Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.”

3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better:

1) People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.

2) People have to dig seriously and scientifically into how this system of capitalism-imperialism actually works, and what this actually causes in the world.

3) People have to look deeply into the solution to all this.

Bob Avakian

May 1st, 2016

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

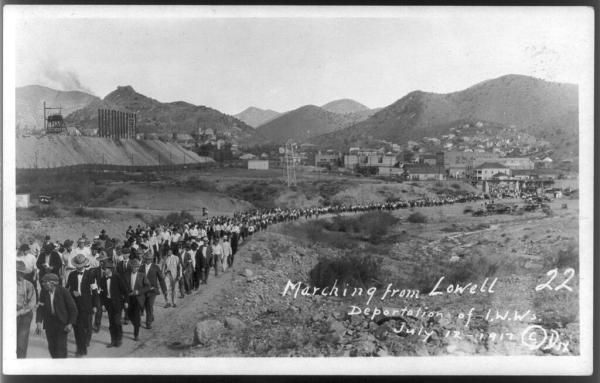

Miners on strike marching from Lowell, Arizona, July 12, 1917. Photo: PD

The Crime

In early 1917, the U.S. officially entered World War 1 against Germany. The war effort led to a big increase in the demand for copper, a mineral crucial in manufacturing military hardware. Major copper mines were located in Arizona and other western states. During this time, there were strikes at these mines, some of them led by the International Workers of the World (IWW).

In early July, IWW workers at the Copper Queen Mine in Bisbee, Arizona (11 miles from the Mexican border) went on strike against the owners, the Phelps Dodge Mining Company, one of the largest mining companies in New Mexico and Arizona.

The IWW was a radical union that was founded in 1905. The Preamble to the Constitution of the IWW stated: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.”1

On July 12, in an effort to smash the strike and the union, Bisbee’s Sheriff, Henry Wheeler, organized a force of 2,000 vigilantes. In a planned and organized action, the vigilantes rounded up 2,000 striking miners and others. The vigilantes force-marched the miners two miles to the local baseball field, loaded 1,186 of them in box cars without food and water, and sent them off to be unloaded in the desert at Hermanas, New Mexico. This was the Bisbee Deportation of 1917.

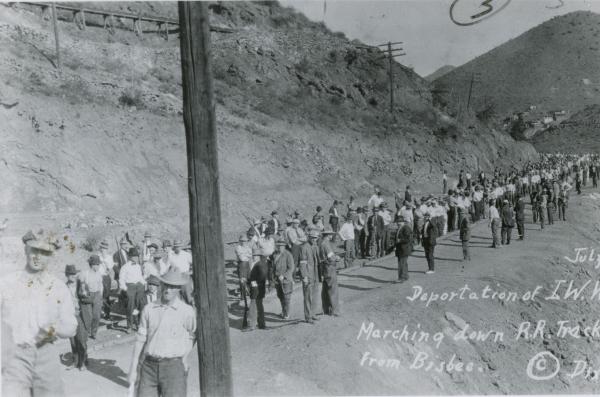

In Bisbee, Arizona, the deportation of IWW workers from mining site, July 1917. Photo: PD Arizona Historical Society

At 6:30 am, Sheriff Wheeler called for “martial law,” and torrents of armed vigilantes flooded the streets and alleys of Bisbee. The vigilantes formed goon squads and went through rooming houses, private homes and the union hall. They dragged half-naked men out of the boarding houses and went into barbershops and restaurants to get people.

One-third of those rounded up were Mexicans, who were the strongest supporters of the strike. Less than 20 percent of the deportees were U.S. citizens. The rest were made up of 33 different nationalities, with immigrants from Finland, Serbia, Ireland and Austria as the largest groupings.

Once the deportees had reached the baseball field, they were loaded onto railroad boxcars as hundreds of vigilantes stood guard. At 1:00 pm, the train left Bisbee heading east.

