In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed on the western part of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola—known as Ayiti (Haiti) by its natives—and claimed it for the Spanish empire.

Map: gisgeography.com

Thus began Haiti’s descent into hell. Spanish colonists enslaved the native Taino Arawak people to mine gold. “Within 50 years, some half a million Arawaks had been exterminated,”1 and all the gold was gone. The Spanish moved on to spread their murderous rule over most of South and Central America.

Gradually, French colonists began to settle, and in 1696 Spain ceded control of the western part of the island to France. (The east—what is now the Dominican Republic—remained in Spanish hands.) This opened the way to 100 years of vicious French rule.

France “imported” hundreds of thousands of abducted-and-enslaved Africans to toil—and die—under Haiti’s tropical sun. They worked 12 hours a day, six days a week, on coffee and sugar plantations, naked or dressed in rags. Cruel overseers whipped men and women, children and old people alike if they slacked off.

For enslaved people, resistance or flight was met with truly unspeakable tortures.In this illustration, blood hounds attack a black family in the woods, circa 1800. Illustration from Marcus Rainsford, An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti. Londres J. Cundee, 1805. Coll. New York Public Library.

Resistance or flight was met with truly unspeakable tortures. As the New York Times has recounted, slaves were “kept in line by hunger, exhaustion and public acts of extreme violence. Crowds of colonists gathered in one of the island’s fancy squares to watch them be burned alive or broken, bone by bone, on a wheel. Sadistic punishments were so common they were given names like the ‘four post’ or the ‘ladder,’ historians note. There was even a technique of stuffing enslaved people with gunpowder to blow them up like cannonballs, described as burning ‘a little powder in the arse,’ according to French historian Pierre de Vaissière.”2

Charged with torturing two female slaves to death, a slaveowner did not deny it, but “justified” his barbarous crime, writing that the only thing that keeps “the slave from stabbing the master” is “the absolute power he has over him.” The court acquitted him.3

The blood and sweat shed by slaves produced massive wealth for the slaveowners in Haiti and for France. Haiti was the most profitable colony in the world, the world’s largest producer of sugar and a major producer of coffee.4 This wealth not only fed the appetite for luxury of Haitian slaveowners and the ruling aristocratic class in France, but provided much of the foundation for the birth and growth of French capitalism which was emerging at that time and took power through the French Revolution (1789-1799).5

The World’s First Successful Slave Rebellion

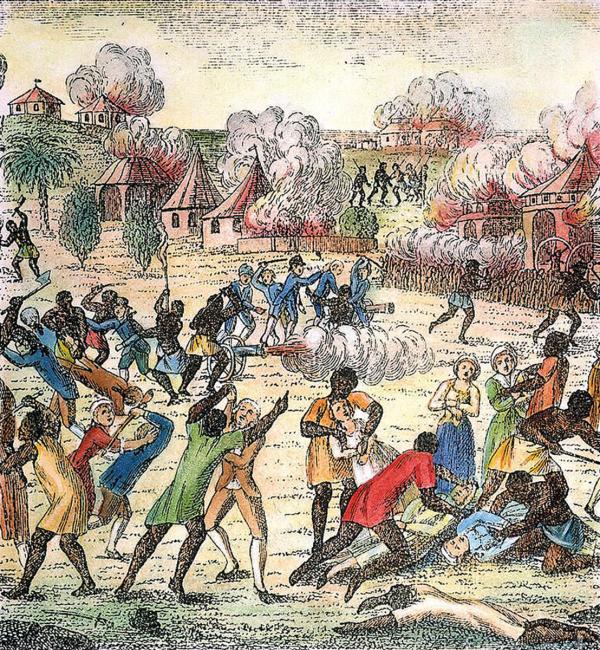

Engraving of Haitian slave revolt, 1791-1804.

In 1791, a massive slave rebellion began, starting with slaves armed with primitive weapons. Using what they had, they seized and burned the hated plantations, and defeated the armed forces of the slaveowners. Then Britain and Spain—colonial powers that saw the slave rebellion as a chance for them to edge out France and enslave Haiti themselves—sent armies to Haiti; the revolutionary slaves defeated both. Finally, the most famous French general and leader, Napoleon, sent an army of at least 23,000 experienced troops, fresh from conquering much of Europe. They too were defeated by the slaves. On January 1, 1804, Haiti declared its independence and abolished slavery, marking the first successful slave revolution in history.

1803, the self-liberated slaves of Haiti defeated Napoleon's army at the Battle of Vertières, marking their final victory over French colonialism. Illustration: Wiki Creative Commons

This was—and remains—an inspiring achievement. But what was the situation that the newly free slaves confronted? Their own country had been ravaged by 12 years of war. As much as one-third of the black population had died in the war. Almost all the basic infrastructure—plantations, irrigation systems, buildings, tools—was destroyed and needed to be rebuilt.

