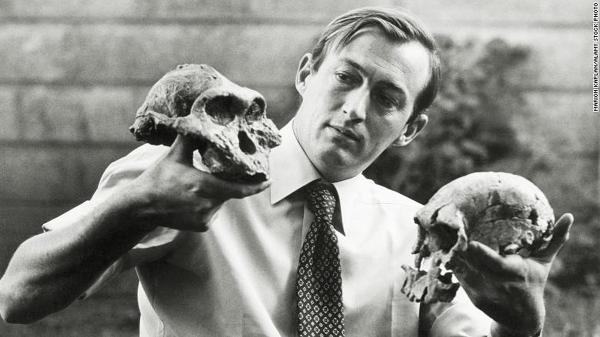

Richard Leakey, with the two fossilized skulls of two ancestors of humans discovered in 1977 near Lake Turkana, Kenya Photo: Alamy

Richard Leakey died at his home in Nairobi, Kenya, on January 2 at the age of 77. His death is a real loss for the people of the world, and it is important to understand what he accomplished and why it is significant.

Leakey, author of several books, including ORIGINS, and co-author of The Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Mankind, and widely known for his work as a wildlife conservationist in Kenya (which I will return to), was a paleoanthropologist. Anthropology, broadly defined, is the study of humans. Paleontology is the study of fossils. Paleoanthropology is the study of the early development of humans, including the evolutionary pathway that led to the emergence of the human race (scientifically named homo sapiens). You might characterize paleoanthropologists as “fossil hunters” but the fossils they are looking for are not dinosaurs’, but those of early humans and our ancestors. It is painstaking work, often in difficult conditions, with not only advances but setbacks and failures, as in most science, but at the same time precious to humanity.

The Leakey family name is one of the most famous in all of anthropology. Richard’s parents, Louis and Mary, were both ardent advocates of Darwin’s theories on evolution. Their fossil discoveries, including in the Olduvai River gorge in Tanzania and Mary Leakey’s later discovery of Homo habilis (the “tool maker”), an ancestor of modern humans, who lived around 2 million years ago, helped revolutionize our understanding of who we (humans) are as a species and where we originated as a species, with common ancestry—from the Rift Valley of Africa.