Fred Watson, a deportee said: “In the boxcar I was in, there was nothing but sheep dung. Whether there was any bread and water in the others, I don’t know... The boxcar I was in had nothing and I never saw any sandwiches. The first thing I ate was a piece of hardtack and a drink of water, and I vomited it right back.”2

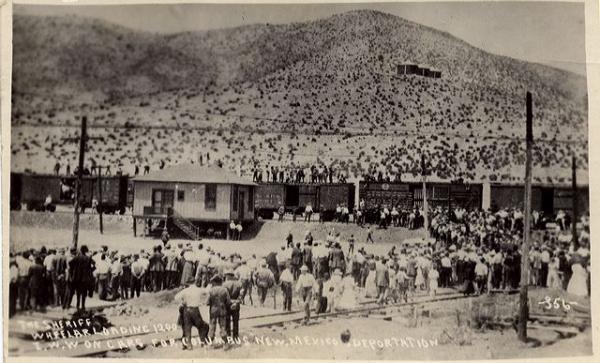

The Sheriff loading 1200 I.W.W. workers on rail cars for deportation from Bisbee, Arizona, July 1917. Photo: PD

The deportees were dropped off in the New Mexico desert with the temperature around 90 degrees. Two days later, the men were relocated to Columbus, New Mexico, where they self-organized, continuing to vow that they would all return together to Bisbee. Their sole demand: “They want their liberty and their right to support themselves and their families, but they want that liberty to be restored to them where it was taken from them.”3

After two months in Columbus, the U.S. Army tore down the deportees’ tents and cut their food rations. The deportees were forced to leave Columbus. Some found new jobs, although many were blacklisted. But they could never return to Bisbee. Bisbee was turned into a fortress to keep any unwanted people from entering. Vigilantes patrolled the neighborhoods. People understood that if you helped anyone against the wishes of the authorities, you’d be next. Families were broken, the community was shattered. In particular, the Mexican families left behind came under the greatest hardship. As one account reported, the Mexican residents were “destitute (and) further, no aid was being given to them…”4

After the deportation, the ethnic cleansing of Bisbee (of the Mexicans and the IWW) became central to the life of the town. The Bisbee Daily Review wrote, “Just because Bisbee arose in her might and drove some twelve hundred red flaggers out of the district is no sign that her work is done. Our real task is yet to do, WE MUST KEEP THEM OUT!”5

On July 21, an order was issued to arrest for vagrancy all unemployed men in Bisbee who did not have previous clearance. That morning Sheriff Wheeler began the roundup of the unemployed.6 Months after the deportation, men were still being rounded up for “vagrancy” and sentenced to 90 days in jail or given two days to leave town.7

Kangaroo courts were formed for those returning or going to Bisbee—anyone who came back from Columbus was thrown in jail. They were brought before those courts and given a certain length of time to sell whatever they owned and leave town.8

A year later, the federal government indicted Wheeler and 21 vigilantes for violating the civil rights of those they deported. But the U.S. Supreme Court, in an 8-1 decision, ruled that the U.S. government did not have the power to intervene. When the 21 and Wheeler came to trial in state court, they claimed that they had the legal right to deport the miners based on the “law of necessity”9—saying they were justified in their vigilante actions because that was necessary to prevent a larger crime. They were found not guilty. The County Attorney, Robert French, dismissed all charges made against 123 vigilantes and the Phelps Dodge Company. The state of Arizona refused to prosecute anyone else. No one went to jail for kidnapping 2,000 people.

The Criminals

Sheriff Henry Wheeler: He organized the Workman’s Loyalty League, through which he supposedly “deputized”10 the anti-IWW workers. These and others were the vigilantes who carried out the Bisbee deportation. Wheeler stated: “I have formed a sheriff’s posse of 1200 men in Bisbee and 1000 men in Douglas, all loyal Americans, for the purpose of arresting on the charges of vagrancy and treason, and of being disturbers of the peace of Cochise County…”11 Wheeler vowed to make Bisbee “an American camp where American men may enjoy life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness unmolested by alien enemies of what ever breed.”12

The Sheriff loading 1200 I.W.W. workers on rail cars for deportation from Bisbee, Arizona, July 1917. Photo: PD

The Vigilantes: The vigilantes were comprised of the Loyalty League, Citizens Protective League, Business Men’s Protection Association, and employees of Phelps Dodge Company. The Citizen’s Protective League called the strike “treason to our government.”13

