Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.”

3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better:

1) People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.

2) People have to dig seriously and scientifically into how this system of capitalism-imperialism actually works, and what this actually causes in the world.

3) People have to look deeply into the solution to all this.

Bob Avakian

May 1st, 2016

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

THE CRIME

In early 2018, a construction crew in Sugar Land, Texas, a fast-growing suburb 20 miles outside of Houston, accidentally discovered 95 shallow unmarked graves. The 94 Black men and one Black woman whose remains were found were as young as 14 and as old as 70 when they died. Rusted farm tools and chains were also found at the site, including chains with swivels on them, likely used in chain gangs.1 The bodies had been buried over 100 years ago in pine boxes just two to five feet under the earth’s surface.2 This accidental find has now revealed something of their painful story and a gruesome chapter in the ugly history of America’s treatment of Black people.

Archeologists who have begun to study this site date the bodies back to 1878-1911. They found signs of horrific injuries on the skeletons, ranging from bone infections and “shackle poisoning” (when human skin rubs against rusty metal shackles causing potentially fatal infections) to healed bone breaks and “bones distorted by heavy labor and muscles torn away from the skeleton,” according to the New York Times.3 Many of the bones unearthed were deformed in the same ways, which indicate that they bore the repeated stress of incredibly hard labor.

These remains belonged to prisoners—leased convicts—who had been forced to work in virtual slavery for Sugar Land’s Imperial Sugar Company, once this country’s leading sugar producer. Some of them may have been former slaves. Were these human beings literally worked to death and then unceremoniously disposed of?

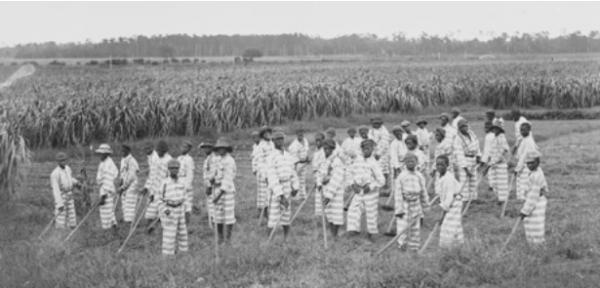

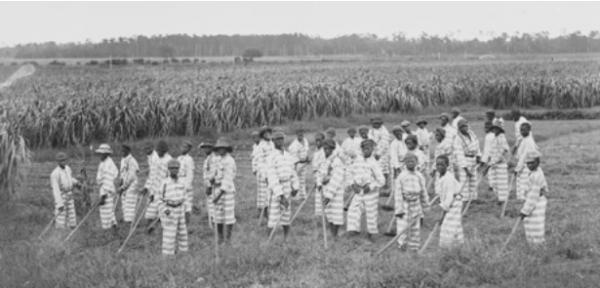

Child prisoners used in leased-convict labor, 1903. Credit: John L. Spivak, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65943203

Sugar and Slavery

Sugar was first produced by slave labor in 1452 off the coast of Africa. By 1600, sugar was being produced by slaves on plantations in Brazil, and by 1803, following the Louisiana Purchase, slave-based sugar production began spreading in the U.S.4

By 1850, sugar accounted for as much as a third of the economies of major European powers.5 It also came to be known as “the slaughterhouse of the trans-Atlantic slave trade by killing more people more rapidly than any other kind of agriculture,” Brent Staples writes in the New York Times.6 Historian David Eltis estimated that about “70 percent of the 12 million or so captives” from Africa were shipped to sugar colonies in the Caribbean and South America and to U.S. states like Texas, Florida, and Louisiana (where “the average life span of a mill hand was said to be only seven years....”).7 By the 1850s, sugar was a major industry in the southeast Brazos River region of Texas where Sugar Land came to be located. It came to be known as “the sugar bowl of Texas”—or as the “hellhole on the Brazos.” The U.S. sugar industry depended on slave labor for its profitability, and the end of slavery threatened the whole industry.

“Neo-slavery” or Slavery by Another Name

Slavery was formally ended in 1865 in the U.S.—except, under the 13th Amendment, for prisoners. Right after the Civil War (1865-1866), all Southern states passed laws (“black codes”) under which Black people, especially young Black men, were arrested in sweeps or individually for trumped-up or petty offenses such as loitering, breaking curfew, selling crops at night, flirting with white women, gambling, drinking, or vagrancy (inability to prove employment). With the end of Reconstruction in 1877, former slave owners and capitalists in the South quickly seized on these laws to institute a system of leasing convict labor from prisons that literally re-enslaved tens of thousands of Black people.

The Texas sugar plantations were profitable because they depended on slave labor. Abolition crushed the industry, but the convict leasing system resurrected it in a form that can legitimately be seen as more pernicious than slavery: Slave masters had at least a nominal interest in keeping alive people whom they owned and in whom they held an economic stake.

