Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.”

3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better:

1) People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.

2) People have to dig seriously and scientifically into how this system of capitalism-imperialism actually works, and what this actually causes in the world.

3) People have to look deeply into the solution to all this.

Bob Avakian

May 1st, 2016

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

The Oppression of Black People and Other People of Color

The Oppression of Black People and Other People of Color

From the speech by Bob Avakian: Why We Need An Actual Revolution And How We Can Really Make Revolution

Watch the complete speech here.

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, one of three “Reconstruction Amendments” passed as the Civil War ended, says that, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This marked a radical transformation from previous law and entrenched custom in all the U.S. Even in the North on the eve of the Civil War, only five states, all in New England, allowed Black men to vote.

During the short period of Reconstruction, Black people in the South, along with some whites, fought heroically for their constitutional right to vote. About 1,500 Black men were elected to various state and local offices across the country. For the first time, Black people sat in the U.S. Congress.

This was bitterly opposed from the beginning. Vengeful white supremacy was the open ideology of the Democratic Party, which dominated the South. Armed vigilantes, many of them former Confederate soldiers, were coalescing into the KKK, and acted as the armed wing of the Democrats. They carried out murderous terror across the South. (Before and during the Civil War, the Republican Party was the party of those ruling class forces that to one degree or another opposed slavery, and that, for about a decade after the war, supported more rights for Black people. But for over a century since then, the Republicans, like the Democrats, had been a party of white supremacy.)

More recently, relentless efforts to suppress Black people’s votes and to rally whites around white supremacy have been a hallmark of Republican campaigns since Richard Nixon launched his “Southern Strategy” in 1968. Lee Atwater, advisor to presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush, described it this way in a 1981 interview: “You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968 you can’t say nigger—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like uh, forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff…. Now you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites… ‘We want to cut this,’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘Nigger, nigger.’”1

Today the Trump/Pence fascist regime is continuing this ugly all-American tradition in new ways—openly supporting white supremacists, organizing its fascist foot soldiers to intimidate Black and Latino people at the polls, and launching multipronged efforts costing tens of millions of dollars to keep Black and Latino people from voting at all.

The Crimes

New Orleans, July, 1866: A mostly unarmed group of Black and white delegates to the Louisiana Constitutional Convention who were protesting the passing by the state legislature of white supremacist laws, including denial of the Black vote, were attacked by white racists. The mob not only attacked delegates but others who had nothing to do with the convention, killing 150 to 238 people. Sketch by Theodore R. Davis, Courtesy NY Public Library

New Orleans, July 1866

In the spring of 1866, the Louisiana State Legislature, entirely composed of white supremacists, passed a set of “Black codes”—laws designed to restrict and deny Black people's freedom. Among other repressive measures, this “code” denied the right to vote to Black men. Black and some white delegates to the Louisiana Constitutional Convention—then meeting in New Orleans to draw up a new charter for the state after the end of slavery—were furious.

As the mostly unarmed delegates marched to Mechanic’s Hall, the site of the convention, they were attacked by a heavily armed mob consisting of ex-Confederate officers and soldiers, white supremacists, and most of the New Orleans police, led by the city’s mayor. The Black and white delegates beat back the mob and drove them out of the hall, where they had taken refuge. But reinforcements with more ammunition arrived for the racists, and they again attacked Mechanic’s Hall, this time successfully. They also rampaged through the streets around the hall, killing people who had nothing to do with the Convention. Estimates of the number of dead range from 150 to 238.2, 3

Eutaw, Alabama, October 1870

Throughout the summer of 1870, as November elections for governor neared, Klan terror ripped through the area around Eutaw in Alabama’s Black Belt. At least five Republicans, four Black and one white, were lynched in July. That same month, Gilford Coleman, a prominent Black Republican, was pulled from his home by Klan night riders and his body mutilated. In October, an unarmed outdoor meeting of about 2,000 Republicans, mainly Black people, was attacked by Klansmen who fired into the crowd, killing at least four and injuring many more. A contingent of federal troops did nothing to intervene. Most Black people in the area stayed away from the polls in November, and the open white supremacist won. Alabama officials took no action against the murderers, and although a federal grand jury returned indictments against 20 people, they were never convicted.4

Colfax Massacre: 1873: A drawing from Harper's Weekly depicting Black people collecting the bodies of the murdered after the massacre.