Phelps Dodge Company: Phelps Dodge President Walter Douglas called the strike a “foreign led conspiracy.”14 Phelps Dodge provided the vigilantes with many of the guns they used during the deportation.15 Douglas issued the orders for the actual deportation by railroad.16

Arizona Governor Thomas Campbell: Campbell stated that the principles of the IWW “are a stench in the mouths of decent Americans” and “a menace to civic well-being and industrial progress in the time of peace… Such doctrines during a time of war is treason.”17 Campbell actively supported the arming of the vigilantes and the role that the Loyalty League and others would play in the deportation.18

Bisbee Daily Review: The paper actively supported the mass deportation of strikers. They wrote things like: “The policies of peace had failed. The Mexicans were beginning to parade by the hundred. The ‘wobblies’ [IWW] were beginning to show their teeth. Their dupes were beginning to get hungry. And the citizens, who were watching every move of their enemy, every mood, every turn, every ripple, KNEW THAT THEY MUST STRIKE QUICKLY AND HARD.”19

The Alibi

The mine owners and those who opposed the striking workers claimed that the IWW was basically a “German front” organization, funded with German money. Those who opposed the IWW called the union a seditious organization that endangered the U.S. war effort and threatened the social order.20

The Bisbee strike became a national issue when Colorado Senator Charles Thomas charged that the IWW was working with German agents “to cripple smelters and industry in the west,” particularly the mines in Arizona.21

The Real Motive

World War 1 started in 1914 and lasted until 1918. This was a war in which two blocs of imperialist great powers fought each other. One bloc included Great Britain, France, and the U.S. (and Russia was part of this alliance); and the other was led by Germany with its allies. They were fighting for global supremacy, particularly control over the oppressed colonial regions of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

World War 1 created an enormous demand for copper, with Arizona producing 17 percent of the nation’s copper. Prices soared and profits exploded, but the miners’ wages stayed flat. Any effort to halt that production was seen to hinder the war effort.

The IWW opposed the war. They called it “the capitalist war” and their position was to condemn all wars.22 The IWW was particularly successful recruiting Bisbee's Mexican workers.23

During World War 1, revolution was in the air in many parts of the world. This was true in Mexico, where the Mexican revolution was continuing. Mexican copper miners in Sonora, Mexico, near the Arizona border, waged a number of strikes and joined the revolutionary army in large numbers.24 As part of the Mexican revolution, in 1916 Pancho Villa led an incursion into Columbus, New Mexico. Prior to that, he and his men threatened to seize the town of Douglas, Arizona, where Phelps Dodge had a mine. All of this was reported in the Bisbee press. This spread fear in the area that the Mexicans coming to work in Bisbee mines were armed “Villistas.”25 (To understand more about the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico at this time see "An Imperialist Parasitic Harvest: Savagely Exploitative and Entrenched, A contribution on the Historical Roots of the U.S. Domination of Mexico," by Juan Rojo.)

Phelps Dodge’s owners saw a strike in their mines during wartime as treason or sabotage. In the name of “national security,” they rejected the union’s demands, and the strike began. For the company and other powerful forces, America could not have its copper production disrupted—so, the strike had to be crushed.

On July 6, a town meeting of 500 Bisbee residents passed resolutions “declaring the IWW to be a public enemy of the United States.”26 Plans were then made for the deportation.27 On July 11, Sheriff Wheeler called a meeting of 2,000 vigilantes to crush the strike and told them, “This is no labor trouble but a direct attempt to embarrass the government.” The stage was set for the mass deportation.

During the investigation into the deportation in the aftermath, Arizona Governor George Hunt, who had replaced Campbell as the governor, told President Woodrow Wilson that “There was not to be found the slightest evidence of German money…” and that the claim of German influence in the IWW was “a hoax pure and simple.”28

The Bisbee deportation had a major effect on other labor disputes throughout the country during the war years, and laws were enacted that made it illegal to advocate views and opinions that differed from or opposed the government.

Fred Watson, a deportee, said many years later, “HOW IT COULD HAVE HAPPENED in a civilized country I’ll never know. This is the only country it could have happened in. As far as we’re concerned, we’re still on strike!...” When his wife said that was 60 years ago and he should forget about it, Watson said, “I’ll forget it when I die! I’ll forget it when I die!”29