On August 29, 1970 over 25,000 Chicanos from across the country marched down Whittier Boulevard in the Boyle Heights District of Los Angeles to demand an end to the Vietnam war and an end to national oppression. The march was organized under the slogan “Raza sí, guerra no.” The demonstration was viciously attacked by the LAPD and Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department deputies, and three people gave their lives in the struggle that day as people heroically defended themselves against the police attack. On the 30th anniversary of the Moratorium, a group of revolutionary youth interviewed a veteran comrade (known now as Juan Rojo) who was in the middle of the Chicano Moratorium 30 years ago.

Question: Looking at the Moratorium through the eyes of a generation which has been politicized by things like the anti-immigrant Proposition 187 and the anti-affirmative action Proposition 209 and things like that—those are the issues that like this generation is confronting now—what was going on, what politicized your generation?

Juan Rojo: You have to step back for a minute and you have to look at what was happening in the world at that time. The Vietnamese people were showing the people of the world, all over the world, that a small country can defeat a big country—that if you have right on your side and if you are determined to be free, that you can actually inflict your will on the oppressor.

People's Army of North Vietnam, circa 1967. Archives of Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO), 1967

That was not lost on the people of the world. And it certainly was not lost on the Chicano people. And the Chicano Moratorium came toward the end of the anti-war movement, and the reason for that is that it was very controversial to oppose the war. Chicanos had been taught that it was a good thing for us to shed our blood for the United States. There were many Chicanos in the military. It took a while before people began to realize that dying for the imperialists was not in their interest—and to begin to organize to make that fact known to the world, that we were not going to die in their goddamn war.

But it was very controversial. And it took place, like I say, at a time when the Vietnamese were waging struggle against the U.S., and defeating them, sending the troops home in body bags. I remember seeing photographs of body bags waiting to be loaded on the planes. There were so many you couldn't even count them. Something had to change and the Chicano Moratorium was an expression of resistance and defiance to what was going on, and in part it was aided by the heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people and other struggles that were going on in the world.

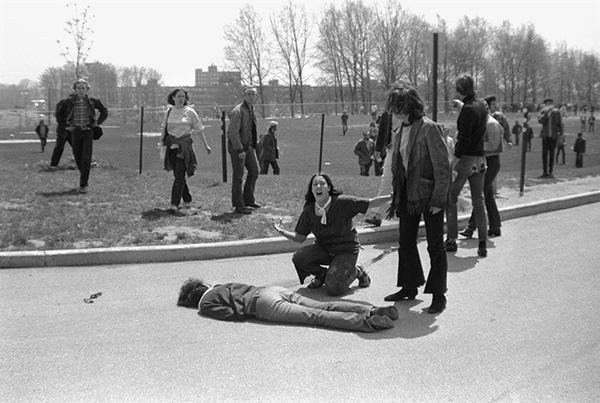

At Kent State University, the National Guard fired into a crowd of protesters, killing four and wounding nine. May 4, 1970,

Around this time, you had the National Guard shooting people down at Kent State and the pigs murdered people at Jackson State, a Black college which nobody hardly talks about. The U.S. had spilled the blood of college students both Black and white. And the other thing was, I think there was a yearning for Chicanos to come together in a political act. I think this is one of the very first times that Chicanos from all over the United States got together. I remember the day of the march seeing banners from Kansas City, from Minnesota, from Chicago, from all over the place. From all over the Southwest, too. And I think part of what the people wanted to do was come together to express outrage at the war in Vietnam, opposition to sending their children to die in it. And I think besides all that, there was some other things that were going on. You know if the war would have ended that minute, the problems that the Chicano people faced would not have ended, and the question of the war was only one issue.