Colfax, Louisiana, 1873

On April 13, Easter Sunday, over 300 heavily armed white men, mostly former officers and soldiers in the Confederate Army, shot, stabbed, burned, and maimed Black people seeking shelter in a courthouse. At least 150 people were murdered in what historian Eric Foner described as the “bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era.”5 The terror came in the midst of a bitterly contested election, and was part of a campaign to prevent Black people from voting, and to institutionalize white supremacy at all levels of state and parish (county) governments.

None of the murderers, who were widely known in the area, were tried in state court. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the convictions of the three murderers who had been tried for violating the civil rights of people they killed on the grounds that federal law cannot protect Black people from violations of their civil rights (or mass murder!) by mobs, only violations of those rights by government agencies. This opened the door to rampant, unpunished lynching that raged across the South for the next 80 years. 132 years later, in 2005, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution expressing its “remorse” for having never acted to outlaw lynching!6, 7

Hamburg and Ellenton, South Carolina, 1876: Klan murder and violence spread across central South Carolina, terrorizing Black people at political gatherings and church meetings. (Drawing from Harper's Weekly)

Voter intimidation, 1876. (Drawing from Harper's Weekly, October 21, 1876)

Hamburg and Ellenton, South Carolina, 1876

As another election for governor approached, a group of white farmers went to court to complain that their passage along a road had been blocked by a Black militia. About 100 armed whites came to the court on the appointed hearing date, opened fire, and killed four Black people. During the same period a reign of Klan murder and violence spread across central South Carolina, terrorizing Black people at political gatherings and church meetings. While several white assailants were killed in these raids, estimates of the murdered Black people range from 30 to over 100 or more. They included Simon Coker, a prominent Black state legislator. A leader of the racist attacks in both Hamburg and Ellenton was Ben Tillman, a life-long white supremacist who went on to be a founder of Clemson University, governor of South Carolina, and U.S. senator. While in the Senate, Tillman defended lynching and boasted of his involvement in the murder of Black people and consolidation of white supremacy in South Carolina.8

Wilmington, North Carolina, 1898: A white mob led by a former Confederate officer burned down Black-owned businesses and killed at least 60 people.

Wilmington, North Carolina, 1898: A white mob led by a former Confederate officer burned down Black-owned businesses and killed at least 14 people.

Wilmington, North Carolina, 1898

Wilmington at this time was the largest city in North Carolina. A majority of its population was Black. Black people were prominent in the political and business leadership of the city, at a time when white supremacist Democrats dominated in the state. The presence of a largely Black leadership of the city was intolerable to these racists, who had proclaimed, “North Carolina is a WHITE MAN’s State and WHITE MEN will rule it…” In early November a “white man’s rally” in Wilmington drew over 1,000 armed people. At around the same time, local businesses refused to sell arms or ammunition to Black people in Wilmington.

On November 10, on the pretext that an editorial in a Black-owned newspaper had insulted white women, a wealthy former Confederate officer led a mob of 400 whites that stormed through downtown Wilmington. They burned down Black-owned businesses, broke out windows, and killed at least 14 people. An estimated 2,000 Black people were forced to flee the city. Black authorities in the local government were replaced by whites, and the leader of the mob became mayor.9, 10

Miami, Florida, 1940: Effigy of a black man hanged with a sign reminiscent of the lynching of July Perry in Ocoee, Florida, 1920.

Ocoee, Florida, 1920

Throughout the summer and early fall of 1920, some Black people associated with the Republican Party were part of an effort to register voters for the upcoming presidential election. This was the first U.S. election in which women could vote, and the core of activists made a particular effort to register Black women. They wanted to contribute to breaking the stranglehold that the Klan and the openly white supremacist Democratic Party had on Central Florida.

But they met fierce opposition from the entrenched white power structure. The Florida History Project wrote that the day before the election, “… with robes and crosses, the Klan paraded through the streets of the two Black communities in Ocoee late into the night. With megaphones they warned that ‘not a single Negro will be permitted to vote’ and if any of them dared to do so there would be dire consequences.” Shortly after Moses Norman, a Black man, attempted to vote, hundreds of white WWI veterans from throughout the county swarmed into Ocoee. They eventually burned down almost all the buildings in north Ocoee, where most Black people lived. Many Black residents resisted, but they were outnumbered and outgunned. As many as 60-70 were killed by the racist mob, and hundreds were driven from the town. The mob descended on the home of July Perry, Norman’s friend, because they heard that Norman had fled there. Perry, and possibly other people, defended themselves from inside the house, killing two of the mob and wounding the Ocoee police chief.