By contrast, when a leased inmate died in the fields, managers who had contracted with the prison system for a specific number of bodies could demand a replacement. Beyond that ... the working conditions on the plantations in Fort Bend County, where the Sugar Land dead were discovered, were as bad or worse than they had been on the slave plantations....

—Brent Staples, “A Fate Worse Than Slavery Is Unearthed,” New York Times, October 27, 20188

According to “Hell-Hole On The Brazos: A Historic Resources Study Of Central State Farm, Fort Bend County, Texas,” two former slave owners and Confederate officers, Edward Hall Cunningham and Littleberry Ellis, formed a partnership in 1875, grouping their sugar plantations together. They pioneered the convict-leasing system and became the biggest Texas sugar growers by signing a five-year contract to lease the entire prison population of Texas.9

“In 1878, Cunningham and Ellis procured a 5-year state contract leasing the entire prison system and put convicts to work in their sugar cane fields,” researcher Amy Dase found. “By 1882, more than one third of the state’s inmates, roughly 800 prisoners, worked on 12 of Texas’s 18 sugar cane plantations through the Ellis and Cunningham contract. The combined Cunningham and Ellis properties had a workforce of more than 500 prisoners at one time.”10

Even as their partnership dissolved and the plantation passed through different hands, the system of convict leasing continued as Sugar Land (named after Imperial Sugar Company) became a company town by the turn of the 20th century and was incorporated as a city in 1959.

Leased prisoners worked barelegged in wet cane fields, clothed in striped rags, in mosquito-infested swamps full of alligators and other dangers, and hoisted cane stalks into mule-drawn wagons for delivery to sugar mills. One author noted they were “dying like flies in the periodic epidemic of fevers.”11

Leased prisoners unloading a cane car at the Imperial Sugar Company’s mill, circa 1900. Credit: Sugar Land Heritage Foundation

Southern states used convict leasing during the Jim Crow era and, typically, 90 percent of prisoners in the convict-leasing system during that time were young Black men (who made up 60 percent of the Texas prisoner population).12 It is estimated that between 1866 and 1912, more than 3,500 Texas prisoners—mainly those leased into forced labor—died. When prisoners died, the companies would just go back to prison authorities and tell them “you owe us another prisoner.”13 Historian Robert Perkinson calculates that more Black people died in the South from this convict-leasing system than from lynchings in the same period of time.14

Digging at a construction site revealed a mass grave of 95 bodies of convicts leased as slave labor to Imperial Sugar Company. (Photo: Houston Chronicle)

The Cunningham and Ellis contract lasted for five years (1878-1883). In 1909, the state of Texas opened its Imperial State Prison Farm on the same land that had been the Imperial Sugar Company. It was the first prison farm owned by the state of Texas. While the name and ownership changed hands, prisoners continued to be forced to work on this sugar plantation in near-slavery conditions.

Conditions for prisoners who worked in the cane fields were horrific—they often were forced to chop cane until they “dropped dead in their tracks.” Many suffered from heatstroke, cuts from hacking down 10-foot sugarcanes with razor sharp 16-18 inch machetes, mosquito-borne epidemics, frequent beatings, and a total lack of medical care. This resulted in a high mortality rate, with prisoner laborers as young as 14 worked to death at Sugar Land.

Bill Mills, a (white) prisoner who did 25 years, with five years at Imperial Prison Farm, recalled:

Human lives were not of value ... “I saw more cruelty and inhuman treatment in those five years than I have seen in the other 20 years in prison.” Prisoners there constantly faced beatings with bats that were “two-foot long leather strap mounted securely on a wooden handle.” He recounted how for first time minor offenses, a prisoner was held in a dark cell from Saturday night to Monday morning (36 hours) with up to 8 other men, in a “room about eight feel long, six feet wide, and six feet high. It had no bedding,” no clothing “except a gown,” and no food except “one cup of water and one piece of corn bread Sunday at noon.” For a second offense, prisoners were chained by the wrists and hoisted to hang for 3-4 hours depending on ...“whether he became unconscious.”15

Author Douglas Blackmon argues that “...in truth, since the beginning of the 20th century, a new form of forced labor involving hundreds of thousands of people, and terrorizing hundreds of thousands of other people, had emerged in the South, that amounts to what I call ‘neo-slavery,’ and we should call it what it was, the age of neo-slavery.”16 He finds that “There’s no place in America that proves that more powerfully than Sugar Land.”

City of Sugar Land, Texas, and City Manager Allen Bogard claimed Imperial Sugar and its convict labor system had nothing to do with his city’s development: “Our history as a city begins fifty years ago. The Imperial Sugar Company, of course, played an important part in our early history. But the fact is that this area would have developed with or without the Imperial Sugar Company.” A bitter debate erupted in Sugar Land after the remains of enslaved sugar workers were discovered. City officials wanted to move them to a nearby cemetery, while members of a city-appointed task force rightly argued that a historical find of this magnitude should be memorialized on the spot where it was discovered.