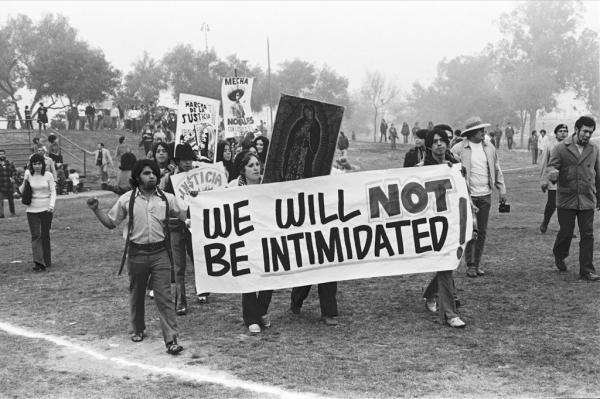

Protesters gathered from all over the country to participate in the events in East Los Angeles. Image courtesy of the UCLA Library Digital Collections, Creative Commons License

And so the things that politicized people were things like police killings, genocide, the war, the racism, you know, the drop-out rates in the schools, the destruction of language and culture, were all things that really bothered the Chicano people. And when they came together, that sort of pulled them together as a group. I think the main point was a question of the war. But I don't think that's the only reason why Chicanos came together that day.

This was not something that had ever happened before. This was the first time in history that you had this kind of a gathering. And I'm not just talking about the numbers. The numbers were like 25,000 to 30,000. That's very significant. The makeup of the crowd was a lot of students, and a lot of proletarians and people from all over who had never had contact with each other before. This was not some kind of annual event, it had never happened before. And again, to get to your question about what politicized people—it was all of that, it was the war and just the way you had to live every day in this country. And it was the inspiration of other people standing up and fighting for their rights, all together, that politicized people.

What we did in the course of that, the Revolutionary Union—the Party did not exist at that point—the RU organized a Chicano contingent within the Moratorium. We raised slogans and chants and stuff like that which we thought were important to reflect the actual conditions of the Chicano people and to begin to point the way forward out of all this mess. I was just reading from the RU's Chicano pamphlet and I'll quote:

"In August of 1970 over 25,000 Chicanos from across the country gathered in Los Angeles to demand an end to the Vietnam war and an end to national oppression. The march was organized under the slogan, 'Raza si, guerra no.' Some of the demonstrators brought out even more advanced consciousness, that some wars such as those for national liberation are just, while the wars for imperialist aggression are unjust, and through such slogans as 'Victory to the N.L.F., raza si, guerra aqui."

Everybody that was in the march didn't agree with this. Some of the people who organized it were horrified that we would talk about victory to the Vietnamese people, but we thought that was an important point because theirs was a just struggle as well. And anything that we can do against U.S. imperialism can only strengthen the fight of other people being oppressed by U.S. imperialism. So we chanted those chants, and those chants were taken up by the people. It made a lot of sense.

The other point was “guerra aqui.” That's the point. We didn't think that the only problem that Chicanos faced was the conflict in Vietnam—a long ways from here. But it was a conflict in the streets of the United States and the Chicano communities, wherever Chicanos found themselves. They were facing national oppression, and that had to be brought out. And we did our best to do that. And again, it was welcomed by the masses. It made people stop and think.

Why wouldn't we say we only want peace? I remember somebody said, "Why don't you want an end to the conflict?" And we told people because the thing that caused the conflict hasn't ended. We think the Vietnamese should defeat the United States. Some people said that's treason. You want the defeat of the United States?! And we said, you goddamn right we do.

Q: So this was controversial?

A: This was a new thing to put forward to people. Nobody else was talking about working for the defeat of U.S. imperialism. Some people saw it like—as long as it doesn't affect our people, if we don't die in the war, that's okay. And some of the people said, well, that's not the way to look at it. The way to look at it is the United States should get its ass kicked. It should be weakened as a result of this battle, not strengthened. And a lot of people, when they thought about it, said, well you know, that makes sense. Which I think was the most common response.

But the main thing I want to raise is that it was controversial, and people stopped and thought about it. They went like yeah. And some people didn't agree with it, and some people did, and a lot of people stopped to think about it and hadn't made up their minds yet. But again all this was happening in the context of a small country kicking the ass of the United States. And that was unprecedented. They got their ass kicked in Korea, but they always called that a "police action." They were getting their ass kicked again and they didn't like it and we celebrated and we thought it was a great thing.

Q: I was wondering whose idea was it to have this huge march. Was it different organizations? Or was it one organization? Who was the one who thought of this whole march in L.A.?

