patrol holding Mexican immigrants at gunpoint, 1948. Photo: PD

By applying the evidence-based approach of dialectical and historical materialism to discover the underlying historical and real world reasons for why and how things developed as they did, I not only intend to shed light on how we got into the position we are in today and how this can be changed—I also hope to inspire and spur forward others to contribute to this exploration with regards to the U.S. domination of Mexico and to take up this same scientific method in tackling the multitudes of broader problems that oppressed people and humanity as a whole confront in understanding how we got in the situation we are in today and how we might change it in the real world towards ending all relations of domination and oppression everywhere.

* * *

That being said, there is a real and timely need to go into this history—between Mexico and America—in a way that has not been done before. In the introduction to his book Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War, John Mason Hart writes that his book is the complicated story of the Americans in Mexico as a precursor of world events. Americans entered Mexico well before they developed the capacity to exercise a powerful influence in the further reaches of the world. In that sense Mexico was a laboratory for U.S. economic and foreign policy.

A fair amount of what follows below is drawn from Hart’s book, from whose research and scholarship I have learned a lot. Some below are direct quotes, others paraphrased, and any omissions of direct attributions are entirely mine and do not reflect on my overall gratitude for and appreciation of this important work.

At the end of the U.S. Civil War, as an expanding American population began to move west in search of land and opportunity, the Mexican government was engaged in a struggle to expel the occupation forces of Napoleon III of France. Earlier in the century, Napoleon Bonaparte of France, in order to raise funds for an anticipated war with Britain, had sold Louisiana to the U.S. in 1803. The French were then expelled from Haiti with the victory of the Haitian revolution in 1804.5 With the U.S. engaged in the Civil War, the time was ripe and advantageous for France's move to attempt to establish its presence in Mexico. French troops began the occupation of parts of Mexico in 1861, and declared Maximilian I as emperor with hopes of establishing an overseas empire that would not only provide markets and raw materials, but would also check the expansion of the United States. Maximilian I was an Austrian archduke who became emperor of Mexico in 1864 following a bogus referendum, until his execution by the Mexican Republic in 1867.

The government of Benito Juarez (Mexican president from 1858 to 1872, leading the government and armed forces through the transition to the Mexican Republic) was resisting French aggression with widespread guerrilla war, and looked north for help. They realized that the Union victory in the U.S. Civil War offered Mexico a chance to procure weapons and munitions from the U.S. At the same time the U.S. was looking south, with a growing interest in Mexico by American elites. This was the historical context for the post-Civil War period profoundly shaping the relations between the two countries.

The Juarez government began its efforts by selling Mexican bonds to American investors. Mexican agents carried out their efforts in cities all around the U.S., with the blessing of the U.S. government. The bonds were sold at a great discount, and they were backed by land in Mexico. The Mexicans thus had the help of some of the most powerful and influential bankers and businessmen in the U.S. in the promotion of these very highly discounted bonds. The purchase of these bonds, which helped Mexico procure arms and munitions to fight the French, marked the first stages of American involvement in Mexico (after the Mexican-American war). Eventually the Mexicans were able to defeat the French.

The dream of a French empire extending from Europe to Mexico was smashed. Not so for the colossus to the north, as the U.S. is sometimes referred to in Mexico. For the United States the defeat of the French was an opening. The focus on Mexico that followed was of key importance, as it allowed the U.S. to establish control of the Mexican economy.

As I was becoming a revolutionary, continuing to search out root causes of the horrors in the world, I was deeply struck by a point made by Lenin, the great Russian revolutionary leader and theorist—that imperialist wars are not mere choices of “policy,” or the expression of any particular malice, but are driven and dictated by the need to expand and dominate. This involves competition among imperialist powers for resources, markets and control of strategically important areas like oil-rich regions or trade routes, which underlies and leads to conflicts and wars. As a theorist and author of the ground-breaking classic Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism,6 he states in his work, “To the numerous 'old' motives of colonial policy, finance capital [Ed: characteristic of imperialism] has added the struggle for the sources of raw materials, for the export of capital, for spheres of influence, i.e., for spheres for profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits and so on, economic territory in general. ….when the whole world had been divided up, there was inevitably ushered in the era of monopoly possession of colonies and, consequently, of particularly intense struggle for the division and the re-division of the world. … Monopolies, oligarchy, the striving for domination and not for freedom, the exploitation of an increasing number of small or weak nations by a handful of the richest or most powerful nations—all these have given birth to those distinctive characteristics of imperialism which compel us to define it as parasitic or decaying capitalism.” For those who want to explore, learn and scientifically understand more about this, I strongly suggest REVOLUTION #42, a social media message from Bob Avakian, titled Imperialism—and Imperialist War: What is, and is not, its fundamental motivation, nature and role, and how it can be finally ended.