A Passionate Curiosity and Ferocity for the Truth

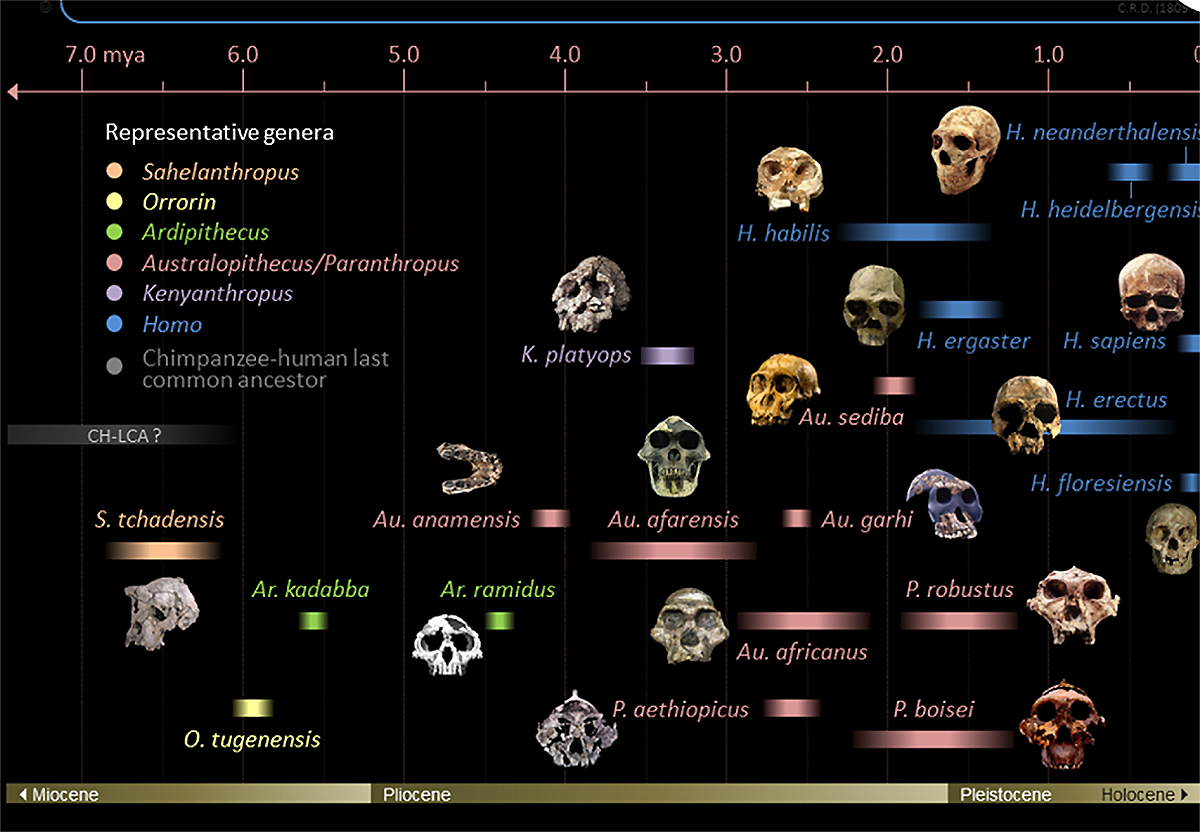

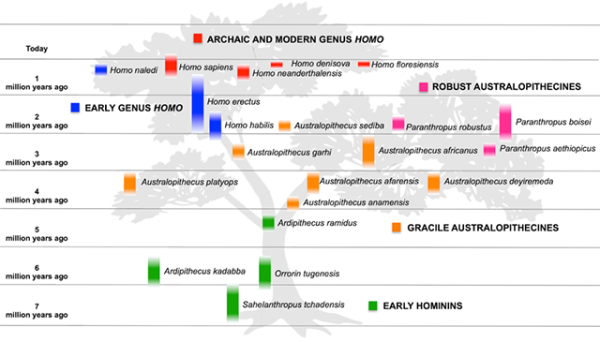

Richard Leakey grew up in this environment, unearthing his first fossil when he was four years old. Dropping out of high school, he began leading his own teams on “digs” in his early 20s. Over the course of his career, his teams, including his second wife, Meave, working primarily in the Turkana Lake region of Kenya, accumulated what is considered to be the most extensive and diverse collection of hominid1 fossil records in existence, helping to fill many gaps in our understanding of the evolution of the ancestors of humans (homo sapiens) and giving us a much clearer understanding of the evolutionary process.

Leakey understood that the fossils his team, and others, were excavating provided further irrefutable evidence of the validity of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution; that all living species (including humans) change over time due to adaptation to changes in their environment, and that some of these changes will lead to the emergence of entirely new species. This brought him into repeated clashes with religious fundamentalist fanatics, who couldn’t accept the scientific reality that not only were humans (scientifically named “homo sapiens”) related to apes but that we could technically be considered “apes” ourselves, because going back some 5 million years, fossilized remains had shown that humans and what are today known as the “great apes,” including chimpanzees, had a common ancestor. Leakey relished explaining to audiences and challenging religious fundamentalists with the fact that chimpanzees share over 95% of the same genes as humans.

He greatly appreciated and supported the work of others in this regard. After reading Ardea Skybreak’s The Science of Evolution and the Myth of Creationism,2 he wrote, in part, that the book was “…of tremendous benefit to many, especially those in the teaching profession where there are frequent opportunities to defend science against the ridiculous assertions by religious zealots and fundamentalists.”

As anthropologists continue to discover new fossil records, in different parts of the globe, our knowledge of the hominin family tree, stretching back almost 7 million years, including of homo sapiens, the only member of the hominin family still alive, continues to come into clearer focus.

Contributing to the Interests of Humanity

He was even more passionate about popularizing another aspect of human evolution—the proven fact that all human beings are one species (homo sapiens) and, irrespective of whether we are an indigenous tribe in the Amazon or New Guinea, African, Asian, Native American or white European, we are all descendants of a small group of early homo sapiens situated in sub-Saharan Africa, who migrated out of Africa to populate the rest of the planet. Leakey was here greatly aided by scientific advances in genetics that were able to confirm this by testing the genes of populations of humans from around the globe. Later genetic investigation confirmed that all of humanity can be traced to those early waves of migrations that started out of Africa some 125 thousand years ago.3

On the significance of this, Leakey once wrote, “I believe that if we can make the science of the origins of humanity accessible and exciting to everyone, and show people the amazing journey of humanity, we can shift paradigms and change the world.” At the time of his death, he was leading an initiative to build an international museum in Nairobi to celebrate this journey.

For Richard Leakey, the understanding that we are all one species, of a common ancestor, opened up amazing potential for humanity.

Leakey was also against “bad” or “junk” science used to justify oppression. Early anthropology had played a role in justifying the horrific and brutal European conquest of sub-Saharan Africa—that even those (Black) Africans, who had developed highly evolved societies, were of an inferior species to white Europeans. Leakey felt that the more people around the globe came to understand that Africa—particularly, sub-Saharan Africa—was the birthplace of all of humanity, the more unacceptable the continued exploitation and brutalization of the African people would be seen in the eyes of the rest of world.

In the late 1980s Leakey pivoted away from the day-to-day work of paleoanthropology and turned his attention and towards another lifelong passion, wildlife conservation. He is often credited with saving the African Elephant and African Black Rhinoceros from extinction. These were the early days of wildlife conservation and marked by wrong—and at times grievously harmful—approaches to the complex relationship between the people involved in poaching and greater forces at work.4 It is beyond the scope of this letter to dig into all of this. His later involvement in official Kenyan politics, his lifelong home, was also problematic.

However, this does not necessarily diminish Leakey’s scientific contributions and his commitment to making these contributions and those of other scientists more broadly known and accessible to broad masses of people. He was fearless in this regard, willing to risk friendships, professional advancement and even his personal safety,5 to fight for what he knew to be true or understood what is needed. There is much to be cherished in his example and he will be missed.