A: Here's what I know about it. I was involved in one of the Moratorium organizing committees. There were different ideas on the matter. There was agreement around joining the struggle against the war in Vietnam. We all agreed that it should be organized and we should have a series of demonstrations culminating with a big demonstration in Los Angeles. There were a lot of small moratoriums. There was one in Oakland and, I don't remember all the cities, also in quite a few cities, including cities in the Midwest. Which is why those people came.

We learned a lot from the big anti-war movement. Just before the Chicano Moratorium, there had been anti-war demonstrations of 500,000 people on the East Coast and 250,000 people in San Francisco. These were huge things. So people began to sum up the experience of that anti-war movement. And what they had done, how they started out small. You don't start out with 250,000 people in San Francisco. The first ones were relatively small, so people drew some lessons from that.

In those days, you could go live in people's homes—we relied on the people. If we had to send somebody somewhere, they went and stayed in somebody's house and ate what people could give 'em. So we didn't have to have a lot of money. And again, I think what really helped it happen was the fact, that hey, it was right. People were beginning to have serious questions about the war. It was costing—Chicanos were coming home in body bags. And the people started thinking about that.

And then the other thing was that there was all this upheaval anyway, and people were thinking in ways that were different. So it wasn't the idea of just one organization, it was the thinking of a lot of different organizations and people with a lot of different points of view.

And the last thing I want to say about that is this—at the march itself, whole families came, from the grandmother to little kids. It was just amazing. I think, from my understanding, it was along the lines of the protests against Prop 187—how people brought the whole family and they all marched in the street. The Moratorium was like that.

Q: It surprised people that so many people came down for the march—like how did that happen? I heard about people from Missouri and from Kansas, like you said. How did the word get out over there, that this whole big thing was going to happen? That they would all come down for this whole march in L.A.?

Chicano Moratorium rally, August 1970. Photo: Luis C. Garza/Chicano Studies Research Center at UCLA

A: There were a couple of things like I said. There was all this experience from the anti-war movement. There was Chicano organizations from different campuses. But the main thing was this: it was the right thing to do. You know what I mean? In other words, people responded, not because somebody said something, but because they felt it deep. And they didn't want it to go on anymore. And there was kind of a yearning for people to come together. And I think that is the other part of it. Because this had never happened before, and the thing I raised earlier is that, where there was no organization, people went and organized there. There were a lot of small organizations all around the country. And what united everybody was opposition to the war, and for some people opposition to the way Chicanos have to live.

It was a big awakening for people when they began to find out about the conditions—for example at UCLA in 1967, they had never graduated a single Chicano from the Medical School. All around the country there were different things, police murders, exploitation, the last hired, first fired, the worst jobs, all that kind of shit. People had suffered an oppression that they suffered in common. And they had a desire to get together to try to do something about it. I think it was a big adventure for a lot of people. In many cases they didn't know anybody here, and they came. It became a big factor when the police attacked the march.

Q: One thing some people say to us is that if people get too radical—the people, the community is not going to support them. And also, there's the whole question of the involvement of the youth, right—"Well we don't want them to get arrested, we don't want them to get hurt, we don't...”—all these things. I'm thinking about this in light of what happened at the Moratorium, a situation where you know there is mixture of people there. There is the masses that are out there, like proletarians are out there, students are out there. And when the police came down—when they got really heavy, people supported the youth. We read this story about this man who let all these young people into his backyard, and a sheriff comes in and he wants to like do whatever. And this old man puts his chest in front of the sheriff's shotgun and says, "You're not coming in." And he was ready to defend all these strangers with his life. What else happened? What was the mood of the people, people who didn't even know each other? Like defending each other, willing to like lay down their lives for, not just the cause, but for other people as well.

A: Yes, well you hit a couple of things. One of them is that people have to realize, these people who run things are willing to send people to die to further their domination of the world. They don't really have the people's interest at heart. That's not a very good expression of being concerned about your welfare, sending people to die in a genocidal war. That has to be answered. There is a point that people have to support what you are doing. And part of what happened at the Moratorium was the police attack was so unjust and so completely unjustified that people who ordinarily, maybe wouldn't have gotten involved, did get involved and there is that example of that older man that you are talking about.