With this understanding of the process of the development of imperialism, I have been able to explore the truth about the actual process of the history of U.S. involvement in Mexico. And I have learned how that has contributed to the U.S. capitalist class expansion and rise as a contending imperialist power.

1860s and 1870s

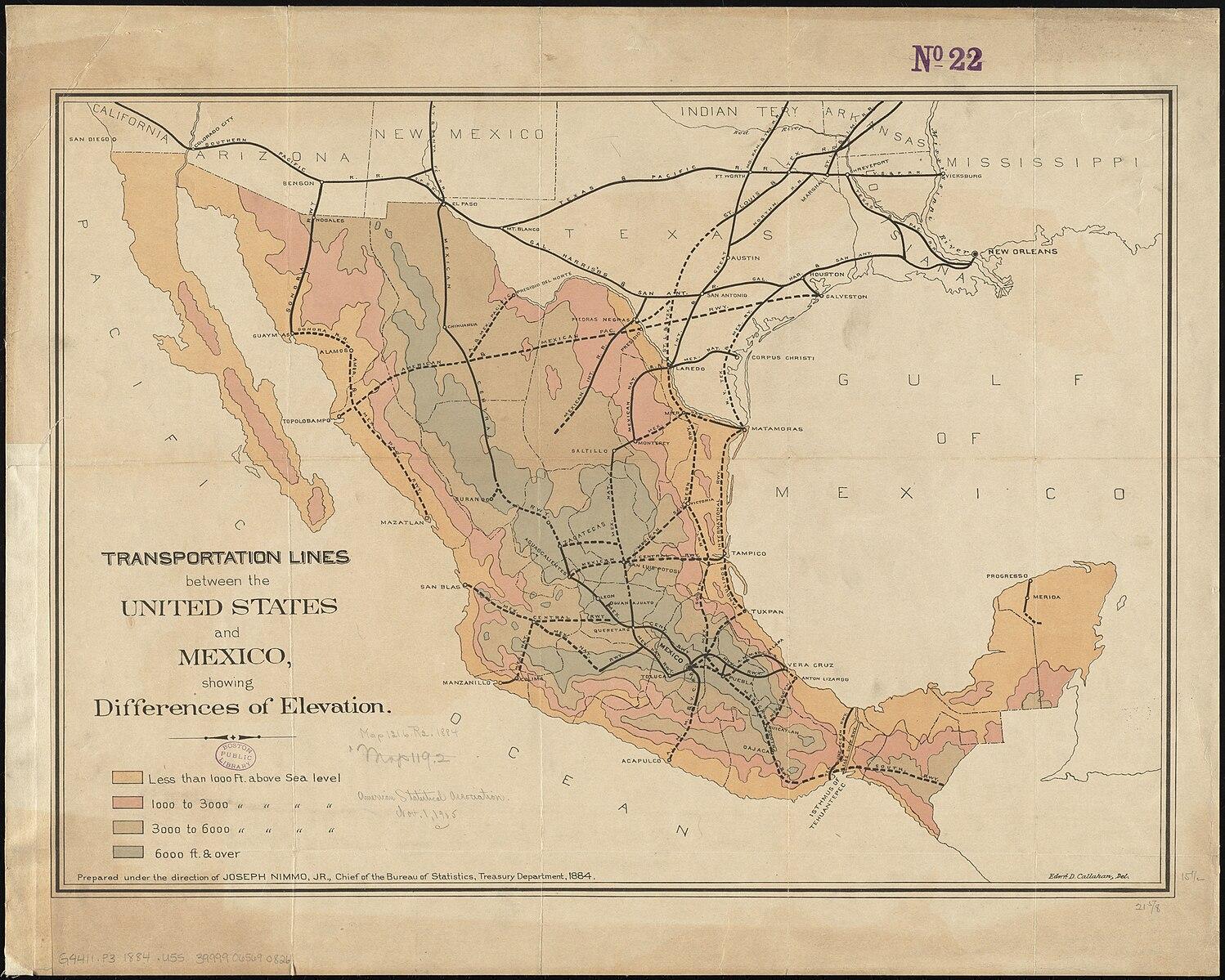

An important new stage of U.S. penetration into Mexico emerged with the development of new railroads in Mexico (circa 1900).

At the end of the U.S. Civil War the capitalists in the U.S. were able to put their attention to expansion to the West and Southwest territories, much of which the U.S. had stolen from Mexico. But they also set their sights on penetration into the territory of Mexico with energetic fervor. In order to establish their ability to control and dominate the economy of Mexico to the fullest extent possible, they set about building up the infrastructure for that. Hart writes, “The leading American capitalists recognized that the establishment of a railway system was the first step towards a modern multidimensional infrastructure in Mexico.”7 This required the cooperation of the Mexican government to a certain extent, but that “cooperation” also was established as an unequal relationship of domination of the U.S. capitalists over the Mexican government. The process of competition amongst the different U.S. capitalist groupings was a driving catalyst of the transformation of the Mexican landscape, ultimately integrating different sectors of U.S. capitalists into a network of domination and plunder.

Along with the railroads, Hart writes, “The complexity of the developing American presence in Mexico during the late 1860s and 1870s included important entrepreneurs and enterprises that were separate, even geographically removed, from the railroad machine that would soon envelop the country.”8 The period that followed the development of the railroad network saw the massive transfer of wealth and control, coupled with the dispossession of millions of Mexican people from their land, and the integration of Mexican regional markets into the United States through the railroads.

The Second Stage—El Porfiriato