At that point in human history, there was no way to organize an economy other than one or another form of exploitation—slavery, feudalism or capitalism.6 But in reality, even the option of developing as an independent capitalist country was closed off. Haiti was not born into a world of freely developing countries, but one already divided into oppressed and oppressor nations. It was a world dominated by European colonialism, which would soon develop into capitalism-imperialism.

The colonial powers hated and feared what Haiti represented—the potential for oppressed and enslaved people that their power and wealth was built on rising up against them.7 At the same time, all these powers were eying Haiti like a juicy piece of meat that they wanted to incorporate (or in the case of France, re-incorporate) into their empires.

So for the most part, they joined French efforts to isolate and weaken Haiti. No country even recognized Haiti until 1815, and the U.S. did not recognize it until 1862—58 years after independence! This had a real impact on Haiti, limiting international trade that was necessary for reconstruction.

All this made Haiti’s overall situation extremely fragile. Under these conditions, the threat of foreign invasion, reconquest and re-enslavement was very real. Because of that, most of Haiti’s already limited resources were funneled into military defense, including a network of 30 ocean-facing fortresses that took 10 years and tens of thousands of people to build.

French Imperialist Domination: Debt, a New Form of Enslavement

Then in 1825, 14 French warships sailed into Haiti’s waters. Their commander made a demand: Haiti must pay 150 million francs, as “reparations”8 for France’s lost “property”—that is, the slaves! In return, France said it would recognize Haiti and open up wider trade (with conditions making that trade more favorable to France than to other countries).

Faced with the prospect of another war with a major power, and the promise of peace and desperately needed international trade, Haiti’s rulers agreed to pay the “debt” France claimed they “owed.”

The sum of 150 million francs was a huge amount of money—almost twice as much as France charged the U.S. to buy the Louisiana Territory, which is 77 times as big as Haiti. It was broken up into five installments, but even the first installment of 24 million francs was far beyond Haiti’s means. In 1831, Haitian leaders told France they could not pay on schedule. France threatened to invade with 500,000 troops!

Then France “generously” hooked Haiti up with a private French bank, which loaned Haiti 30 million francs… but charged a fee of six million! Now Haiti was deeply in debt to France, and to private banks.

So this wasn’t just a one-time massive robbery; it was a way of locking Haiti into an endless cycle of debt on top of debt, with payment enforced by the threat of war. Payment of this debt continued and mushroomed well into the 20th century; in some years totaling 40 percent of Haiti’s government revenues. Between 1825 and 1957, international debt on average took almost one-fifth of the Haiti’s annual revenue!9

Think about the implications of this. First of all, it meant there was little or no money for the functions that even oppressive governments normally perform. No money for public schools—even in our time (as of 2010) there are 14,424 private schools compared to only 1,240 public ones, and almost 40 percent of the people are illiterate. No money for roads to connect the different parts of the country and connect the rural areas to the cities—still today vast stretches of the countryside are reachable only on foot, mule or horseback.

And on and on: no money for irrigation systems, for forestation and forest management, for flood control. No money for hospitals. No money for electric grids or water systems. All of these crippling problems persist to this very day.

People, and a pig, search for food and other items in piles of garbage by the sea in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, July 9, 2003. Photo: AP

The debt also gave the French (and as time went on, the U.S, which became a major “lender” to Haiti in the late 1800s) leverage to interfere in Haiti politically. French and U.S. warships often “visited” Haitian ports, looking after their “investment.” Increasingly, rival imperialists would back different political parties and armed groups (known as Cacos) connected to these parties as a way of consolidating their own control. This amped up chronic political instability and factional warfare. Between 1843 and 1915, Haiti had 22 different governments. Then the imperialists turned around and pointed to this “instability”—that they were fueling—as “proof” that “Black people can’t rule themselves.” In 1915, “ensuring payment on the debt” was one of the justifications the U.S. used to invade Haiti and occupy it for 19 years!

With the imperialist governments and banks constantly breathing down their necks, to a large extent the Haitian government became a “pumping station”—sweeping up anything the masses had beyond survival needs through exorbitant taxes, customs charges and other means, and then funneling it into the coffers of imperialism (in addition to a portion that went to political leaders and the Haitian ruling class).

And this in turn has political consequences. On the one hand, this new form of enslavement requires—like the old slave system—a high level of repression of the masses of people who are being robbed blind. And on the other hand, it breeds corruption in the government, including among low-level employees whose salaries have to be “supplemented” by bribes in order to support their families. And at the top levels, government power is all about how much you can skim off from these massive transfers of national wealth.10

So to sum up, Haiti’s fundamental problem is the fact that for 200 years it has been ensnared in a web of imperialist oppression, and this has distorted the whole society—the economy, the educational system, the government, etc.—to fit the needs of imperialism. This is why we say again, nothing short of a deepgoing REAL revolution, guided by the new communism developed by Bob Avakian, BA, can unleash and lead the masses to uproot this old order, root and branch, replace it with a system based on the needs of people in Haiti and of humanity as a whole, and defend this new society from its enemies inside and outside of Haiti.

Our next article will look at the century-plus of U.S. domination of Haiti.