The lynch mob fled, but returned with a caravan of 50 cars filled with Klansmen, who overwhelmed July Perry. They brutalized Perry and brought him to the city jail. Later that night, with the cooperation of the sheriff, the mob pulled him from his cell, chained him to a car, and dragged him through the town before hanging and shooting him. They left his body there, with a sign saying, “This is what we do to niggers who try to vote.”

As late as 1959, a sign reading “Dogs and Negroes Not Welcome” was posted at the city limits of Ocoee.11, 12

The Civil Rights Era

The “Black codes” enacted in the late 1800s and upheld repeatedly by the Supreme Court had devastating impact for the next 70 years. For example, in 1958, at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, Gadsden, a majority Black county in Florida’s panhandle, had a population of 12,261 Black people. Seven of them were registered to vote. Similar situations existed across the South. By the early 1960s, youth and others launched courageous struggles to confront and overcome this situation.

McComb, Mississippi, 1961

Activists with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized voter registration in McComb and surrounding areas of southwestern Mississippi. Authorities in Mississippi, like elsewhere in the South, “maintained a savage system of oppression, repression, retaliation and legal restrictions to keep Blacks politically disenfranchised…. Brutal violence, often deadly, and swift economic reprisal were used to deter Black men or women who dared attempt to gain the political franchise.”

Brenda Travis, a 15-year-old high school student in McComb, canvassed the streets with the SNCC voter-registration workers. She also led a sit-in at a local diner that didn’t serve Black people—she soon was sentenced to a year in the state juvenile prison and expelled from high school. The Klan, the Citizens’ Council, and racist whites in general reacted violently to the Black people trying to register, and “night riders” armed with rifles and shotguns prowled through the Black communities. As tension and violence increased throughout the summer, two SNCC workers were assaulted by a mob in downtown McComb and thrown in jail. In an outlying area, Herbert Lee, a local man working with SNCC, was murdered by a state representative in broad daylight. An all-white jury ruled that his murderer acted in “self-defense.”13, 14

Canton, Mississippi, 1964

Canton’s Freedom House, in northern Mississippi, became a center for students and others organizing to overcome deeply institutionalized Jim Crow. In 1963 and 1964, a group called the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) led a voter registration drive as part of Mississippi Freedom Summer. They faced constant threats, harassment, and dismissal. Over an eight-month period in 1963, when COFO prepared more than 1,000 people to register to vote at the Canton courthouse, only 30 were accepted. The youth were repeatedly assaulted by both Klan and the police, sometimes acting together. Many were arrested and sent to the county jail and to Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm prison. In May 1964, the Klan bombed the Freedom House. In her memoir, Coming of Age in Mississippi, author Ann Moody described how she and others had taken to sleeping in the cornfields behind the house because of constant threats and attacks—fortunately, no one was in the house the night it was bombed.

In 1964, people involved in Freedom Summer and others came together to form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. In the face of opposition from the official, segregationist Democrats, and the murderous violence that reached a terrifying pitch in Mississippi that summer, they selected a group of 68 delegates, 64 of them Black, to represent Mississippi at the National Democratic Convention in Atlantic City. When they got there, the Freedom Party delegates rejected a “compromise” proposed by President Lyndon Johnson that would have allowed two to serve as “at-large delegates.” The openly white supremacist, segregationist delegation represented Mississippi at the convention.15, 16

