Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has “to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.”

3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better:

1) People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this.

2) People have to dig seriously and scientifically into how this system of capitalism-imperialism actually works, and what this actually causes in the world.

3) People have to look deeply into the solution to all this.

Bob Avakian

May 1st, 2016

In that light, and in that spirit, “American Crime” is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment focuses on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

See all the articles in this series.

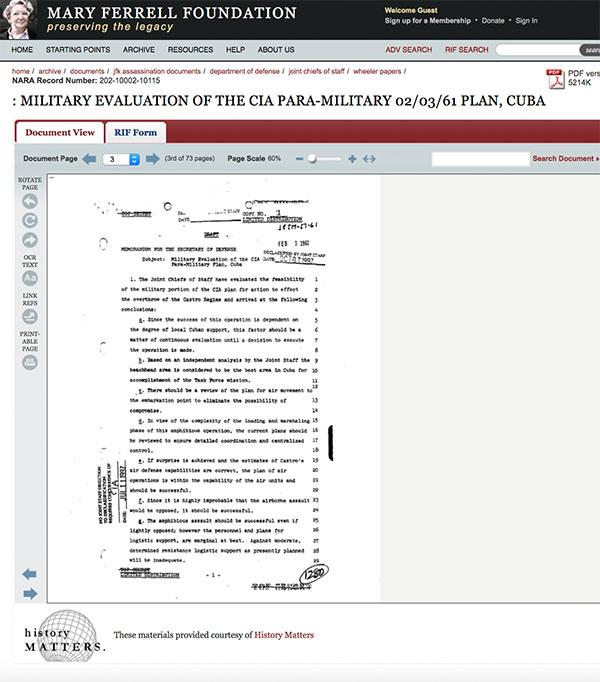

U.S. B-26 plane shot down by Cuban forces during the mercenary Bay of Pigs invasion.

B-26 of mercenary shot down.

THE CRIME:

On April 15, 1961, a mercenary army of Cuban counter-revolutionary exiles (often referred to as “gusanos,” “worms” in Spanish) launched an attack on Cuba with the intent of overthrowing the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. They were organized, armed, and led by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The operation’s first phase was a surprise attack on Cuban airports by CIA-trained pilots. The goal of this aerial attack was to destroy Cuba’s small air force as a prelude to a sea invasion by 1,300 CIA-trained Cuban mercenaries. It destroyed about half of Cuba’s planes, but not all, a fact that became important in the days that followed.

After the attack, a flotilla of chartered commercial freighters, carrying the 1,300 soldiers of “Brigade 2506,” left a port city in Nicaragua and made its way toward the coast of Cuba—escorted by a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier and five destroyers.

The invasion plan, written by top brass of the CIA and approved by the U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, the U.S. military Joint Chiefs of Staff and President John Kennedy, called for the heavily armed mercenaries to establish a beachhead in the relatively remote coastal area around La Bahia de Cochinos, the Bay of Pigs.

Once established with the help of CIA supplied air cover, the three landing groups would link up. The U.S. Navy would supply them with heavy equipment, including battle tanks and earth-moving equipment. Then a “Cuban Revolutionary Council” would be flown from Florida to the Bay of Pigs and recognized by the U.S. government as Cuba’s new, legitimate rulers. This would, according to the CIA, give the U.S. the legal right to intervene directly.

The plan began to unravel even before the first invaders reached shore. The landing groups were thrown off by coral reefs that rimmed the shore around the Bay of Pigs and other unexpected obstacles. The CIA expected the invasion to set off protests or uprisings against the Cuban government. Instead, in the days following the invasion, Cubans came out in large, angry demonstrations against U.S. imperialist aggression and in support of the Castro government. Tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers and militia set out to confront the invaders, which included mercenary paratroopers dropped to block roads to the landing beaches. Armed clashes took place on these roads with the mercenaries using terror weapons like phosphorous shells and air-dropped napalm. But these CIA mercenaries were overwhelmed by the Cuban army and militia. Meanwhile, pilots of the few planes left in the Cuban air force were able to destroy two of the chartered freighters loaded with ammunition and other supplies. Fearing a similar fate, other freighters fled the scene, leaving the CIA army stranded with little food and dwindling supplies of ammunition.

Angry demonstrations erupted around the world at U.S. embassies protesting this naked aggression against Cuba. The Kennedy administration realized the invasion was turning into a bloody and politically damaging debacle, and prohibited direct U.S. military involvement in the fighting.

Some 2,000 to 6,000 Cuban soldiers, militia personnel and others were killed, wounded or went missing in the first days of this U.S. organized assault. But by the evening of April 18, barely three days after they landed, the CIA’s invading force was falling apart. Soldiers of the mercenary Brigade 2506 tried to escape the beaches, and when that failed they surrendered to the Cuban revolutionary army and militia and were taken prisoners.

BAsics from the talks and writings of Bob Avakian

Here I want to bring up a formulation that I love, because it captures so much that is essential. Soon after September 11, someone said, or wrote somewhere, that living in the U.S. is a little bit like living in the house of Tony Soprano. You know, or you have a sense, that all the goodies that you’ve gotten have something to do with what the master of the house is doing out there in the world. Yet you don’t want to look too deeply or too far at what that might be, because it might upset everything—not only what you have, all your possessions, but all the assumptions on which you base your life.