Porfirio Diaz became president in 1876 and with a few interruptions ruled Mexico for about 30 years, establishing the period known as El Porfiriato. His approach to the role of the U.S. in Mexico further opened up the dominating position of the major capitalist captains in the U.S.

In 1883, a group of the most prominent capitalists and politicians of the United States gathered with their Mexican counterparts in the banquet hall of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City, signaling that a major leap in the penetration of U.S. capitalism into the Mexican economy was taking shape.

Collis P. Huntington, one of the leading American railroad industrialists and financiers of his time, chaired the meeting. Mexican officials presented the case for pervasive American participation in the development of their economy, and the American investors bargained for access to Mexico's abundant natural resources. The program of free trade, foreign investment and privatization of the Mexican countryside that they agreed upon that evening has influenced the relationship between the people and governments of the United States and Mexico to this day. And it was the Americans' next step in a progression that has expanded into and influenced the relations between the United States and the nations of the Third World in the 21st century.

American financiers entered Mexico well before they developed the capacity to exercise a powerful influence in the farther reaches of the world. But the most powerful among them already had a vision of world leadership. As Karl Marx, the founder of communism with Frederick Engels, famously stated: “Capital comes into the world, dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

The capital invested in Mexico by the U.S. came dripping with the genocide-produced blood of the Native Americans whose land became the United States, as they were dispossessed; with the blood of Black slaves, whose hundreds of years of enslavement was a major source of America's original wealth, and with the blood of the U.S. working class.

And that capital left Mexico dripping with the blood of the Mexican people, while the profits made and lessons learned served the U.S. in its future rise as a world power.

The Impact of the Railroad

Some may know about the U.S. transcontinental railroad,9 but what is hidden and less known is the impact of peripheral railroads in the U.S. domination of Mexico.