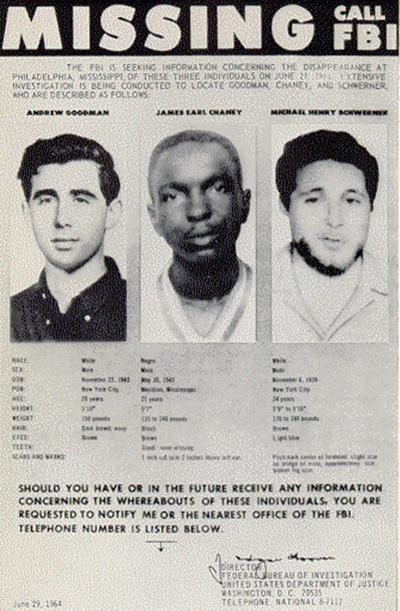

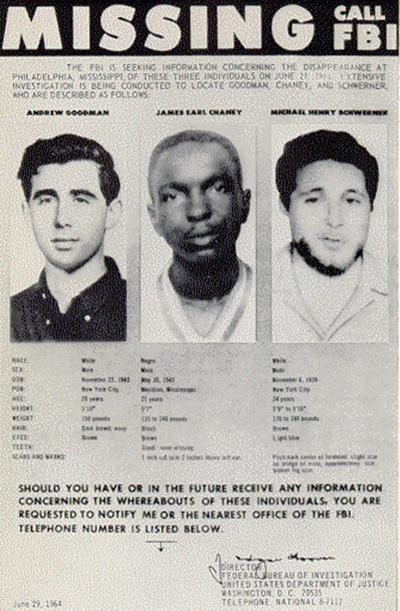

Neshoba County, Mississippi, 1964: FBI poster of three missing civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Henry Schwerner.

Neshoba County, Mississippi, 1964

James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were also part of the Freedom Summer voter registration campaign. On June 21, the three traveled from Meridien, Mississippi to the town of Longdale, where the Mt. Zion church had been burned down—by the Klan, as it turned out. The three men had recently spoken at the church and urged parishioners to form a Freedom School at it. They knew they were heading into a perilous situation. Schwerner told people in Meridien, “If we’re not back by 4 p.m., then start trying to locate us.”

They were arrested for an alleged traffic violation in Philadelphia, Mississippi, after they left Mt. Zion. The police held them in jail for several hours, then, at night, followed the three out of town and alerted a lynch mob to join them. The car with Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman was forced to stop just before leaving Neshoba County. The three men were seized by the mob, then shot, beaten, and buried under an earthen dam. That night a Philadelphia cop who organized the lynch mob told them, “Well, boys, you’ve done a good job. You’ve struck a blow for the white man. Mississippi can be proud of you.”

The murders of the three civil rights workers became news across the country. A massive search was launched, and during it, the bodies of eight other dead Black men, including two students who “disappeared” in May 1964, were found in the swamps and woods of Neshoba County—their deaths, likely by lynching, had never attracted national attention. A search went on for almost two months before their bodies were found.

The state of Mississippi refused to try the lynchers—who included Klansmen, Philadelphia police, and Neshoba County sheriffs—for murder. In an October 1967 federal trial, seven were convicted of violating the civil rights of the three murdered men. None served more than six years in prison.17, 18

Selma, Alabama, 1965

In February, 27-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson participated in a demonstration for voting rights of 500 people in Marion, a town near Selma. Police viciously attacked the march, and when Jackson tried to protect his mother, he was shot in the abdomen. Jimmie Lee Jackson died eight days later in a Selma hospital. The first of the famous Selma-to-Montgomery marches was organized in the wake of Jimmie Jackson’s murder. Hundreds of people marched in protest of his murder, and as part of the Selma voting project. The second march—“Bloody Sunday”—was memorialized in the movie Selma. It was viciously attacked by police and Alabama state troopers as they crossed a bridge over the Alabama River. The cop who murdered Jimmie Lee Jackson was not indicted by a local grand jury until 42 years after Jackson’s death.

The Alabama Klan also sent a murderous message to the growing number of white people who had come to Selma to participate in the marches. Viola Liuzzo, 37 years old, traveled from Detroit before the first march, and helped coordinate logistics for people coming into Alabama. She was shot and murdered as she returned to Selma after driving some people to an airport in Montgomery. An FBI agent was in the carload of Klansmen who murdered Viola Liuzzo.

James Reeb was a 38-year-old Unitarian minister who traveled from Boston. He and two other ministers were savagely beaten by a pack of racists as they left an integrated restaurant in Selma. Reeb suffered severe head injuries. He had to be driven two hours to Birmingham—the hospital in Selma that treated Black people did not have the capacity to treat his level of injury; the white hospital refused him. James Reeb died shortly after arriving at the Birmingham hospital—no one was ever found guilty in his murder.19, 20

The Criminals

The murderous, hate-filled mobs.

The local cops and officials who led these mobs, looked the other way while they lynched, and never charged anyone for killing Black people.

The state officials who devised and enforced bizarre regulations and laws to prevent Black people from voting, and punished and humiliated them if they tried.

The many congressmen and senators who encouraged and egged on the racist violence, and the others who looked away and never lifted a finger to stop it.

The political leadership of both the Democratic and (since the betrayal of Reconstruction in 1876) Republican parties, including each and every president, who never denounced, much less acted to stop, lynching and routine violations of supposedly basic rights.