THE CRIMINALS

State of Texas. One of the last states in the U.S. to officially end slavery and the first to adopt a convict-leasing system.17

Imperial Sugar Company and two of its early developers, Edward Hall Cunningham and Littleberry Ellis, slaveholders turned Confederate generals in the 4th Texas Infantry Brigade—a brigade that supposedly distinguished itself in the Civil War by acting as shock troops for the Confederate army. Their families’ wealth was derived—literally—from the blood and bones of Black people, especially through the convict-leasing system. This enabled them to become sugar barons and part of a new wave of capitalists of the South. The history section of the official website of today’s Imperial Sugar Company states that the company “has a long and rich heritage”—but makes no mention of the Black slaves, slavery, or convict leasing.

The 39th U.S. Congress (1865) ratified the 13th Amendment which formally abolished slavery and involuntary servitude “except as punishment for crime.” This formed the legal and political basis for forced prison labor, including convict-leasing, to flourish, down to today.

U.S. Steel, Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, Imperial Sugar Company, and many more private corporations—from mine owners to railroad barons—who amassed huge amounts of capital through convict labor. Blackmon documents a typical case:

On March 30, 1908, Green Cottenham was arrested by the Shelby County, Ala., sheriff and charged with “vagrancy.” After three days in the county jail, the 22-year-old African-American was sentenced to an unspecified term of hard labor. The next day, he was handed over to a unit of U.S. Steel Corp. and put to work with hundreds of other convicts in the notorious Pratt Mines complex on the outskirts of Birmingham. Four months later, he was still at the coal mines when tuberculosis killed him.18

THE ALIBI

During the Jim Crow years, forced convict labor was justified on the grounds that imprisoned Black people were inherently criminals without rights. Since it was expensive for prisons to feed and clothe convicts, it was justified to lease prisoners out so the state could earn revenue while companies could work, feed, and clothe the prisoners. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, H.B. Frissel, the white superintendent of Virginia’s all-Black Hampton Institute, expressed a common rational for convict leasing:

While it kept negroes from being educated, it also kept them from being criminal.... When emancipation came, the naturally depraved and criminal class of negroes were let loose and deprived of this restraining influence of the slavery system. Such men began, naturally, to confound license with liberty, and they have instinctively degenerated since slavery days.19

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE

After the Civil War, the Southern economy was in shambles, and there was a great demand for a labor force that could be super-exploited. And the ending of Reconstruction signaled that the victorious capitalist North could only recohere and “unify” the country on the basis of maintaining white supremacy in new forms. These two forces—capitalism and white supremacy—drove the formation of the convict labor system of Jim Crow.

The criminalization and forced enslavement of tens of thousands of Black people was part of robbing a whole people of their full humanity and formed another ideological justification for the continuation of white supremacy following the end of chattel slavery. As Douglas Blackmon observed, pointing to a rationale used to this day, “Sympathy for the victims, however brutally they had been abused, was tempered because, after all, they were criminals.”

1. “Remains of 95 Africa-Americans Forced Laborers Found in Texas,” Brigit Katz, Smithsonian Magazine, July 19, 2018. [back]

2. “You can’t fight racism without looking it in the eye,” Houston Chronicle, January 19, 2019. [back]

3. “Documenting ‘Slavery by Another Name’ in Texas,” New York Times, August13, 2018. [back]

4. “Sugar Plantations,” Spartacus-Educational.com. [back]

5. How Sugar Changed the World, LiveScience.com. [back]

6. A Fate Worse Than Slavery, Unearthed in Sugar Land, Brent Staples, New York Times, October 27, 2018. [back]

7. ibid. [back]

8. ibid. [back]

9. “Hell-Hole On the Brazos: A Historic Resources Study of Central State Farm, Fort Bend County, Texas,” Amy E. Dase, September 2004. [back]

10. ibid. [back]

11. “Bodies believed to be those of 95 black forced-labor prisoners from Jim Crow era unearthed in Sugar Land after one man’s question,” Meagan Flynn, Washington Post, July 18, 2018. [back]

12. The Reason Why: The Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition 1893, chapter III, The Convict Lease System, Ida B. Wells. [back]

13. Op. Cit, Flynn, Washington Post. [back]

14. ibid. [back]

15. “‘Hell Hole on the Brazos’ an introduction to convict labor,” Richard A. Vogel, Fort Bend Star, August 14, 2018. [back]

16. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, Douglas A. Blackmon, Doubleday Press, 2008; Slavery by Another Name PBS Documentary narrated by Laurence Fishburne, 2012; “Douglas Blackmon interview with Michael Slate,” revcom.us, June 15, 2008. [back]

17. “Horrific convict-system exposes dark truths about American history,” Jeffrey L. Boney, Amsterdam News, September 9, 2018. [back]

18. From Alabama’s Past, Capitalism Teamed with Racism to Create Cruel Partnership, Douglas A. Blackmon, Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2001. [back]

19. Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, David M. Oshinsky, Free Press, 1996. [back]