The point I want to make is this—when the people have a justifiable hatred and an anger of being treated like this, that's gonna find expression. There were a lot of examples like that. This older man came up—soda was in bottles in those days—and he brought us empty coke bottles by the case and he said when you guys get done with those, there's more in the back. He was a small merchant, he wasn't a flaming radical, he wasn't like working for the overthrow of the government. He was just a small merchant who had a little shop right there on the same street where much of the fighting went down. So he saw what happened on Whittier Blvd. every day. He could look through his windows and see life as it passed in front of his store. The first chance he got of allying himself with people who were trying to do something about all that, that's what he did. Now I don't think he was an initiator of the Moratorium, he wasn't out there really doing some of the stuff that some of the younger people were, but he supported them because he knew it was justified. And we have to uphold that. And that's the other part that I think is important. We have to support people when they fight back against how they have to live. We can't tell them no, you can't do that.

You had all these people, they didn't know this town. I used to hang around some of the places where this was going on, so I knew the area. But there were all these people who came here who had never been here before. One of the reasons you know there was a lot of unity was the way people reacted to the attack. The police were functioning like "robo cops." They were very deliberate. And we had to defend ourselves. All these people that didn't know each other, that had never worked together or anything like that. All of sudden none of that mattered. The only thing that mattered was fighting back. And the police got very demoralized. They didn't expect what they got. Part of it is that they had a arrogant attitude toward the Chicano people. They had an attitude that they weren't capable of thinking, of responding. They thought that once they attacked, that was going to be the end of it. Everybody would just get scared and run away.

Q: What were the cops so scared of about the march, why did they want to disperse it?

A: You mean why did they attack it? It's important to go back to a couple things. One was what happened at Kent State and Jackson State. The United States all around the world was under attack. They had the war in Vietnam, they had all the rebellions in the cities. Watts had already gone up. Black people had come to within eight blocks of the White House, they were going to burn the fucking thing down. They were under siege. They could not allow an aroused Chicano people to take matters into their own hands. And that was the reason for the attack. There should be no misunderstanding about that.

L.A. had this frontier thing. They did not allow demonstrations. They didn't tolerate demonstrations. They didn't want the city to get like other places. They had a very volatile situation and they were trying to control it. That's why they attacked.

The other thing they did, was they used the Moratorium as a pretext—they killed three people. Two of them were masses, and the third one they killed was Ruben Salazar, who was shot by a Los Angeles Deputy Sheriff. He was writing a book on police brutality. The year of the Moratorium 11 people had died in police custody in the Sheriff's Department substation—including one guy who supposedly died from a fall down the stairs—and a lot of other really stinky shit. And they used this as a way to go after him.

Several weeks before the Moratorium, I went to L.A. to see some friends of mine. What happened is two Mexicanos from San Leandro had come to L.A. and had been killed by the LAPD. Two immigrants had been shot and killed. There was a committee formed, and we asked if they had any film footage. Not of the shooting, because nobody had film footage of that, but of the events afterwards. We wanted it for the committee.

We met Ruben Salazar, and he told us that the guy that covered the story is taping and will be by in a couple of hours. He said, you're students, you're probably hungry, I'll buy you guys lunch. So Ruben Salazar bought us lunch, and he told us that he had been threatened by the Sheriff's Department, that he was writing a book on police brutality and when they found out he'd been doing interviews, they told him, you better knock that shit off.

Ruben Salazar came to L.A. to cover what was called the "Chicano Beat" for the Los Angeles Times. Before that he had been the Times chief of the Latin American bureau. When he first began to cover the "Chicano Beat" he knew very little about the conditions Chicanos faced. He came from a family that was well off.

We would talk about what the cops used to do and he would look like he could hardly believe what we were saying. He began to change as he saw the way the cops acted. After a while he began to see for himself and his reporting changed and so did his attitude. At the time he was killed he was sitting down drinking a beer. People have photos of the sheriff that killed him firing the killing shot. Nothing was done to the cop. It was either one of the greatest coincidences in history or they had planned it before the Moratorium.