In the early 1900s the main form of transportation of goods in Mexico was the mule cart. Shown here 1912. Photo: LOC

Under the presidency of Porfirio Diaz, an important new stage of U.S. penetration into Mexico emerged with the development of new railroads in Mexico. In 1880, Mexico had fewer than 400 miles of railroad track. Most commerce still traveled by mule or by wagon over bumpy roads. Diaz knew that Mexico would never be able to participate in the world economy as long as the main form of transportation of its goods was the ox cart.

Thus the U.S. development of railroads in Mexico was a major investment, welcomed by Diaz. But those railroads were designed to run south to north, into the U.S.—to link Mexico's resource-rich regions directly to major economic hubs north of the border. Americans had little or no intention of developing internal markets, sharing technical expertise, or reinvesting in Mexican social development.

The Mexican Central Railroad was headed up by the Rockefeller-Stillman clan. The Mexican Southern line was run by E.H. Harriman and the Southern Pacific conglomerate. And 80 percent of Mexico's railroad stocks and bonds were controlled by other major U.S. investors, including Russell Sage, J. P. Morgan, the Guggenheim family, Grenville Dodge, Collis P Huntington, and Henry Clay Pierce. As a result, by l9l0, 77 percent of Mexico's mineral exports were shipped directly to U.S. markets. At the same time, those same railroads charged 50 percent more for goods shipped within Mexico than they charged for goods shipped across the northern border to the U.S., retarding the internal economic development of Mexico itself.

The patterns of investment led to enormous amounts of wealth transfer. To give a sense of the scale and scope: between 1900 and 1910, U.S.-owned mines in Mexico paid investors $95 million in dividends—an amount that surpassed by 24 percent the combined net earnings of all the U.S. banks based solely in the United States over the same period. Standard Oil's Mexican subsidiaries paid yearly dividends amounting to 600 percent of its investment annually. Companies that negotiated oil concessions during the Porfiriato paid a mere 10 percent tax on their earnings—an unheard of arrangement in the rest of the oil producing world.

The export of wealth through its extraction and repatriation to the United States—as opposed to Mexico’s local development, more equitable distribution through sustainable wages and tax redistribution, and reinvestment—meant that local economies were disrupted and destroyed in foreign investment-heavy regions of Mexico. And access to land or sustainable employment declined in relation to the existing population.

The value of Mexico's exports not only enriched a few investors and speculators in Mexico, it also benefited U.S. consumers and stimulated economic development in the U.S. By 1918, total Mexican exports amounted to $183.6 million, of which $l75 million was destined for U.S. markets. The profits made, and the lessons learned by the U.S., were the beginning stages in its rise as world power.

To encourage investment, the Mexican congress had passed the 1883 Land Reform Law, which entitled survey companies to one-third of any untitled lands they located and surveyed. The remaining two-thirds could be purchased at auction. And in 1893 Porfirio Diaz lifted the caps on the total amount of land any single survey company could acquire.

Investors rushed in, fueling a land grab that remade Mexico. Millions of Mexicans, including 98 percent of Mexico's rural families and communities, were left landless. In her book Bad Mexicans, Kelly Lytle Hernandez points out that using this law, William Randolph Hearst's father acquired 7.5 million acres of land and numerous mines. From Mexico, he extended his mine holdings into Latin America and around the world, but no other concentration of land or mining profits matched the family’s holdings in Mexico. William Randolph Hearst inherited his father’s holdings and used them to build a U.S. media empire. At one point Hearst was reported to have said, “I don’t know why we can’t just run Mexico to suit ourselves.”

This attitude of superiority and entitlement was not unique to this American capitalist alone. There was a whole ideological component that both rallied and justified taking over and exploiting the land and the people of Mexico. In Empire and Revolution, Hart describes this: “An American ideology necessary to support the Mexican project, but ultimately more far-reaching and enduring, had emerged. The expansionist attitudes toward Mexico expressed by the remarkably military post-Civil War political leadership of the United States reflected the increasing assertiveness of the American people. Their attitude was encouraged by their victory in that great struggle, their gains against the ‘savages’ on the frontier, and the effects of rapid economic and technological developments…. Assertions that Mexicans were ‘barbarians,’ and ‘semi-savage,’ that ‘they couldn’t rule themselves,’ and that their government had to be ‘taken in hand’ not only gained acceptance, but validated American ambitions.”10

Similar to Hearst and others’ acquisitions, the Guggenheim family took a controlling interest in ASARCO—American Smelting and Refining Company—leveraging the profits from their Mexican mines and smelters to do so. They soon controlled the largest system of mines and smelters in North America. John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and Edward Doheny's Pan American Oil and Transport Company, dominated Mexico's petroleum industry.