The courts and judges, up to the U.S. Supreme Court, who upheld the lynch mobs by ruling, essentially, that it wasn’t their problem, and who refused to enforce the plain language of their own Constitution as Black people were systematically, massively, and violently prevented from voting.

An entire system responsible for the oppression, repression, and denial of fundamental rights of Black people.

The Motives: In Their Own Words

The incidents described above—only a small portion of the attacks to suppress voting rights of Black people over the past 150 years—illustrate the relentless, violent white supremacy that is deeply embedded in every dimension of U.S. society. The packs of hooded racists, the local police and political officials, the senators and Supreme Court officials—all serve a system that thrives on and perpetuates white supremacy.

Ben Tillman, founder of Clemson University, governor of South Carolina, and U.S. senator, in a speech to the U.S. Senate in 1900: “We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.”21

Theodore Bilbo, in his successful run for senator from Mississippi in 1946: “I call on every red-blooded white man to use any means to keep the niggers away from the polls. If you don’t understand what that means you are just plain dumb.”22

Since the 1960s, it has been Republicans working to suppress the votes of Black people—the language they use has been coded (see the words from Republican strategist Lee Atwater at the beginning of this article), but is every bit as vicious and threatening as that of the arch segregationists from America’s earlier times.

Justin Clark, a top official in Trump’s re-election campaign, talking earlier this year about suppressing votes of Black people: “Let’s start protecting our voters. We know where they are…. Let’s start playing offense a little bit. That’s what you’re going to see in 2020. It’s going to be a much bigger program, a much more aggressive program, a much better-funded program.”23 (Emphasis added)

Donald Trump in late March 2020, referring to efforts aimed at removing barriers to voting that disproportionately impact Black and Latino people: “The things they had in there were crazy. They had things, levels of voting that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”24

Repeat Offenders

As protest and upheaval raged across the U.S. in the mid-1960s, and the gross injustices of the brutal oppression of Black people in “the land of the free” were broadcast around the globe, Congress passed and President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It was meant to remove the “Black code” barriers to Black people’s right to vote. Many more Black people did begin to vote, and the number of Black elected officials grew significantly.

See Part 2 of American Crime #11 for assaults on Black people's right to vote since then.

1. Lee Atwater’s Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy, Rick Perlstein, The Nation, 11/13/12. [back]

2. New Orleans Massacre (1866), https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/new-orleans-massacre-1866/ [back]

3. An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866, LSU Press, 2001, by James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. [back]

4. The Eutaw Riot of 1870, Black Then https://blackthen.com/the-eutaw-riot-of-1870/. [back]

5. The 1873 Colfax Massacre Crippled the Reconstruction Era, Danny Lewis, Smithsonian Magazine, 4/13/16. [back]

6. Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, Harper Collins, 2011. [back]

7. The Colfax Massacre of 1873, revcom.us. [back]

8. The Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/hamburg-massacre/. [back]

9. NCpedia, The Wilmington Race Riot. [back]

10. The Ghosts of 1898: Wilmington's Race Riot and the Rise of White Supremacy, Observer Company, 2005, Timothy Tyson. [back]

11. Ocoee on Fire, Florida History. [back]

12. The Ocoee Massacre, The Zinn History Project. [back]

13. Civil Rights Movement History, 1961. [back]

14. Mississippi Encyclopedia, McComb. [back]

15. Canton Civil Rights Movement, Mississippi Encyclopedia. [back]

16. Coming of Age in Mississippi, Doubleday, 1968; Ann Moody. [back]

17. We are Not Afraid, Macmillan, 1988; Seth Cagin, Phil Dray. [back]

18. Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman, Mississippi Freedom Summer Notes. [back]

19. At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-69, Simon & Schuster, 2006, Taylor Branch. [back]

20. SNCC in Alabama, Encyclopedia of Alabama. [back]

21. American Passages, A History of the U.S., Volume 2: Since 1865, Wadsworth, 2004, by Edward L. Ayers, Lewis L. Gould, David M. Oshinsky, Jean R. Soderlund. [back]

22. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy, Bloomsbury, 2018, by Carol Anderson. [back]

23. Trump Advisor Caught Discussing Aggressive Voter Suppression, Rolling Stone. [back]

24. Trump Says Republican Could Never Be Elected Again if Voting Was Easier, The Guardian. [back]