—Bob Avakian, BAsics 5:10

THE CRIMINALS:

President Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1960): Approved plan, written by the CIA and presented to him on March 17, 1960, to overthrow the Cuban government and assassinate its top political leadership, titled “A Program of Covert Action Against the Castro Regime.”

President John Kennedy (1961-63): After assuming the presidency, Kennedy approved the CIA Bay of Pigs invasion plan. His biggest concern was that the U.S. hand in the operation be hidden as much as possible from public view and that it would allow his government “plausible deniability.” After the invasion fell apart, Kennedy, and his brother Robert, initiated Operation Mongoose, a sustained effort to assassinate Fidel Castro.

Allen Dulles, director of the CIA (1952 to November 1961). After overseeing the 1953 U.S. coup against the Mosaddegh government in Iran and the 1954 coup against the Árbenz Guzmán government in Guatemala, Dulles helped plan the Bay of Pigs invasion. He assumed the U.S. could not fail.

Richard Bissell: Bissell, a former professor of economics at Yale University, was put in charge of planning the Bay of Pigs invasion. Bissell chose veterans of the Guatemala coup to help with the Bay of Pigs. CIA radio broadcasts and anti-Castro newspapers and leaflets were part of the psychological and political preparation. Bissell believed the Cuban government would collapse under psychological stress of the invasion. He later wanted to enlist the Mafia to assassinate Fidel Castro, keeping the CIA’s hands “clean.”

U.S. military Joint Chiefs of Staff: The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the Bay of Pigs operation. They supplied logistical support and weapons, including tanks, jeeps and trucks. A U.S. Navy ship supplied landing craft for the invasion and others were on hand to support the operation if necessary.

Cuban counter-revolutionary exiles (“gusanos”): These exiles, who fled Cuba after the 1959 revolution, were heavily recruited by the CIA for its invasion force. They included all manner of thugs and reactionaries: former military, police and political officials from the brutal, pro-U.S. Batista regime. They also included businessmen, officials of U.S.-owned companies, gangsters and other exploiters from the old regime, who aimed to recoup their lost fortunes and restore the U.S. stranglehold on Cuba.

THE ALIBI:

The U.S. claimed the Bay of Pigs invasion was the work of disaffected Cubans, who represented the feelings and aspirations of millions of Cubans, and made elaborate efforts to make the invasion look that way—with no U.S. involvement. For instance, the CIA trained its Cuban brigade on a remote base in Guatemala. The initial CIA air assault on Cuba’s Air Force was carried out using World War 2 vintage B-26 bombers like those used by the Cuban Air Force, with Cuban air force markings on their fuselages. When the bombing began, one pilot flew his B-26 to Miami and asked for asylum. He claimed to be part of a Cuban rebellion against Castro’s “communist” policies. U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson displayed pictures of this CIA fabrication later that day at the UN General Assembly in an attempt to prove the U.S. wasn’t involved.

Three days before the attack, President Kennedy told the media, “This government will do everything it possibly can . . . to make sure that there are no Americans involved in any actions inside Cuba.” Kennedy was worried that the U.S.’s hand would be exposed, but, if that happened, he could still say that no U.S. military personnel were involved. That was also a lie. Two CIA agents joined the invasion and crews of four of the six B-26s that flew air cover for the invaders were members of the Alabama Air National Guard recruited by the CIA.

THE REAL MOTIVE:

On January 1, 1959, a victorious army of rebels under the leadership of Fidel Castro rode into Havana, Cuba and declared the beginning of a new government. It was the culmination of a guerrilla war begun two years before against the regime of Fulgencio Batista, the latest in a long string of brutal, corrupt, pro-U.S. Cuban rulers.

The U.S. at first believed the Castro government would do as other regimes had done throughout the 60 years the U.S. dominated the island—capitulate in the face of its political, economic and military strength. Castro also sought to maintain normal relations with the U.S., but while he was not a revolutionary communist, his program of economic and political reforms alienated the U.S. These included increasing the wages of plantation workers and confiscation of land monopolized by U.S. owners, which were opposed by U.S. business interests. These moves, as well as the example of a successful revolution against a pro-U.S. regime, clashed with the U.S.’s strategic interests in the region. By late 1959 a consensus emerged among U.S. imperialists that the Castro regime had to be destroyed.

At that time the U.S. was the dominant power in the world but the Soviet Union, formerly a revolutionary socialist country, was a newly emerging capitalist-imperialist power beginning to challenge the U.S. all over the world. The Soviet Union used its reputation as a former socialist country, together with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist rhetoric to mask its real goals. With the growing hostility and threats to Cuba from the U.S., the Cuban government turned to the Soviet Union for help, increasing U.S. hostility. Such were the motivations and necessities behind the U.S.’s catastrophically unsuccessful, and thoroughly bloodthirsty, “Bay of Pigs” invasion.

ABOUT THE BOOK, ORDER HERE

See excerpts HERE

Updated pre-publication PDF of this major work—now including the appendices—available HERE

Insight Press has announced that in addition to the print book, THE NEW COMMUNISM is now available as an eBook at Amazon, iBooks, Barnes and Noble and other retail and library websites.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bay_of_Pigs_Invasion

Bay of Pigs Declassified, edited by Peter Kornbluh, The New Press, 1998

Brilliant Disaster: JFK, Castro and America’s Doomed Invasion of Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, Jim Rasenberger, Scribner, 2011

Playa Girón: Bay of Pigs: Washington's First Military Defeat in the Americas, by Fidel Castro and José Ramón Fernández, Pathfinder 2001