Doheny, a Los Angeles resident, controlled 85 percent of oil production after a gusher in Tampico, Mexico, made him one of the richest men in the world. Almost every penny of Doheny's fortune was extracted from Mexico. Cattle ranching, cotton raising, and timber were other industries with major U.S. investments and investors. J. P. Morgan, one of the leading U.S. bankers, owned 3.5 million acres in Baja California and controlled concessions of up to an additional 17.5 million acres across Mexico. The lead investor in Los Corralitos, an 893,650-acre cattle ranch in northwestern Chihuahua, a size a third larger than Rhode Island, was American. The Richardson Construction Company based in Los Angeles snatched up 993,650 acres of timberlands in Sonora, Mexico. And Republican Senator William Langer of North Dakota owned 750,000 acres in Durango and Sinaloa.

Impact of Regional Railroads on Capitalist Development in the West and Southwest of the U.S.

The major railroad lines through the Mexican interior to the U.S. border were owned and controlled by U.S. businesses. Image: U.S. Department of Treasury

The economic development of the West and the Southwest coincided with the northward drift of Mexico’s population. Regional railroads such as the Southern Pacific, the A.T.S.F. (Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway), using Mexican and other immigrant labor, integrated the southwest of the U.S. into the overall development of the U.S. economy. Mining shifted from precious metals to industrial metals such as copper and coal as in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Oklahoma. Copper mines in the West increased from three in 1869 to 180 in 1909, and coal mining largely using Mexican labor boomed in these states. Citrus and cotton cultivation flourished because of rail facilities’ cheap labor and desert irrigation projects encouraged by the federal Newlands Act of 1902.

The population of Texas nearly doubled between 1880 and 1900, reaching three million. Ronald Takaki, the author of A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America, pointed out that the railroad and the forces it represented—the expansion of white settlement and “civilization,” and the expanding market—made it clear that the Indian of the "past" had no place in technological America.

General Sherman, the Union general during the Civil War, stated that the railroads enabled them to send soldiers to threatened points at the rate of five hundred miles a day, thus overcoming in one day, a journey which used to require a full month of painful marching. He also said, “A vast domain equal to two-thirds of the whole United States has thus been made accessible to the settler.” Here the use of the railroad by the U.S. Army was a key factor in the military campaigns against the Native Americans, who resisted the white settlers taking their tribal lands. The railroad thus played a decisive role in the genocidal massacre of Native Americans then living on land the settlers wanted.

The railroads played a crucial and dynamic role in the settlement of the Great Plains and the Southwest, spurring mining, agriculture, ranching and trade—but also in terms of direct efforts by the railroads themselves to get settlers from Europe and from other states like Pennsylvania and New York. For example, as historically documented about the settlement of Kansas, the Wichita Eagle reports, “The railroads, trying to sell the millions of acres given to them by the U.S. government… promoted Kansas all over Europe and Russia and the rest of the American states. ‘The railroads were highly privileged, and the Supreme Court supported them lock, stock and barrel,’ said Robert Linder, history professor at Kansas State University.”11 Along with the Homestead Act, the expansion of the railroads drove and hastened settlement. “In Kansas, land offices recorded thousands of acres and entries. With the Santa Fe Railroad advancing through Larned, Kansas, starting in 1872, there was an explosive growth of settlement with its connection to the wider rail networks. In 1877 alone, the Larned land office parceled out 145,878 acres.”12

The land had been there waiting; for years anyone could have had it. But no settlers wanted it, because there was no way to make a living on it without cheap, certain, and reasonably speedy transportation. The market could not absorb the old freight charges, which had often been higher than the cost of the goods themselves. The railroad changed all this almost overnight.

