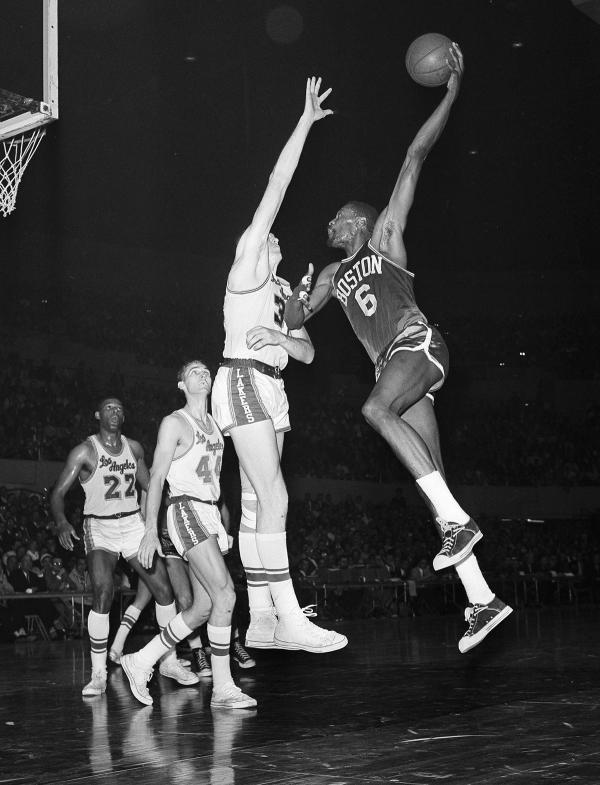

In the history of sports you can count on your fingers and toes the number of great athletes who also acted in the interests of humanity—Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Colin Kaepernick, Martina Navratilova, Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bruce Lee, Althea Gibson, Craig Hodges, Billie Jean King. Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, Megan Rapinoe, Paul Robeson, and Bill Walton are some. Bill Russell stands out as one of those.

Bill Russell’s struggle against racism was shaped by his experiences growing up and playing basketball. He was born in Louisiana, where he first encountered and was told about how Black people were treated by his grandfather and father—both who refused to back down when confronted with racism. In an article for Slam magazine’s social justice issue, Russell wrote, “What I learned from these events and the many other events that I saw or experienced like them was twofold: First, that you must make the price of injustice too high to pay, and second, that such events are not reflective of your character, but of the character of the perpetrator.”1

His family moved to Oakland, California, when he was nine years old. They lived in the projects in west Oakland. It was a tough segregated neighborhood, and Russell found himself in many fights growing up there. As he recalled later, his mother told him “that it didn’t matter whether I won or lost those fights, but what mattered was that I stood up for myself.”2

He attended McClymonds High School, which had an overwhelmingly Black student body. Surprisingly, he was not a great basketball player in high school and only made the varsity in his senior year. His experiences as a youth and young man shaped his determination to fight against racism and to become a great basketball player, to struggle with determination to break through and overcome some of the barriers that held Black people back.

Facing and Fighting Against Racism in College and the NBA

The racism that Russell faced followed him to college and then to the NBA. Russell’s college, the University of San Francisco (USF), was the first major university in the nation with three starting Black players. In 1954, the team went to Oklahoma City for a tournament, and the players were not allowed into the team hotel due to the presence of Black players.3 Despite being the best basketball player in America in his final year in college, he was not awarded Player of the Year in Northern California.4 That award went to a white player.

Russell’s daughter recounted that when her father played for the NBA's Boston Celtics, “the fans called him 'chocolate boy,’ ‘coon,’ ‘nigger,’ you name it…”5 Their house in Boston had been burglarized. “Our house was in a shambles, and ''NIGGA'' was spray-painted on the walls. The burglars had poured beer on the pool table and ripped up the felt. They had broken into my father's trophy case and smashed most of the trophies.” Russell always claimed that he played for “the Celtics, period. I did not play for Boston,” and he referred to the city as “a flea market of racism.”6

Russell’s encounter with racism also came at the hands of the cops. After George Floyd was murdered by the cops, Russell wrote about his experiences:

When I was a kid, I learned to run away from the police because they’d arrest you, or kick you, or kill you if you were Black… As an adult, the police would follow me around Boston, Reading, Mercer Island, Los Angeles… You don’t need me to tell you that racist police officers are a problem, and you don’t need me to tell you that such racism is pervasive throughout not just police departments, but every American institution because every American institution was built on the backs of Black and Brown people.7

After receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Russell tweeted out a picture of himself wearing the medal and down on one knee, emulating NFL player Colin Kaepernick who took a knee during the national anthem to protest police murders of Black people. Russell tweeted, “Proud to take a knee and stand tall against social injustice.”

After receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Russell tweeted out a picture of himself wearing the medal and down on one knee @RealBillRussell

As a player for the Celtics, he led a boycott of an unprecedented exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky, when a restaurant would not seat Russell and his Black teammates. He helped to lead an integrated basketball camp in Jackson, Mississippi, after Medgar Evers was assassinated there in 1963.

As a basketball player, Russell changed the game, especially the way that defense is played. The NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) made a rule change based on how Russell played.

The college conference Russell played in also adopted the “Russell Rule,” which “requires each member institution to include a member of a traditionally underrepresented community in the pool of final candidates for every athletic director, senior administrator, head coach and full-time assistant coach position in the athletic department.”8

But it is his determination to fight against racism that makes Bill Russell a very special person.

The NBA’s all-time leading scorer, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, knew Bill Russell for a long time. Together, they were part of the Cleveland Summit, where a small group of prominent athletes gathered to support Muhammad Ali’s decision not to go and fight in Vietnam. In his recent piece in the Atlantic, The Bill Russell I Knew for 60 Years, Kareem writes, “The Bill Russell of the Cleveland Summit was who I wanted to be when I grew up. In fact, the Bill Russell of the Cleveland Summit made me grow up right then and there. As I had emulated him on the court, I chose to also emulate him off the court.”

Russell told his daughter, “I knew you'd encounter racism and sexism, and maybe, in some ways, that's a good thing. If you were too sheltered, I'm afraid you'd be too naive. If you were too sheltered, you might not be motivated to help others who do not have your advantages.''9

“He stood for humanity, activism and equality”

Former NBA player Etan Thomas interviewed three activist athletes in an article published in Basketball News online, “Dr. John Carlos, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, Craig Hodges remember Bill Russell.” Carlos, who gave the Black Power salute on the victory stand during the national anthem at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, said, “...Bill Russell was the blueprint for the modern-day athlete. He stood for humanity, activism and equality. But he didn’t just talk the talk, he walked the walk for the better part of his life.... I remember being introduced to Bill Russell by my buddy, Blaine Robinson, and the first thing he said was... [Russell] looked at me and smiled and said, 'Carlos, I got one bone to pick with you,' and I said, 'What’s that Bill?' and he said, 'You thought to do that shit in Mexico before I did.'”

Abdul-Rauf, who played for the NBA Denver Nuggets and refused to stand for the national anthem, said, “[Russell] lent his support to others and it extended beyond the labels that society placed on its citizens in an effort to draw the lines in the sand, so to speak. For example, take his support for Muhammad Ali; [Bill] wasn’t a Muslim, but he saw that it was an injustice and he lent his support and that’s what made him special. Bill Russell was a free thinker. He is definitely going to be missed, and a gap has been created. Anytime you lose a figure like that in the world, with that type of impact, a gap has been created, and it’s hard to fill."

Hodges, who played for the NBA Chicago Bulls, and tried to organize an NBA finals game boycott after the Rodney King beating, said, “When I think about where I sit as far as social activism, to me, it’s like a kaleidoscope when you look back at the history of athletes using their voices. It’s like a kaleidoscope when I think of the '68 Olympic experience, Muhammad Ali, and his fights, and Bill Russell and what he was doing in Boston. It was all connected, and that’s the beauty of what it was.”

In an article for the Boston Globe, Bill Russell wrote, “[There’s] the kind of strange that means peculiar, perverse, uncomfortable and ill at ease. Now that’s the kind of strange I’ve known my whole life. It’s the kind of strange Billie Holiday sang about when she sang, ‘Southern trees bear a strange fruit. Blood on the leaves and blood on the root,’ referring of course, to the then common practice of the lynching of Black people.”10

Russell’s legacy is much more than what he did on the court. His legacy is to end all the “strange” that Black people face—police brutality, mass incarceration, all forms of discrimination, and white supremacy.