They used the Moratorium as an excuse to kill him. I think this whole thing was premeditated and preplanned. He's dead because they don't want to have an aroused population. In other words, the imperialists can't let people get out of bounds. They maintain their control over people in a variety of ways. One of them is to give the illusion that they have certain democratic rights. Because otherwise their dictatorship is open and naked and nobody is going to accept it. On the other hand, they can't let it get beyond a certain point. At this time, they were like totally freaked out and that's why they attacked the march. And from their perspective, it made sense because they didn't want things to get any further.

It was like what happened in Mexico City in 1968 when they killed all those students. Those students, they weren't trying to overthrow the government or anything like that. But the United States wanted to have a nice peaceful Olympic Games, and they rained repression on people way beyond the level—given the demands. That's what I think happened at the Chicano Moratorium, they didn't want it to get out of hand. Plus, I think they thought maybe they could make some gains by attacking it.

Q: There were different Chicano organizations there. Were there any arguments between organizations about the march?

A: I think it's not correct to zero in on that. Because whatever the organizers did or didn't do, I think the Chicano Moratorium mainly was a product of the suffering and the determination of the Chicano people to end it—that's what happened.

I think everybody got surprised at the turnout. I think nobody, nobody anticipated it was going to turn out like this. There were people that would have been happy if a couple thousand would have shown up. It went beyond anybody's expectations for a couple reasons. One, you know, we had never done anything like this, we didn't know how it was going to turn out. I always myself think it was an underestimation by many of the organizers. I think that that was one of the hallmarks of the movement. Always underestimating what the Chicano people were capable of doing.

The important thing is what the Chicano people did that day. They came out and they did it. This was known in the whole world. This was an important event. The Vietnamese people certainly welcomed it. And later on when the United States had to sign the peace treaty, this is one of the reasons why they had to. They were facing revolution at home. They had over 100 cities burned down, and in Vietnam, they had fragging. Which I don't know if you guys know what that is. Fragging is when, you know the GI's just wanted to go home. They want to get home. They don't want any war shit. So sometimes the officers would say, well, we have to go out on patrol, and so tomorrow morning, we are going to go out, and the guys would try to talk them out of it. And if the guy insisted, the guys—some time during that night, a hand grenade would go off where he was at, and he wouldn't be there in the morning. So they didn't have to go out on patrol. That's called fragging, where the GI's kill their own officers. And it got so bad that they began to realize that they did not have a reliable army in Vietnam. Because look, when you give people guns, which you have to do so they can shoot the other side, they have those guns. And if you think you are going to die, and you've got a gun, and this guy comes along and says you have to do something that you think may mean you ain't going to come back, why the fuck should you do what he tells you. You don't have to. And they began to have an unreliable army there.

And then you had stuff like the Chicano Moratorium. Up to this point, Chicanos by and large served in the military, proud warriors. And to have this happen was one of the reasons why they began realizing we cannot win this war, we better sign the peace treaty.

And that lets you put in perspective a couple of things. One, why you have to actually link the struggle to what's going on. You can't pretend like there's not a connection between the struggle of the Chicano people and the struggle of the Vietnamese people. The United States didn't lose sight of that, they got it. They thought, "Jesus Christ, those people over in Vietnam are spreading all this shit over here. We can't get these people to go in our military like we used to, they are saying they don't want to serve." Manuel Gómez wrote a poem saying he would not serve in the military. That was heavy shit. That was all part of the Chicano Moratorium, it was important.

Q: What do you think about this generation today who have been on the front lines fighting against all these attacks that are coming down—what do you think are some of the lessons that this generation needs to grab onto from the Chicano Moratorium?

A: I think the main thing about the Chicano Moratorium is we uphold it. We uphold it because once it was attacked, people fought back. I don't think the summations that were put out by most people were very dialectical. People tended to only look at the fact that it got attacked. But to me, it contained some important lessons, that it's right to rebel against reactionaries. You have right on your side and you act, you have allies.

I once read an interview with Mao Tsetung where he said the main lesson is you can never give up, never. You don't know when you start where it is going to end up. But you do know they are not going to stop treating us the way they do. We are in a position to do something about it, right here in the belly of the beast.