Stagecoaches and freight wagons retreated and faded away as the track ran west. They simply could not compete. A train could travel at 20 miles an hour and could haul tons of freight, something not possible with either stagecoach or freight wagons. People could not exist as farmers along a stage line; they could prosper within a few miles of railroad track because of rapid transportation and distribution at scale.13

The impact of the railroad could be seen in the following from Traqueros.14 By 1879, ten years after the transcontinental railroad linked the East to the West, the rail linkage of the country totaled ninety-three thousand miles of operating line and had a value of $5.4 billion. And of course the railroad greatly facilitated the Americanization of the west and the southwest. When these new railroads arrived, the cost of transportation dropped low enough for operators to extract lower grades of ores profitably, crucial then to the rapidly industrializing U.S. The open cut mining method, first perfected at the Bingham Canyon mine in Utah just south of Salt Lake City, was one of the largest open pit copper mines in the world. Miners referred to it as “the richest hole on earth." As an illustration of the economic impact, the Guggenheim family first developed Bingham Canyon and passed it on to the Kennecott Copper Company in 1910. Four years later, Kennecott reported that the mine had produced upwards of $1 billion worth of copper.

The Impact of Mexican Labor

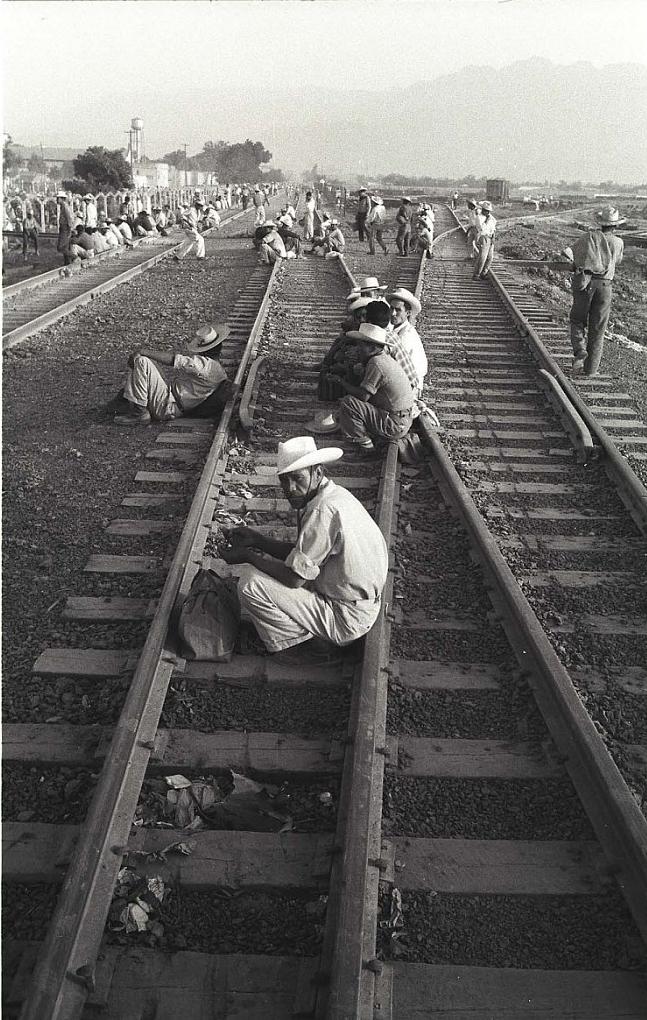

Traqueros (Mexican railroad workers): The peak of traquero employment programs in the U.S. was between 1880 and 1915. Photo: National Museum of American History

The proximity of the Western copper industry to Mexico made it necessary for American capitalists to woo Mexican mining interests to modernize in order to both access the extensive mineral resources of Northern Mexico and to recruit trained Mexican labor. Mexican workers and land provided the backbone for mining on both sides of the border. However, skilled occupations tended to be the domain of white workers imported from the East, while unskilled Mexican workers were imported from Mexico.

The economic development of the American Southwest coincided with, fueled and drove the northward drift of Mexico's population. This migration led an estimated one million people to move to the United States by 1920. By 1910, 12 million people in Mexico lived in rural areas where agriculture and mining were prominent activities, and an estimated 98 percent of this population was landless, according to Justin Chacon, the author of Radicals in the Barrio: Magonistas, Socialists, Wobblies and Communists in the Mexican-American Working Class.15 People migrated within Mexico seeking a way to feed themselves and their families. While agricultural exports rose 200 percent between 1876 and 1900, production for basic food stuffs declined every year, leading millions to cross the border, under pain of extinction.

In the book, Radicals in the Barrio, Chacon estimates that hundreds of thousands left home to find work elsewhere. Economic displacement coupled with the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920),16 inflation and higher prices, starvation, over-saturation of diminished labor markets, declining working conditions and violence led one million people to move to the United States by 1920.

By 1930, over 1.5 million Mexicans lived in the United States, with the great majority settling in California, Texas, Arizona and New Mexico. This sparked a mass population shift northward from within the heartland of Mexico that continued as U.S. capitalism became structurally dependent on Mexican labor for its capital accumulation, sustenance, and growth—a trend that continues to this day.17

Between 1900 and 1940, for instance, the total population of the U.S. states on the Mexico border increased from 6 million to 14.5 million, with most of the growth coming from Central and Southern Mexico. The depletion of the Mexican rural population coincides with the growth of the Mexican population in the United States and the expansion of capitalist production based on Mexican labor in the southwest of the U.S.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, Mexican immigrant workers far outnumbered all other groups of immigrant and native-born labor on the railroad tracks in the U.S. Southwest.

In the popular lore of the American West, the Chinese and the Irish built the railroads, laying track, digging tunnels, and building trestles and bridges. This picture is largely true for the transcontinental railroad completed in 1869, but not necessarily for the decades that followed. By the 1890s, the railroads slowly replaced Chinese track crews with Mexicans on the West Coast lines. By the turn of the century, Mexican immigrant labor far outnumbered all other groups of immigrant and native-born labor on the tracks in the Southwest. Racist attacks on the Chinese and Mexicans were common, including lynching, a little-known fact.18 All of this is part of the peculiarly American historical context for what we confront right now, including the overt resurgent white-supremacy and horrific demonization and targeting of immigrants in contemporary times by the fascist Trump regime.

* * * * *

What I have written is only the tip of the iceberg of the true story of this whole period of U.S. penetration and exploitation of Mexico and its people. I will have succeeded if you have learned some new things through reading this, if you have developed a deeper sense of the historical roots of the imperialist domination of Mexico by the U.S. I will have further succeeded if you have been inspired to make known, to excavate and study more of this history, and to apply and deepen this method of scientific historic analysis, as part of and in service of radically changing the world, of emancipating humanity.

We, the people of the world, can no longer afford to allow these imperialists to continue to dominate the world and determine the destiny of humanity. And it is a scientific fact that humanity does not have to live this way. —Bob Avakian

* * * * *

Bibliography

Anderson, Gary Clayton, The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land 1820-1875 (Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2005).

Baumgartner, Alice L., South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War (New York, Basic Books, 2020).

Chacon, Justin Akers, Radicals in the Barrio: Magonistas, Socialists, Wobblies, and Communists in the Mexican American Working Class (Chicago, Haymarket Books, 2018).

Garcilazo, Jeffrey Marcos, Traqueros: Mexican Railroad Workers in the United States 1870 to 1930 (Denton, TX, University of North Texas Press, 2012).

Hart, John Mason, Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, University of California Press, 2002)

Hernandez, Kelly Lytle, Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire and Revolution in the Borderlands (New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2022).

Marshall, James Leslie, Santa Fe: The Railroad that Built An Empire, (New York, Random House, 1945).

Jones, Reece, Nobody Is Protected: How the Border Patrol Became the Most Dangerous Police Force in the United States (Berkeley, CA, Counterpoint, 2022).

* * *

Additional Books Related to the Subject:

Behnken, Brian D., Borders of Violence & Justice: Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Law Enforcement in the Southwest, 1835-1935, (Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

Madley, Benjamin, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2017).

Martinez, Monica Munoz, The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2018).